An abridged ‘digest’ version of this exclusive investigation is published by Byline Media.

A US hedge-fund with ties to President Donald Trump. Russian banks backed by the Kremlin. Gazprom. A gas pipeline route that threatens Russian energy dominance over Europe. Croatia’s largest company. Jeff Sessions. Interpol. And Trump’s former attorney Michael Cohen.

Unwittingly or otherwise, these are all key players in a rapidly intensifying competition to dominate Europe’s energy supplies.

Energy is a weapon. For both the US and Russia, the prize for wielding this weapon is political and economic leverage over Europe. But new evidence suggests that far from opposing Russia’s European energy hegemony, key figures tied to Trump are complicit in a colossal betrayal: the facilitation of Russia’s stealth gas conquest of Europe. Yet the key to unearthing how Trump’s collusion with Russia has undermined US and European energy security can be found not in Washington or even in Moscow — but within a murky nexus of power in the Balkan state of Croatia.

By late 2016, Christopher Steele, former head of MI6’s Russia desk, had finished compiling his intelligence report purporting to contain evidence of collusion between the Trump presidential campaign and senior Russian officials.

Among the allegations made in the document was that in return for helping Donald Trump win his election campaign, Trump would be expected to make a range of concessions to Russian interests, including an agreement “to raise US/NATO defence commitments in the Baltics and Eastern Europe to deflect attention away from Ukraine, a priority for Putin who needed to cauterise the subject.”

The document also claimed that Trump’s former foreign affairs advisor, Carter Page, had met with a senior Rosneft official in June 2016, who had pressed him on “issues of future bilateral energy cooperation” between the US and Russia.

In broader terms, the dossier alleged that Trump might play a double-game in the Balkans, the outcome of which would favour Putin on energy. At first glance this may not seem obvious. Trump has made loud noises opposing Russia’s Nord Stream 2 — a pipeline connecting with Germany widely criticised for its potential to cement the European Union’s dependence on Russia.

While those noises have had little tangible effect, senior members of Trump’s inner circle have consistently found themselves working with companies that are intensifying Russia’s energy stranglehold on Europe — a collusion ironically enabled by the increasingly fraught sinews of the capitalist ‘globalism’ that Trump pretends to oppose.

At the centre of these machinations is the tiny country of Croatia, which has fast become a central pivot in a new Great Game. As Croatia has moved into the orbit of American and European power, Russia has ramped up efforts to pull it away — primarily using the carrots of cheap money and cheap gas.

The country entered NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme in 2000, before fully joining the alliance in 2009. Four years later, Croatia joined the European Union, and became a vocal supporter of EU sanctions against Russia.

In late 2016 Croatian prime minister Andrej Plenkovic led an European Parliamentary delegation to Ukraine, where he established a joint Croatia-Ukraine working group to explore the potential for a peace agreement in eastern Ukraine, modelled on Croatia’s 1990 agreement with Slovenia. The visit “raised serious concerns in Russia” according to the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Pitched to be the first Balkan state to take-over the EU presidency in 2019, and potentially to join the Eurozone, Croatia has fast become a bellwether for the future of the Balkan region and its relations with the US, the EU and Russia.

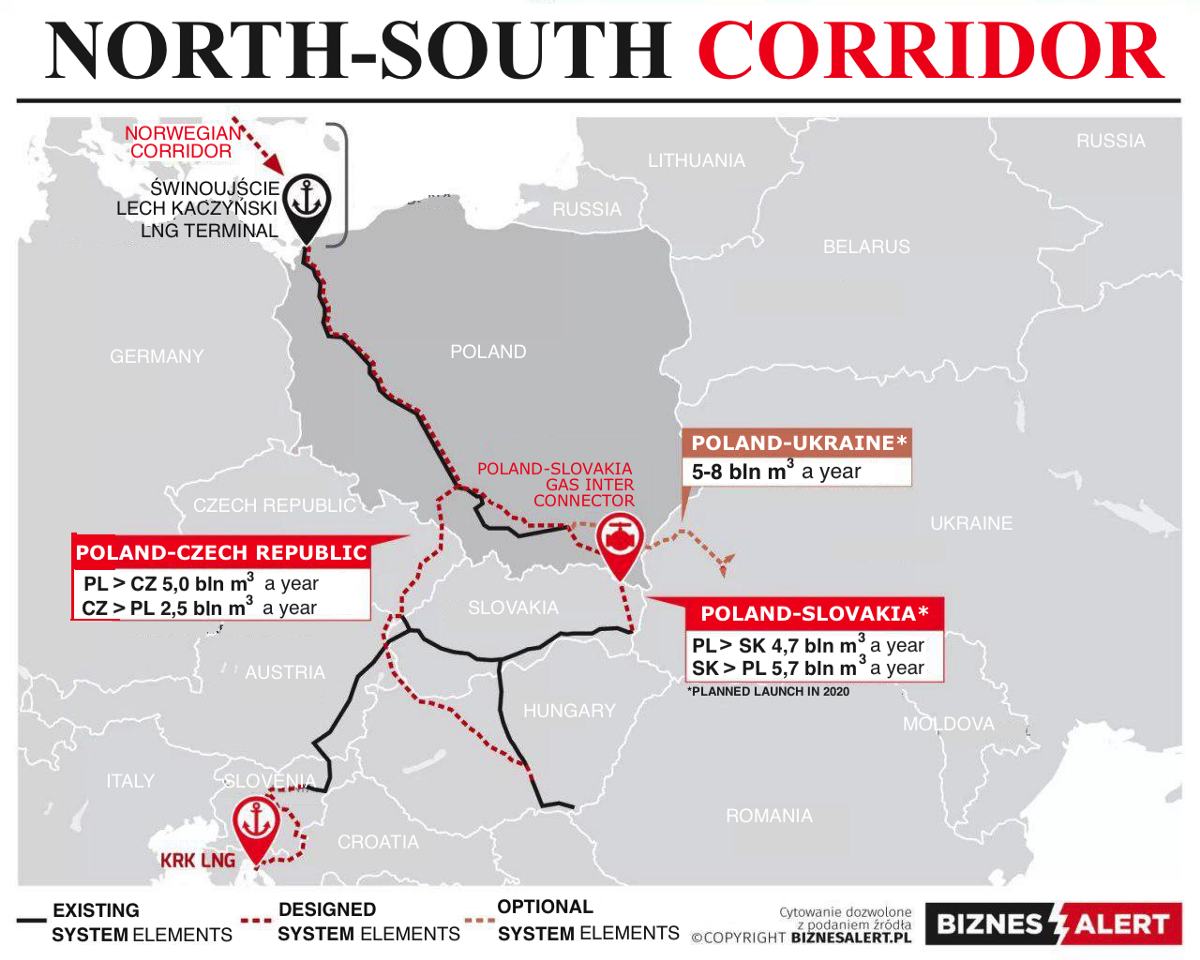

But perhaps the biggest significance of this small country is its little-known ability to determine the future energy map of Europe. Croatia sits at the centre of a web of potential new energy transhipment routes that could, in theory at least, allow Europe to free itself from chronic dependence on Russian gas.

The New Great Game

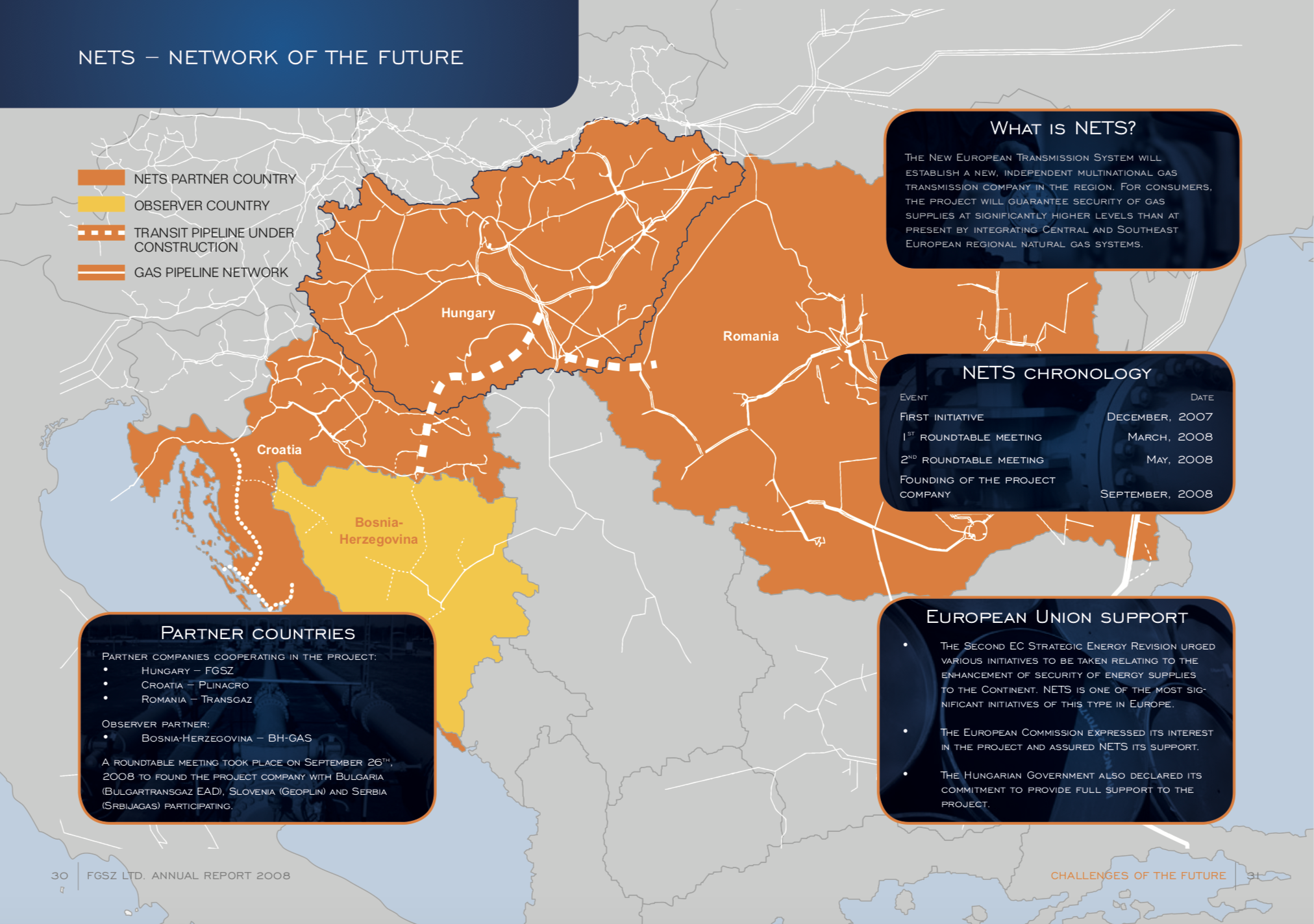

The basic concept was first proposed in 2007 by Hungary’s national energy company MOL. The idea was to build a ‘New European Transmission System’ that would link up all of Central and Southeastern Europe’s gas systems from Poland to Croatia. The proposal was greeted with enthusiasm by the European Commission.

Since then, attention has focused on a key pivot for the proposed gas corridor: Croatia’s port of Omisalj on the island of Krk, where the United States and European Union have pushed the idea of building a new liquid natural gas (LNG) terminal. US and EU officials believe the obscure island could hold the key to European energy dependence, with the potential to turn Croatia into a major regional energy hub and a conduit for the supply of US, Qatari and other gas to Europe.

“Russia is terrified over efforts to construct a new LNG terminal on the island of Krk that would result in LNG being shipped in from the US, Qatar and elsewhere, and sold downstream to other EU-member states,” said one Western diplomat in Zagreb. “The terminal would curb Russian efforts to be the sole supplier of gas to the EU.”

Even as the US and EU have struggled to bring the Krk project to life, Russia has tried every rule in the book to undermine it — ironically, with the help of companies with ties to Trump.

The Krk route is one of the US government’s core missions in the region. Just last October, the State Department issued a new country strategy warning that: “If the Croatian government does not pursue a strategy of energy diversification, Croatia and the region will be increasingly vulnerable to influence by outside interests, including Russia.”

Yet while Russia has tried every conceivable strategy to either scupper or control the Krk project, Trump insiders have ended up facilitating Russia’s rear-guard entry into the Balkans at every step.

The path to the heart is through the belly

In March 2017, Russia found its most potent entry point: Croatia’s largest company, Agrokor — a giant agribusiness conglomerate of 143 companies across the entire Western Balkans — was in deep financial trouble. The company was about to default on 7.6 billion dollars of debt. With some 60,000 employees and total revenues equivalent to 15 percent of Croatia’s GDP, the company’s collapse would have immediately impacted as many as half a million people, triggering a region-wide economic shock.

Agrokor was too big to fail. But after the Croatian government stepped in to bailout the ailing firm, two Russian banks under US sanctions with ties to Donald Trump were the chief beneficiaries — and the deal was arranged by a US hedge-fund with direct ties to the highest levels of the Trump administration.

In April 2017, the Croatian parliament passed into law the government’s ‘Lex Agrokor’ bill, an emergency procedure designed to allow the government to intervene by restructuring and bailing out the company.

Around the same time the following year, leaked email communications obtained by the Croatian news platform Index revealed that senior Croatian government officials had known about Agrokor’s financial woes well in advance, and had planned the bailout in February — about a month before the company was accused of falsifying financial information.

Much of that story is well-known within Croatia. Less well-known is that Ante Ramljak, who had been appointed by the Croatian government as the special administrator to oversee Agrokor’s restructuring, had met a week earlier in March 2017 with representatives of the US hedge-fund Knighthead Capital.

How to buy a country

According to an intelligence memorandum for investors prepared in June 2018 by Bearstone Global, a corporate advisory firm in London’s financial district, the sequence of events raised a legitimate suspicion: “The main red flag here is the question whether Knighthead had insider information about the provisions of Lex Agrokor, before making its investments?”

Not only had Knighthead representatives met with Ramljak before the announcement that he would become special administrator with direct influence on the bailout terms, Knighthead’s co-founder Thomas Wagner had “even admitted in public that they’ve decided on the investment after consultations with the Government,” noted the Bearstone memorandum.

A year after Lex Agrokor became law, Knighthead’s closed-door deal-making resulted in a stunning victory for two Kremlin-backed banks, Sberbank PJSC and VTB Group. The two banks were together handed a huge 47% stake in Agrokor, converting claims of about $1.7 billion in debt to equity.

This was no trivial victory. Russia has “bought itself a NATO country”, remarked Croatia’s Centre for Development Cooperation. Sberbank is Russia’s largest state-owned bank. VTB is the second largest. Both giant banks are known to operate as proxies for Vladimir Putin and his oligarchic power-base.

Yet both banks also have well-documented ties to Donald Trump despite having been under US sanctions since 2014.

As of 2017, Donald Trump and Sberbank happen to share the same defence lawyer, Marc Kasowitz. But the relationship goes back years. In 2013, Sberbank chairman Herman Gref set up Trump’s meeting with Russian businessmen during the Miss Universe pageant in Moscow. The event was primarily sponsored by Sberbank.

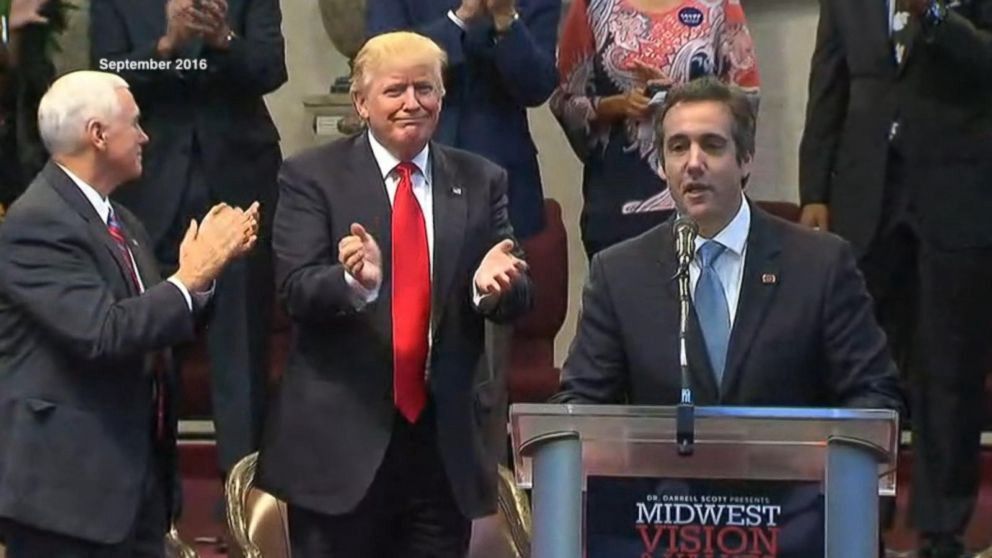

At the time, Trump was on the hunt to pull off a real estate deal in Moscow to build a new Trump Tower and Sberbank had eventually agreed to finance around 70 percent of the project. Trump’s then personal attorney Michael Cohen has admitted that talks for a Trump Tower had continued until June 2016.

In November 2015, the Kremlin-connected Russian fixer Felix Sater — whose real estate firm Bayrock Group had signed a deal with Trump’s company in 2005 — had emailed Cohen about his progress in pushing through the real estate deal. In the email, Sater explained that he had arranged a meeting about it with Putin and one of his “top deputies” — and that the VTB Bank would fund the entire project. “I will get Putin on this program and we will get Donald elected,” Sater wrote in a previous email to Cohen. “Buddy our boy can become President of the USA and we can engineer it. I will get all of Putins [sic] team to buy in on this.”

That’s not the only Trump connection.

Federal filings reveal that the US hedge-fund, Knighthead, which gifted the largest company in the former Yugoslavia into the coffers of Russia’s largest banks, has ties to the uppermost echelons of the Trump administration through two senior officials: Daris Meeks, then Deputy Assistant to the President and Director of Domestic Policy in the Office of Vice President Mike Pence, and Andrew Olmen, Special Assistant to the President for Economic Policy and Deputy Director of the White House National Economic Council.

According to official lobbying disclosure documents filed with the US House of Representatives, Meeks and Olmem are long-time Washington lobbyists from the law firm Venable who have represented Knighthead Capital at various times before, during and after terms in office.

Olmem, who still holds his position in the Trump administration, is among a large batch of Trump appointees who had received ethics waivers giving him a green light to continue lobbying activities unimpeded, and is identified in the documents as lobbying for Knighthead in February 2017 when he joined the White House. Meanwhile, Meeks deregistered from Venable in January 2017, but returned there a year later after his resignation whereupon he continued to lobby for Knighthead.

The Gazprom connection

Although the disclosure filings said nothing in relation to Knighthead’s investments in Europe, while working on the Knighthead account Meeks and Olmem worked alongside another Venable partner, William Nordwind (for instance see here and here).

But about a year before the Venable team began lobbying for Knighthead in 2015, Nordwind — who at the time co-chaired Venable’s Legislative and Government Affairs Practice Group — had been caught secretly lobbying for Gazprom, a relationship he had conveniently failed to disclose to Congress.

Since 2010, Venable had been hired by New York PR firm Ketchum along with its Brussels-based partner-subsidiary GPlus Europe to work on the Gazprom Export account, advising the company on energy policy in the European Union. Gazprom Export exports Russian gas to 27 countries across Europe and the former Soviet Union.

The lobbying contract was revealed in a US Department of Justice disclosure filing, enclosing a Venable engagement letter in which Nordwind identified himself as “the responsible partner in charge” of Venable’s work for Gazprom Export, under a nice retainer fee of $28,000 a month.

Following outraged media coverage of the relationship, Ketchum slashed its formal ties with Putin in 2015. But the relationship was hardly dead. In a statement at the time, Ketchum admitted that it still represented Russia through its Moscow office, and that the same contract with Gazprom continued via Ketchum subsidiary GPlus.

Gazprom lobbyist Nordwind went on to handle Knighthead Capital’s account alongside Meeks and Olmem the following year. After Trump’s inauguration, the disclosure filings show that Nordwind led the account while Meeks and Olmem took a break from this work as they entered their posts in the White House.

The upshot is that two senior advisors to Trump lobbying for Knighthead had worked in partnership with a colleague previously on the payroll of Gazprom’s European interests.

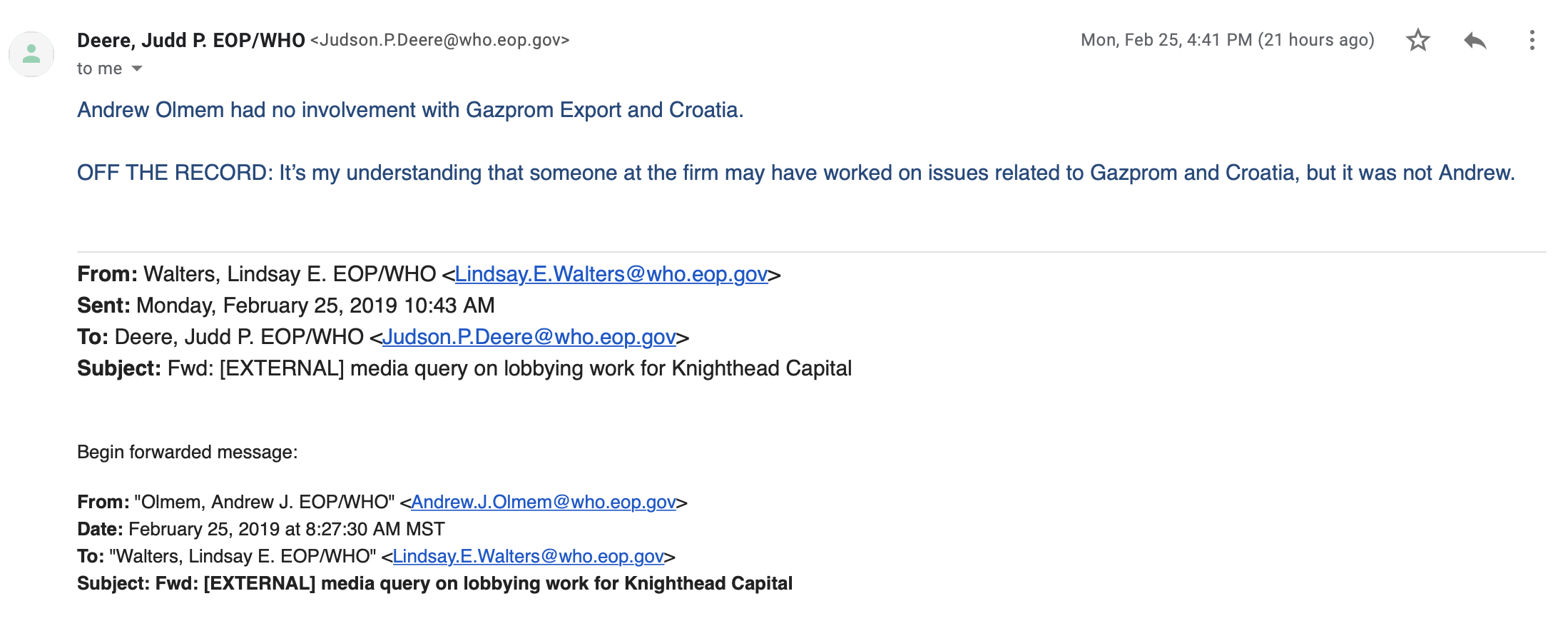

In a statement, White House deputy press secretary Judd Deere told me: “Andrew Olmem had no involvement with Gazprom Export and Croatia.” However, Deere added an unusual off the record comment, which I am reporting here because it contains crucial information in the public interest:

“It’s my understanding that someone at the firm [Venable] may have worked on issues related to Gazprom and Croatia, but it was not Andrew.”

Deere’s astonishing ‘off the record’ statement proves that the Trump White House knew that a Knighthead lobbyist “may have worked on issues related to Gazprom and Croatia”, potentially establishing a direct line of complicity between the White House, Venable, and Knighthead’s activities in Croatia. The White House spokesperson could only have had such an “understanding” of work on Gazprom and Croatia from a senior White House official connected to Venable — likely Olmem himself — who knew about it.

In response to my further inquiries about this off the record admission, Deere denied having any information on Olmem’s colleagues at Venable, ex-White House staffer Meeks and ex-Gazprom lobbyist Nordwind. Neither Knighthead Capital nor its lobbyists at law firm Venable responded to requests for comment.

It is not entirely surprising in this context that the ultimate beneficiary from the Agrokor bailout, negotiated under Knighthead Capital’s leadership, was Gazprom. But before Gazprom got its foot in the door, it needed heavy political and economic leverage, which Knighthead helpfully provided by granting Russian banks Sberbank and VTB their massive stake in Agrokor.

The previous year, Russia’s ambassador to Zagreb, Anvar Azimov, had declared that any Russian assistance on Agrokor would be conditional on Croatia’s “cooperation with Moscow.” And “cooperate” it did.

Having saved Croatia and the wider region from a financial catastrophe, Putin moved swiftly to call in the favour. Within months, Gazprom Export — the Russian energy giant previously represented by Knighthead lobbyist William Nordwind — signed a ten-year gas supply contract with a Croatian oil company, PPD. The PPD has longstanding high-level connections to Croatian government officials, having financed the ruling conservative party, the Croatian Democratic Union, to the tune of 4.2 million kunas in 2016.

Under the new contract, Gazprom would supply Croatia 1 billion cubic meters of gas every year from October 2017 to December 2027, covering 70 percent of the Croatian market. The deal eliminated Croatia’s need for any further imports. It also, therefore, struck a blow against US and EU efforts to encourage Croatia to speed ahead with the Krk project, as it was no longer necessary to cover the country’s immediate gas needs.

Divide and rule

One of the main obstacles to the Krk project is money. To get it off the ground, investors are needed. And they can only be enticed if they know that the gas will find guaranteed buyers. Croatia itself would be a prime customer of gas transported via Krk, but the next major potential buyer is Hungary.

Having shut down the first potential buyer of gas from the Krk route, Russia’s second strategy was to shut down the next. A month after Russia signed the gas supply deal in Croatia, Hungary announced that its gas supply contract with Gazprom, due to expire in 2021, would also be renewed. A year later, Hungary confirmed that Gazprom would continue to supply gas to the country for both 2019 and 2020.

Russia’s third strategy has been to leverage an ongoing dispute between the two countries’ national energy companies — a dispute which seems to have been secretly egged on by interests aligned with both Trump and Putin.

In 2009, Hungary’s national oil firm MOL had acquired a 49 percent stake in Croatia’s state-owned energy company INA. In 2013, Croatia suddenly sought to annul the investment agreement. The Croatian state’s anti-corruption unit, USKOK, accused MOL Chairman Zsolt Hernadi of having rigged the investment deal by bribing former Prime Minister Ivo Sanader. An Interpol warrant was issued for Hernadi’s arrest at Croatia’s request.

According to Jeremy Warner, associate editor at the Telegraph, the Interpol warrant was little more than “a thinly disguised attempt to force the sale of key assets to Russia’s Gazprom.”

Russia has hardly been reticent about where it stands on the issue. In 2014, Gazprom had offered to buy up the entirety of MOL’s shareholding to acquire the Hungarian company’s stake in Croatia’s INA. In 2017, Rosneft followed up with an offer of its own to do the same.

As Croatia has responded coolly to these offers, Russia has tried another strategy. If it can’t beat the Krk project, join it — or rather, control it. Earlier last year, Russia had offered to singlehandedly underwrite the entire development of the Krk terminal with potentially billions worth of investments — throwing in the promise of further cheap Russian gas supplies to boot.

This has led some experts to speculate that the Interpol warrant was engineered by Russia. General Alexander Prokopchuk, Interpol’s Vice Chair for Europe, has been described by Marina Litvinenko, widow of poisoned dissident Alexander Litvinenko, as a close ally of Putin. He has been accused of repeatedly using Interpol to issue arrest warrants for political dissidents opposed to Putin.

Equally, a number of sensitive sources in the region believe that elements of the US government had played a role in the Interpol warrant.

One Croatian diplomat based in an EU capital said that USKOK’s request alone would not be enough to trigger the Interpol warrant. “Only the Americans had enough clout to get that ball rolling”, he added.

A senior Croatian law enforcement official said he was aware that:

“The Americans had used their influence to have Interpol act as the mechanism through which to have Hernadi extradited.”

If true, the Interpol warrant may well have been the result of pressure from both Russia and elements of the Trump administration.

Team Trump targets Croatia

We cannot know for sure, although circumstantial evidence of a common approach between interests linked to both Trump and Putin emerged earlier last year when a major US firm close to Trump’s inner circle made an offer to Croatia premised on MOL breaking relations with INA.

In March 2018, the Croatian government received a letter from American conglomerate Castleton Commodities International (CCI), expressing interest in becoming INA’s “strategic partner” to assist in repurchasing MOL’s shares in the Croatian state energy firm.

“CCI would take over the role of a strategic investor and partner in INA, supporting the Croatian ministries in a range of key sectors,” reads the letter from CCI’s Fabrizio Zichichi. The letter offered help in “securing the financing and as an investment partner, as a commercial partner in contract relations such as the processing of raw oil and oil products, the trade and supply of final products, risk management, running investment projects in all business segments and HR management”.

At first glance the offer looks like a straightforward effort to compete with Russia, especially given that US officials have publicly expressed concern over Russia’s overtures to Croatia to purchase MOL’s shares. But a closer inspection suggests an alarmingly different view.

It was not entirely clear whether CCI’s offer would necessarily reject Russian overtures. And unlike the offers from Gazprom and Rosneft, the letter had not committed CCI to being ready to buy out the entire MOL stake — or ruled out helping another entity, whether Russian or otherwise, to buy in partially. Instead, the letter hinted at the latter by referring vaguely to the prospect of “securing financing” in addition to investing.

What remains clear are CCI’s connections to Trump, and internal sympathies with Russia. The US metals giant and energy trader was a long-time major client of Jay Clayton, Trump’s appointee to Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Clayton was previously senior partner at law firm Sullivan & Cromwell, where he profited from the firm’s work advising a wide range of companies doing business with the Russian government and Russian oligarchs.

These included multi-billion dollar energy projects involving efforts by the Russian government, Lukoil and Gazprom to export Russian gas to Central Asia through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium and to Central and Southeast Europe via the South Stream pipeline project. The latter involved contracts with Bulgaria, which Putin pushed through politically by deploying strategic investments from VTB, the Trump-connected bank which invested in Agrokor.

CCI itself was formed in 2012 when a group of hedge-fund and commodity trading hot-shots bought an energy trading business, LDH Energy, from its umbrella company Louis Dreyfus Group, majority-owned by the wealthiest woman in Russia, Margarita Louis-Dreyfus.

Clayton was involved in that deal too according to his own Wall Street bio, which was deleted after his SEC appointment.

The purchase helped fund Louis Dreyfus Group’s agricultural expansion. Operating in Russia, it is one of the largest agricultural conglomerates in the world, working in partnership with various Russian investment firms and regional Russian government agencies.

The deal saw LDH Energy’s former chief executive, William C. Reed II, move to head up the new company, CCI. Reed also has ties to Russia. He began his career as a junior energy trader at Enron, where he ended up becoming head of power trading. Before its collapse, Enron played an instrumental role in Russia’s energy assault on Europe, signing a historic agreement with Gazprom to supply gas to Russia in 1993. This set the course for Europe’s future growing dependence on Gazprom. Five years later, Enron signed a further 10-year ‘strategic alliance’ with Russia’s Unified Electricity Systems (UES) to identify joint projects in Russia, Europe and Central Asia.

Fabrizio Zichichi, CCI’s Global Co-Head of Oil Liquids, who signed the offer letter to Croatia, was previously Global Co-Head of the Physical Oil Business at Morgan Stanley. Zichichi had moved to CCI from Morgan Stanley after buying its giant physical oil merchant business for $1bn.

That deal, also advised on by Jay Clayton, only went ahead because the first choice had fallen through: Zichichi and his colleagues had already agreed to sell the business to Russian state-owned oil company Rosneft. The Rosneft deal fell through only because US sanctions were put in place due to the Ukraine conflict.

So the CCI offer was not just aligned closely with Trump’s inner circle — it came from executives with a history of sympathetic economic engagement with Russia, Gazprom and Rosneft. Requests for comment were sent to CCI and the SEC but received no reply.

Even more curiously, just over a month after the CCI offer letter went out, US Attorney General Jeff Sessions — who surfaced in the Trump-Russia collusion inquiry for lying about meetings with Russian government officials during the presidential campaign — made an unprecedented visit to Croatia.

Sessions met a number of senior Croatian government officials, including President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, Prime Minister Andrei Plenković, Justice Minister Dražen Bošnjaković, Interior Minister Davor Božinović as well as Foreign Affairs Minister Andrej Metelko-Zgombić.

Public information on what was discussed during this strange diplomatic excursion is sparse. According to a statement from the US embassy in Croatia, Sessions’ visit was to “discuss bilateral and international law enforcement and judicial cooperation and discuss ways of further strengthening the close law enforcement relationship between the United States and Croatia.”

The US Department of Justice refused to provide me any further details on what this excursion was all about.

Then later that year, the Interpol warrant for MOL’s Hernadi — which had been dropped two years earlier after Hungary refused to comply with it — was suddenly renewed in November 2018.

The new Interpol warrant was issued weeks after US Energy Secretary Rick Perry urged Hungary to resolve its issues with Croatia and support the US-EU backed gas hub project in Krk.

Whoever was behind the Interpol warrant — elements of the Trump administration, Russia or both — it served to make the rapprochement that Perry was publicly calling for far more difficult in reality. Of course, Trump has refused to put money where Perry’s mouth is, failing to offer any financial support for the Krk project — unlike Russia.

There are strong grounds to doubt that the warrant was even justifiable. The basis of the warrant was rejected in 2014 when an arbitration tribunal convened under UNCITRAL, the UN’s highest trade law body, threw out Croatia’s case against Hernadi because it relied almost entirely on the testimony of a single witness in the absence of any material evidence — a witness representing an unexpected convergence of interests stretching from Putin to Trump.

Trial by oil

That witness, on whom the future energy map of Europe might depend, is a little-known Croatian tycoon named Robert Jezic, who happens to be connected to two Russian oligarchs, one of whom also has ties to Trump’s disgraced lawyer Michael Cohen.

Jezic is the main witness for the claim that MOL chairman Zsolt Hernadi bribed a former prime minister to push through MOL’s big buy-out of Croatia’s state oil firm.

At the time of the alleged bribe, Jezic was head of the board of Dioki, a petrochemicals plant which operated on Krk, the island where the US and EU hope to support the Croatian government in building a new gas terminal.

But court testimony has alleged that Jezic’s bribery allegation against Hernadi conceals his role as a business partner in a secretive Russian effort to take control of the island. That testimony came from Russian billionaire, Mikhail Gutseriyev, owner of the seventh largest Russian oil company Russneft.

Gutseriyev, who is on a US Treasury list of Russian oligarchs with close ties to Putin, told a Croatian court in 2012 that he had invested €5 million through Jezic’s company, Dioki, to purchase land in the strategic port of Krk. The investment fits with Russia’s broad strategy of attempting to either disrupt or dominate the Krk project.

Unfortunately for the Russians, Jezic had simply stolen the investment — at least according to the oligarch, a claim strenuously denied by Jezic. To complicate matters further, although Jezic was ordered by a Croatian court to return the missing €5m seven years ago, he simply failed to do so.

Gutseriyev himself is a prime beneficiary of murky deals which lead directly to Trump. According to The Globe and Mail, the oligarch’s eldest son, Said Gutseriyev, controls Cypriot shell companies which own shares in a major Russian locomotive factory, a project financed entirely by Kremlin-run bank, VneshEconomBan, or VEB.

Despite being under US sanctions since 2014, VEB’s then chief executive Sergei Gorkov met with Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor, in the Trump Tower after the 2016 election. The Gutseriyevs also happen to own the Hotel National, where Trump stayed during his first visit to Moscow in 1987.

Gutserieyev’s company, Russneft, was also a big beneficiary of a spike in Russian stocks after Trump’s election victory. Russia’s Micex index rose 3.8 percent, and oil and gas stocks rose 3.7 percent. Days after the election, the Trump-connected banks VTB and Sberbank coordinated the launch of a long-planned IPO for Russneft, which raised $500m.

Russneft is part-owned to the tune of 33 percent by the mining giant Glencore, which in December 2016 co-purchased with the Qatar Investment Authority a 19.5 percent stake in Rosneft, with VTB’s support. That deal seemed to cohere with the Steele dossier’s prescient claim that Rosneft had offered Trump through his advisor Carter Page “the brokerage of up to a 19 per cent (privatised) stake in Rosneft” in return for easing sanctions on Russia.

Jezic’s connection to Russia’s efforts to control the Krk project for its own ends were further corroborated in 2017. Jezic’s company, Dioki, had gone bankrupt in 2013 because it had been unable to pay off its loans — a major creditor was Austrian bank Hypo Alpe Adria. But four years on, a company called Gasfin had taken over the outstanding debt originally owed to Hypo.

Gasfin became the owner of the key area of land in Krk where the proposed LNG terminal is to be built. The company has pushed for an onshore solution, in contrast to US and EU calls to build an offshore terminal due to the inability to get control to the land. Though based in Luxembourg, Gasfin is widely viewed as a proxy for Russian interests — it is operating a number of projects in Russia, including building a major infrastructure project for Gazprom.

The Michael Cohen connection

Court records and testimony further confirm that the disappeared money, which Gutseriyev claimed was stolen from him by Jezic, was funnelled through another company of which Jezic was a shareholder, Xenoplast, whose executive director is Swiss lawyer Stephan Hurlimann.

Jezic, other witnesses, and Hurlimann himself have confirmed that the missing €5m was paid into his company Xenoplast’s account. But Hurlimann, who has refused to testify in person in Croatian courts despite multiple requests, had another very odd connection: Trump’s friend, a Russian oligarch, controls a company directly tied to his Swiss law firm.

Hurlimann is partner in the firm Wenger & Vieli. The law firm boasts of dealing with Russian clients, but does not identify them. A glimpse at the kind of clients it deals with emerges from the fact that Wenger & Veili has direct ties to firms controlled by a Putin-linked oligarch, including a company which secretly paid Trump’s disgraced lawyer Michael Cohen.

Hurlimann’s fellow senior partner in Wenger & Vieli is Dr Wolfgang Zurcher, who since 2014 has sat on the Board of Directors of Zublin Group in Zurich, which is majority owned by the Russian billionaire oligarch Viktor Vekselberg. Wenger & Vieli did not respond to request for comment on this apparent conflict of interest.

Dr Iosif Bakaleynik and Iakov Tesis, two Vekselberg proxies, are representatives of the largest shareholding (40.7 percent) in Zublin, Lamesa Holding. Both are involved in Vekselberg’s Renova Group. To represent Vekselberg in Zublin, Bakaleynik, who continues to advise the oligarch, left his previous posts as chairman of the board of Renova Management and chairman of the supervisory board of Renova US Holdings, a subsidiary of the Renova Group. Tesis is still a director of Renova Group in Russia, and also acts as the authorised representative of the shareholder of GAZEX, a joint venture between Gazprom and Uncomtech.

Vekselberg and his Renova Group, which have been under US sanctions since April 2018, have controversial ties to Donald Trump. Both Vekselberg and his cousin Andrew Intrater had met Trump’s attorney Michael Cohen in person in Trump Tower, just eleven days before the presidential inauguration in January 2017, where they discussed improving US-Russia relations.

Later that year an affiliate subsidiary of Vekselberg’s Renova Group reportedly made substantial payments to Cohen’s account totalling at least half a million dollars.

The subsidiary, Columbus Nova, has been described in federal regulatory filings as an affiliate of the Renova Group, and Renova’s own website once listed Columbus Nova as part of the group. In 2017, Columbus Nova’s CEO Intrater also donated $250,000 to Trump’s inauguration fund and $35,000 to a joint fundraising committee for Trump’s re-election and the Republican National Committee.

And so the circle closes, though not without raising more questions than answers.

Robert Jezic’s direct and indirect alleged ties to Russian oligarchs friendly with both Trump and Putin raise questions about his credibility as the key witness in a case that has soured relations between Hungary and Croatia for years.

He was not only an alleged business partner of a Russian oligarch who owns one of Russia’s biggest oil companies, and wanted to buy up land in Krk; his debts have been absorbed by a company working closely with Gazprom which now controls that land in breach of European interests, and his Swiss law firm has ties to the very sanctioned Russian oligarch implicated in hiring Trump’s personal attorney after Trump was already in power.

It is not unreasonable to wonder whether these cross-cutting interests compromise the integrity of his claims, both past and present, and point to a pattern of behaviour that in different ways could well be serving those dubious interests.

So far the focus of the Trump-Russia collusion inquiry has been on the US presidential elections. But this investigation suggests that the inquiry may have overlooked the heat of the action.

There is mounting evidence that Trump’s liaisons with wealthy Russians, amply lubricated within the murky sinews of global finance, has set the scene for what is happening right now: Russia’s sophisticated pincer movement to consolidate control over Europe’s gas supplies.

The Steele dossier has been a polarising force, with many of its claims hotly contested. One of its suggestions was that Trump’s approach to the Balkans would end up playing into Russian energy interests. This investigation has shown that contention to be accurate.

People and companies who operate as part of Trump’s inner circle have not only systematically interfaced with Russian interests, they have done so in a way that has strengthened Russia’s hold on the Balkans, weakened efforts to pursue alternative energy transhipment routes, and undermined efforts to end Europe’s chronic dependence on Russian gas – all at a time when the world needs to urgently wean itself off fossil fuel dependence to avert dangerous climate change.

Some might consider this treasonous. Trump? He’d probably say it’s just business.