The Middle East crisis is rapidly spiralling out of control. Conventional analysts have failed to understand its global systemic drivers and its potentially catastrophic consequences on a global system scale. Using the lens of the planetary phase shift framework, however, helps us to recognise the unfolding conflict across Israel, Gaza, Lebanon and Iran as not just a regional breakdown, but a global systemic rupture in the context of the planetary phase shift as industrial civilisation moves through the last stages of its life-cycle. Understanding this moment through a systems lens is therefore crucial to avoid the imminent risk of global synchronous failure - which could lead to paralysis and collapse in a manner that derails emerging possibilities of systemic transformation.

Following the devastating killings of over 1,200 Israelis and injury of over 5,000 by Hamas in the 7 October terrorist attacks (including some 816 civilian men, women and children), Israel immediately launched its own wave of terror across Gaza - resulting in the wholesale destruction of some 80% of schools, 60% of farmland, over 55% of all civilian structures, the killings of over 41,000 Palestinians and mass displacement of over 2 million. More women and children have been killed over a single year in Gaza by the Israeli military than in any recent conflict over the last two decades.

As Israel began bombing Gaza on 7 October, Hezbollah launched what it described as retaliatory strikes the following day by firing rockets into the Shebaa Farms region on the Lebanese-Syrian border in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. Since then, strikes and counterstrikes across the Lebanese-Israel border intensified, resulting in over 100,000 Lebanese and 60,000 Israelis being displaced.

As hostilities have intensified, Israel’s assassination of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah was the trigger that pulled Iran, Hezbollah’s principal state-sponsor, directly into the rapidly escalating conflict.

The assassination came as part of a full-scale Israeli ground invasion of southern Lebanon, which within a few days saw well over a thousand Lebanese civilians killed and homes destroyed, and over a million Lebanese civilians – a fifth of its population – displaced.

On 2 October, Iran attacked Israel directly with a flurry of ballistic missiles. It was, in the words of US President Joe Biden, “ineffective” – damaging some airbases, a Mossad building, a school and several homes in Israel. The only casualty of the attack was a Palestinian resident in the occupied West Bank.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu then vowed that Iran will “pay” for the attack, raising the prospect of an imminent all-out war between Israel and Iran that could degenerate into a protracted regional conflict.

Planetary phase shift

How can we understand this using the lens of the planetary phase shift?

Here, we’re going to quickly remind ourselves of the core conceptual tools of the planetary phase shift framework that could help us. We’ll then explore how applying this framework can help us make sense of the regional and global systemic dynamics driving the escalation of the conflict. The civilisational risk implications of the conflict, and in particular its corrosive effects on the planetary phase shift, will then be laid out.

Civilisations, like all major natural systems, move through a life-cycle of four stages - growth, stabilisation, release and reorganisation. The final stage either precipitates a new life-cycle, or the death of the system.

The planetary phase shift framework indicates that human civilisation, as the largest socio-ecological system on the planet, is moving between the third (release) and fourth/final (reorganisation) stages of its life-cycle.

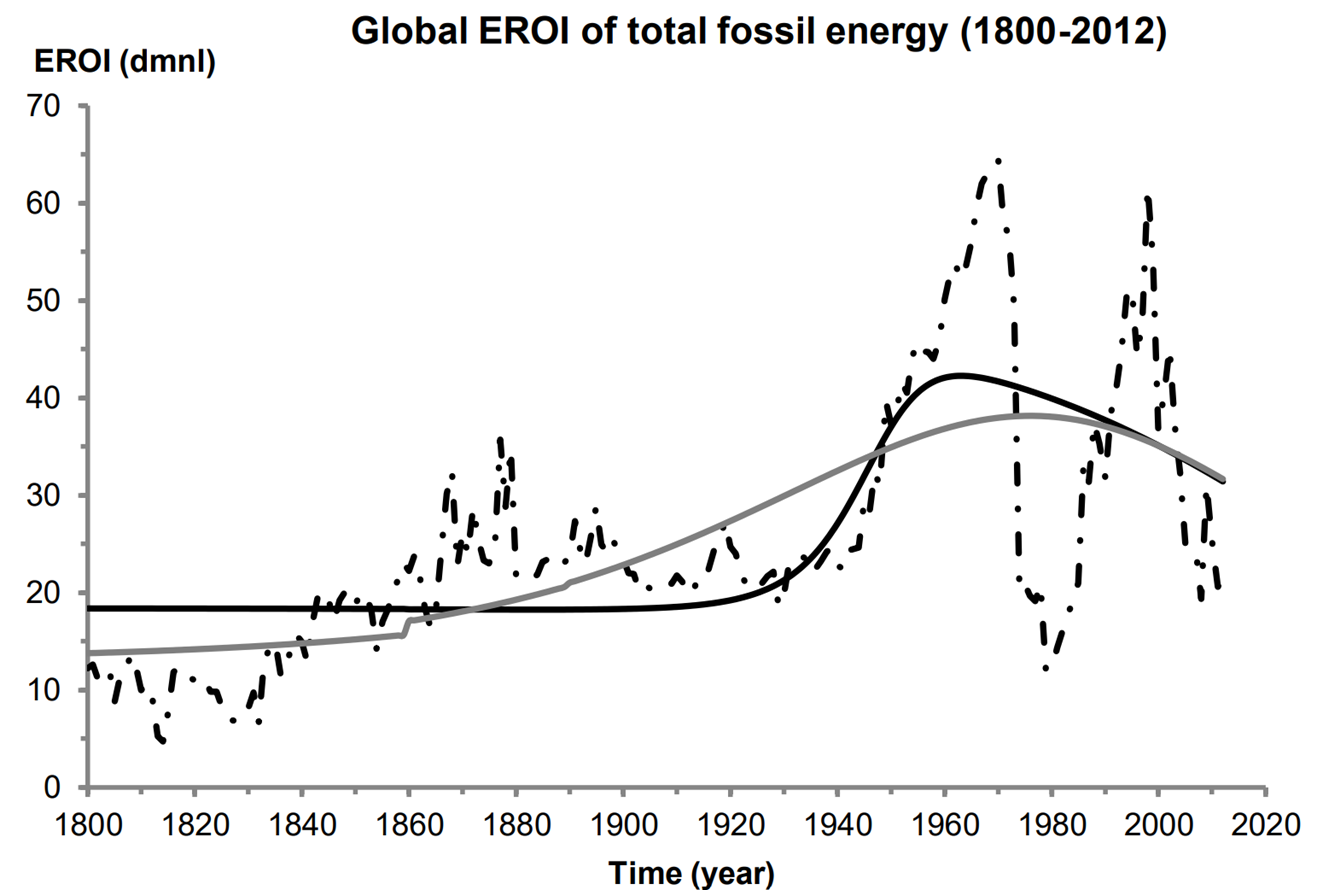

This conclusion is supported by empirical data across many of the defining material sub-systems of civilisation and its interactions with planetary life-support systems. We not only have extensive data that industrial civilisation is at risk of breaching significant ‘planetary boundaries’ of which the climate system is just one, we also know that the global Energy Return On Investment (EROI) of fossil fuels has been declining dramatically since the 1960s.

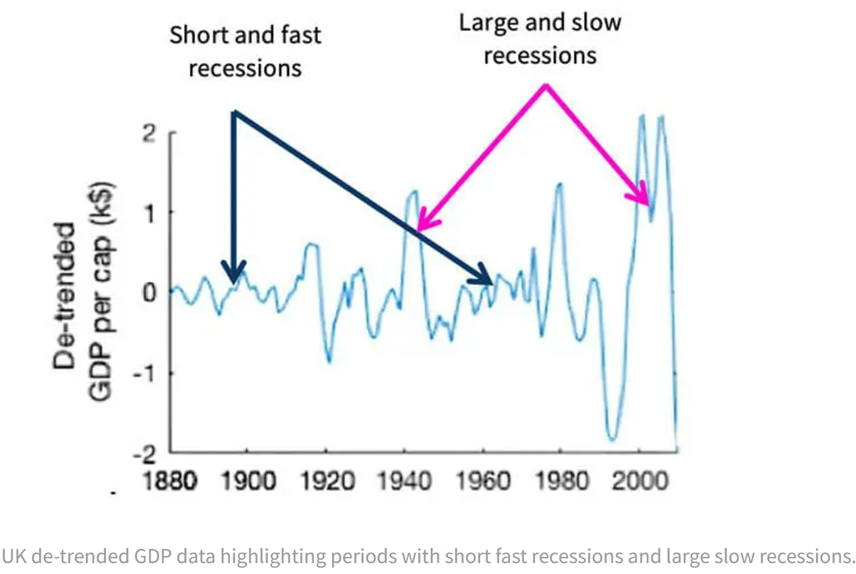

This has acted as a fundamental systemic driver of a steady decline in the rate of global economic growth. An increasing reliance on financialisation through debt expansion has attempted to compensate for this, but ended up compounding the systemic volatility of the financial system, resulting in periodic global and regional debt crises.

These major energy and economic shifts are intertwined with major production system crises facing legacy industries across food, transport and information. These escalating crises are, therefore, not simply multiple disparate events that happen to be deeply interconnected due to complex relationships. They are actually different sector extensions of a single, fundamental systemic crisis in humanity’s relationship with the planet (a reality which crude conceptualisations of the ‘polycrisis’ tend to obfuscate).

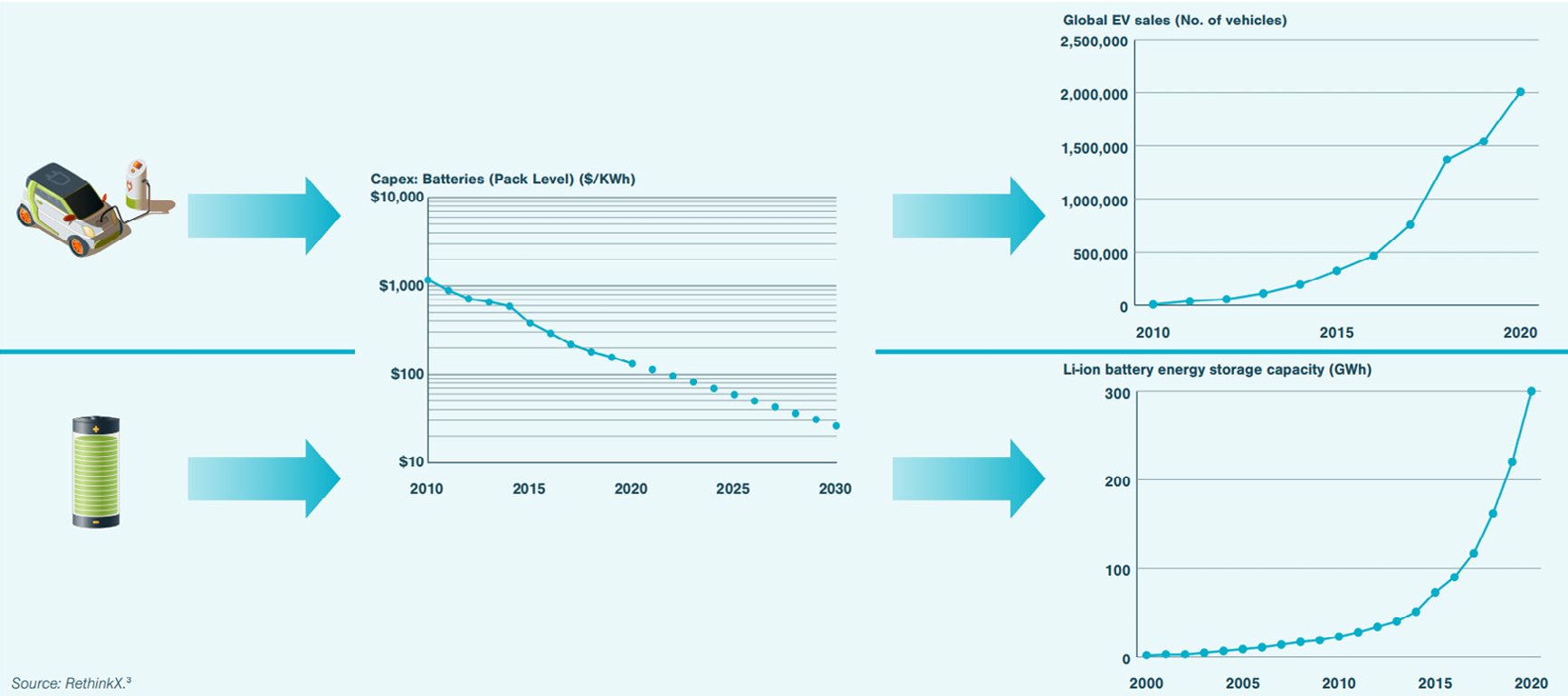

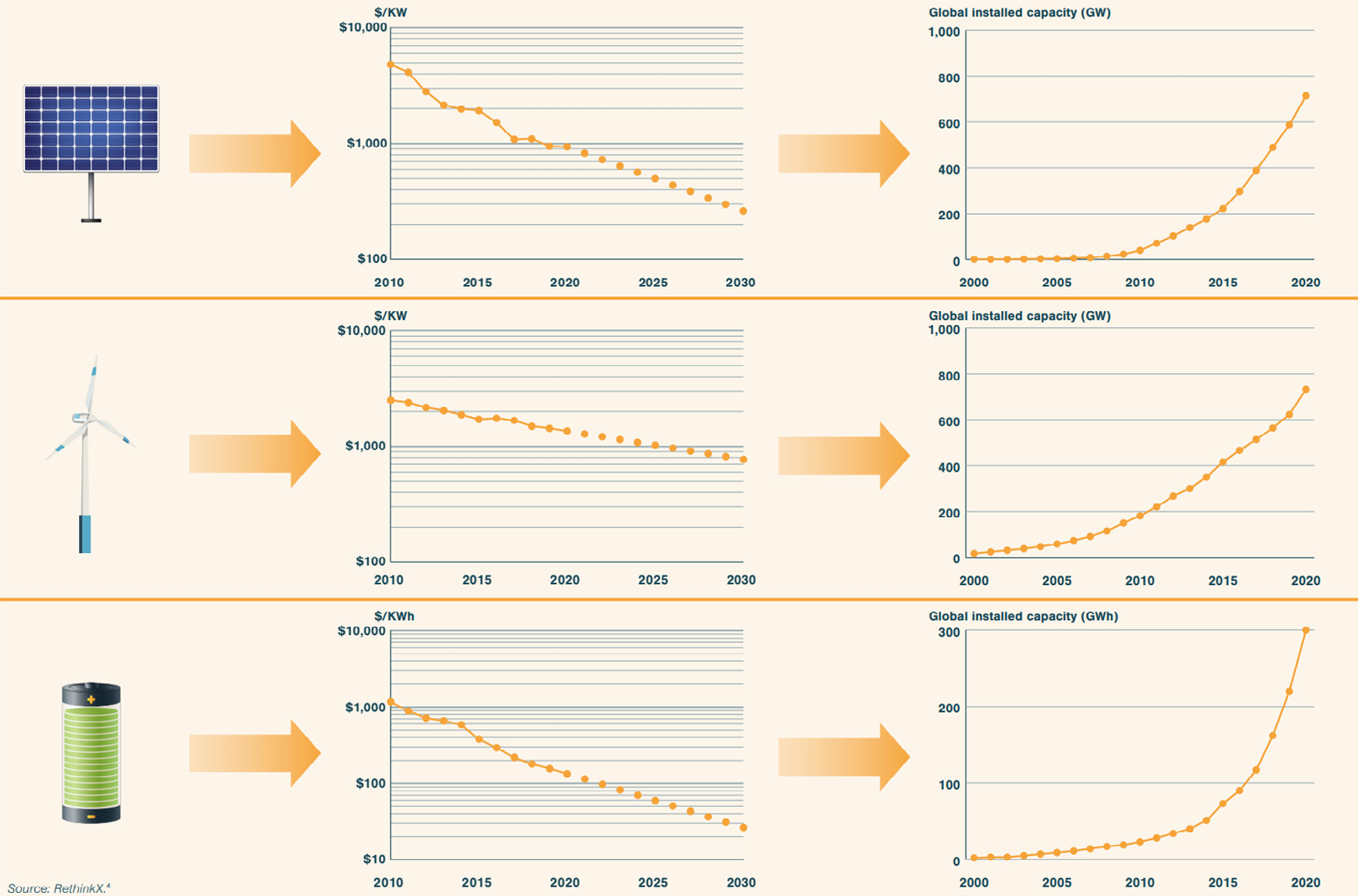

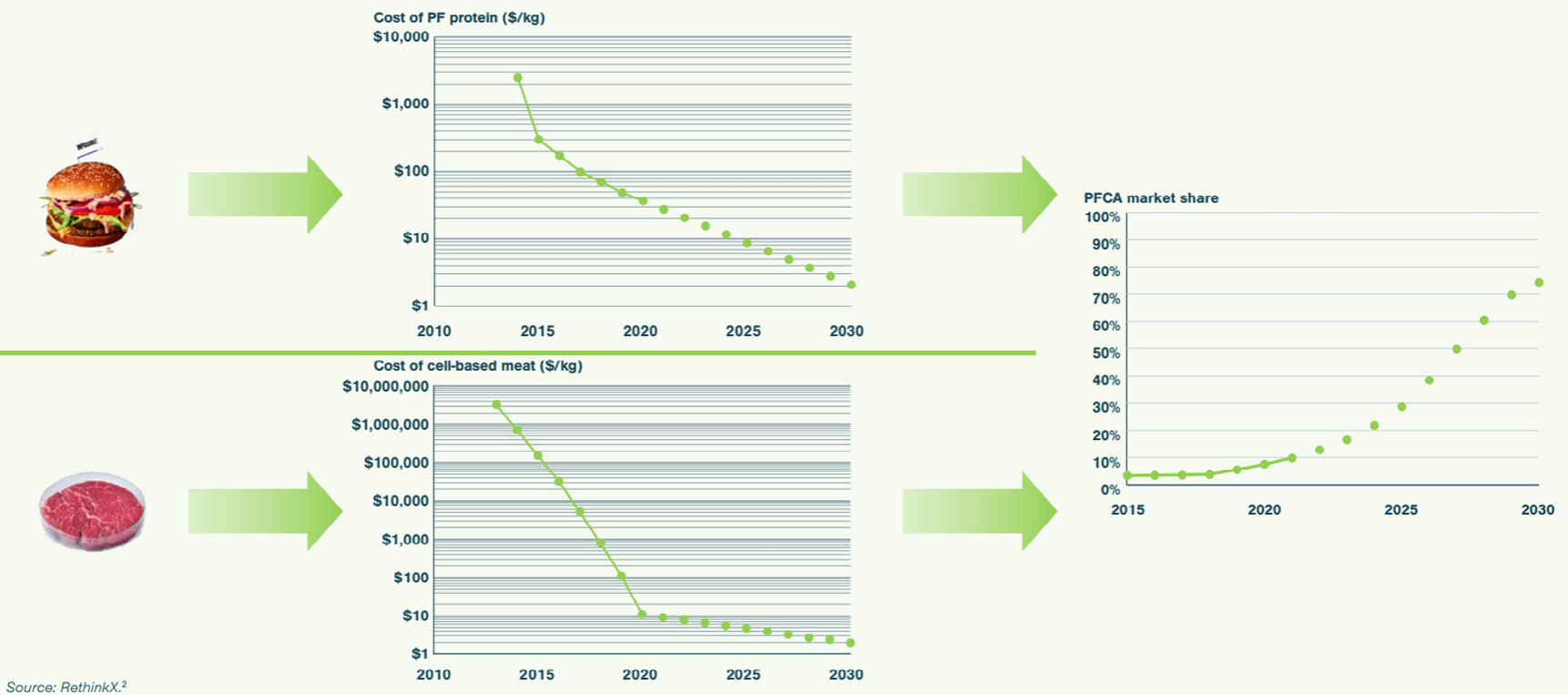

Simultaneously, we are moving into a new reorganisation stage in which these very sectors and systems are being reshaped and restructured. Among the major drivers of this process is the emergence of disruptive technologies across energy, transport, food, information and materials which are outcompeting incumbent industries and technologies, and on track to disrupt and displace them. These are not one-for-one substitutions but as they have completely distinctive properties operating according to novel rules, they entail entirely new systems of production.

Yet the most challenging aspect of this planetary phase shift is the role of what might be called the ‘software’ of civilisation – our cultural systems, or civilisation’s “organising system” (OS).

As we move through the third release and fourth reorganisation stages of the planetary phase shift, we are not only witnessing crisis-collapse trajectories in incumbent material structures, we are simultaneously witnessing crisis-collapse trajectories in the dominant ideologies, paradigms, and intertwined social, political and economic structures of industrial civilisation. These are being compounded by the rapid emergence of new material tools and systems of production whose operation can barely be managed or regulated by the incumbent OS.

There is thus a a huge and widening gap opening up between

1. Incumbent material systems breaking down;

2. emerging new material capabilities;

3. and incumbent cultural paradigms and OS structures.

Now this is where things get more relevant to understanding geopolitical wild cards such as what’s unfolding in the Middle East.

This information gap means, in simpler terms, the 'hardware' of civilisation is experiencing a chaotic metamorphosis as the old system breaks down in the wake of emerging new systems, but the 'software' of civilisation - adapted to manage the old system - cannot keep up.

Looking at the Middle East through a systems lens

Moving through these last stages of the life-cycle of industrial civilisation feels incredibly destabilising. It's why we are experiencing heightened potential tensions over resources that could amplify the risk of conflicts.

In the case of Israel-Palestine, it’s clear that the conflict has been radicalised by competing claims over resources – especially land and fossil fuel reserves – yet perhaps the biggest factor reinforcing the tendency to extreme violence has been the role of local manifestations of the industrial OS, as refracted through established repressive political structures.

On a planetary scale the incumbent industrial OS - encompassing worldview, values, governance systems, culture, and so on - is a fundamental constraining factor in the human capacity to scale through the planetary phase shift and successfully reorganise. Transformation requires a fundamentally new OS empowering us to understand our predicament, transcend our dying industrial paradigm, and align our material and cultural systems with planetary life-support systems.

This is simultaneously the case at regional and local levels. In the Middle East crisis, all actors are constrained by old paradigm ideologically-limited OS structures and values which interpret events through the lens of ethnonationalist categories, broken models of political engagement, and hierarchical modes of dialogue.

Predatory extraction

Whatever you believe about the history, rights and wrongs of this conflict, it is incontrovertible that the Israeli-PA-Hamas system is a fundamentally extractivist structure of regional resource exploitation and distribution. Indeed, Western support for Israel has been bound up with longstanding goals to monopolise access to Middle East oil.

That system is maintained through an overarching system of political and legal regulation which is enforced militarily. In this structure, land, water, energy and food resources are overwhelmingly monopolised by an ethnically and religiously defined group (Israelis) at the expense of other ethnically and religiously defined groups (Palestinians). Within these groups, there are also sub-groups of hierarchical control and exploitation.

What is clear is that this defunct paradigm is now imploding, because it is constraining perceptions of what’s possible and thereby limiting the range of perceived choices to ones that involve escalating indiscriminate violence.

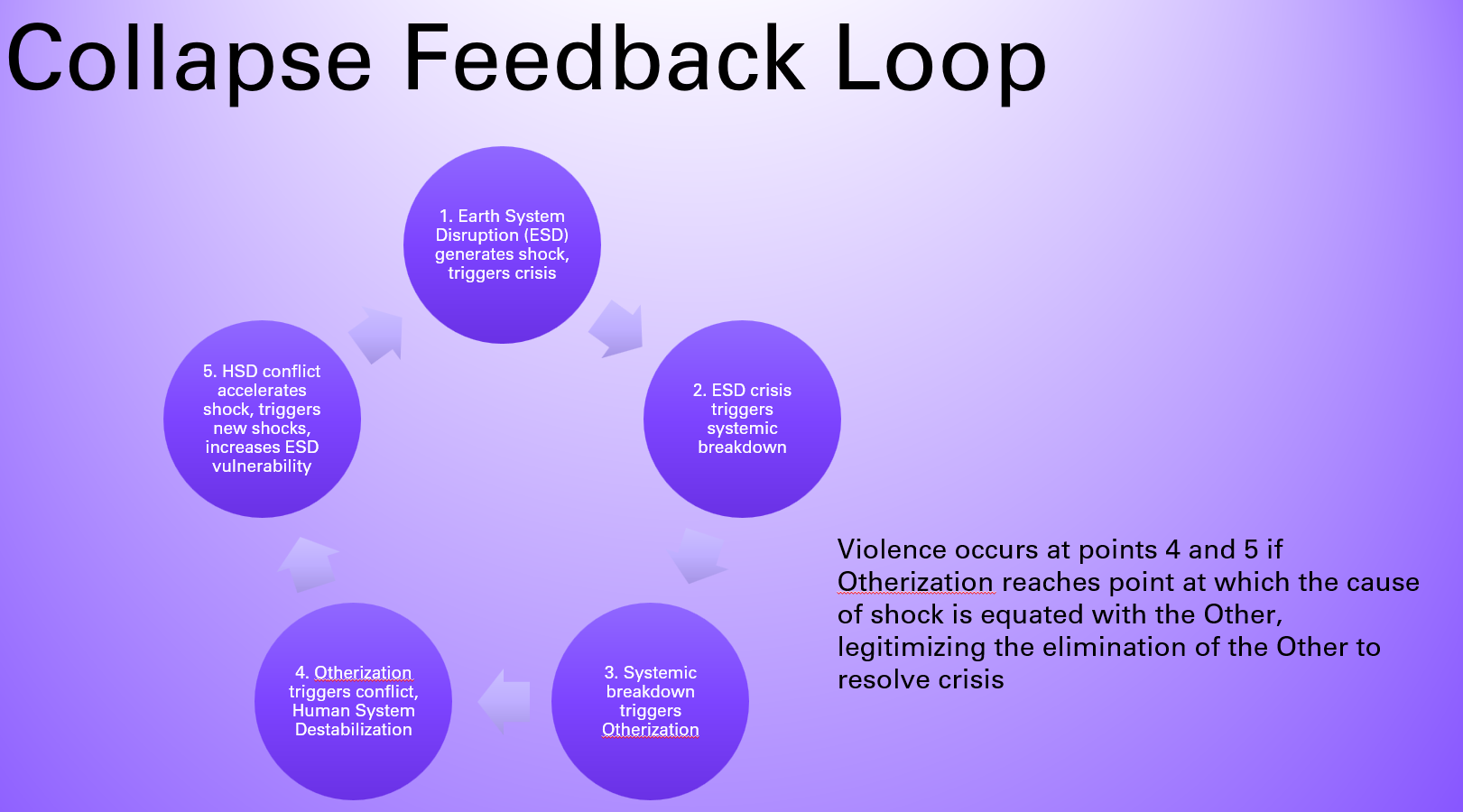

This is due to an ‘Otherisation’ dynamic that scholars of conflict and genocide will be familiar with. When a system enters a state of crisis, people within it can often polarise into exclusionary group identities which are then scapegoated as the source of the crisis.

This usually happens in the context of an incumbent OS whose dominant ideology and worldview is incapable of recognising the system driving the crisis, and instead therefore leads people to become obsessively preoccupied by the surface symptoms of crisis (whether that is migration, unrest or violence, or something else).

By then responding primarily to symptoms rather than addressing the underlying system, actors can find themselves in a self-reinforcing feedback loop of destabilisation which fails to address the systemic drivers of crisis (that therefore continuously worsens, in spite of, indeed often because of, prevailing responses).

As the global system moves through the release stage and toward reorganisation, then, one thing that can happen is that interest groups and industries who are tied to the incumbent production system and OS, instead of embracing the need for change, double-down to protect dying incumbent structures – whether material or cultural.

This shows up as a mutual radicalisation process. We witness this in the regional conflict where all sides are hardening their traditional strategies. We see a concerted social polarisation effect in which mutual exclusion and Otherisation is reaching extreme levels increasingly justifying larger applications of mass violence as a solution. We also see a tendency to fall back on entrenched old paradigm ideologies in the region.

Doubling down on the old

For Israel we have seen how over the last decade this has resulted in the intensification of the settler-colonial paradigm, with expansion of illegal settlements in the West Bank, tightening draconian control on Gaza (such as its food and water resources and movement of people) – all policed using periodic counterinsurgency violence that has grown increasingly brutal and indiscriminate according to Israeli human rights observers.

This reality has been summarised well by BT'selem, the Jerusalem-based Israeli human rights group:

It was over fifty years ago that Israel occupied the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, part of which it annexed to Jerusalem... In order to expand and consolidate control over the lands it occupied, Israel has applied myriad military, civilian, legal and administrative measures through which it has torn apart Palestinian space, divided the Palestinian population into dozens of disconnected enclaves and unraveled its social, cultural and economic fabric.

The Gaza Strip was converted by Israel into the world’s largest open-air prison. In the West Bank, Israel allocated to settlements most of the rural area outside the Palestinian enclaves, including land in the area it annexed to Jerusalem, bringing about a fragmentation of Palestinian space and resulting in Israeli takeover of the land.

The disparate units Israel has created in the Occupied Territories differ from one another, based on how Israel defines them, the status it has accorded their residents and its plans for each area. Regardless, for over fifty years, all the Palestinians suffer a daily reality of dispossession and oppression under Israel’s control. Israel runs their lives, denies them political rights and a voice in determining their future.

For Hamas we have seen that this has culminated in the resort to periodic rocket attacks on Israel, culminating in the devastating terrorist atrocities of 7 October inside Israeli territory which killed the largest number of Jewish people since the Holocaust.

This system of violence – where Israel is, incontrovertible empirical data shows, consistently responsible for the overwhelming majority of exclusionary mass violence – has now spiralled into a year-long genocidal war on Gaza as a whole, a potentially or tendentially genocidal invasion of Lebanon and the prospect of all-out-war with Iran.

Seeing the 'release'/collapse stage unfold in Gaza

The global systemic risks of this moment are difficult to comprehend. Engagement in futile and protracted military confrontations is a hallmark of imperial overreach that precipitate systemic decline, because it is usually a symptom of that decline process.

Past imperial civilisations (think Rome, or Britain) that have entered the release stage often collapse in the process of using military force to contain the violence that erupts in the very context of collapse.

A hallmark of the release stage is therefore a heightened degree of irreducible uncertainty which means it is inherently challenging to predict with reliability what happens next not because of a lack of information – but because the system itself has entered a state of undetermined flux which could go on many divergent directions depending on the decisions of sub-system actors.

It's precisely in the context of that uncertainty that actors seek to construct certainty in the familiar and comfortable tropes of incumbent ideology, and the idea that we can become 'great again' if only we do more what once supposedly made us great in the distant past.

Hardening of incumbent ideology in the Middle East

Regional leaders are clearly experiencing a hardening of traditional ideologies in response to the crisis which could lead them to believe that mass violence is the only viable tool available to achieve their goals.

One of the ideologies on the table that could be coming rapidly to the fore given Israel’s military expansionism into a three-front regional war is a longstanding nexus of Israeli military and strategic thinking that dovetails closely with the Washington neoconservative ideology that helped drive the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

This is reflected in the 1996 report, A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm, produced by a research group chaired by incoming Bush administration advisor Richard Perle at the Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies in Washington DC. The report, prepared at the time to advise Netanyahu, appears to have hugely influenced the thinking of the Israeli right-wing and US national security officials. A Clean Break was also reportedly shaped by a previous paper by former senior Israeli Foreign Ministry official Oded Yinon.

Together, these documents imply that the US should support Israel in embarking on an aggressive strategy to reshape the entire Middle East, involving the occupation of the West Bank and Golan Heights, the encirclement of Gaza, the invasion of Lebanon, the dismemberment of Iraq and Syria, and the destabilisation of Iran. With Israel now opening up war on three fronts, it is plausible that this dangerous ideological vision has been given a new lease of life.

Unfortunately, of course, this is not a plan that can ‘work’ in any meaningful sense. Any attack on Iran is at risk of leading to an escalation with deeply unpredictable consequences that, nevertheless, includes a range of catastrophic scenarios.

So far, Western national security officials – stuck within siloed incumbent OS frameworks of analysis – are focused on examining military risks largely in isolation from systemic interactions with other sectors. For instance, while President Biden has publicly condemned the idea of an Israeli strike on Iranian nuclear facilities, he has signalled potential approval of the targeting of Iran’s oil facilities.

In reality, any attack on Iran which results in the destruction of significant infrastructure – especially one aimed at inflicting significant economic damage through destruction of economic assets central to Iran’s economy (already straining under international sanctions) – is likely to prompt another counterstrike from Iran on Israel. This in turn would necessitate further counterstrikes from Israel, potentially driving an escalating crescendo of escalating military actions that could rapidly culminate in full spectrum conventional warfare.

If Iran believes that it is being pushed into significant danger – and especially if it believes that it is being targeted in an attack designed to fundamentally destabilise the existing government – this existential fear could prompt Iran to believe it no longer has much to lose. Internal opposition to the government would be quickly neutralised in mass public support for anti-Israel response, boosting support for hardline Islamist ideology. In this case, the mutual radicalisation of the conflict could lead to actions with seismic global systemic consequences.

The road to global system paralysis

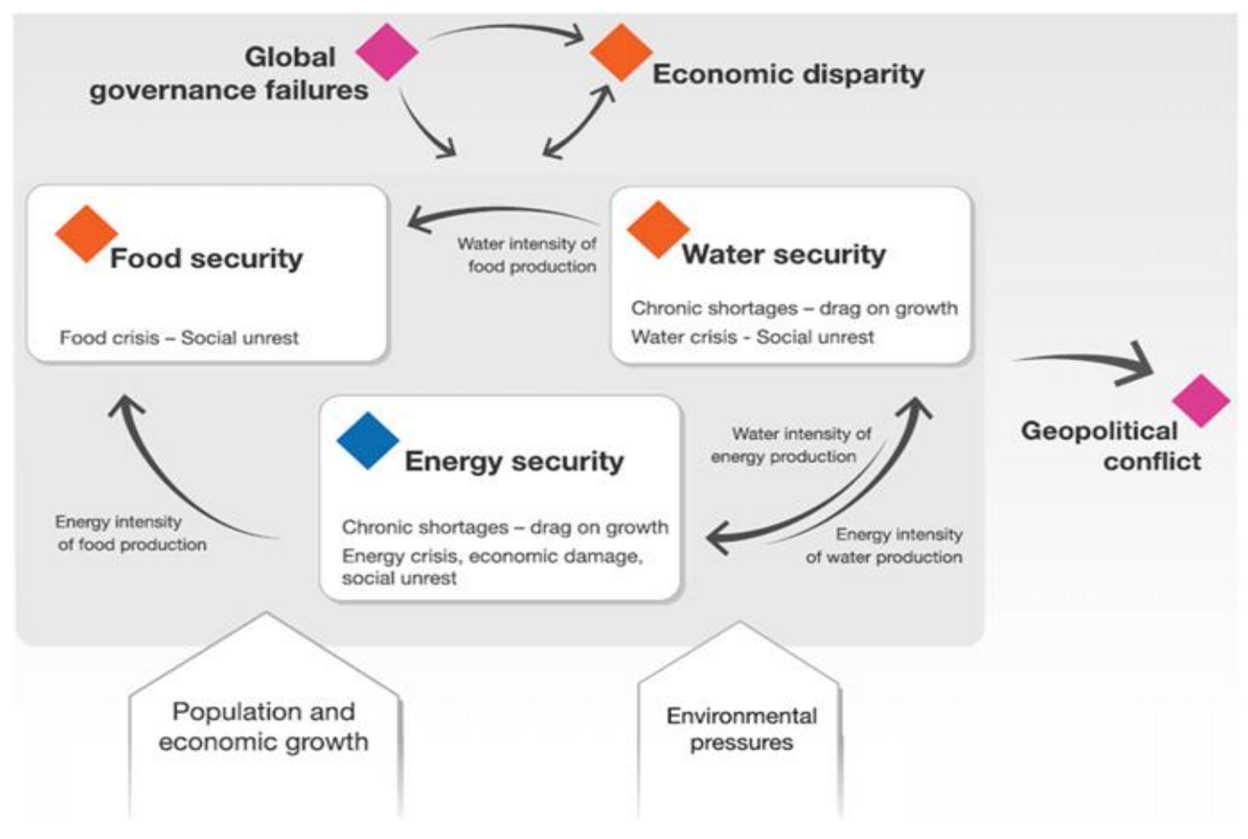

Any escalation of the conflict would lead already exorbitantly high oil prices to spike. Permanently high oil prices – triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – have already triggered rampant inflation, a global cost of living crisis, and slow economic growth while pushing many economies into recession. Any significant regional conflict between Israel and Iran will drive prolonged oil price spikes with destabilising global economic consequences.

Such consequences could be sufficient to significantly derail economic recovery, which would potentially undermine the precarious political stability of numerous governments already facing high rates of polarisation, unrest and internal chaos.

This scenario could be further radicalised if Iran resorts to blocking the Strait of Hormuz, through which up to 30% of the world’s oil is shipped. If Iran believes a regime-change scenario is on the cards, the idea of disrupting global oil shipping through the Strait, potentially with the backing of Russia and China, would suddenly seem a 'reasonable' response.

Any US effort to counter such actions would not be straightforward, but could therefore easily result in a protracted and wider conflict pulling in superpower competition. The more dangerous consequences would be on the global financial system. A shutdown of the Strait of Hormuz would have catastrophic consequences by shutting out huge volumes of oil – currently still the life-blood of the global economy.

Price spikes and global energy shortages would hike up inflation to incendiary levels, triggering global economic recession at the least, and if prolonged likely precipitating global financial collapse. Major industrial systems – from manufacturing to food production to transportation – would potentially face breakdown. Economic repercussions on oil-producing nations including the United States and other Middle East powers would be severe by slashing oil revenues, leading to potential social unrest. Oil-import dependent countries would similarly find key industries grinding to a halt without sufficient supplies of affordable energy.

War with Iran could trigger synchronous failure

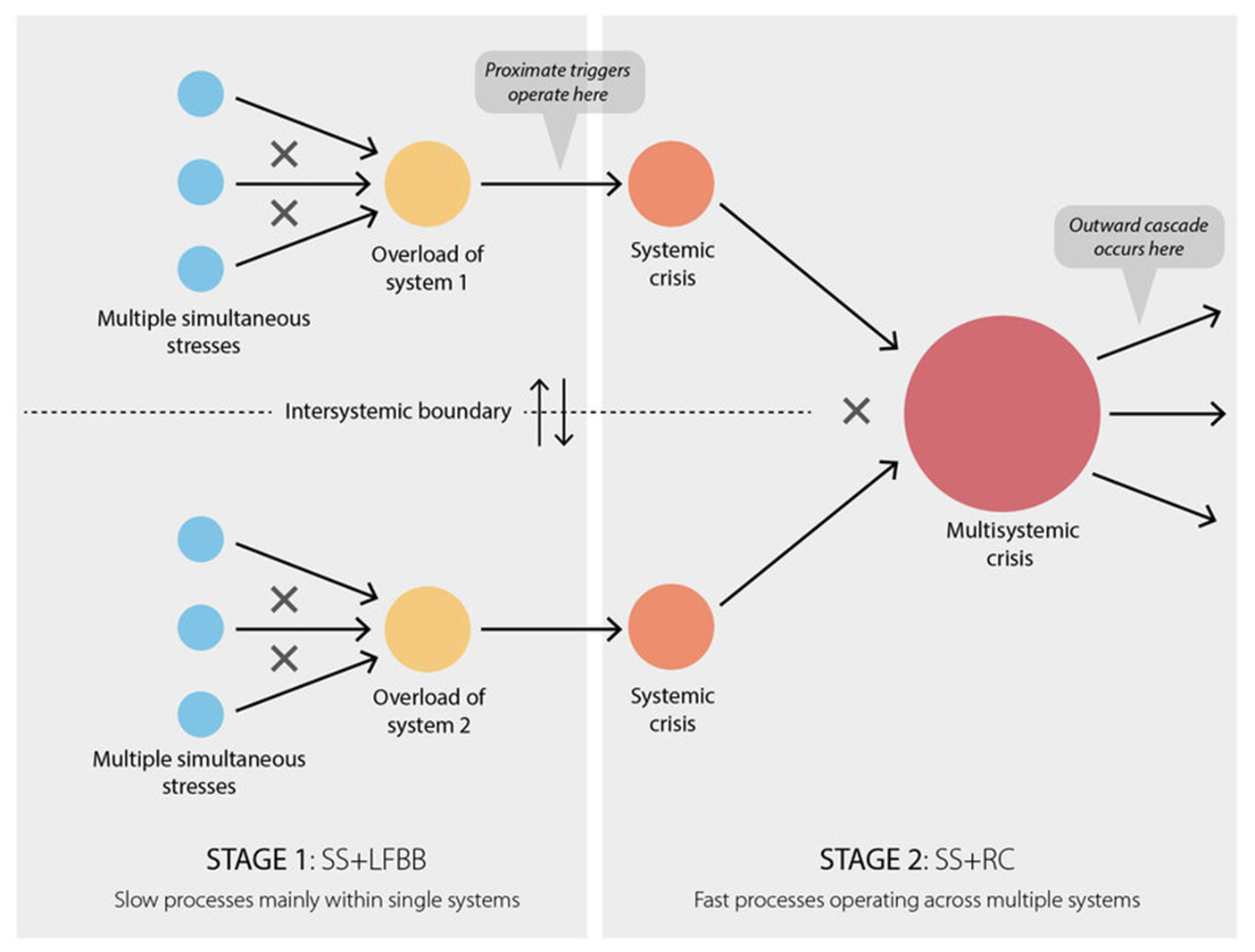

A pioneering systems theorist who is now heading up the Cascade Institute in Canada, Professor Thomas Homer-Dixon, has coined a name for this type of complex systemic crisis: “synchronous failure”.

Synchronous failure happens when multiple systems fail at the same time. Such a failure can lead to systemic collapse because its scale overwhelms the capacity of institutions within it – evolved to grapple with issues on a siloed basis – to respond effectively.

The risk of global synchronous failure is already increasing due to many converging factors – the global decline of EROI, the intensification of climate change and concomitant environmental disasters, the increasing unsustainability of industrial food production, the widening polarisation between and within cultures and communities, the dangers of unregulated artificial intelligence and untamed disinformation – to name just a few.

Planetary phase shift theory tells us that these are not, however, merely ‘converging factors’, but inherently interconnected symptoms of human civilisation rapidly moving out of equilibrium with earth systems.

As this has happened, the efficacy of both prevailing industrial era technological-material systems and organisational-cultural systems is declining. These systems cannot respond to the complexity of our current moment. They do not understand it. As they are therefore becoming increasingly disrupted, the resulting political destabilisation is focusing the political sphere on how they can shore-up a system already in freefall (and, of course, they are in total denial that the system is failing).

This creates an overarching global dynamic: earth system crises destabilise the global system, leading to various shocks – whether economic, political, environmental or otherwise (or all). Our political institutions for the most part don’t recognise these systemically. Focusing on the symptoms, and as the resulting crises drive social polarisation, they tend to blame surface symptoms which tends to result in Otherisation and group demonisation.

Exclusionary forces then tend to focus thinking and action on old paradigm ideological constructs often around markers of physical identity – territory, profits, the nation, sexuality, and so on – a process that afflicts both left and right in different ways. Instead of responding to the systemic crisis, our response simply contributes to destabilising the system even more. We find ourselves caught in a global amplifying feedback loop of systemic failure.

As we move through the release stage, the danger is that these unleashing energies generate so much chaos that they destabilise and at worst destroy our capacity to continue moving through the fourth reorganisation stage, necessary for civilisation to transform sufficiently to give rise to a new life-cycle for humanity. We could end up derailing our capacity to accelerate the transformation of energy, transport, food and information systems, and the associated transformation of our organising systems, before they can reach fruition. A worst-case scenario would be that a regional conflict has major ramifications that degrade our civilisational capability to get to the next life-cycle.

There are, of course, other scenarios. One would be that, somehow, an all-out-war is still avoided. That's not enough to get us to the other side, of course, but buys us time to wake ourselves up to the gravity of our predicament, as well as the tremendous nature of the transformative possibilities before us. Yet as long as the regional crisis continues in this direction it's currently in, the risks of escalation and extremist polarisation are intolerably high.

That is where we are right now. These planetary and global-scale processes, I believe, are being refracted locally in different ways. Given the historical volatility of the Middle East, it is not surprising that the most dangerous dynamics for the global system are unfolding here.

In this context, observations by ecological economist Professor Julia Steinberger at the University of Lausanne are highly relevant. Last year, she noted the following:

Gaza is a blueprint for all of us this century. This is what the first real signal of this new century looks like, out in the open, clear for all to see… It is not just the knowledge of deliberate mass death and atrocities being committed: it is the realisation that our goverments are brazenly, proudly, supporting it… this feels like the multiple walls of hegemony closing in: military and police force, propaganda, economic and cultural spheres all aligned, with little to no political opposition, except on the very margins… And the lesson here is clear for all: if you are undesirable by any force within this hegemony, you will be brutally erased from the face of the earth, swiftly, without a murmur of protest or a hint of recourse… At every stage, the circle of unpersons will become larger, and the pressure to conform to the hegemon more intense.

The Middle East crisis, then, has become a crucible of the global system’s movement into the release stage, a microcosm of a dangerous ideological bifurcation process in which the obsolescence of the prevailing order is opening up a global process of Otherisation, manifesting in different ways in different regions.

Apart from the colossal scale of death and destruction, the huge impact on people and nations, the loss of life and mourning of loved ones, the next major risk is that the Middle East crisis becomes a vortex that blinds us from recognising where we are situated as a species...

That as we move deeper into the release stage, the breakdown of the prevailing order simultaneously opens up outsized possibilities for change and transformation that previously did not exist. Those emerging possibilities, as we’ve noted at length here at AoT, are pointing the way to a new type of civilisation, a system that works for the benefit of all in ways that our ancestors could never have dreamed of. We are on the cusp of the final stage in our civilisation’s life-cycle, a great reorganisation that could usher us into a new life-cycle in a new paradigm.

That is why we need to work toward widening public understanding of events like the Middle East crisis through the systems lens of the planetary phase shift. Because, floundering in the darkness of anger and war, we cannot reach for a possibility we do not know exists.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In