The US military has a sexual assault problem. But internal documents obtained under Freedom of Information reveal that Hollywood has worked closely with the Pentagon to conceal the extent of the problem from public awareness.

The latest statistics show that the number of military sexual assaults rose 38% overall — and 50% for women — between 2016 and 2018, to over 20,000 a year. Only a third of these were formally reported, with 43% of women who did report sex crimes against them saying they had a negative experience as a result. 90% of these crimes were perpetrated by fellow service members, usually of slightly higher rank than their victims. For junior enlisted women — the most-targeted category of all — 1 in 8 suffered an assault.

Beyond the statistics, I have spoken to several current and former employees of the US armed forces (both male and female) who have all said that the problem is endemic, and the response systems are profoundly inadequate.

The Pentagon’s official position on this is blanket denial. The military, we are told, is doing ‘everything possible’ to combat this ugly subculture within their ranks, ranging from posters to social media marketing campaigns. More recently this has included getting the Army-funded Institute for Creative Technologies to develop video game-like training tools to teach their employees how best to respond to SHARP (Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention) incidents. Yet these efforts strike many victims as little more than PR to make it appear that the military are doing something about the problem.

But official documents I’ve gathered over the last five years show that the Pentagon’s approach to dealing with sex crimes has focused overwhelmingly on treating it as a PR crisis.

The documents uncover the extraordinary role that the Pentagon’s entertainment liaison offices have played in downplaying sexism and sex crimes in the military. They reveal how Pentagon officials have long manipulated Hollywood to generate propaganda making it look like the Department of Defense (DOD) is dealing with these crimes, when in reality victims consistently say support systems and investigations have failed them.

This exclusive report throws new light on how a large range of major Hollywood films spanning several decades — all the way from Top Gun to Pitch Perfect 3 — have served to suppress and deny the Pentagon’s sex-crime problem.

Sex Crimes: A Pentagon PR Concern

Sexism and sex crimes by members of the military has been a PR concern for the Pentagon for decades before the documentary The Invisible War helped make it a widely-recognised media topic.

The Pentagon’s Hollywood database includes a small number of films that were neither granted nor denied military support, because the film-makers never asked the DOD for help. One such film — 1989’s Casualties of War — is based on the real-life kidnap, rape and murder of Phan Thi Mao, a young Vietnamese woman, in 1966. This hideous crime was committed by a US Army squad, one member of which refused to take part and subsequently blew the whistle. The database describes Casualties of War as:

Combat film which captures a popular view of the nature of the American experience in Vietnam. Squad sent on recon mission kidnaps Vietnamese girl, rape her, and ultimately kill her. Based on true story which appeared first in the New Yorker and then in book form. The one soldier who did not take part in sexual abuse reported what happened and men were court martialed and sentenced to prison but did not serve time. “Hero” portrayed as villain for reporting crime.

That the Pentagon included this film in their limited database demonstrates that stories like this are a worry for them. This database category also includes 1999’s The General’s Daughter, where the document says:

Murder mystery about who killed daughter of a politically ambitious general who tries to suppress evidence. Negative scenes include USMA cadet daughter raped by fellow cadets and compliance by officers in cover up.

The database entry shows that the Pentagon actively keeps an eye on Hollywood’s output for any film containing such ‘negative scenes’.

This routine policing of Hollywood led to the Army changing the name of Ewan McGregor’s character in Black Hawk Down (2001) because the real soldier was serving a 30-year sentence for rape and child molestation. His ex-wife commented:

They are going to make millions off this film in which my ex-husband is portrayed as an All-American hero when the truth is he is not.

Likewise in 2005 the Pentagon refused to help with a French documentary project called Army Rapists, and in 2011 they turned down the documentary Women at War because ‘the angle of the production deals with sexual harassment & PTSD.’ As a result Women at War was never made. While the similar documentary Uniform Betrayal: Rape in the Military was produced, the Army refused the film-maker’s requests for interviews.

The Pentagon’s Conservative Outlook on Sex

A more comprehensive look at the Pentagon’s values around sexual relationships shows they consistently take a conservative, some would say repressively moralising view. They rejected Independence Day (1996) in part because they felt Will Smith wasn’t a good representative of the military as he was dating a stripper — but these values go back several decades in the entertainment liaison office.

When it came to Vietnam war films, a repeated issue concerned the wives of prisoners of war (POWs) or troops who were missing in action (MIA) seeking solace in the arms of another man. 1972’s Limbo was denied Navy support because:

It showed POW wives being unfaithful and completed film would be shown in North Vietnam as soon as it was released in US. And the wives’ infidelity would hurt POW morale, especially if film had received military support.

Five years later the Air Force turned down Rolling Thunder because the script contained an ‘unfaithful wife’. The following year Coming Home was also denied, in part because of a plotline about a deployed soldier’s wife who falls in love with another man.

In 1991’s Flight of the Intruder one of the characters gets involved with the wife of a pilot who is MIA and they fall in love, which the military’s script notes say ‘may be considered a happy ending.’ The Navy objected to this storyline, saying that it suggested:

MIA wives are vulnerable, easy prey and available for the asking. This was not always the case and the endings are not always happy.

This was changed so the affair is with a woman whose husband was killed in Vietnam, to sidestep any question of infidelity.

These values lasted well into the 2000s. When the makers of Wife Swap approached the Army in 2004, one report says:

Yeah. My reaction, too. Relatively politely declined the offer from the producer of this hit ABC show (the networks #3 show in all markets) to feature an Army wife (either the wife of a Soldier or a wife who happens to be a Soldier herself) “swapped” with the wife of a civilian family.

Incredulous, I inquired that even if I could possibly reconcile the concept of Army Soldiers or Army wives being “swapped,” with all the ’60s era connotations that implies, to what sort of family would the wife go?

The producer let it slip that it would have to be to a family that would create “good TV, you know, a progressively minded family” and then I was treated to this producers bent on how she believes most members of the Army must think and behave and how good that would be to show that compared to “a family who doesn’t necessarily believe everything they are told”.

Sex and Sexism in the Forces

Aside from unfaithful wives another consistent problem for the DOD is romantic and sexual relationships between service members, especially those of different ranks. The military’s rules on fraternization are extremely broad, in some ways forbidding even friendships between troops. For a long time the military’s Hollywood offices also tried to cover up sexism in the military, while simultaneously adopting sexist attitudes themselves.

This is reflected in the DOD entertainment liaison offices’ approach to requests for production assistance, and in script changes they forced onto productions.

In 1988, the short-lived TV series Supercarrier was denied military support because there was ‘Too much fraternization and too many sexist comments’ in the script. A letter in the military file on the series comments ‘Thank God!’ when the show was cancelled after just 8 episodes. There were similar problems on the 1990s TV series The Cape.

Also in 1988 the producers of Biloxi Blues requested copies of Army training films, for a scene where Army characters are sat watching them. A comment in a DOD memo says that the ‘Army does not want certain sex/VD films used’ so they weren’t provided to the film-makers. They also changed dialogue where one Army character ‘refers to himself as a homosexual’.

While the sensitivity over sex in the forces still remains, when it came to sexism at the DOD things began to change a little in the 1990s, as women started to be allowed to fly combat missions and take on other key combat roles. But that was too late for Firebirds a.k.a. Wings of the Apache (1990) where the Army had some problems with the character of Terry — a female Army pilot.

In particular the DOD didn’t like her referring to ‘her career’ and insisted the script include lines where she expressed her desire to be ‘part of the team’. Also, she flies a combat mission during the film — unlike real women in the real Army at the time — so the Army told the producers to add in a line making it clear she was only flying the mission ‘due to circumstances’.

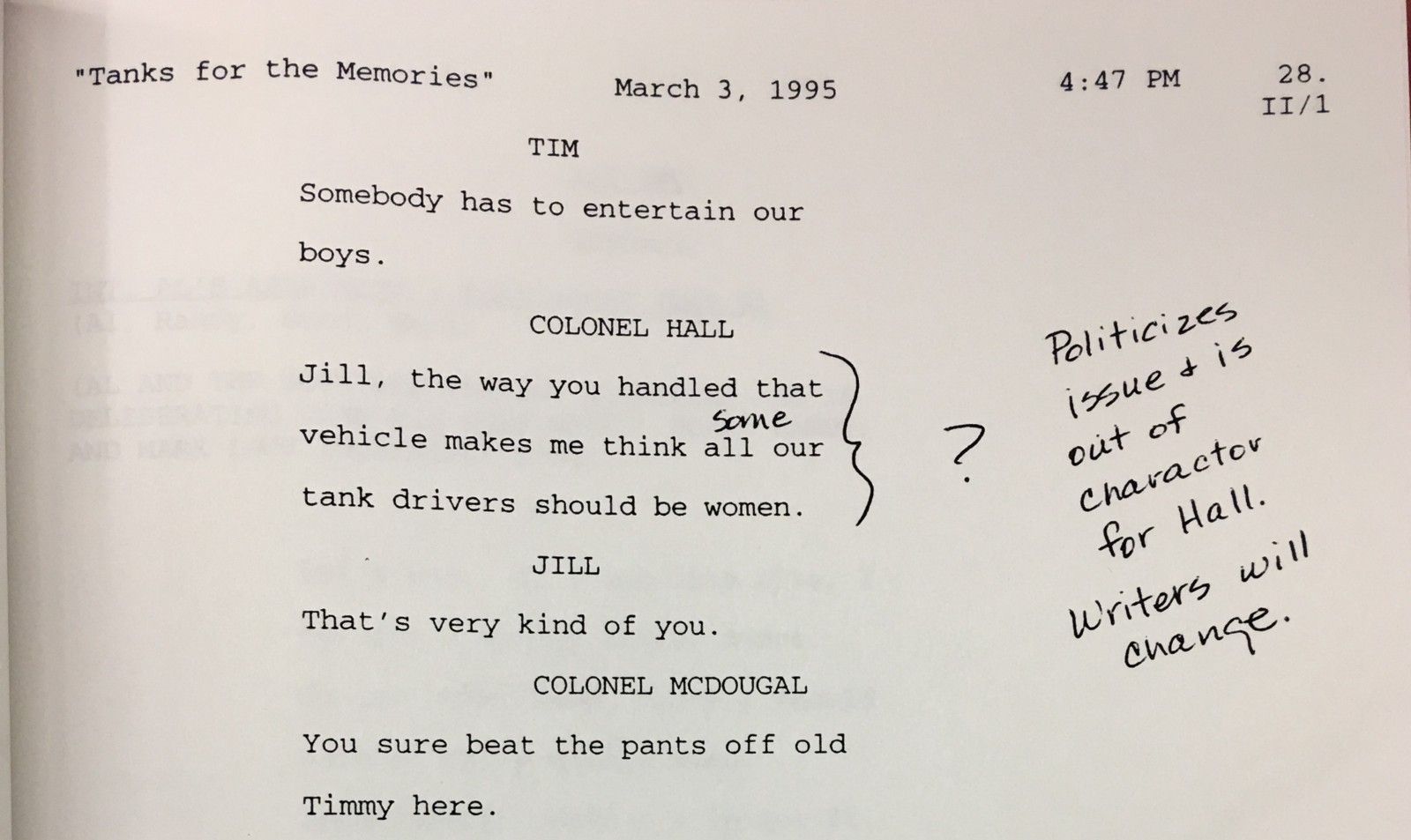

Similarly, on an episode of Home Improvement titled ‘Tanks for the Memories’ Tim and his wife Jill visit a Marine Corps base and get to drive some tanks on the training track, with Jill proving much more adept at manoeuvring the vehicle than Tim. Afterwards, in the canteen, the original script had a Marine officer saying ‘maybe all our tank drivers should be women’. A handwritten note on the draft script says that this ‘politicizes the issue’ and that ‘writers will change’. The line does not appear in the finished episode.

This ambiguous shift in attitudes was demonstrated again when Marine veteran and former Secretary of the Navy James Webb approached the DOD in 1993 about support for adapting his novel Fields of Fire, based on his experiences in Vietnam. Webb was turned down because when the military reviewed his script they found numerous problems with it. These included a scene where a Marine masturbates, as well as ‘references to promiscuous behaviour and venereal disease’.

The Navy also flagged up ‘A variety of sexual references that, again, may reflect the reality of the times but that conflict with current policies regarding sexual conduct.’ Even though the film was set 20 years earlier, the DOD’s new policies were at odds with some of the dialogue, so despite the script’s accuracy they saw this as negative PR. As a result of the DOD’s refusal Fields of Fire was never made into a film. Their inability to be honest about their own past led to them effectively censoring this movie out of existence.

Webb also wrote the screenplay for Rules of Engagement (2000) which did win full DOD support after an extensive rewriting process. One of the ‘problematic’ scenes was where Major Hodges (Tommy Lee Jones) dances with a female Colonel at his retirement party. The Marine Corps’ script notes comment:

Majors in the Marine Corps do not conduct themselves as “Flirtatious and/or funny” when dealing with superiors. No Colonel for that matter is going to be seen dancing cheek to cheek with a Major. Suggestion: make Sarah Grant a civilian secretary or paralegal on Hodges’ staff or, make her a lieutenant colonel who has been selected for colonel. If she remains military, though, the flirting should be toned way down.

In the end, this character was removed from the film. Rather than give this female military character (at that time still quite a rarety in entertainment) something more to do than be an object of romantic interest, they simply eliminated her from the story. In trying to cover up for sex and sexism in the military the DOD and the film-makers doubled down on their sexism.

Top Gun and Tailhook

This conservative approach backfired horribly when it came to Top Gun — the film that the DOD said ‘rehabilitated the military’s image, which had been savaged by the Vietnam war.’

The film centres around the romantic relationship between a top-notch Navy pilot (Tom Cruise) and a civilian evaluator at the Navy’s elite pilot academy (Kelly McGillis). This includes a highly questionable scene where Cruise follows McGillis into the bathroom at a bar and propositions her, only minutes after they first meet.

But the Navy didn’t have any problem with that scene, as long as the McGillis character wasn’t in uniform. During the script negotiations the producers considered making her a Naval Officer but were told not to do this ‘because of the inordinate sensitivity to the relationships in the service between male and female personnel. This will impinge primarily on the scenes which connote the sexual relationship, romantic developments, etc.’

Another script note highlighted dialogue references to ‘two sets of sisters’ and ‘virgins’ that in the Navy’s view ‘indicate attitudinal characteristics that if overdone become objectionable’. These lines were removed and do not appear in the film.

Once the script had been rewritten to accommodate the Navy’s concerns the Pentagon provided support on an enormous scale, resulting in over $1.1 million dollars of reimbursements to the DOD (typically movies from this period paid $100,000–200,000 for military assistance). Top Gun was a huge success for both the film-makers and the DOD, so Jerry Bruckheimer and the rest began developing a sequel.

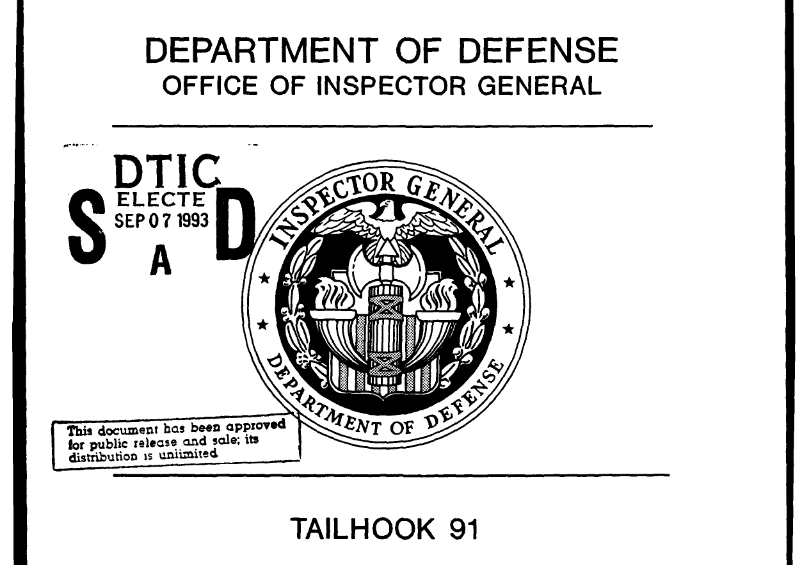

Then, in September 1991 at the annual Tailhook Symposium at the Las Vegas Hilton, over 100 Marine and Navy aviators sexually harassed and assaulted 83 women and 7 men. This included forcing women to ‘walk the gauntlet’, whereby dozens of aviators lined the hallways of the 3rd floor of the hotel, forcing women to walk between them to get to their rooms. As the women passed they were subjected to gropes and sexual assaults from the mob.

The scandal resulting from the Tailhook events provoked a large scale Naval Investigative Service inquiry, and then a report from the DOD’s Inspector General. Over 300 Navy officers including 14 admirals faced consequences either for covering up what had happened or for encouraging it, many of them being forced out of the Navy. This met with criticism from former secretaries of the Navy including James Webb and John Lehman, who defended the Navy and blamed ‘political correctness’.

The scandal also meant that the Navy withdrew all support for Top Gun 2, purportedly on the grounds that scenes in the original film had encouraged the behaviour seen at the Tailhook Symposium. The film was scrapped, and it would be another 20 years before the project was revived. Again, due to the DOD’s inability to face their demons they prevented a movie from being made.

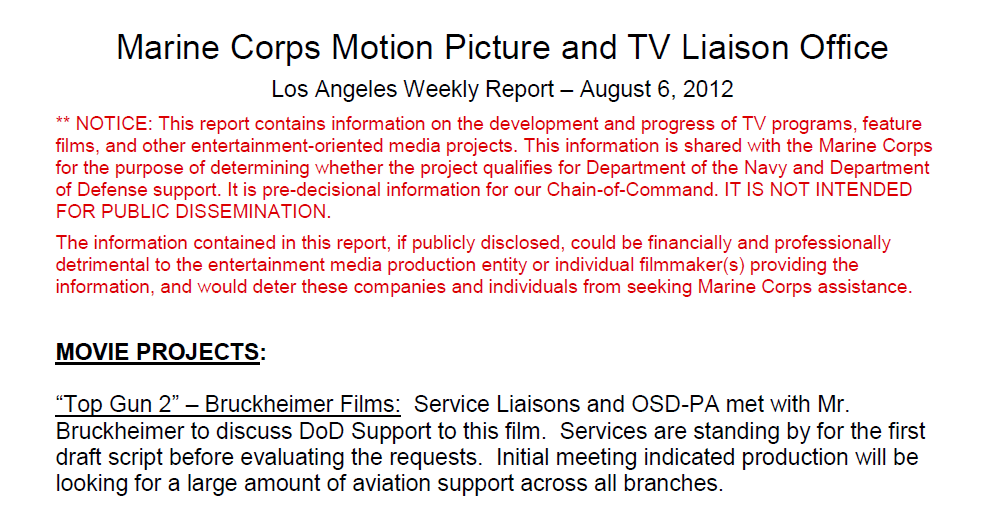

But Top Gun fans needn’t worry too much — as detailed in a 2012 report from the Marine Corps entertainment liaison office, Bruckheimer approached the military before even the first draft script for Top Gun: Maverick had been written. He was ‘looking for a large amount of aviation support across all branches.’ The film will be released in 2020.

G.I. Jane

The 1990s also saw the rather clumsy effort to discuss women’s progress in the military that was G.I. Jane(1997). The plot features an ambitious senator who tries to raise her profile by taking up the cause of women in the military and demanding a series of ‘test cases’ whereby women are put through elite special forces training. Jordan O’Neill (Demi Moore) is chosen to undergo a fictional Navy special warfare training similar to that undertaken by real-life Navy SEALs.

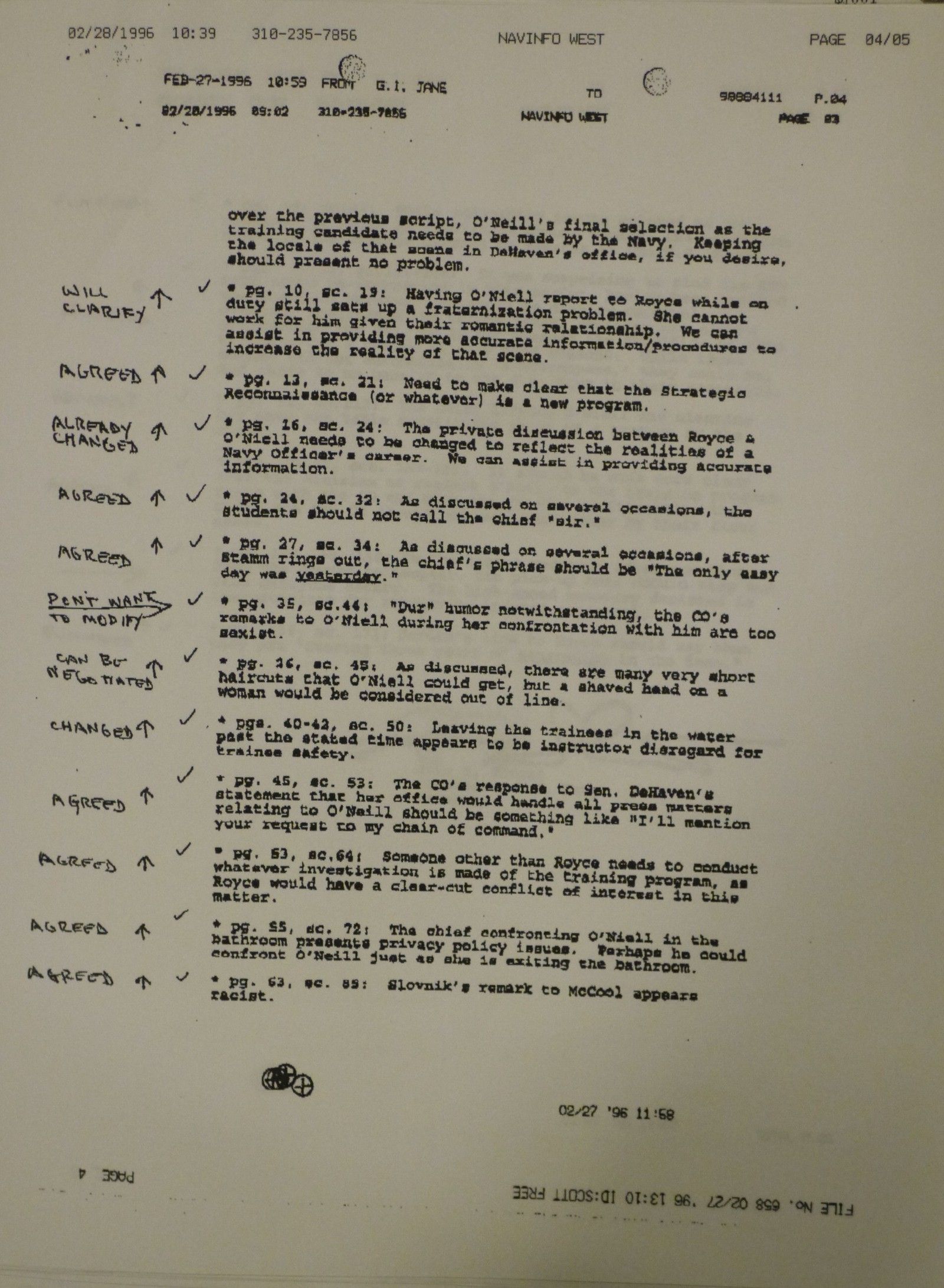

Ridley Scott approached the DOD in early 1996 to ask for production assistance, but negotiations broke down over the script and ultimately the film was made without military support. While it was reported at the time that the Navy objected to the whole concept of a female SEAL, the documents tell a different story.

The script notes list dozens of problems, including that O’Neill had a boyfriend in the military, who in the original script was her boss. Scott’s handwritten comment on the script notes says ‘will clarify’.

On another scene the Navy said:

“Dur” humour notwithstanding, the CO’s remarks to O’Neill during her confrontation with him are too sexist.

Scott responded, ‘Don’t want to modify’. Another issue was a scene where Moore shaves her own head. The script notes observe:

As discussed, there are many very short haircuts that O’Neill could get, but a shaved head on a woman would be considered out of line.

Scott’s comment says ‘can be negotiated’. One other problematic element was a scene where a SEAL urinates in a foxhole in front of O’Neill. The script notes say:

While addressing issues related to the presence of women in front-line ground combat, the urination scene in the foxhole carries no benefit to the US Navy.

Other problems were some ‘racist remarks’ and in particular the sequence where the Master Chief confronts O’Neill while she is naked and in the shower.

Scott agreed to most of these changes, including removing the shower scene, but it wasn’t enough for the DOD. They wanted to tell a story about a woman in the military’s elite, without actually including any scenes about sexist challenges faced by women in the military. Scott stood firm and refused to make some of the changes demanded by the Navy’s Hollywood office, so they rejected his request for support.

Interestingly, Scott went back to his original script once the Navy turned him down, including putting the shower scene back in. Sadly, it comes across as unnecessary and exploitative, albeit a somewhat realistic depiction of military sexism.

The Invisible War

Fast-forward to 2012 and finally we got a major American documentary that takes an unvarnished, uncensored look at the problem of military sexual assaults and military sexual trauma. Indeed, the fact that the experience is so common that we have the phrase ‘military sexual trauma’ should tell you how rife the problem is.

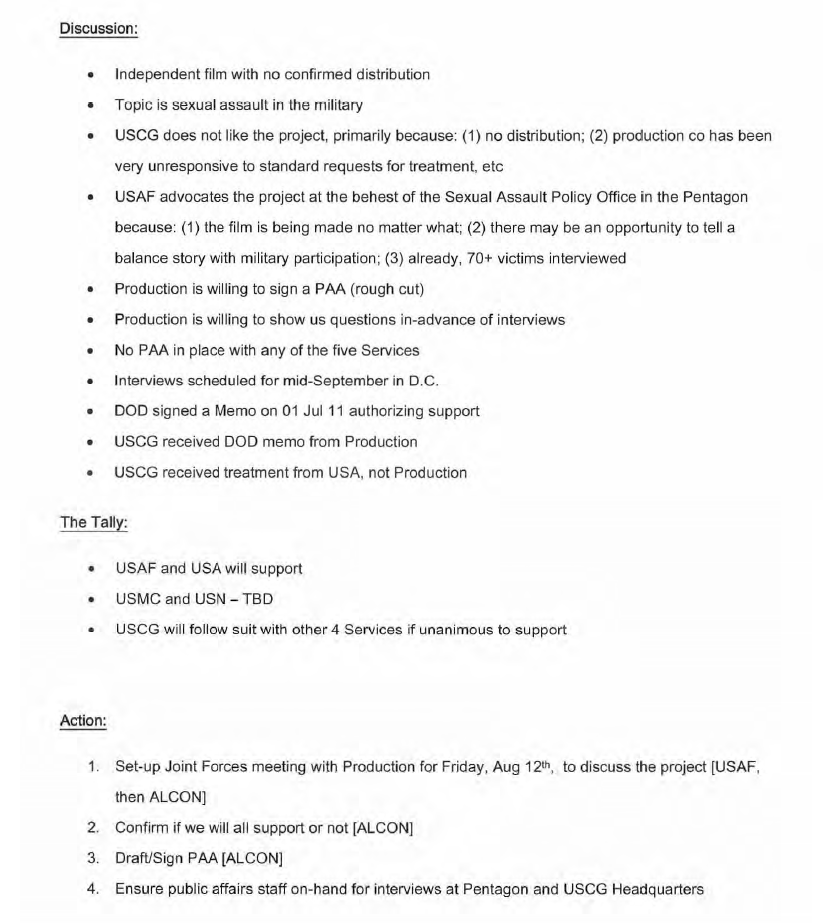

The Invisible War is a gut-wrenching, heartbreaking account of both women and men who were raped while serving in the US military, and of the consequences they faced if they spoke up about it. The film-makers asked for military support in order to interview officials in charge of the various branches’ sexual assault programs, but refused to provide the film treatment for the military to review. They stood up to the entertainment liaison offices, who backed down, reasoning that the film would be made regardless so participating was the only way to try to ensure they got their message across.

This was laid out at a meeting in August 2011, ahead of the requested interviews the following month. Representatives from the entertainment liaison offices of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and the Coast Guard met, along with Phil Strub from the DOD. The minutes of this meeting were obtained by Muckrock and outline the logic behind the military’s involvement in the film.

An Air Force review of their participation says ‘the original objective and hope was to try and interject into the film that was already in production and try to provide some balance to the story.’ The Army’s assessment echoes this, saying ‘The documentary will benefit from Army input; resulting in a greater balance to how the issue is presented publicly.’

Unfortunately, ‘balance’ in this case really meant downplaying the extent of a real problem. The Coast Guard were the first to be interviewed, and immediately produced an after-action report to send round and help prepare the other branches of the DOD for their interviews. They also drew up extensive Public Affairs Guidance on the documentary, including responses to questions they were likely to face from journalists.

When The Invisible War came out the military went into overdrive: setting up google alerts on the topic of military sexual assault, monitoring news coverage and reviews of the film and even keeping an eye on what people were saying on the movie’s facebook page. Internal emails show that rather than respond to the documentary by making changes to their sexual assault support and investigation systems, they saw the film as an attack on the military, closed ranks, and sunk into denial.

One Navy email from 2012, sent the day the movie was released in the US, records how the film’s facebook page already had thousands of likes, before commenting ‘After seeing the comments and data on the page, I immediately wanted to ‘unlike’ the page.’ An Army email on the film itself said ‘I saw it once — that was enough.’

The military’s frustrations with The Invisible War even extended to complaining about the DVD copy provided to them by the producers. Emails from the Army’s entertainment liaison office complained that it had ‘some sort of funky encryption’ that stopped the disc playing ‘while the DVD figured out whether it was a legal copy’. One email adds ‘They’ve made this difficult every step of the way.’

But the prize for the most grotesquely insensitive and stupid response to The Invisible War goes to Lt Luke Peterson, an attorney at the Coast Guard who was delighted to have found a critical review of the film. He joyously sent it round to his colleagues, saying, ‘I was happy to see this post that was critical of the film and takes the time to question the accuracy and motives of the filmmakers.’ In another email he commented:

It really highlights some of the problems with this film. If only we could get the mass media to carry such an article, we could start to work on addressing the real problems instead of responding to falsehoods.

How the Pentagon Uses TV to Cover Up their Sexual Assault Problem

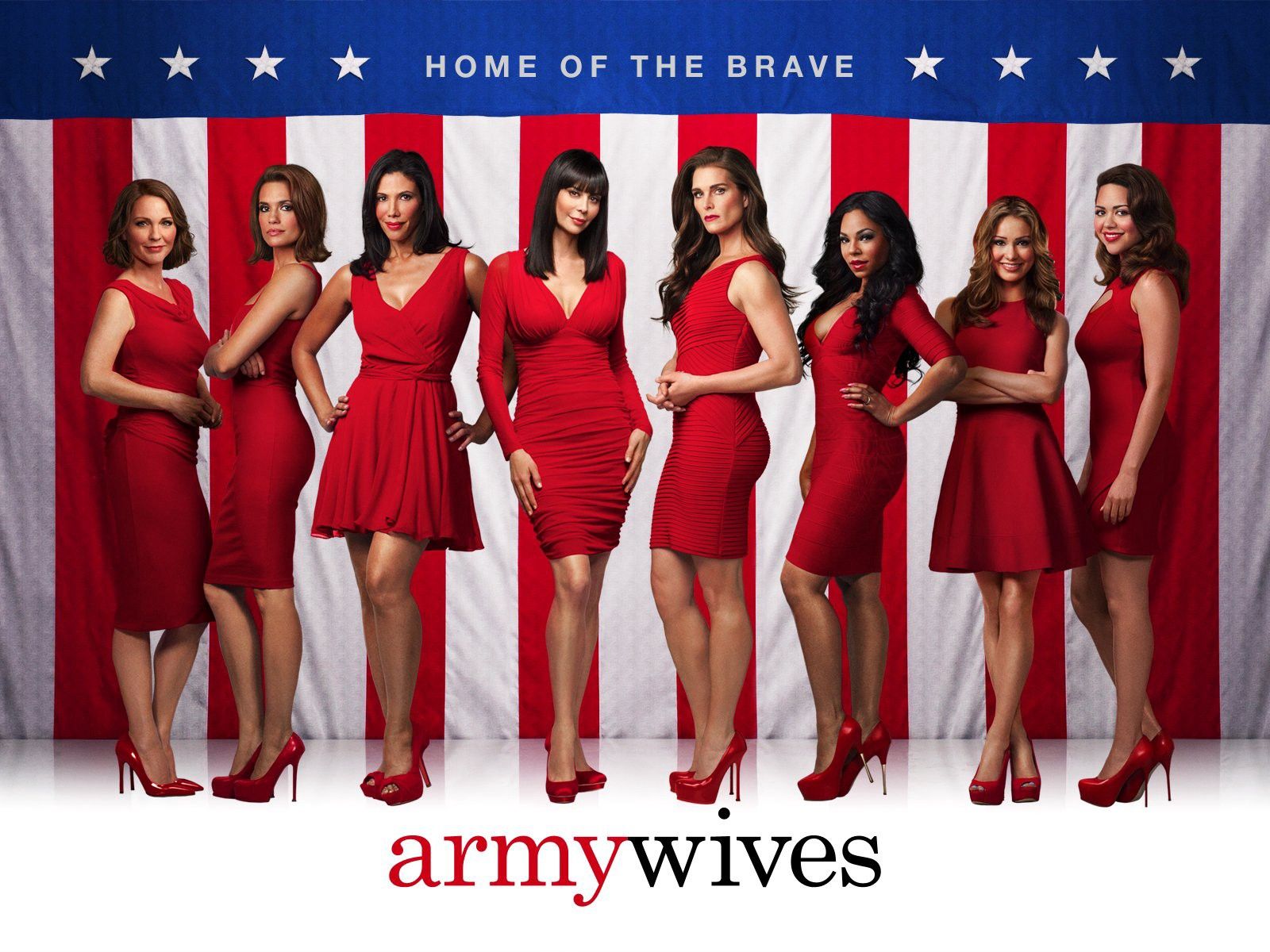

At the same time that The Invisible War was being developed the Army were hard at work helping to write an episode of Army Wives about military sexual assault that sent a very different message. A March 2011 report says:

█████ is working with writers to develop story line involving the sexual assault of a female soldier while deployed. █████ is working to include SARC [Sexual Assault Response Coordinator] involvement and restricted/unrestricted reporting as part of storyline.

By the end of March the storyline had been firmed up, and the Army and DOD were keeping close tabs on its development.

Episode 510 deals with the sexual assault of a female soldier while deployed who eventually becomes homeless as a result of the PTSD she suffers from due to the attack. Female Soldier was a pilot. ███████ is aware of the subject matter and has notified appropriate channels.

The finished episode depicts a homeless Army veteran who gets into trouble for assaulting a man at a shelter. Lawyers investigating the case realise she has PTSD, and eventually the veteran reveals she was raped while deployed to Iraq, by a fellow soldier, resulting in her leaving the Army. While the lawyers succeed in getting the charges against her dropped and she begins counselling, the rapist gets away with his crime due to a lack of evidence. While the Army looks sensitive and caring, the system still fails the female soldier, though this is brushed off due to the rapist having subsequently died in a motorcycle accident.

A later entry on Army Wives illustrates why the US Army review the scripts and provide support on almost every episode of the series. It notes:

This show continues to have a weekly audience well over 4 million, specifically targeting centers of influence in the 25–50 year old female demographic.

This cuts to the heart of a disturbing trend in the entertainment liaison offices — they are seeking to boost female recruitment, but are doing nothing to advocate for justice when a large minority of those female recruits are sexually assaulted.

These screwed up priorities were again in evidence in 2013 when, apparently in response to The Invisible War, the Navy:

Submitted request to NCIS production staff for site visit and meeting with Prod Execs/Writers to discuss future episodes demonstrating NCIS [in service of] sexual assault investigations and adjudication.

In an unusual move the Navy’s entertainment liaison office actually pitched the idea to the producers, they didn’t wait for a relevant script to come in. A dozen episodes later and the writers of NCIS delivered:

Episode #255 thematic depicts a service member(s) sexual assault. NAVINFOWEST Project Officer will forward to SAPRO for consultation and input recommendation to ensure victim advocacy and reporting are accurately depicted in the script.

After the Navy and SAPRO’s script review they asked the writers to make changes to promote the idea that if you are sexually assaulted in the Navy then your fellow sailors will stand up for you:

[S]eries producers/writers successfully incorporated script rewrites that demonstrated Sailors helping Sailors seeking assistance and reporting sexual assaults. Current episode air date in April TBD will align with the DoD’s Sexual Awareness month.

As the Navy reports record, the episode was watched by some 16.73 million viewers and the episode was re-run just months later. In exchange for a minimum of support the producers wrote in the Navy’s desired messaging, which totally contradicts the grim reality.

A couple of years later in 2015 NCIS revisited this area and submitted a script ‘depicting negative portrayal of women integration on SSNs, sexual harassment by numerous crewmembers and ineffective leadership by the command Triad.’ Reflecting the realities portrayed in The Invisible War the sexual harassment was not dealt with properly by Navy command.

On September 2nd Phil Strub and the Director and Deputy Director of the Navy’s entertainment liaison office held a conference call with the series Executive Producer and the writer of the episode, to outline their concerns.

The following day the Executive Producer called back to say that they were reversing almost the entire storyline:

Executive Producer called to notify us that script #288 revision was in progress based on feedback provided. Episode #288 will now take place on a DDG and will depict Sailor by-stander intervention, perpetrator adjudication, and timely and effective engagement by the Triad.

Even though the Navy provided no production support on this episode the producers completely rewrote their script in keeping with the Navy’s PR objectives, showing them responding efficiently and sympathetically to sexual harassment.

How to Recruit More Women and Lie to Them About Sex Crimes

In recent years the DOD has increasingly sought to recruit more women, leading to their massive-scale support for films like Captain Marvel and Pitch Perfect 3. In Captain Marvel Brie Larson plays Carol Danvers — a US Air Force pilot-turned superhero. Set in the 1980s and 90s our protagonist is subject to sexist comments and cannot fly combat missions, but there is no hint of sex crimes being committed against her.

The Air Force had been working with the producers for over two years before its release. In 2017 co-directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck, along with producers from Marvel, went on a tour of US Space Command organised by the Air Force for a select group of Hollywood bigwigs. This led to Brie Larson visiting a US Air Force base and being taken for a flight in an F-16. She also spoke at length with Brig Gen Jeannie Leavitt to help develop her character. The Air Force were so happy with the finished product that they sent over a dozen of their people to the red carpet premiere of the film.

For Pitch Perfect 3 the Air Force made various changes to the script in exchange for access to planes and filming locations. Script notes from the Air Force and DOD show that they would only allow a line where one of the Bellas says her military father ‘practically killed Osama Bin Laden’ after they were reassured it was being played for laughs.

In particular the DOD encouraged the romance between one of the Bellas named Chloe and an Air Force officer named Chicago. In one scene between the two they wrote in dialogue where Chicago says the military is ‘like family’. In another scene where Chicago confronts Fat Amy’s father they ensured he was protective without being aggressive — ideal boyfriend material.

However, in an echo of their moral conservatism of earlier years they asked that a lesbian kiss between one of the Bellas and a female soldier be toned down because ‘they’re complete strangers’. In the event this scene was removed entirely and another line inserted where the (black lesbian) Bella says, ‘Now that gay people can serve in the military, I’m gonna join the Air Force, and let them pay for my flight school.’

The Pentagon’s dual propaganda purposes are clear — recruit more women, and deceive them about the high risk of them becoming victims of a sex crime while in the military. If anything, the changes on Pitch Perfect 3 show that they’re now trying to sell women on the idea that the military is a good place to meet a nice young man — the pitch perfect cover-up of their sex crime problem.

Given the Pentagon’s traditionally conservative outlook on sex it logically follows that they cannot confront their sexism and sex crime issues. They cannot even have an honest conversation about sex, especially sex between service members, so it is perhaps unsurprising that they cannot have an honest conversation about sexism and sex crimes in the military. By presenting military life in a sanitised, largely sexless way they consistently avoid the real issues faced by women and men in their employ. The Pentagon barely wants to admit that sex exists, let alone that sex can be a motivator for and a means of committing violent crimes.

On the rare occasion that they do support a production that discusses sexual harassment or assault, they pressure the producers into rewriting it to make it an advert for how the military are dealing with the problem. They reduce it to a PR concern, when it should be a real concern.

If the DOD spent half as much effort on reforming how they deal with sexual assault as they do on rewriting movies and TV shows, then they might have made more headway with one of the biggest problems the military has within its own ranks.