When the world’s pre-eminent energy watchdog says that the age of fossil fuels is over, it’s time to pay attention.

Some 98 of countries in the world are oil producers: they are fundamentally unprepared for what the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s flagship World Energy Outlook describes as the “unstoppable” decline of oil.

The IEA is an intergovernmental organisation based in Paris, representing 31 member-states and another 13 associate countries, who represent some 75% of global energy demand and include some of the world’s largest oil producers – including the United States, which is today the world’s largest.

The 2023 World Energy Outlook’s verdict is a wake-up call not just for the energy industry, but for the entire planet. The report concludes that based solely on existing policies and trends, global demand for oil, gas and coal will peak before the end of 2030 – that’s within the next 7 years – after which it will enter irreversible decline.

To be sure, the fossil fuel decline projected by the IEA is still an undulating plateau which lasts for about two decades before sloping downwards more dramatically. But even with this conservative forecast of decline, the idea that we’re on the cusp of the ‘beginning of the end’ of the oil age is unavoidable.

In 2030, the IEA finds, renewables will represent some 50% of today’s global power mix (up from 30%), resulting in reduced demand for fossil fuels across the board – dropping from the current 80% share of global energy consumption to 73% by 2030, and continuing to experience an accelerating decline from there.

This is not only the first time an IEA World Energy Outlook, widely-recognised as the most authoritative global source of energy analysis, has ever acknowledged that we’re facing the inevitable decline of fossil fuels; it’s also the first time the IAE has called for “measures to ensure an orderly decline in the use of fossil fuels”.

Which means that the IEA has finally caught up with what I and others have been saying the data points to for some time: that we’ve reached an irreversible inflection point in the global energy system, which is now in the throes of transformation.

The IEA is probably wrong, though

When the world’s global energy watchdog tells you that it’s time to start preparing for “an orderly decline in the use of fossil fuels”, you can bet on one thing: it’s probably way past time.

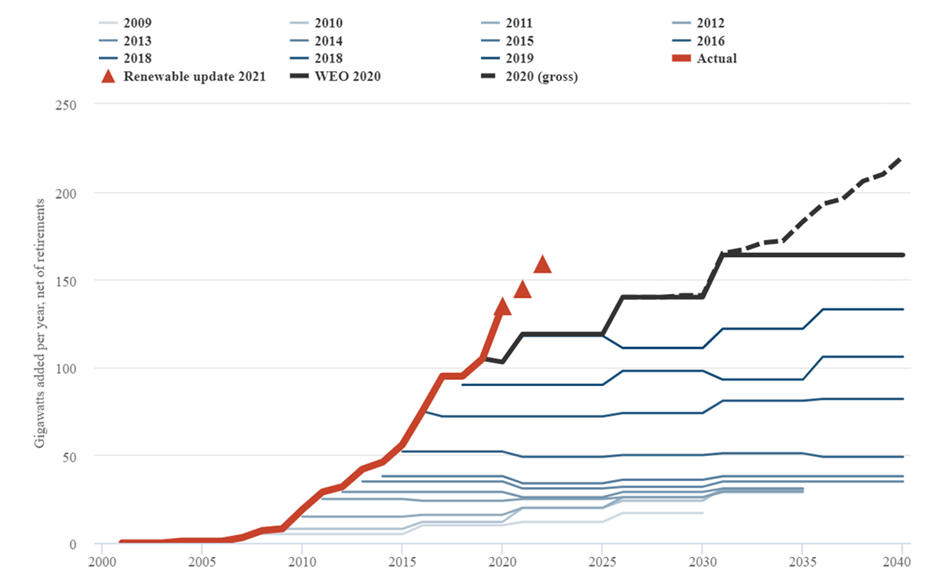

How do we know this? First of all, the IEA has been wrong for 20 years – and by wrong I specifically mean, wrong in forecasting the speed and scale at which renewable energy will grow.

As the graph above shows (check the blue lines on the right-hand side), the IEA has consistently underestimated how fast renewable energy will expand, projecting slow, linear progression. Yet year-on-year since 2000, growth has scaled exponentially.

This means that the IEA is probably absolutely right that we’re on the cusp of the beginning of the end of oil, but potentially catastrophically wrong on its assumption that after peaking around 2030, oil will gradually and slowly decline, firstly over a 20 year plateau, and then a bit faster after that.

This gives us the illusion that we have a comfortable window of another 30 odd years of stable fossil fuels.

The second thing which suggests the IEA is wrong is actual empirically-grounded technology forecasts which have a far better fit to real-world data than the IEA’s models.

Readers of AoT will be aware that the IEA’s welcome wake-up is backed up by technology forecasters from the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute. I analysed their landmark working paper some months back. That paper has recently been published in peer-reviewed form in the prestigious journal Nature Communications, sparking global headlines (but, naturally, you saw it here first).

Its core finding is that solar power is on track to “dominate” the global energy system by 2050 regardless of whether new climate policies are put in place, and based purely on currently unfolding economic dynamics of declining costs and improving performance.

In other words, over the next three decades we will experience an accelerating global energy phase shift which will increasingly disrupt the fossil fuel industries.

But the University of Exeter study is probably also conservative because it focuses exclusively on solar.

The energy system can’t be understood accurately through such a silo-ed lens. While it’s a brilliant and technically robust paper, due to the lens it adopts it doesn’t take into account how the scaling of solar and wind and batteries together will create self-reinforcing feedback loops that drive far faster exponential change within the energy sector.

And it doesn’t take into account unfolding technology disruptions taking off right now in two other foundational sectors – the transport and food systems, where electric vehicles, Transport-as-a-Service, precision fermentation and cellular agriculture, are all scaling exponentially in the same way.

As these technologies evolve and improve in costs and capabilities, this too will drive self-reinforcing feedback loops across the transport and food sectors which will further drive down fossil fuel demand.

Incumbent industries in the energy, transport and food sectors account for 90% of global carbon emissions, and thus the bulk of fossil fuel consumption today. This means it’s quite likely that these conventional studies fail to capture the full scope of the transformation ahead.

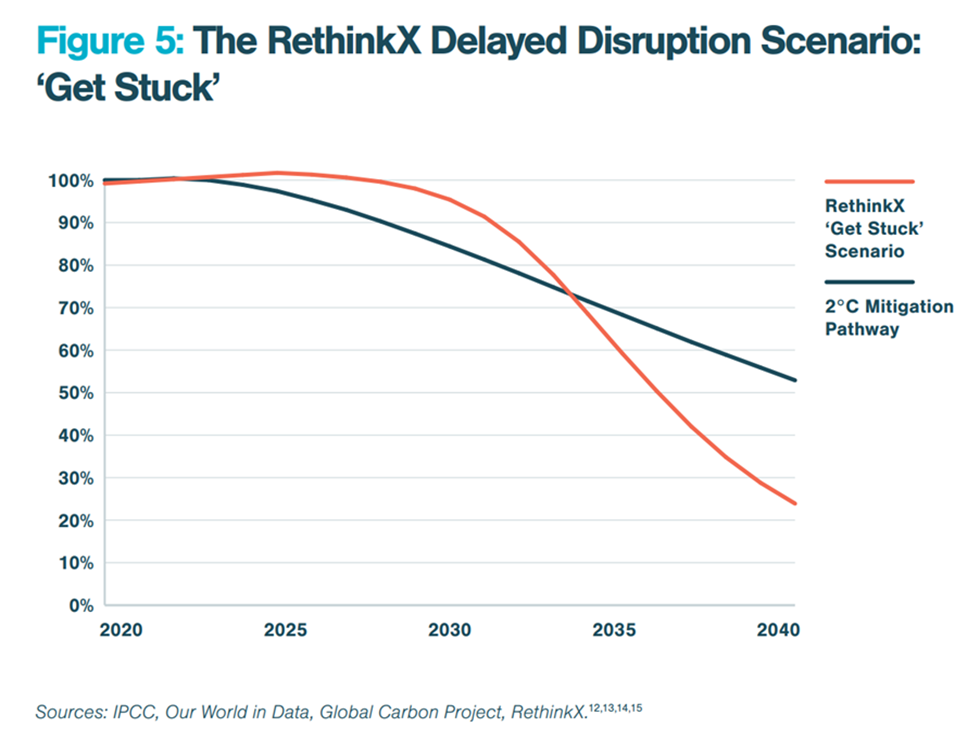

In Rethinking Climate Change, a RethinkX study for which I was lead editor (key authors are Adam Dorr, Tony Seba and James Arbib), we found that even in a worst-case scenario where we delay the disruptions, fossil fuel demand will decline rapidly from the late 2020s through to 2040. It’s still not fast enough to get us out of the climate danger zone (this scenario sees us breaching the 2C mark for nearly a decade – which could be sufficient to trigger irreversible tipping points) but it’s way faster than the incumbent energy industry and national fossil fuel producers are prepared for.

And then there’s another factor that the IEA’s World Energy Outlook fails to take into account: the speed at which US oil and gas production is likely to peak and decline well within the next decade.

A faster decline – US shale

At first glance, it might seem that the evidence of an imminent decline in US oil is scant if not contradictory. But look a little deeper, and a consistent thread emerges.

At one end of the thread is the story of ExxonMobil’s purchase of oil and gas assets in the Permian shale basin. This created huge excitement in the sector, and seemed to suggest that the Permian will be salvaged under the wing of the largest oil giant in the world.

But while efforts to consolidate in the US shale industry will continue with lucrative M&A deals, and while efficiency gains and technological trickery will work to prolong the decline as long as possible to squeeze out as much oil and gas as possible, the data is pretty clear. A report by Enverus Intelligence Research put its verdict out a few months ago. Dane Gregoris, report author, told the Journal of Petroleum Technology:

“The US shale industry has been massively successful, roughly doubling the production out of the average oil well over the last decade, but that trend has slowed in recent years. We’ve observed that decline curves, meaning the rate at which production falls over time, are getting steeper as well density increases. Summed up, the industry’s treadmill is speeding up and this will make production growth more difficult than it was in the past.”

While the report expects that US oil production will continue to grow, that growth will be limited by accelerating declines. The only thing that might incentivise increased capital spending on production growth and intensified drilling is higher oil prices – but the thing is, higher oil prices will not only strangle the global economy, they will make oil even more uncompetitive with emerging exponentially-improving clean energy technologies, which will be even cheaper by comparison.

In short, these factors will create an economic feedback loop that accelerates the decline of shale and the growth of renewables.

This also means that given the instrumental role of US shale in accounting for the vast bulk of global production increases, the twilight of shale signals that the IEA’s hoped-for decadal plateau is unlikely to last very long. We’re more likely to see global production peak and decline faster than expected as US shale reaches the limits that more and more industry insiders are recognising.

An existential threat

Incumbent industries are fundamentally unprepared for what’s coming. The IEA is beginning to catch-up with forecasts that I and others have been making for years. And they’re still way off the mark.

There are a range of serious risks on the horizon as a result.

Economic fallout

Oil and gas assets will be stranded – as they will not actually be able to generate the returns promised to investors, their projected valuations which form the basis of those investments are flawed. This means that trillions of dollars worth of assets will unravel. High oil prices will mask this coming crisis because they will convince investors and industry insiders that they are making gallons of profits, so why worry?

The problem is that demand will inevitably drop faster than expected as the energy, transport and food disruptions scale exponentially. At that point, it will become clear that those prices aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on.

Millions of people who work in the fossil fuel industries will face the fact that their jobs are at risk. The economic impact on these industries, those employed by them, and countries as well as industries dependent on them, will reverberate widely and extend well beyond the energy sector. The resulting economic crisis could reduce the capital needed, and the appetite, to accelerate the energy transformation.

Political fallout

Massive economic losses, declining industries, and millions more unemployed is, of course, a recipe for political disaster. Factor in intensifying climate impacts, one of whose consequences will be large-scale migration, and you have a recipe for extreme political polarisation.

A convergence of such disasters would likely drive the radicalisation of political thinking on both left and right. This will boost authoritarian politics, and fuel disillusionment with liberal democracy as a model of governance.

It will also undermine confidence in international institutions.

Geopolitical fallout

Few have attempted to consider the tremendous geopolitical implications of 98 oil producing countries finding that their core product is no longer in sufficient demand to economically justify staying in business.

The loss of oil revenues will destabilise many governments which are dependent on them to support public spending. This could see GDP collapse. Combined with political fallout, we could see escalating civil unrest on a far larger scale than ever before.

This could be particularly acute in the largest oil producing countries, who could find that without the funds to sustain their previous expenditures, the collapse of state institutions paves the way for the rise of extremist groups – a phenomenon we saw in Syria, for instance.

Socio-cultural fallout

The crumbling of prevailing fossil fuel industries may also amplify current trends we’re seeing in the form of a ‘greenlash’ – a public backlash against ‘green’ policies which blamed for societal problems. Already, a ‘greenlash’ has driven a wave of public fatigue on climate action due to perceptions that nothing is being done to alleviate the intensifying cost of living crisis, and fears that ‘green’ investments will only worsen things.

This could be compounded by sub-optimal and half-baked deployment of clean energy programmes resulting in a worst-of-all-worlds scenario in which the incumbent energy industry is being economically disrupted by new more competitive clean energy systems, which however are being rolled out in a haphazard way that fails to result in a system that is as cheap and robust as it could be.

That could fuel greater disillusionment with the energy transition and climate action, which would further undermine the transformation – and potentially abort it before its even complete.

The worst-case culmination of these risks is that they converge in such a way that we end up overshooting past a global climate tipping point while the global energy system essentially disrupts itself into a process of protracted collapse.

Those are the risks, but each of these risks also opens up unprecedented opportunities.

Or a new economy?

Economic transformation

Societies can build resilience to the economic consequences of oil, gas and coal disruption by divesting now, and reinvesting in the new technologies across energy, transport and food in particular.

The focus of this should be winding down investments, subsidies and major fossil fuels companies themselves on a science-based timeline to ensure, as the IEA suggests, an “orderly” transition away from oil, gas and coal, rather than a chaotic spiralling of economic crisis and collapse.

Part of this should involve incentivising and supporting incumbent energy companies to invest in and move into clean energy markets at scale. Ultimately, companies which successfully engage in this pivot will survive – only a few will be capable of doing so. All others will eventually disappear.

That will also require fast-tracking legislation to better regulate new emerging industries so that distributed ownership and entrepreneurship becomes more viable. This will accelerate the distributed deployment of these new technologies, which will rapidly become assets owned by individuals, households, businesses and communities. A different type of vibrant economic model will arise as a consequence.

Political transformation

Once the inevitable obsolescence of fossil fuel industries becomes clearer, the demand for government support to transition workers into the emerging energy, transport and food industries of the future will grow rapidly.

Widespread discontent with the prospect and reality of unemployment can be redirected via the recognition that this predicament was created by the incumbency, and therefore has to be transcended by empowering people to be integrated into the new industries where prosperity and innovation can be sustained.

The more governments, businesses and companies realise this, the earlier they can start preparing. Workers across industries can lay the groundwork for a movement premised on spearheading the transformation of our societies. Politics will be infused with a new type of energy enthused by the imminent prospect of abundance for all within planetary boundaries.

Geopolitical transformation

Societies which are dependent on oil exports should invest right now at scale in fast-tracking clean energy infrastructure. Their immediate focus should be on accounting for domestic demand.

They should also seek to diversify their economies by investing more broadly in emerging transport, food, information and materials disruptions which are already scaling or poised to scale exponentially over the next years and decades, as these will provide the most lucrative sources of new revenue.

It’s the same course of action for societies which are heavily dependent on oil imports. The only solution is to invest in a crash programme to wean off this dependence by becoming self-reliance on domestic clean energy.

The recognition that fossil fuels are no longer the 'big fish' will greatly ameliorate conflicts linked to these resources. This won't eliminate the risk of conflicts breaking out over other issues, but considering the central role of fossil fuel energy sources in radicalising conflicts since the Second World War, this will be a major inflection point in the international system.

Socio-cultural transformation

By pursuing all of the above at pace, and by clearly declaring the intention to commit to a fundamental transformation which will not be easy, but will bear the greatest fruits will mitigating the greatest harms, societies will be able to position themselves to take advantage of the global phase shift while distributing and maximising the benefits as widely as possible.

Simultaneously, they will be able to avoid the harms that will no doubt befall those that fail to embark on such actions. These action then will speak for themselves, going some way to demonstrate that accelerating rather than obstructing the transformation is the most rational path forward.

A new cultural paradigm could emerge that is focused on harnessing the new model of abundance within planetary boundaries. Societies will begin to see that participatory networks, cooperation and sharing are the keys to unlock value, rather than nihilist materialist competition in a zero-sum game for its own sake - instead healthy competitive dynamics will be focused on maximising mutual gains.

So there you have it - by no means are the scenarios and choices described above exhaustive. They only touch on the possibilities at stake. I hope they help you to reflect constructively on the times ahead, and how we can position ourselves to be as useful as we can in bringing forward a genuinely possible Age of Abundance.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In