One of the first things Donald Trump did after coming into office for his second term was to promise to "unleash" oil and gas drilling, ostensibly to bring down costs and secure American energy independence.

On 4 March, the White House released a memo titled "President Trump is Unleashing American Energy" outlining the blitzkrieg of actions taken to date, including establishing the National Energy Dominance Council to "maximise use of America’s extensive energy resources"; clearing the way to open up oil and gas resources in Alaska, and reviving environmentally-destructive offshore drilling on American coastlines. Simultaneously, the US government paused federal permitting for hundreds of major solar and wind projects across the country.

The pretext for this is that clean energy and 'net zero' are what the White House calls the "Green New Scam", ripping off "our country", undermining "American consumers", "killing" American jobs, and beyond.

In reality Trumpocracy 2.0 is fighting a war to shore-up a dying fossil fuel industry whose time has come. The entire country and the planet is to be sacrificed to protect the profits of American oil and gas majors despite the industry offering up diminishing energy returns.

Trump's fossil fuel obsession dovetails with a new strategy of barely concealed imperialist expansion. Trump's Ukraine plan is a blueprint for the total conquest of the country's mineral resources including potentially fossil fuels; Trump's Gaza plan is a de facto settler-colonisation project premised on property development but also includes the Gaza Marine's untapped gas resources; Trump has doubled-down on the notion of annexing Canada, with its own massive mineral and fossil resources, as a "51st state"; Trump wants to take control of Greenland which has extensive fossil fuel resources; Trump wants to "take back" control of the Panama canal a major transit point for fossil fuels; Trump wants to drill like crazy in Alaska which has considerable fossil fuel reserves.

Many observers wonder about the realism of these crazed announcements. And to be sure, they are not 'realistic' in the sense of viable plans that would actually work. But it would be a mistake to presume that this means they are not deadly serious. In fact, these plans make sense in the context of a looming systemic crisis facing America's fossil fuel industry.

The ongoing US fossil fuel slowdown

Two weeks before Trump took office in 2025, the British multinational banking conglomerate Standard Chartered published its bleak diagnosis on the near-term fate of US oil production.

The "dramatic slowdown in US" oil production growth that we witnessed in 2024 will continue over the next two years" predicted the bank's commodity analysts:

According to the experts, last year witnessed a sharp slowdown in non-OPEC+ supply growth from 2.46 mb/d in 2023 to 0.79 mb/d in 2024, primarily caused by a reduction in U.S. total liquids growth from 1.605 mb/d in 2023 to 734 kb/d in 2024. StanChart expects this trend to continue, with U.S. liquids growth expected to clock in at just 367 kb/d in 2025 before slowing down further to 151 kb/d in 2026.

In recent years, a growing number of oil industry experts and mainstream financial observers - including the Wall Street Journal and Forbes - have acknowledged that US shale oil and gas production seem to be approaching a peak in coming years. Despite considerable disagreement among experts, there is an emerging realisation that the American shale revolution is slowing down - and along with it, the prospects for continued American energy expansion.

From 2019 through about 2021, analyses varied widely on shale’s trajectory. Some, including government forecasts, confidently projected rising output well into the 2030s, whereas a handful of contrarians argued a peak was looming by the mid-2020s. This led to a mixed narrative – optimism in official circles, scepticism among a few analysts attuned to shale’s physical limits.

Today a majority of expert commentary accepts that geological and economic realities are catching up. By 2022-23, even oil industry veterans like Pioneer's Scott Sheffield and Occidental's Vicki Hollub were publicly cautioning about impending production peaks.

The Permian basin is going to "peak in 5-6 years" warned Sheffield. "It’s going to start to roll over, and when that happens, that’s when the US is at risk for losing our energy independence," said Hollub. "That could come in the next five years that we start to see that plateauing happen." According to data from Conoco Phillips, drilling inventory estimates suggest that the core of the Permian could be mostly tapped out within a decade.

It’s notable that these figures come from industry sources – they are not far-off doomsday predictions, but internal industry estimates that acknowledge a rapidly closing runway.

US oil production has, for all intents and purposes, flatlined since 2021. From 2021–23, the average annual US oil growth has been only 0.5 million barrels per day (bpd). Even as production has increased, the rate of growth is clearly decelerating.

In 2025, executives at a major 2025 industry conference projected that Permian output will rise by only 0.25–0.30 million bpd in 2025, down from a 0.38 million bpd increase the year prior. Even if US shale continues to be squeezed out at higher levels through the next decade, the fact that the rate of growth is slowing down in only one direction of ultimate decline is no longer in question. US shale is no longer in hyper-growth, and multiple indicators (stagnant non-Permian production, slowing Permian gains, lower well productivity) point to a looming plateau.

How the fundamentals reveal that shale is coming off the rails

Shale wells are yielding less oil per well over time as operators exhaust the “sweet spots.” Analysts note that the huge early gains in productivity were driven in large part by high-grading – drilling the best rock first – rather than limitless technical improvement.

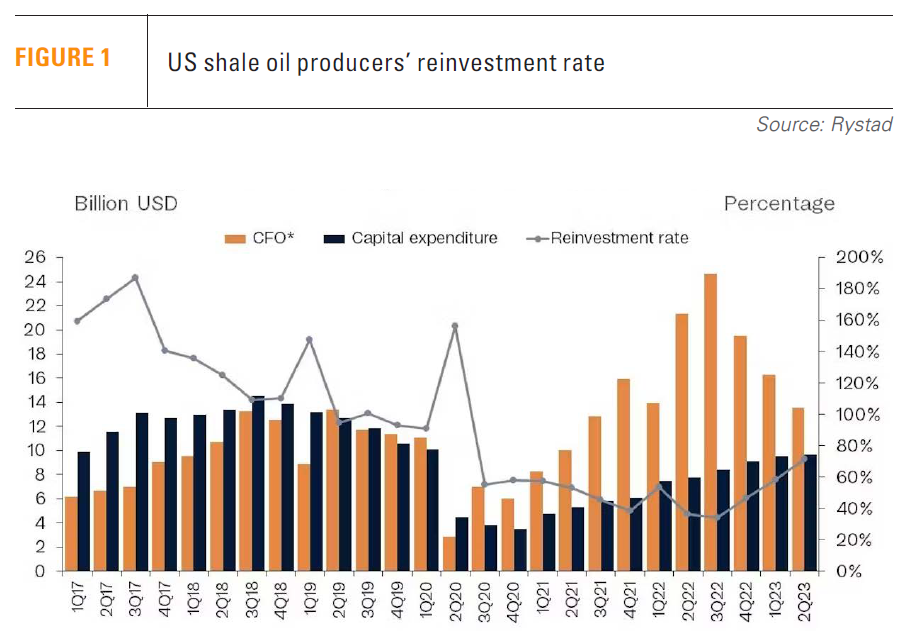

Shale producers are no longer 'disruptors'. They are now acting like incumbents, focused on controlling costs, increasing profit margins and returning capital to shareholders - at the expense of continued drilling and production growth.

The result is chronically underinvested drilling programs: “Drill, baby, drill is not going to happen,” as one oil executive succinctly put it in early 2025. Even when oil prices spiked in 2022, US producers only grew output modestly, opting to boost dividends and buybacks instead of ploughing money into new wells.

Even as technology has improved, inflation in oilfield costs has driven up prices for steel pipes, labour, fracking sand, and equipment. In 2021–2022, for instance,. shale operators faced 10–20% increases in drilling and completion costs. The Federal Reserve of Dallas's energy surveys in 2021 showed cost indices at their highest in years. This is a long-term trend - the cumulative cost of US oilfield services has risen substantially from 2000 through 2024, driven by volatile oil markets and industry activity. This has eroded profit margins and raised the oil price needed to justify new projects.

Which is partly why rig count and frack crew count have been in decline since early 2023. By mid-2024, the US oil rig count had fallen about 15% from its post-Covid high, even as production inched up – a clear sign of producers holding back on new drilling. Fewer rigs and frack spreads today mean less new oil tomorrow without further investment - and that investment is dwindling as drilling gets more expensive and less productive.

There will be continued technological improvements, but the gains from these will yield diminishing returns. This is already visible. The most impactful innovations that opened shales up have already been deployed. By late 2010s, location quality was the biggest driver of well output, not drilling technique.

This doesn't mean technological innovation can't keep the show going for a while longer - but it's a double-edged sword. New aggressive techniques that maximise short-term output (like extreme frack designs) can increase production at the expense of draining regions faster, hastening field-wide declines. While continued improvements in technology can be expected to prolong production for some years, it cannot repeal the laws of physics in the reservoir. There is no major new technological breakthrough coming on the horizon. Absent such a revolutionary breakthrough, technology will likely slow the decline but cannot prevent it.

This means that Trump will not be able to significantly increase US shale production. It also means that his efforts to maximise fossil fuel production are being pursued in recognition of a stark fact: the industry is approaching an inflection point. And they need massive state intervention and subsidies to keep the show going, profits rolling and companies solvent.

Conquering far-flung places like Alaska will not solve this. Alaska, for instance, is not near-cycle shale production - and would require years of development. There's no guarantee that it can meaningful offset the coming plateau of US shale. Can US natural gas act as a bridge fuel in this context? As shale oil declines, hopes to export US gas will be dashed by growing domestic demand, which will be challenging given that shale gas appears to be also declining.

The bigger problem - haemorrhaging returns from fossil fuel energy

Underlying America's looming energy crisis is the reality that the energy returns from fossil fuels have been declining over the last 75 years, if not longer. There is now a fairly strong scientific literature on the concept of Energy Return On Investment (EROI), which measures the amount of energy inputted to extract energy out from a given resource.

One fascinating addition to this body of work was published in December 2024 in the form of a Masters thesis titled, The Rise of Inefficient Energy- Are Gross Estimates of Fossil Fuel Production Hiding Declining Net Energy in Society, by Kai Ferragallo-Hawkins at the Programme on Contemporary Societies at the University of Helsinki.

Ferragallo-Hawkins' pulls together reams of extensive data, but his most crucial finding is pretty simple: fossil fuel production can continue to increase, but in doing so this increase conceals a cannibalistic net energy decline, the costs of which are borne increasingly by society and the wider economy.

This, he shows, is exactly what appears to be happening to the global economy already - and will increasingly define a future of continued fossil fuel dependence. The EROI for oil (often measured together with gas) has declined dramatically over the past century. Early in the 20th century, conventional oil extraction yielded very high EROIs (on the order of dozens to one, with some estimates for US oil and gas around 100:1 in the 1930s) . This has fallen to low double-digits in recent decades – for example, one analysis indicates US oil and gas EROI dropped to roughly 11:1 by the mid-2000s. Overall, the evidence shows a clear decline in oil and gas EROI over time, meaning it now takes significantly more energy investment to produce the same amount of fuel than it did a few decades ago.

Using a supply-side model combined with an empirically-informed EROI function substantiated by the work of Victor Court and Florian Fizaine, the thesis projects that oil’s EROI will continue its downward slide from roughly 10:1 today to about 4:1 by the late 2060s, and around 2:1 (half of output consumed in production) near the end of the century.

Coal's EROI is shown to decline even more rapidly under this model’s “base” scenario, falling to 10:1 as soon as the 2030s and to around 4:1 by the 2060s, reaching a similarly dire 2:1 net energy ratio by 2090–2100.

Natural gas is the last fuel standing, plateauing at about 10:1 until the 2070s before declining more slowly and reaching 4:1 by the 22nd century.

Overall, the long-term trend is one of inexorable EROI decline: all fossil fuels head toward the low single digits over the next 50–100 years. This means, according to the thesis, that the gap between gross energy produced and the net energy available to society will continue to widen steadily in the future.

The model generates two curves: one is a gross production trajectory. The other is a corresponding net energy trajectory which subtracts the energy cost of obtaining it through extraction, refining and transport. By comparing these two curves, the thesis highlights the hidden gap that emerges when energy quality declines. The gap widens exponentially as EROI declines with a consistent pattern: the share of gross energy that must be reinvested into production roughly doubles every quarter-century.

This has stark implications. Oil industry data looks only at gross production data, but not at net energy. When we do the latter, the peaks of usable energy occur sooner and the declines are steeper. Societies will see stagnant or falling net energy availability decades earlier than gross production peaks.

The beginning of the end

A simplified scenario in the thesis shows how US liquid fuel net output could stagnate in the 2030s and start declining in the 2040s, even while official gross production still rises – purely because of the EROI downturn. This underscores the risk that optimistic production forecasts are overestimating actual net energy supply by systematically ignoring the declining efficiency of energy extraction. The thesis quantifies this gap, and concludes that there will be a widening gulf between energy produced and energy available for use.

Given that the technological innovations that enabled fossil fuels and large EROI levels allowed us to reduce the roles of land, capital and labour in energy production over time, as EROI declines this will reverse - more workers, money and infrastructure will need to be absorbed simply to keep sustaining energy production. Similarly, as EROI declines, in order to keep energy production going, more energy will be needed to keep producing fossil fuels which will reduce the availability of energy for society, the economy and other public services. In other words, this will have a cannibalising effect, where the very survival of the fossil fuel energy system becomes parasitical on society.

This is where the model runs into some trouble because it assumes that as EROI declines, this will result in a form of 'energy sprawl' in which more and more human labour is needed to prop up the energy system. This, however, is not a viable possibility for simple technological reasons. The fossil fuel infrastructure has grown and expanded on the basis of drilling technologies which by their intrinsic design have reduced the need for human labour in energy extraction at multiple points compared to the pre-industrial age. There are no viable mechanisms to expand oil production using these technologies by inserting more humans into the process.

This means that in reality, the more EROI declines, the greater the costs to society - the greater the inflation, the greater the subsidies, the greater the borrowing and the more the fossil industry will need to leech onto the power of an increasingly authoritarian state. Instead of a reversion to human labour, which the model incorrectly assumes will be the way 'energy sprawl' manifests as EROI declines, this will need to manifest in a need a range of expansionist strategies to generate the investment needed to sustain continued production.

Many of these strategies are what we are seeing in the Trump administration - attempting to identify new sources of fossil fuel production (from offshore to the Arctic to Greenland to Canada to Ukraine); an increasing fascist consolidation between the state and private enterprise in order to secure guarantees of perpetual government backing; leveraging state and government military power to acquire these new sources of production, and to squeeze out sources of competition which threaten fossil fuel dominance.

The problem of course is that these strategies cannot ultimately work - they are reactive attempts to shore up the profits of the most powerful fossil fuel companies while that resource base declines. This has created a bizarre dynamic: the very inflated profits of the fossil fuel industry due to rising prices as net energy declines keeps oil and gas a sought after investment for immediate returns. The market does not detect the underlying system dynamics at play. Inflationary effects in the economy which spike commodity prices but especially fossil fuels provide the industry with the economic cushion it needs to continue operating.

But there's a point at which the cannibalistic effect will inevitably fatally undermine operations. That's because the same inflationary effects which drive up oil and gas prices and temporarily buoy profits also drive up costs across the whole economy - including the costs of continued oil and gas production in particular. Technological innovation, whose returns are diminishing, is becoming less and less effective at offsetting the inflationary impact on oilfield services costs.

And that inflection point is arriving. In January 2025, Rystad Energy observed that growth in the oilfield services industry since 2022 was now levelling off, forecast to shrink by 0.6% this year - driven by "inflation, capacity constraints, and geopolitical factors". Ironically, Trump's tariffs policy could double the costs of essential equipment for energy production, Rystad warned.

This is when we begin to see that a collapse process is setting in: when the very strategies you feel compelled to deploy to sustain the system, end up cannibalising that system, and accelerating its plunge into terminal decline.

In 2023, I warned that the American fossil fuel economy was sleepwalking toward collapse. This will have seismic consequences not just for the United States, but for the global order - which is already being torn apart at the seams by a rampant US government hellbent on remaking this order to keep a dying American fossil fuel economy alive.

Trump's imperial presidency is about to preside over a spiral of chaos and crisis. Its expansionist agenda is a function of its ideological commitment to maintaining the economic power of the industries which once brought the US to the peak of power in the world system. But our best scientific data confirms that those industries are now in their twilight.

Back in 2011, in my book A User's Guide to the Crisis of Civilization: And How to Save It, I warned that the convergence of multiple systemic crises across industrial civilisation would drive processes of state-militarisation in the absence of transformation. That's because systemic crises tend to undermine the prevailing fabric of norms and values which hold a society together and underpin the legitimacy of prevailing political orders. As systemic crisis deepens, then, this tends to drive a process of Otherisation - and at the state level this often shows up as a hardening and centralisation of state power, resulting in a resort to increasingly authoritarian forms of militarised social control.

Say hello to Trumpocracy 2.0.

Something else I've pointed in my new book ALT REICH: THE NETWORK WAR TO DESTROY THE WEST FROM WITHIN, is that state-militarisation doesn't actually work as a response to systemic crisis. You cannot exert control over collapse - you can only move through it to the other side by transforming the system itself. This means that the rapid militarisation we are seeing spearheaded by Trumpocracy 2.o will not offer anything meaningful. It will accelerate crisis, and in the process it will undermine its own power. Just as the rise of the Alt Reich took most by surprise (I predicted it 15 years ago), the collapse of the Alt Reich will likely also come faster than most expect.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In