The world in 2025 is witnessing convulsions across governance and geopolitics – from trade wars to tech titans. These upheavals, exemplified by Donald Trump’s recent tariffs and Elon Musk’s role at the “Department of Government Efficiency,” signal a deeper civilisational shift. Through the lens of planetary phase shift theory, we can see these developments as symptoms of a turbulent ‘release’ stage in a global adaptive cycle – a period of systemic breakdown, incumbent resistance, and the chaotic clearing of ground for something new.

The Planetary ‘Release’ Stage: A Civilisational Inflection Point

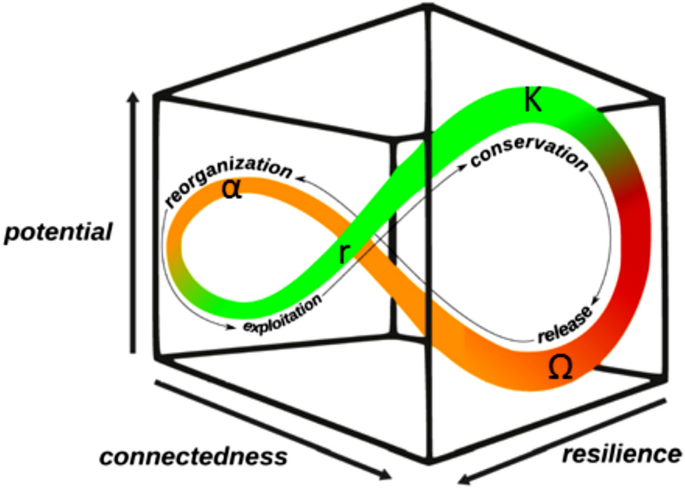

Planetary phase shift theory suggests humanity is entering the back-loop of a planetary-scale adaptive cycle – a concept from ecology and complexity science that describes how systems grow, accumulate, collapse, and reorganise.

In this framework, our industrial civilisation has passed a long growth phase and is now plunging into a “release” stage (sometimes called the omega phase or back-loop) characterised by disruption and collapse of entrenched structures. This stage is chaotic but also creative: as old connections sever and accumulated resources and information are released, they can recombine in novel ways. Crawford Holling, who pioneered adaptive cycle theory, described how the release of bound-up knowledge and capital creates an opening for “creative destruction” – unleashing “novel and unexpected” recombinations that can trigger regrowth or reorganisation into a new system. In short, the end of an old order carries the seeds of a new one.

The current polycrisis – a convergence of crises in climate, energy, economics, politics and culture – is symptomatic of industrial civilisation entering its release phase. Institutions and norms that long governed the post-WWII world are destabilising. There is a pervasive sensation of acceleration and uncertainty as familiar systems begin to fail. This turbulence, however frightening, is the result of an inflection point in humanity’s development.

When a complex system enters a phase transition, all its sub-systems go into flux. At the planetary level, we see this in everything from ecological upheaval (breaching of planetary boundaries) to technological disruption and social fragmentation. The release stage is thus an epochal moment of breakdown, in which entrenched structures unravel, making way (potentially) for new forms to emerge.

Crucially, as humanity moves deeper into the release stage, incumbent systems rooted in the industrial age will increasingly lose their effectiveness and meaning. The centralised, hierarchical institutions of the 20th century – from mainstream political parties to international bodies – are struggling to adapt. In this view, many of today’s extreme events and policies can be understood as manifestations of a system under stress, shedding its old skin. The incumbents of the dying order often resist fiercely, even as their paradigm evaporates.

This dynamic is evident in the United States where a newly re-empowered Trump administration is aggressively tearing up the fabric of the government and financial system. Trump’s sweeping tariffs, the dismantling of federal agencies, and US withdrawals from global institutions are not isolated policy choices – they are expressions of systemic turbulence in the release phase, attempts by the incumbency at the heart of the system to fortify its power in misguided ways by reorganising it along the lines of outmoded authoritarian political models of the early twentieth century (if not earlier).

Cracks in the Global Order: Tariffs and Trade Wars on a Planetary Scale

One of the clearest signs that the post-WWII global order is fracturing has been President Trump’s crusade against the very international free market regime spearheaded by the US for decades. In early 2025, Trump unveiled sweeping tariffs on practically every trading partner, a move that shocked allies and rivals alike and effectively declared an end to the decades-long era of trade liberalisation.

The administration imposed a 10% “baseline” tariff on all imports – a universal tax not seen in living memory – with even steeper duties for countries deemed unfriendly. US officials openly acknowledged these tariffs are the highest trade barriers the nation has erected in over a century. The result was an immediate jolt to the global economy: markets plunged and leaders worldwide reacted with alarm. Trump suddenly backtracked and declared a 90-day pause (except on China - which, as of the time of writing, now faces up to 245% tariffs on imports to the US). Having urged his followers to invest in the stock markets, they skyrocketed – prompting concerns of insider trading.

The upshot is clear. For Trump, the idea of a rules-based international system once avidly promoted by the US is out the window. The mask is off: the global financial system is ultimately a plaything of US power, especially for the profits of US corporate insiders close to the Trump regime.

For the international system built after World War II – one premised on reducing tariffs and increasing interdependence – Trump’s “America First” trade offensive represents a severe rupture. Long-time allies like Canada and the European Union, who benefitted from the US-led trade system, suddenly found themselves targets of punitive duties.

In true release-stage fashion, Trump has sought to break with the old constraints in pursuit of a new configuration – in this case, a radically protectionist US-centric economy. Trump has argued that across-the-board tariffs give Washington “great power to negotiate” better deals, even as his own officials send mixed messages about whether the tariffs are permanent or just leverage. Either way, the old multilateral trade framework (embodied by the WTO) is being cast aside. Indeed, Washington has doubled down by effectively hobbling the World Trade Organisation: the US stopped funding the WTO for 2024–25 and reiterated past threats to withdraw entirely, as part of a broader retreat from institutions deemed contrary to “America First” economics.

This follows Trump’s earlier blockage of WTO appellate judges, which already crippled its dispute mechanism. Now the message is unmistakable: the post-war trade order is effectively over, and something new – perhaps a fragmented system of bilateral deals and tariff walls – is taking its place.

From the perspective of planetary phase shift theory, this trade upheaval can be seen as part of the “release” of long-stable structures. For roughly 75 years, global trade rules and institutions acted as load-bearing pillars of the international system (part of the “front-loop” of growth since WWII). That system enabled tremendous growth and integration, but also accumulated rigidities and inequalities. Now, under stress from populism and geopolitical rivalry, those pillars are cracking.

Trump’s whipsawing tariffs are smashing the brittle facade of neoliberal globalisation, releasing pent-up pressures. In complexity terms, this is a phase transition in the global economic sub-system – a rapid shift from one equilibrium (open trade) toward a new, uncertain state. The chaos of tit-for-tat tariffs and shattered alliances is the entropy that accompanies the release phase. We are witnessing a dramatic increase in system volatility: supply chains re-routing overnight, corporations like automakers laying off workers or moving production in response to tariff shocks, and nations exploring new trading blocs out of necessity.

The space of possibilities for the global economy has suddenly expanded, for better or worse. Scenarios that were unthinkable a few years ago – a permanent US-China economic decoupling, a split global trading system, even the US trading mostly inside a protectionist bubble – are now on the table.

This is the combinatorial explosion of the release phase: once the old rules fall away, myriad new configurations (trade alliances, local industries, black markets, technological workarounds, etc.) rush to fill the void. Whether this yields a more resilient reorganisation or a deeper collapse (a global depression) remains to be seen. But clearly, Trump’s erratic trade war strategy is accelerating the dissolution of the old economic order, a hallmark of our era’s systemic turbulence.

America Unbound: Withdrawing from the Institutional Architecture of the 20th Century

Trade is only one front in Trump’s assault on the post-WWII global architecture. Since returning to office, he has moved swiftly to pull the United States out of key international agreements and institutions – actions that symbolically slam the door on the era of US-led global multilateralism. On Day One of his second term, Trump fulfilled his campaign pledge to withdraw from the World Health Organisation, signing an executive order to terminate US membership in the UN’s global health body.

This came at a time when global coordination on public health (still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic) is crucial. Trump justified the withdrawal by reviving his accusation that the WHO is “owned and controlled by China” and had “ripped us off” during COVID.

With the stroke of a pen, the US – historically the WHO’s top funder and a key player in global disease response – turned its back on that cooperative framework. Public health experts warn of dire consequences, from disrupted vaccination programmes to reduced pandemic preparedness, as the incumbent hegemon retreats into extreme nationalist scepticism.

Within the same first week, the administration also took aim at international climate cooperation. Trump re-withdrew the US from the Paris Climate Agreement (which the prior administration had rejoined). Calling the accord a “one-sided… rip-off” that would “sabotage our own industries while China pollutes with impunity,” Trump declared that America would not honour the emissions-cutting pledges made in Paris. Along with Paris, a raft of other Biden-era climate initiatives were scrapped. In effect, the US federal stance on climate reverted to the industrial-age mindset of prioritising fossil-fuel industries (underscored by Trump’s concurrent declaration of a “national energy emergency” to boost oil and gas production).

International security alliances have also been shaken. Trump’s antipathy toward NATO, the cornerstone of Western security since 1949, resurfaced in force. While he has stopped short of a formal NATO exit, analysts warn that NATO may not survive a second Trump term intact. The President has made it clear he expects allies to radically increase defence spending and acquiesce to a “reorientation” of the alliance more to Washington’s liking.

Trump’s talk of “cutting a deal” with Vladimir Putin over Ukraine – potentially freezing or resolving the conflict on terms favourable to Moscow – underscores this anti-West shift threatening to upend the post-Cold War consensus.

Europeans are understandably anxious: uncertainty hangs over US security guarantees, and the transatlantic bond is fraying under the strain of Trump’s transactional approach. Even if NATO’s treaty remains formally in place, US behaviour – like suspending military exercises, or refusing to defend an ally deemed a “free-rider” – could effectively hollow out the alliance. In Asia too, US alliances with Japan and South Korea face new uncertainty as Trump insists partners pay more or face troop drawdowns.

Layer by layer, the scaffolding of the liberal international order is being removed. Beyond WHO and Paris, the administration has hinted at pulling back from other UN agencies and agreements on everything from human rights to arms control. Funding has already been slashed or frozen for several UN programmes.

In systemic terms, the United States – which long functioned as a linchpin of the global “organising system” at the global scale – is now behaving like a rogue sub-system. This retreat can be seen as the incumbent superpower shedding the commitments of the old order in an attempt to rediscover freedom of action. It is a high-stakes gambit. On one hand, withdrawing from international entanglements satisfies a nostalgic vision of national sovereignty and may temporarily shore up a sense of control. On the other hand, these moves also dissipate the soft power and leadership capital the US accrued over decades. US global leadership, once taken for granted, is now rapidly losing meaning as America becomes a spoiler of the very global order it once presided over. The “information gap” between the old narrative (America as world leader) and the new reality (America as self-interested actor) is widening, causing confusion and strategic recalculations worldwide.

The turmoil of this moment cannot be understated. In previous eras, US withdrawal or isolationism has heralded instability – we need only recall the 1930s for an example, when American disengagement contributed to a breakdown in international order. Now, as part of a larger planetary phase shift, the stakes are even higher: global problems like pandemics and climate change do not pause for nationalist interludes. Other powers and institutions are scrambling to adapt. The European Union has begun to formulate plans for greater strategic autonomy, attempting to uphold multilateral initiatives without US support. China is eagerly stepping into the void, positioning itself as a defender of globalisation (albeit on its own authoritarian terms). In effect, the collapse of the old US-led order is unleashing a flurry of new geopolitical combinations – from BRICS expansion to regional pacts – as the world gropes toward a new equilibrium. This proliferation of initiatives is analogous to the “release” of many potential seedlings after a forest fire. Not all will survive; some may prove maladaptive.

Dismantling the State: The “Government Efficiency” Coup

Perhaps nowhere is the incumbent resistance to systemic transformation more visible than within the US federal government itself. Trump’s 2025 agenda doesn’t stop at unravelling world order – it also targets the American government itself.

Even before Elon Musk’s escalating involvement, Trump signaled his intent to reassert presidential control over the civil service in unprecedented ways. As soon as he took office in January 2025, he prepared an executive order to revive and expand “Schedule F,” a job classification that would strip employment protections from tens of thousands of federal workers in policy-related roles. This move aimed to ensure that all levers of executive power answer directly to him. Never in modern US history has a president attempted such a sweep of the bureaucracy. Critics have described it as a plan to install a “secret police” of political loyalists throughout government, warning that it will eviscerate the merit-based, nonpartisan civil service and concentrate power dangerously in the White House.

Meanwhile, Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has provided the ideological and analytical backing for the broader effort to remake government. The very acronym “DOGE” – which evokes the Shiba Inu Dogecoin meme that Musk famously propelled – suggests that governance itself is being memefied and disrupted in the spirit of Silicon Valley bravado.

In the frame of the adaptive cycle, this is an attempt to force a controlled burn of the dense underbrush of government. The federal bureaucracy, in this metaphor, is an old forest that has grown over decades (sometimes becoming overly complex, slow, or unresponsive, as critics claim). The DOGE initiative is like setting fire to that forest to clear space. It is release-by-design: a deliberate acceleration of collapse in the belief that something stronger and more efficient will rise. Yet lacking meaningful design principles. It doesn’t take an ecologist to understand that fire can be unpredictable and dangerous. Slashing 75% of the workforce in a short span means losing vast amounts of institutional knowledge and capacity. Government services that millions rely on could fail or face severe delays. Even functions vital to the economy – like food safety inspections, air traffic control, or Medicare payments – could be thrown into disarray if handled incautiously. The risk of chaos is extreme. In complexity terms, removing too many constraints and feedback mechanisms from a system can lead to its collapse rather than its renewal. Which, arguably, may well be the point.

From another angle, Trump and Musk’s government collapse spree can be seen as the incumbent elite’s attempt to perpetuate their power during the release phase by pre-emptively breaking the tools that might check them. Many of the ‘excess regulations’ and ‘bureaucratic’ functions targeted are those that enforce accountability – environmental rules, financial oversight (like CFPB), anti-corruption safeguards, etc. By dismantling these, the administration frees itself (and its industry allies) to operate with fewer restrictions. It is no coincidence that Musk’s companies stand to benefit from a government with weaker labour regulations, looser environmental reviews, and greater public-private “partnership” opportunities. The DOGE caucus in Congress already has enthusiastic members who see gold in privatising or digitising government services.

This is heralding a new fusion of corporate power with state functions – a reorganisation that, while touted as “efficient,” in reality aims to entrench the influence of a few billionaire technocrats over public policy. In effect, incumbents are using the chaos of the release phase to solidify their own positions, steering the destruction in ways favourable to them. It’s a classic pattern in history: during periods of upheaval, certain actors grab the opportunity to reshape structures to their advantage.

Incumbent Resistance and the Dynamics of Collapse

What unites Trump’s global belligerence and domestic “slash-and-burn” governance is a common thread of incumbent resistance amid systemic turbulence. In a period of breakdown, we often see powerful factions doubling down on familiar paradigms – even amplifying the very causes of the crisis – in an attempt to stave off change or reclaim a lost golden age. Trumpism is in many ways a reactionary response to the complex challenges of the 21st century. Faced with economic insecurity, geopolitical shifts, and cultural transformations, it retreats to nationalism, protectionism, and authoritarianism. This is a form of ‘release resistance’: rather than facilitating a smooth transformation to a new equilibrium, the incumbent force (here, the tech oligarchy, fossil-fuel-powered, nation-centric industrial order) thrashes against the encroaching future.

Consider climate change – arguably the paramount systemic crisis driving the planetary phase shift. The rational, adaptive response in a reorganisation sense would be to transform our energy, transport, and industrial systems rapidly. Yet the Trump administration’s response has been to exit climate agreements, declare an energy emergency to boost oil production, and remove environmental regulations. It is doubling down on the high-carbon status quo, even as that status quo visibly destabilises the planet (worsening wildfires, floods, etc). This incumbent behaviour fits a pattern: in complex systems, when feedback signals (like climate impacts) indicate that a regime is unsustainable, actors invested in that regime often intensify their exploitation in the short term, either out of denial or the desire to extract the last remaining benefits. It’s a dangerous gambit that can hasten collapse.

Trump’s policies exemplify that very temptation – a clinging to coal and oil, to 20th-century manufacturing supremacy, to the “good old days” of American dominion. The “Make America Great Again” slogan itself is a paean to an imagined past. In systems language, it’s a refusal to accept that the old equilibrium (mid-20th-century industrial boom times) is gone. Instead of innovating forward, incumbent resistance tries to roll back the clock, or at least fortify the present against the inexorable tides of change.

Another aspect of incumbent resistance is the manipulation of information to maintain control. In the release stage, the credibility of old narratives and institutions often erodes (we see growing distrust in government, in media, in science). Into that void, new narratives flood in. Many are fragmentary, misleading, or extreme – a hall of mirrors of escalating cultural and political polarisation.

Trump’s political success has been deeply tied to his mastery of polarising narratives (e.g. the 'deep state' conspiracy, election fraud claims, xenophobic tropes). These narratives serve to rationalise and legitimise the dismantling of institutions. For instance, by persuading a significant portion of Americans that the federal bureaucracy is a hive of “Marxists” or “weaponised” against conservatives, that the US is plagued by "criminal" immigrants, it becomes easier to justify purges and extreme reforms. Similarly, painting allies and international bodies as exploiters of the US provides cover to withdraw from them. In essence, incumbent resistance weaponises disinformation as a tool to accelerate the release of old structures while deflecting blame for the ensuing chaos.

Complexity science tells us that as systems become more stressed, their behaviour can become erratic and oscillatory. We see this erratic oscillation in US policy: within a span of a few years, America swung from leading global cooperation (under one administration) to torpedoing it (under the next). Such wild swings themselves are symptomatic of a system in flux, lacking a stable attractor. They also confuse other actors – allies, markets, citizens – reducing the overall ability of the global system to 'sense-make' and respond coherently.

In a very real sense, the information environment is in chaos, amplifying the physical and institutional chaos. Social media networks (one of which is owned by Musk) amplify extreme viewpoints and false information, contributing to polarisation. This is the informational dimension of the planetary phase shift: humanity’s shared sense-making structures (media, education, science communication) are fragmenting, which makes collective action on global challenges even harder. As a result, incumbent factions find fertile ground to push simple, emotive narratives over complex, nuanced truths. The success of a simplistic solution like “build a wall” in the face of the enormously complex drivers of migration exemplifies this dynamic.

Of course, in a release phase, resistance can also come from those trying to mitigate the damage of collapse or preserve critical functions through the transition. However, what we label “incumbent resistance” here refers to forces aligned with the old paradigm’s power structure (fossil fuels, authoritarian nationalism, corporate oligarchy) that resist the emergence of any new paradigm that might threaten their status and power. That often means blocking or rolling back progressive or cooperative initiatives – exactly what we observe with Trump’s wholesale reversal of policies on climate, global health, and social equity programs.

In this turbulent dance, Elon Musk represents a dangerous hybrid figure. He is an incumbent in some respects (one of the world’s richest men, now wielding governmental influence) but also a disruptor in others (deploying private rockets shaking up the aerospace old guard). Musk’s involvement in DOGE could be interpreted in two ways. On one hand, it’s a sign that the traditional political class has lost its monopoly – a tech magnate is now shaping government reform, reflecting a novel recombination of social power encompassing private tech and state power.

On the other hand, Musk’s ethos of 'efficiency' and colonising new frontiers aligns with a Social Darwinist streak that is compatible with Trump’s agenda. His plan to optimise government means turning government into a corporation – one that favours his own business interests, and those of his allies. Musk’s presence thus adds another layer to the incumbent vs. transformation story: the rise of technocrats and oligarchs as power brokers in the vacuum left by the smashing of public institutions. This is a phenomenon seen in history when states weaken – powerful private actors step in (think feudal lords in the twilight of empires, or oligarchs in post-Soviet states).

Chaos as a Catalyst: Towards a New Adaptive Cycle

Is there a silver lining to all this upheaval? The planetary phase shift framework reminds us that release is not the end – it is a stage that precedes reorganisation (the alpha phase in adaptive cycle terms) The destruction also frees up resources and opens minds to possibilities that were previously unthinkable.

Already we can see nascent seeds of the next cycle sprouting in the cracks of the old. For example, the shock of US retrenchment is prompting US allies in Europe and Asia to collaborate in new ways with each other, reducing over-reliance on a single hegemon. There are discussions of new security architectures – perhaps a European defence initiative, or stronger Asian regional pacts – which might in the long run create a more multipolar but resilient order.

In trade, countries affected by the tariffs are innovating: some are pivoting to regional markets, investing in domestic production, or adopting digital trade mechanisms to reduce tariff exposure. These adaptive responses could form the kernel of a new, more diversified global economic system less centred on US consumption.

Within the US, even as the federal government is thrown into disarray, some states and cities are stepping up as ‘subnational’ actors on the world stage. During Trump’s first withdrawal from Paris, a coalition of states and businesses declared “We Are Still In,” continuing to pursue climate goals. We see similar patterns now: states like California and New York remain engaged with international climate initiatives and maintain their own environmental standards, effectively circumventing federal rollbacks. This hints at a future where governance is more distributed – local and regional authorities networking across borders to tackle mutual challenges.

In fact, the breakdown at the federal level might accelerate experiments in participatory economics and governance at smaller scales, as people lose trust in Washington and seek alternatives. The adaptive cycle’s lesson is that innovation often comes from the periphery during a release – think of small mammals thriving as dinosaurs perish. In our context, grassroots movements, community cooperatives, and agile start-ups might carry forward solutions (in renewable energy, circular economies, social equity) even as big government and big corporations struggle.

The transition to a new civilisational life-cycle is not guaranteed to succeed, but there are clear material and cultural disruptions already unfolding at pace that reveal the momentum of change within the system. The release phase can lead to collapse if regenerative forces are squashed or if destructive forces run unchecked. The challenge is to minimise the forces of collapse while laying the groundwork to allow the seeds of the next life cycle of civilisation to blossom. In practical terms, this means seeking ways to temper the worst excesses of the current turbulence (e.g. preventing trade wars from igniting real wars, or ensuring the social safety net isn’t completely torn apart by austerity measures) while actively fostering the transformative innovations (distributed deployment of clean energy, decentralised global cooperation networks, etc) that can form the core of a new system.

What comes after the release? If Trumpism represents the last gasp of a certain petro-nationalist industrial order, what worldview replaces it? The next system, to survive, has to embrace planetary consciousness and stewardship values – seeing humanity as part of an interconnected earth system, and reorganising our economics and politics accordingly.

The emancipatory potential of such a new system is immense. And this is precisely why incumbents seek to resist it, as it could not be further from the zero-sum ethos of “America First.”

And yet, the very failures of that ethos might propel public awareness toward the necessity of a new paradigm. As the old narratives prove incapable of solving our crises, a space for new narratives of mutual thriving and ecological balance will emerge. Information flows, once they overcome the polarisation, can spread empowering stories of what’s truly possible for society not in the far future, but today. Younger generations all over the world are already far more invested in issues of climate restoration, equality, and technological open-sharing – values that align with a post-industrial, post-carbon civilisation. In complexity terms, these values and ideas are 'strange attractors' that could shape the next stable regime.

The planetary phase shift framework reminds us that multiple future paths compete during reorganisation. The path that wins out will depend on what ideas and actors can take root in the fertile soil of the post-release clearing. It is up to civil society, leaders at all scales, and citizens to ensure that the path forward is one of regeneration and not a collapse into neo-feudalism, technofascist hypercapitalism or another variant of dystopian regression.

Trump’s policies and Musk’s governmental foray are dramatic upheavals that confirm the old stability is gone. We are living through the period of total flux that precedes a new system state. It is chaotic and terrifying – but understanding it in the context of a planetary adaptive cycle can be empowering. It tells us that there is a pattern to the madness, that through the accelerating release of materials and energy a space for renewal opens up. The incumbent powers are scrambling – some to preserve their dominance, others to adapt – but beneath that scramble new dynamics are emerging.

We are witnessing the evaporation of the industrial paradigm, with all its attendant crises. The seeds of the next life cycle of civilisation are already taking root in this very turmoil. If we can navigate the present turbulence – mitigating its worst harms and nurturing its creative potentials – we can scale the release stage by cultivating and calibrating the forces of reorganisation in alignment with a planetary equilibrium. The choices being made now, in the halls of power and on the streets alike, will determine whether this Age of Transformation is one of renewal or collapse. In this pivotal moment, understanding the forces at play is the first step towards guiding them. As the old world burns, the task before us is to ensure that what rises from the ashes serves the flourishing of life on Earth, not just the narrow interests of yesterday’s incumbents and their tech bro protectors.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In