In a new post titled ‘Techno-Optimism Won’t Save the Day’ Rachel Donald of Planet: Critical offers a critique of my piece at Age of Transformation debunking the myth that energy transitions don't happen. She writes that my article aims to “rebuke claims that technological disruption is not enough to force through anything resembling an energy transition”. Weirdly, although I appeared on Planet: Critical twice, throughout her piece she does not refer to me by name, but instead describes me as “a consultant”.

Donald makes a number of valuable points about the inertia of change, the persistence of fossil fuels, and the ultimate necessity of economic transformation. But her piece also makes several conspicuous data errors, and ignores other crucial data confirming the reality of energy transitions.

Important for me to point out where we agree. I agree that fossil fuel consumption continues to grow, that technology alone cannot save us, that a renewable energy transition must come part and parcel with efforts to reduce demand and that this requires economic transformation.

Fundamentally, we appear to disagree on whether an energy transition of any kind is in fact underway at all.

Rachel Donald’s core position seems to be that no energy transition can happen within capitalism. Therefore, we have to dismantle capitalism before an energy transition is possible.

My position is that 1. renewables can, have and will increasingly disrupt fossil fuels based on the same dynamics of technology disruptions in history which have been empirically-validated; 2. technological change alone cannot save us because it can only succeed with an accompanying socio-economic transformation (otherwise it will generate destructive rebound effects); 3. so we need both technological and organisational change, but each can have feedback effects into each other.

Below I address Donald’s key points on their own terms.

US emission decline does not correlate to US GDP

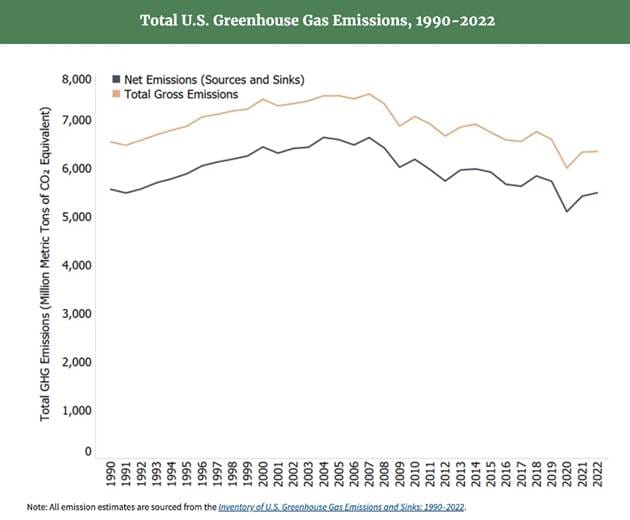

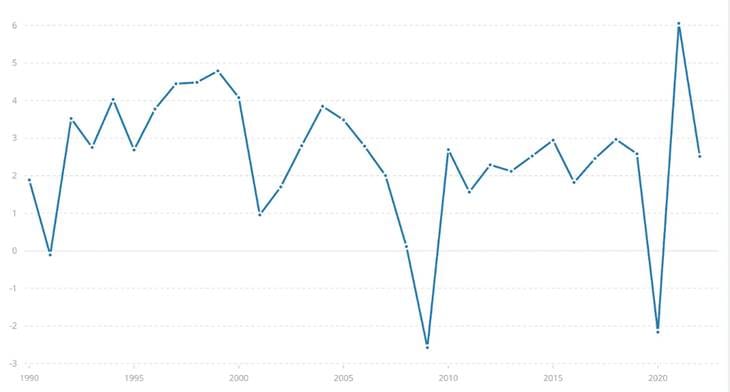

Donald argues that: “The USA’s emissions decline of 3% mirrors the economic declines triggered by the banking crisis in 2008 and the pandemic in 2020” and that “renewables have not led to that decrease”. She adds: “the emissions decline mirrors the overall decline in energy production those same years across all energy sources.”

It’s worth noting that my piece doesn’t really make an argument about emissions. I focus on showing that energy transitions leading to absolute declines in previous energy sources have and do happen, contrary to the thesis of the book More and More and More by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. So I have no problem in principle with the point she is trying to make here.

The problem is that her specific point simply goes too far. She bases it on displaying two graphs, one of US emissions and one of US GDP.

Donald is right that declines in energy consumption at these key points played a major role in declines in carbon emissions. I certainly at no point suggested economics does not play a role in emissions. However, the claim she derives from this - that renewables played no role in overall US emissions reductions - is incorrect.

Already have an account? Log In

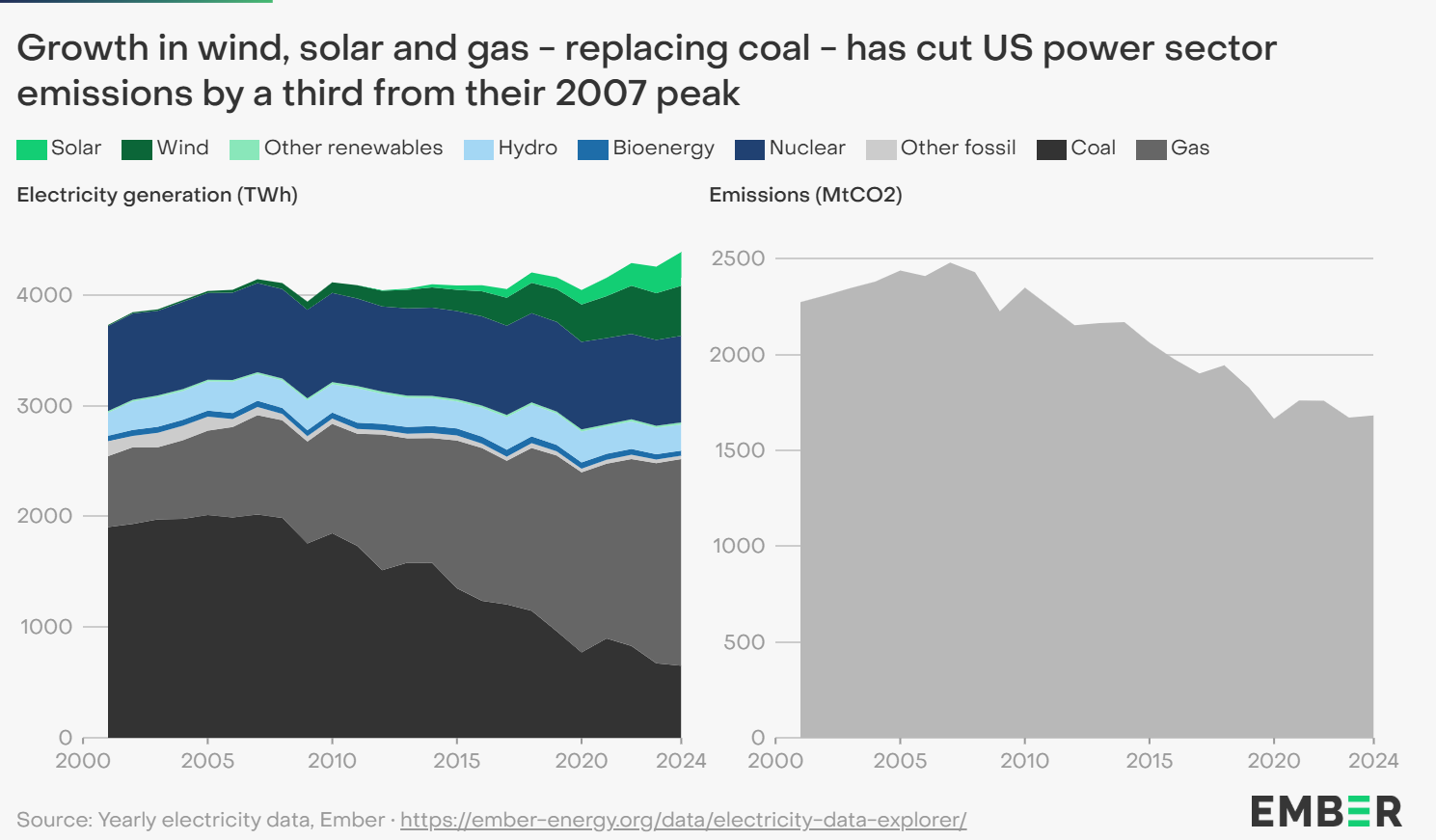

The very graphs she uses show the opposite of what she claims – the graph of US emissions demonstrates a consistent trend of decline from its peak in 2007 until today. The emissions decline not only doesn’t ‘mirror’ rising US GDP, it actually exhibits a trend of decline that is disproportionate to the trend of US GDP rising.

Now I’ve actually been quite critical of theories of absolute decoupling and am not trying to defend that approach. But Donald doesn’t actually look at any data here - she just says that these graphs “mirror” each other. Which they clearly don’t, unless we're being quite fast and loose by what we mean by 'mirroring'.

Look at the spike in GDP growth after 2020, climbing higher than the previous peak in the late 1990s. Despite that 2020 GDP spike reaching a level far higher than in 2005, US emissions levels are still decreasing and far lower in 2020 compared to 2005.

Let’s break this down further. US CO₂ emissions in 2021 were about 2.3% below 1990 levels. However, this modest net decline masks a peak and fall: emissions peaked around 2007 and by 2021 were 15% below that peak. Certainly, the large drops align with 2009 (global financial crisis) and 2020 (COVID lockdown) – e.g. 2020 saw a historic plunge to 4.58 billion metric tonnes (down 11% from 2019). But emissions did not fully rebound after these downturns despite increased GDP. Instead, from 2010 onward, US emissions remained flat or trended downward even as the economy recovered. For instance, by 2019 (pre-pandemic), emissions were 5.15 Gt, still 15% below 2007 despite a decade of economic growth. This indicates that structural changes in the energy system (not just recessions) helped curb emissions. Sectorally, the power sector led the decline: its CO₂ output dropped 36% from 2005–2022. Meanwhile, transportation (now the largest sector at 29% of emissions) was roughly flat pre-2020, and industry and buildings saw modest declines.

So while US energy consumption did dip in 2009 and 2020 due to lower economic demand, contributing to emissions drops, outside of those crises energy use not not only remained high but even grew, while emissions stayed below peak. Total primary energy use actually nearly recovered to mid-2000s levels by the late 2010s, yet CO₂ emissions stayed well below the 2005-2007 highs. This shows that emissions fell without a proportionate collapse in energy demand.

In short, Rachel Donald is incorrect to attribute the US emissions drop solely to economic downturns. It’s entirely valid to recognise that the drops in economic demand impacted emissions – but entirely wrong to suggest energy transitions in the power sector played no role in the overall emissions decline. A point that her next graph demonstrates quite nicely.

Emissions declined despite energy production increasing. How?

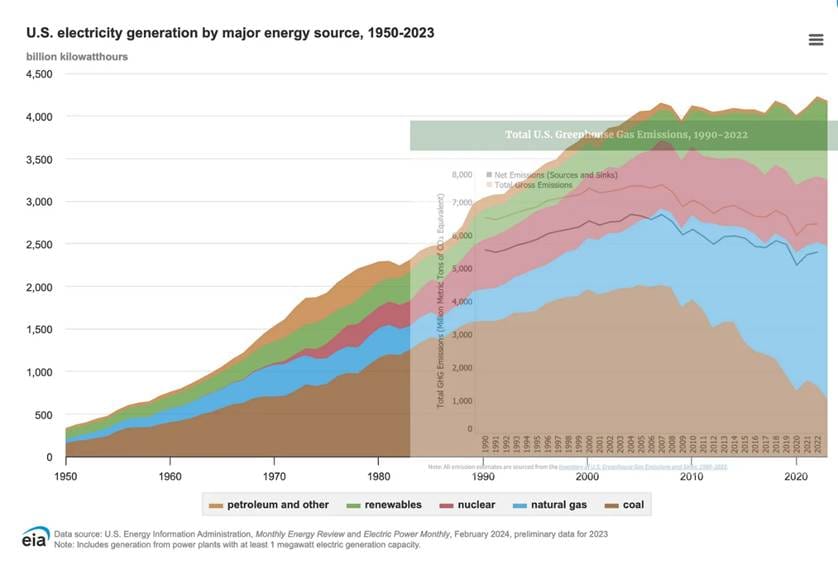

In the third graph, Donald superimposes the decline of US emissions against US electricity generation for the same period. She incorrectly says that: “... the emissions decline mirrors the overall decline in energy production those same years across all energy sources.”

What overall decline?

This is a misinterpretation of the graph, which illustrates precisely the impact of the energy transition. Contrary to Donald’s assertion, electricity generation is increasing in this period, but the composition of the US energy system is changing dramatically.

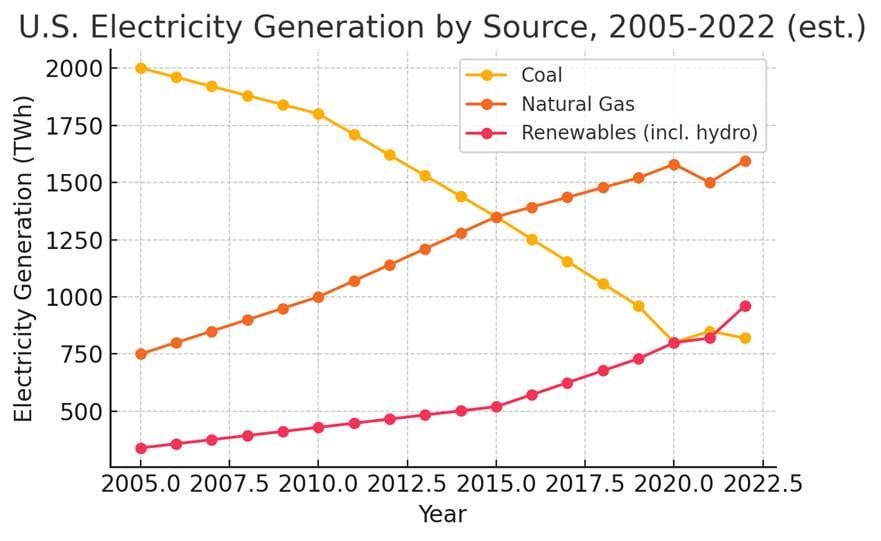

The graph depicts exactly my point about the US energy transition, showing electricity production from coal crashing down, with natural gas at first competing and disrupting and playing a large role in generating electricity, disrupting coal; then with renewables making up the rest and increasingly accelerating its own role in the disruption. This disruption of coal by gas and increasingly by renewables is what explains the decline in emissions in this period even as US electricity generation increases and while GDP goes up.

UK-based energy think-tank Ember has explained the transition in detail in its US Electricity 2025 Special Report:

In my previous piece, I explicitly mention the role of gas as part of the energy transition. My point is simply that Jean-Baptiste Fressoz’s thesis in More and More and More that new energy sources are nothing more than additive, driving an increase in all energy sources, is disproven by specific cases which reveal how the scaling up of new energy sources – in this case gas and then renewables – can increasingly disrupt and displace the incumbent (in this case, coal).

This is what we’d expect with a technology disruption. Coal is the least competitive and so is being outcompeted. Gas is next in line.

Yes, renewables and gas are displacing coal: and it’s increasingly renewables

“The energy source which is gobbling up the majority of coal’s former share, as you can see from the graph above, is methane gas, which the USA has become the largest producer of in the world over the past decade,” says Donald. This is supposed to be evidence that renewables are not ‘replacing fossil fuels’.

But in my own piece, I pointed this out: “The data shows exactly what replaced it: since 2007, US wind and solar generation increased by 722 TWh, and natural gas generation increased by 968 TWh, together compensating for the coal drop.”

Her observation about gas is of course true, and it validates the point I’m making – energy transitions do happen, and when they do, the predominant energy source can experience an absolute decline as the next energy sources disrupts and replaces it driven largely by economic factors. Here, Donald ignores the data in the same graph showing an accelerating role for renewables in disrupting coal.

Here I present data focusing on exactly how coal is being disrupted, by both gas and coal:

Many studies have examined this data and noted the importance of both energy sources in disrupting coal.

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, for instance:

US net emissions declined 15 percent from 2005 to 2021 due to a range of market- and policy-related factors. Electric power sector emissions fell 36 percent (through 2021) as a result of a shift from coal to natural gas, increased use of renewable energy, and a leveling of electricity demand.

This conclusion is backed up by numerous studies. For instance, one 2019 study focused on the collapse of coal in Climate Policy found that: “Declining US coal use is primarily caused by competition from natural gas and renewables not by environmental regulation of the coal sector.”

The World Resources Institute observes:

In the US and in virtually every region, when electricity supplied by wind or solar energy is available, it displaces energy produced by natural gas or coal-fired generators. The type of energy displaced by renewables depends on the hour of the day and the mix of generation on the grid at that time. Countless studies have found that because output from wind and solar replaces fossil generation, renewables also reduce CO2 emissions.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis concluded in 2021 about coal’s decline:

Undercut first by gas generation that benefited from falling prices from fracking, and now by a relentless buildout of lower-cost renewables (both resources posted record-high shares of the generation market in 2020), the share of power from the aging coal sector slumped to what may have been the lowest level since the dawn of the electric age in the US, 140 years ago.

In 2005, coal power plants produced on the order of 1,800–2,000 TWh, accounting for roughly 50% of US electricity generation. By 2023, coal generation had plummeted to 675 TWh, only about 16% of total generation. This represents a 65% absolute decline in coal’s output and a steep drop in its share of the generation mix. Coal-fired generation peaked around 2007 and then entered a steady decline. Coal basically went from the dominant source of US electricity in the mid-2000s to a minority contributor by 2023.

This ongoing collapse is a classic disruption, and is evidence of an energy transition.

This steep decline (coal output in 2023 is about one-third of its 2007 peak) marks a historic shift in the US power mix. We can see this by looking at data on structural shifts in the power sector’s assets. From 2005 to 2022, around 100 GW of coal capacity (about one-third of the fleet) was retired, dropping US coal plant capacity from 321 GW to 219 GW . The remaining coal units also ran far less often – average coal plant utilisation (capacity factor) fell from 67% in 2005 to 35% by 2022, as many plants went from baseload to seasonal or peaking duty. In contrast, over the same period gas-fired capacity grew (especially efficient combined-cycle plants) and their utilisation increased. Wind and solar capacity exploded – US wind capacity hit 141 GW and utility-scale solar 71 GW by 2022 (plus 61 GW₁ of small-scale solar).

As coal declined, natural gas and renewable energy (especially wind and solar) rose to fill the gap (yes, they replaced coal!). From 2005 to 2023, US coal generation fell by about 1,200 TWh. Over the same period, gas-fired generation increased by roughly 1,050 TWh, while renewable generation (wind, solar, hydro, biomass) increased by about 500–550 TWh (wind and solar alone up 570 TWh). This implies that natural gas accounted for roughly two-thirds of the replacement energy for lost coal output, with renewables accounting for roughly one-third over the full 2005–2023 span, a figure that is rapidly increasing.

Overall, the data show that natural gas was the primary direct replacement for coal in the 2005–2015 period; but from 2016-2025, renewable energy has taken on a growing role in replacing coal especially in the last 8 years. This trend is expected to continue as wind and solar capacity rapidly expand. Donald's blanket insistence that “renewables have not replaced coal” is therefore just not true – while gas shouldered most of the load initially, renewables by 2023 have significantly eaten into coal’s share and are now displacing coal generation at scale.

Looking at specific cases, such as Texas and California, further reveals how the argument of no energy transition is so misleading. California has virtually eliminated coal from its in-state generation. In 2023, coal accounted for only 0.1% of California’s electricity (only a small 57 MW industrial cogeneration plant remains on coal). California instead relies on a mix of natural gas (44% in 2023), renewables, and imports. Over 41% of California’s in-state generation in 2023 came from non-hydro renewables (primarily solar and wind), alongside 7% hydro and 7% nuclear – leaving little room or need for coal.

As noted above, the initial disruptor here was gas. But this was quickly followed by renewables, which is continuing to scale-up. The combination of California’s aggressive renewable portfolio standards, carbon policies, and the availability of gas and imported power led to the complete displacement of coal. So yes, energy transitions can be done. What we need to do is look at what works and do them better to rapidly phase out not just coal, but gas and oil.

Europe is phasing out coal, but it’s not? (well it is)

On Europe, Donald concedes that coal is indeed being phased out but doesn’t seem to acknowledge, again, that this is because it is literally being increasingly replaced by renewables at scale.

Instead she writes:

“The author correctly shows that coal is being phased out of Europe’s energy generation, and, in 2020, renewables produced more electricity in the EU than all fossil fuels combined. What he fails to mention is that the EU imports more than half of its energy (62% in 2022), and that renewables still make up the smallest section of EU’s energy mix even when you add in biofuels which are hugely carbon-intensive…

In fact, even despite the coal phaseout the EU was still using as much coal-generated power as renewable generated power…. On top of all of this, we must remember that electricity is only a fraction of the power consumed by Europeans. In 2022, it was just 23%.”

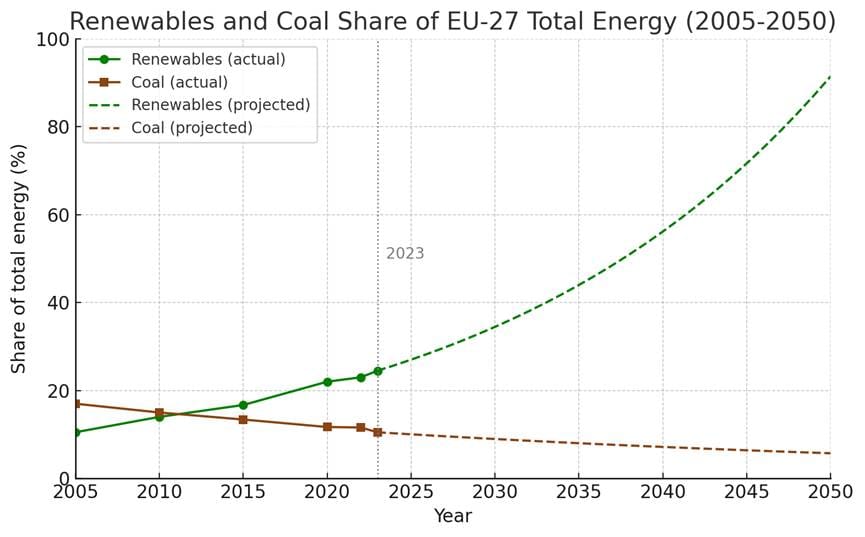

These stats firstly reinforce my point that the EU is experiencing an energy transition, and secondly that this transition is only just beginning to take off. Coal’s share of energy in the EU in was 27%. This has plummeted over 35 years to 14%, with renewables now competing at the same level in that time frame. This is evidence of an ongoing technology disruption. It is not yet complete, and we’re only at the beginning of the S-curve of disruptive change.

Yes, renewables are “still the smallest part of the mix”. But the mix is changing! Fossil fuels make up 77% of EU final energy in 2022, but that’s down from 93% in 1990. And that remaining fossil fuel share is shrinking annually. Renewables tripled from 4% to 12% of final energy since 1990, coal’s share fell from 10% to less than 2%, and critically, total energy consumption has been falling since 2006. These are hallmarks of an energy transition in motion. The imperative now is not to deny it’s happening, but to accelerate and improve it.

As electricity is only 23% of final energy now, it will be crucial to accelerate the electrification of the most fossil fuel intensive sectors especially transport and heating.

The interplay between sectors is crucial: electrification is now increasingly propagating to transport and buildings via EVs and heat pumps. The EU has legislated a phase-out of new combustion car sales by 2035, which will start to carve out a visible dent in oil demand. Europe has also embarked on replacing fossil fuel heating with electric heat pumps at a record pace. The sale of heat pumps in the EU jumped nearly 40% in 2022 to reach about 3 million units sold that year.

At the end of this piece, I’ll provide an empirically-validated forecast of where these trends are likely to lead in the EU.

China’s coal use is rising – but slowing because of renewables

Rachel Donald takes issue with my claim that whenever renewables are deployed this bends the curve of fossil fuel use downwards. She points to China as the definitive proof that this is false, but my argument is precisely that in China the renewable energy transition is underway and not yet complete, but is indeed bending the curve of fossil fuel growth. This is on track to lead to decline. The process has already begun - the International Energy Agency has forecasted an approaching coal plateau enabled by China’s accelerating deployment of renewables.

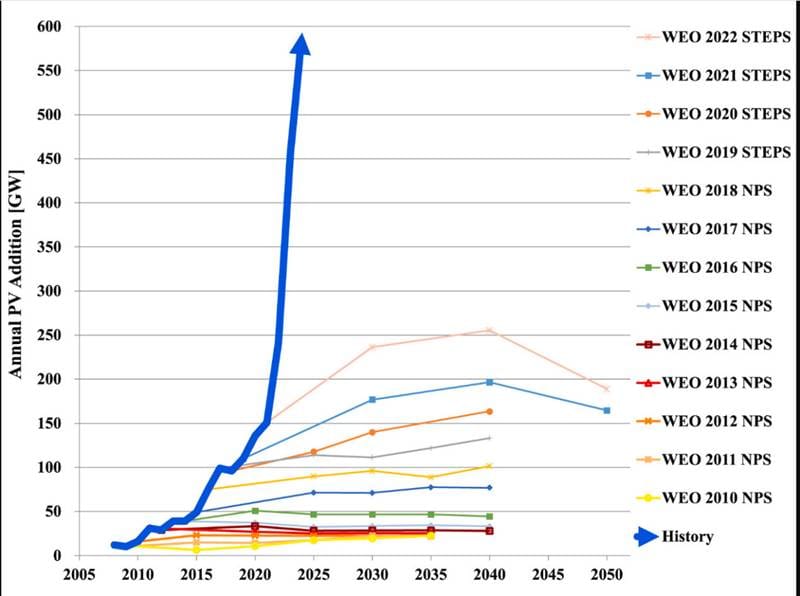

Twenty years ago, naysayers were saying that renewables would never be able to scale and compete with fossil fuels. Just look at the IEA's previous flawed forecasts of renewables every year in that time-frame.

In hindsight, clearly it would have been mistaken to point to the data twenty years ago to say definitely that renewables do not bend the fossil fuel curve downwards. Back then, they hadn't because the transitions were too early. Now, we can see more clearly how this is starting to happen in the US, UK and Europe.

Donald is right that, so far, China’s renewable surge hasn’t caused a sharp drop in fossil fuel consumption – but it has slowed down the growth. In March, the IEA noted that “demand for the most widely consumed oil-based fuels – including gasoline, jet fuel and diesel” in China had “declined marginally in 2024. What’s more, China’s combined consumption of these fuels of almost 8.1 million barrels per day (mb/d) was 2.5% below 2021 levels and only narrowly above those in 2019.”

Climate Action Tracker finds that while China’s emissions are at an all-time high, “thanks to the rapid rollout of renewables and a significant reduction in new coal power projects,” China’s emissions might peak in 2025. That doesn’t mean it’s all hunky dory. Continued energy demand growth could derail this progress, and as Climate Action Tracker points out, the pace of change is still “highly insufficient” in addressing climate change.

The issue is not that the energy transition is a myth. This is a red-herring. The issue is that it’s happening too slowly, and there can be no doubt that Donald is right to point to barriers inherent to capitalist structures which could be obstacles to the transition.

To underscore this, a new study in Energy Sources forecasts that at currently accelerating deployment rates:

China’s total energy demand could potentially be met by a combination of all renewable energy sources – including hydropower, solar, wind, geothermal, and nuclear energy – around 2064.

It forecasts that:

China’s renewable energy consumption will reach 56% by 2050 and 98% by 2060 respectively.

This means that there is a direction of travel – but it’s not fast enough to bend down the emissions curve to avoid dangerous climate change. The issue is not that it can never happen, but that it is not happening fast enough. And the answer need not be polarising: accelerating deployment of renewables while seeking to reduce economic demand through fundamental economic change (whatever that might need to look like) are surely both going to be crucial to accelerate and deepen the bend.

What next for Europe?

In the mid-2000s, renewable energy made up only around 10% of the EU-27’s total energy consumption. By 2023 this share had reached 24.5%. In other words, renewables’ share of the energy mix has more than doubled since 2005. This represents a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 5% over that period.

Assuming this exponential growth rate continues, renewables would command an increasingly dominant share of the energy mix by 2050. Projecting forward at 5% growth annually, the renewables share would rise to 80-90% by 2050 (approaching a fully renewable energy system).

By contrast, coal’s role in the energy mix has steadily declined. In 2000, solid fossil fuels (mostly coal) accounted for about 18.6% of EU energy supply. By 2022, coal’s share had fallen to only 11.6% of total energy. This long-term decline reflects the phase-out of coal in many countries and replacement by gas and renewables. Over 2005–2023, coal’s share dropped roughly 2–3% per year (compounded) on average. Absent any major policy change, this steady phase-out trend is expected to continue.

If this historical rate of reduction persists, coal’s share would continue to shrink exponentially. The brown dashed curve below projects coal at about 5% of the energy mix by 2050.

The 5% CAGR for renewables reflects factors like cost reductions and pro-renewable policies. To reach near 100% renewable by 2050, which arguably is already far too slow, a similar or even higher growth rate would need to be sustained. In fact, the EU’s updated targets (42.5% by 2030) would require roughly 8% CAGR from 2023–2030, nearly double the historical rate – a challenging acceleration.

This is likely a conservative projection. Coal’s steady decline is projected as relatively slow. In reality the amplifying feedback effects between the growth of renewables and the decline of coal are not represented here. Those feedback effects mean that as renewables scale, they will increasingly take up the demand previously met by coal and therefore accelerate the decline of coal. But even if that system dynamic is ignored, the simple projection above demonstrates that renewables are on track to dominate the EU energy system by mid-century.

Already have an account? Log In

The problem is that this transition is still too slow, and could also be further derailed with regressive old paradigm policies designed to cling to incumbent industries and interests.

I should be really clear about what this means. A renewables disruption can potentially end fossil fuel consumption, but by itself it cannot end the predatory structures of the economy. And it can also be dangerously delayed by the regressive incentive structures in that economy. This is a problem because if those do not change, then the imperatives of capitalism will incentivise destructive and predatory growth dynamics in which renewables reinforce destructive ecological pressures. Equally, fossil capitalism creates distorted market dynamics which create barriers to renewable energy adoption. Given the relentless dynamics of past technology disruptions, while those barriers are unlikely to be able to prevent renewables from disrupting fossil fuels, they could potentially delay the energy transition such that it cannot avoid catastrophically dangerous climate change.

This business as usual trajectory could lead us towards a scenario over the next decades in which the emerging renewable energy system is deployed tepidly and sub-optimally while the fossil fuel system enters a spiral of catabolic collapse, amidst a context of escalating climate tipping points.

Net zero mining?

Unfortunately, Rachel Donald is dismissive of the idea of scaling renewables in such a way that we can power a true circular economy. She suggests that the technology does not exist. This is incorrect. We can already now recycle batteries and solar panels with 99% efficiency, for instance. Up to 35% of manufacturers in the US could power themselves entirely just with rooftop solar. Solar thermal technology that can provide heat for heavy industry is already here.

Part of the main obstacle to harnessing the full potential of renewables to power industrial manufacturing is precisely that they have not been scaled up. In a 100% renewable system, as I explained the piece, the system possibilities look quite different and yes, the prospect of powering the manufacturing of renewables with renewables no longer seems impossible. Indeed, the possibility of leveraging renewables to power a full circular economy is not just a strange notion conjured up by a fevered imagination, but a feasible technological possibility that has received rigorous study. Viable strategies to attain net zero mineral demand by 2050 have been laid out by the Rocky Mountain Institute - none of these strategies are especially fantastical from a technical point of view.

In the meantime, we’ll need to rapidly scale up the 7 million tonnes of materials we mine today for key minerals for the energy transition by four times to about 28 million tonnes a year out to 2040. This is a lot. But it’s 535 times less than the 15 billion tonnes of materials we extract in the form of coal, oil and natural gas that we will be able to put an end to. A global renewable energy system will, therefore, reduce mining dramatically.

Of course, I share Donald’s concerns about the predatory exploitation of environments and communities in pursuit of mining of different materials. Within the structures of neoliberal capitalism and a paradigm of self-maximisation through endless materialist consumption, the risk of intensifying this mining for profits in contempt of fundamental ethical values is high. That is another reason technology alone is not enough; we also need an economic and organisational paradigm shift which recognises the value of protecting people and planet, and enshrines that into the way businesses operate. This is a shift that is starting. The challenge is to scale it and transform.

Pick your fantasy

I was struck by Rachel’s comment here: “… basing the future of human civilisation on technologies which aren’t at scale - or don’t exist at all - is harmful.” She argues that we need to “dismantle the economic system which exploits power to steal resources to create wealth for some and poverty for many”. How likely are either of these?

It’s easy to look at the future and describe ideas about it as fantasy. If Jean-Baptiste Fressoz’s thesis in More and More and More were correct, one might be forgiven for assuming that dismantling the patterns of endless extraction is a fantasy. It’s all we’ve ever done and known as a species. Someone might observe: Basing the future of human civilisation on an economic vision which not only doesn’t exist, but has never happened before in human history, is harmful.

Ultimately the logic offered by both observations is flawed because the assumptions are wrong. The idea that we shouldn’t work to create a future because the things in it haven’t scaled yet is basically saying that because it hasn’t scaled we shouldn’t scale it. By the very same flawed logic, because no one has managed to dismantle the economic system at scale, then suggesting we base our future on this idea is harmful and we should not attempt to dismantle it at scale.

I would also caution: “dismantling” something is not a vision. It’s a negative and, sure, justifiable diagnosis of our predicament. But what are we for? What are replacing the old paradigm with? What does the new paradigm look like?

We are moving into a liminal space of fundamental uncertainty as the old paradigm weakens and breaks down.

Systems thinking allows us, for the first time in this context, to examine the incredibly complex dynamics of the various energy, economic, environmental and other systems we find ourselves in, and to discern the patterns by which they move through their life-cycles of growth, stabilisation, decline and renewal.

One of the things we can see is that as the fossil fuel system enters a state of turmoil and decline, new energy technologies are emerging. One of the things we can see is that as capitalism enters a state of turmoil and decline, new models of economic organisation are emerging. We need to scale up both, together.

There are some who might “lionise” renewable technologies as a way to ‘save modernity’. That view, however, is not grounded in a full appreciation of the mutually-constituted nature of technology and culture. It is fossil capitalism in its entirety that is in crisis. Scaling key renewable energy technologies with their distinctive system dynamics cannot maintain the incumbent paradigm, and attempting to do so will result in self-cannibalistic collapse. That is why we also simultaneously need to transform the organising system by which we manage the emerging new production system.

But this does not entail jettisoning modernity. It entails transcending it.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In