Artificial intelligence (AI) is going to change the world, but exactly how remains hotly contested. Most commentators including AI insiders have, however, overlooked the real issue:

The explosion of chatbots like GTP-3 and GTP-4, along with diverse new applications related to numerous industries and sectors, has suddenly thrust artificial intelligence into the spotlight. The surprising capabilities of these new AI tools – from analysing and processing vast amounts of information, generating complex works of art and photorealistic images, to high-level coding – is already surpassing human capabilities in these domains.

The rapidly unfolding AI disruption has taken the world by shock, sparking new debates about the nature of human intelligence and consciousness, the social and political consequences of exponentially improving AI capabilities, and concern that AI will wipe-out millions of jobs.

And nearly every other day we hear from AI industry founders and insiders describing their fears that existing AI tools could be merely primitive precursors to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – God-like AI superintelligence – which would move out of human control and potentially even wipe out humanity.

If you haven't already, you'll want to check out my previous post where I dug deep into the current evolution of AI and revealed that fears of AGI are premised on false assumptions about the nature of human intelligence, and the way that natural language processing models actually work in relation to human intelligence. I found that contrary to widespread claims, AI remains fundamentally narrow in scope, is nowhere near replicating human reasoning in the form of abductive inference, and that there’s little evidence AI can replicate human intelligence - which is not confined to IQ and the brain’s computational power, but is inherently collective and civilisational.

I warned that the real existential threat from AI is its abuse within centralised structures of power to magnify the weaponisation and manipulation of information flows in the interests of narrow vested interests, at the exact time when we face an unprecedented convergence of energy, economic, environmental, geopolitical and cultural crises.

In this post, I take an even deeper dive to explore what AI really means, what’s driving it, and the new possibilities it represents. There's a lot to digest here, but the implications are enormous. Here's a summary of my key takeaways:

1. Information is not only one of civilisation's five foundational systems of production, but it's one of the prime motors of history. The evolution of human civilisation throughout history was driven forward by breakthroughs in information technology which allowed civilisations to reach new scales. This suggests that the rise of AI is a precursor to an entirely new phase for civilisation. I'll use the concept of the global phase-shift to make sense of what this means.

2. Humanity appears to have moved through four significant revolutions in information with major civilisational implications: firstly, the invention of writing; secondly, the invention of the printing press; thirdly, the invention of digital computing; and fourthly the invention of the internet. We are now moving into the fifth phase, driven by the invention of artificial intelligence. The rise of AI therefore suggests we are moving into a new era for humanity that like previous information revolutions will completely redefine human civilisation.

3. The disruptive consequences of AI can be predicted on the basis of empirical data from technological cost-curves. These reveal exponentially declining costs and exponentially improving capabilities in narrow generative AI out to 2030, which like previous disruptions will therefore drive exponential mass adoption along S-curves over this period.

4. Mass adoption of AI will, as with previous information revolutions, generate cascading second and third order effects. There is compelling evidence showing how AI will have revolutionary impacts across all other major sectors of the global production system encompassing energy, transport, food and materials, which will accelerate existing technology disruptions in these sectors, while also driving new convergences that spark further disruptive innovations creating new business models and value chains.

5. One of these disruptions in particular – the autonomous vehicle disruption in transport – will generate the key sensor, modelling and navigation technology architectures applicable across the key industrial sectors associated with manual physical labour. This suggests we will begin to see the rise of automation disrupting manual labour shortly after the AV disruption – it could start as early as around the mid to late 2030s.

6. The coming AI disruption will be unstoppable and all-encompassing (bar a major global catastrophe). However, understanding its implications correctly suggests two major potential scenarios when understood through the lens of the global phase-shift: at worst, a societal regression that sees AI amplify the most regressive structures of incumbent centralised systems of power; at best, a new possibility space for mass distribution of economic abundance premised on collective intelligence within a transformed social, economic, political and cultural organising system.

Information as a breakthrough technology

Information is one of the five foundational systems of production within human civilisation. How we produce, process and disseminate information plays a fundamental role in defining the way a society works.

Since human beings have existed, we’ve had several major information disruptions through human history that have played pivotal roles in driving the evolution of civilisation. A major study by the Santa Fe Institute looking at over 400 societies spread over six continents and 10,000 years found that once a civilisation reached a certain population size, it would hit an ‘information bottleneck’.

If it failed to develop new information systems – like writing or systems of currency – that could provide a new foundation for the evolution of its governance and organising structures further expansion would stall, and the civilisation would regress or collapse.

The few civilisations that did cross this ‘scale threshold’ did so through major advances in information processing and storage. Information, in other words, is a critical technology that can make or break a civilisation. But it's not information alone - it's how a society harnesses new information breakthroughs to create new societal infrastructures that is the key.

This research suggests that information disruptions today signal how we’re approaching a similar ‘scale threshold’ on a global level that has never happened before in history.

Understanding technology disruptions

Information disruptions in history highlight that the way conventional analysts interpret the interplay between technology and society – extrapolating the present into the future in a straight-line – is deeply flawed. As a result, they often fail to anticipate the full impacts of societal and technological change, which is why the current AI explosion has taken so many by total surprise.

The most robust and empirically-tested framework to understand technology disruptions has been developed by Tony Seba.

A disruption happens when new products and services create a new market which weakens, transforms, or destroys existing products, markets or industries. Disruptive technologies emerge when several technologies converge to make possible entirely new products or services that outperform and outcompete existing products.

Time and again, history shows that the costs and capabilities of disruptive technologies improve exponentially rather than linearly. Self-reinforcing feedback loops between different factors such as investments, research and development, manufacturing scale, experience and learning effects, competition, regulatory standards, market size, and beyond drive disruptive technologies to improve exponentially. These fast rates of technology improvement are reflected in cost-improvement curves.

Technology disruptions throughout history show that when costs decline exponentially, this drives exponential market adoption. As costs decline, the new technology is increasingly taken up across society, following a sigmoidal or S-shaped curve which starts off slowly, then gradually picks up speed before accelerating dramatically. One amazing historical pattern that Seba has pointed out is that when the disruptive technology becomes ten times cheaper than the incumbent, adoption accelerates and the incumbent is wiped out.

So by understanding the technology cost curves of the disruptive technology, we can predict when the disruption will take place with good accuracy.

It’s also important to appreciate that disruptive technologies are not one-for-one substitutions that simply replace older technologies in the same system. They bring with them completely new behaviours, properties and dynamics that entail entirely new rules: in short, a new system. In the language of systems theory, this means that they bring about a ‘phase transition’ within that sector.

Disruptions are also by their very nature not silo-ed within any one sector. That’s because they are the emergent result of different technologies converging from across different sectors. And they then tend to have cascading effects across other sectors. This means that they not only change the system within their own sector, they end up driving changes across different sectors. Those changes can often then, in turn, feedback onto the original technology.

These process can be seen at work throughout human history across many sectors. Here, we're going to focus on how they've unfolded in terms of information.

Information at the dawn of civilisation: The invention of writing

As Arbib and Seba explain in Rethinking Humanity, around 3,500 BCE, at the dawn of human civilisation, one of the most important innovations in history was writing (cuneiform):

“By preserving information, it enabled the improvement of all other technologies. The original Farmer’s Almanac contained instructions on the best way to plant, irrigate, and care for crops. Sumerians invented measurements for land (the iku – which begat the acre) and time (60 second minutes and 60 minute hours). New models of thinking emerged that better explained the world around them, helping to underpin ever-more complex and far-reaching technological and organizing capabilities. These advances enabled the Sumerians to break through the capability frontier of the previous order and sustain cities of tens of thousands of people.”

The invention of writing was therefore the First Great Information Disruption. It played a crucial role in humanity’s transition from hunter-gatherer communities to the earliest forms of civilisation.

For thousands of years, writing was restricted to manuscripts produced in slow and painstaking ways. As such written communication was monopolised by elite groups. For hundreds of years, this structure stifled the scope and structure of human societies, keeping knowledge largely restricted from wider society.

Information at the dawn of the Enlightenment: the printing press

This all changed with the invention of the printing press, which heralded the Second Great Information Disruption.

In Europe, the information monopoly was closely associated with the social authority and political hegemony of church and state. As Arbib and Seba explain in Rethinking Humanity, that monopoly was disrupted by the invention of the printed book in the 1400s, leading manuscripts to become obsolete in decades.

The printing press came about due to a convergence of technologies across the materials, information and food sectors: metal, movable type, paper, new inks and an adapted wine press. It led to the cost of book production becoming ten times lower than before, making information cheaply available to a general audience for the first time in human history.

The loss of control over information by church and state permitted the mass transmission of ideas. This paved the way for a series of cultural and ideological revolutions including the Reformation, the separation of church and state, the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. This revolution in ideas played a key role in the emergence of a new understanding of reality, and with it, new visions for social organisation that were able to harness the Industrial Revolution.

Medieval governance structures could have never managed the new world that was emerging. As the industrial model began to expand and outcompete others, so too did the new visions of reality, society and values enabled by revolutions in ideas that followed the invention of the printing press.

Information and the birth of global education as a right

The emergence of a global recognition of education as an essential societal resource was indelibly linked to this context of expanding industrial societies requiring an educated labour force.

Before industrialisation, education as a public good was a largely non-existent concept, with learning concentrated among the highest echelons of society – and often monopolised in a way that perpetuated entrenched social hierarchies.

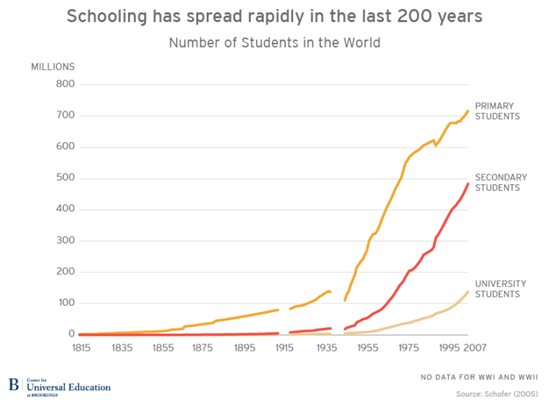

For thousands of years – most of human history – education was the privilege of a tiny elite. But today, most countries in the world recognise education not only as a right, but as a duty enshrined in law to ensure that all citizens attain a basic level of education. This expansion of education was especially pronounced over the last two centuries, during which the number of children attending primary school globally has grown from 2.3 million in the 19th century, to 700 million today, covering nearly 90 percent of the world’s school-age children.

This global ‘scaling’ of education took place over an S-shaped curve resembling the same trajectory as other technology disruptions in history. Although the overall mass adoption of education unfolded over a near-200 year period, the bulk of the acceleration actually occurred in an extremely short period of time.

From 1945 to 1975 – just 30 years – the number of primary school students rose by 500 million people. This coincides with the dawn of the computer age, with the first multipurpose computer created in 1945. The invention of the electronic digital computer represents the beginning of the Third Great Information Disruption.

Exponential growth in the number of educated people sped-up following the invention of the first computer all the way through to 1975, the year Microsoft was founded. It continued to grow rapidly through to the early 2000s.

Of course, many countries in the world remain left behind. In parts of sub-Saharan Africa like Niger, Chad and Liberia, literacy rates remain below 50% for school-aged children. There are therefore not only continued limits to current global education accessibility related to wider social and economic structures, but there is also immense room for progress even in ensuring access to basic levels of education. Despite these limitations, this global education disruption has accompanied the universal recognition of education as a public good to which all people have a right.

If you're appreciating this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

The internet and the dawn of the Information Age

Civilisational-scale information disruptions have not only consistently played a crucial role in enabling civilisations to breakthrough into new capabilities - their impact has becoming increasingly pronounced since the Second World War, and the gaps between each great disruption is getting shorter and shorter.

The dawn of the information age can perhaps be characterised by the increasing impact and speed of information on civilisation. Exponentially-improving advances in computing power have converged across other key sectors of production in energy, transport, food and materials. Information has become a prime mover in multiple major technology disruptions which have fundamentally transformed the capabilities of human civilisation today.

This exponential growth in computing power culminating in the creation of the global internet in the twentieth century represents the Fourth Great Information Disruption.

The internet laid the foundation for a series of increasingly rapid information technology advances in the form of the digitalisation of financial exchange, disruption of landlines by smartphones, video rental by video streaming, traditional print media by social media and big digital platforms, and so on.

These cascading and intertwining information disruptions have transformed human society and culture at an increasingly accelerating pace. Each of these disruptions has built on convergences between previous technologies, and driven further major disruptive innovations across energy, transport, food and materials. Their common denominator has been to make the mass production and dissemination of information an order of magnitude cheaper and more efficient, such that almost anybody can broadcast text, images, audio and video to thousands if not millions of people – a privilege that was once the sole province of a tiny number of corporate media giants.

Yet this great disruption of industrial information systems has happened within the highly centralised and hierarchical industrial organising system. That’s why despite the economic disruption of information, information flows remain heavily skewed within the new centralised structure of the internet, dominated by big platforms whose content can be weaponised by competing centralised centres of political and economic power in a system that remains extremely hierarchical.

At this point, we can see a clear disjuncture between the expanded scope of information technology at our disposal – illustrated by the exponential increase in the sheer volume of information that is now communicated across the world through multiple platforms – and our actual capacity to coherently process this avalanche of information as organisations, societies and civilisations. The increase in the physical transmission of global information flows has not accompanied an increase in collective intelligence.

This suggests that we have reached a new kind of ‘information bottleneck’ that could prevent human civilisation from crossing a new global-level ‘scale threshold’. This is a different kind of information bottleneck than before that cannot be solved by simply expanding the size of the information flows and storage capacity. Rather, it requires new ways to organise and process information coherently so that it can cultivate enhanced collective decision-making capabilities that allow human beings to move into equilibrium with one another, and our planet.

AI and the next transformation of the Information Age

So the sudden eruption of AI is happening exactly when we are already approaching a global-level ‘scale threshold’. Does AI represent what we need to overcome the current information bottleneck? Or will it make it worse?

Regardless of the answer to that question, the emergence of AI represents the next frontier in an ongoing evolutionary process in the expansion of human civilisational informational capabilities. AI represents the Fifth Great Information Disruption.

Like all previous disruptions, it is being driven by fundamental economic factors resulting in exponential improvement in costs and capabilities. These trends are providing larger numbers of people access to increasingly sophisticated information tools, enabling complex capabilities once belonging to specialists to be cheaply and widely available. That's despite the biggest benefits still being concentrated among incumbent centres of power and wealth.

Technology cost-curves for AI suggest that we’re still only at the beginning of the disruption. Not only will AI’s costs and capabilities improve exponentially in coming years, this will drive exponential adoption and thoroughly transform all areas of our global information systems.

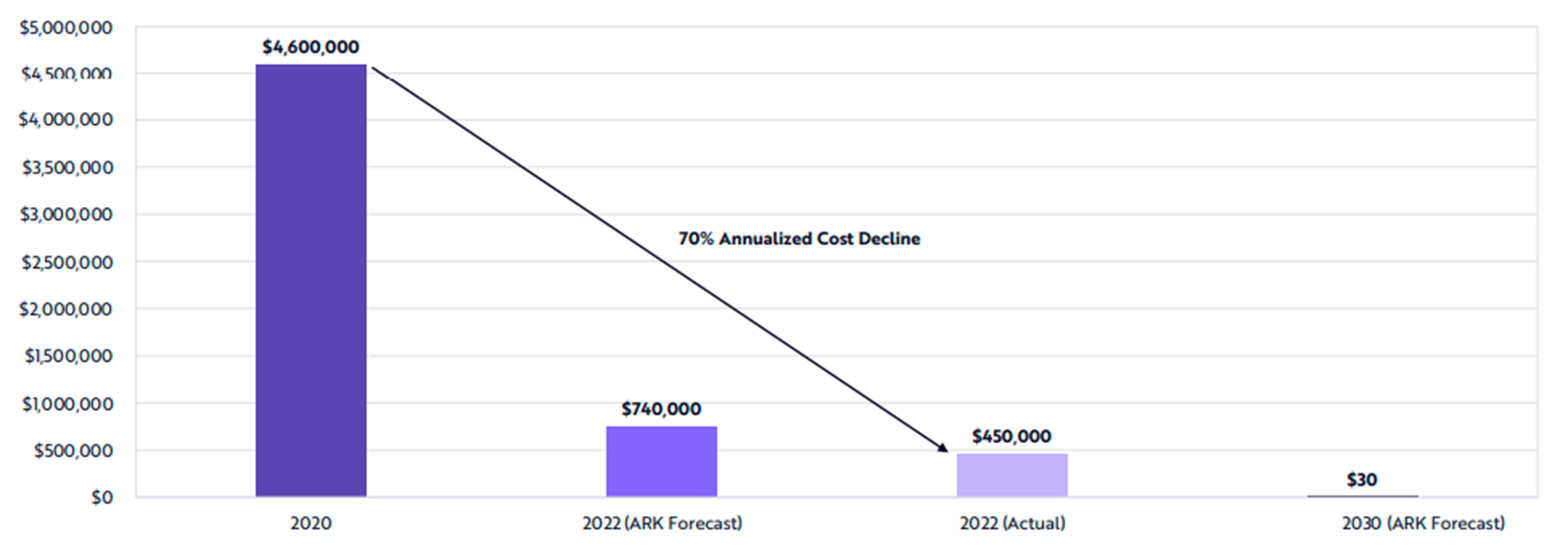

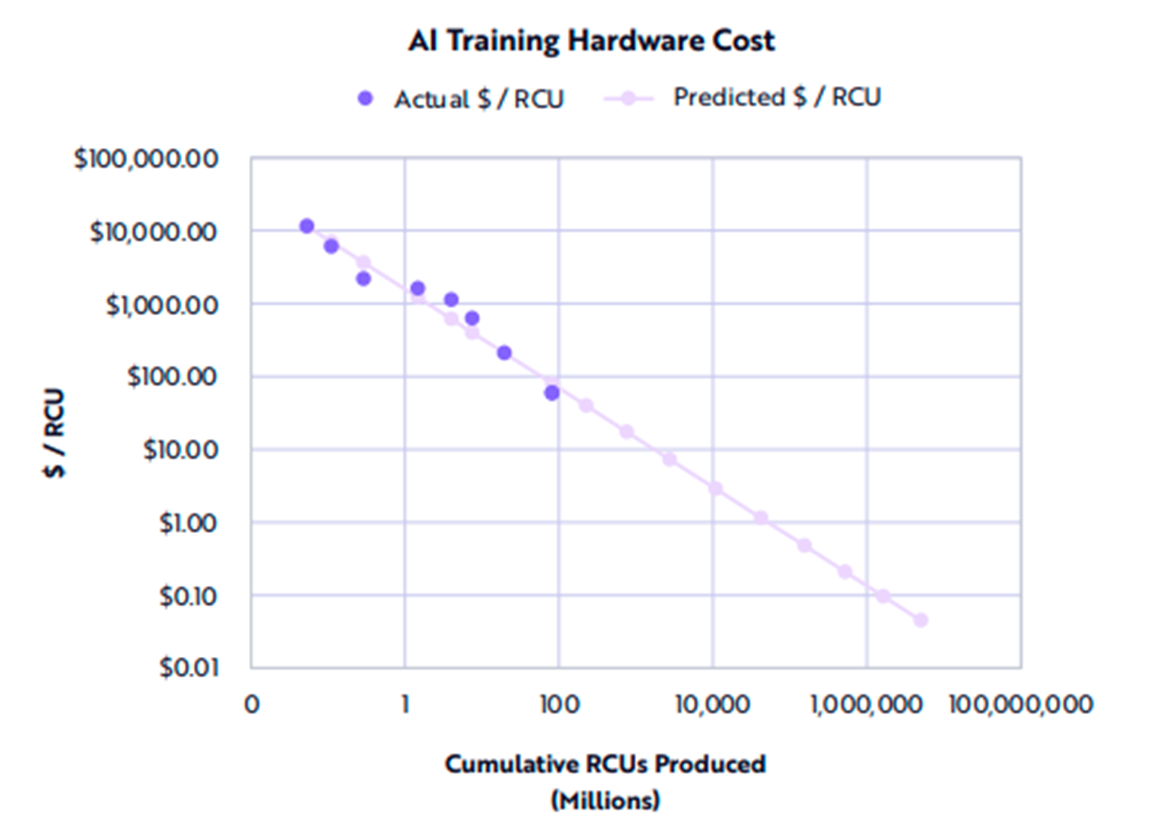

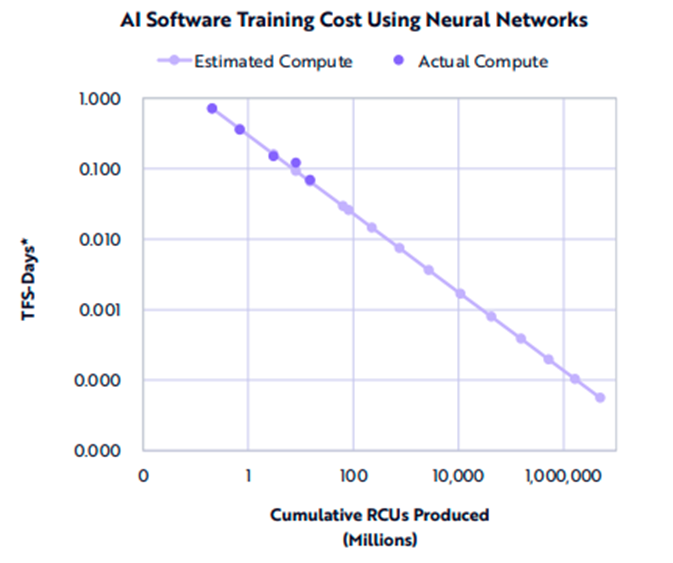

Research published by ARK Investment Management provides some eye-opening data on how technology costs have exponentially declined for major AI applications. Three years ago, ARK found that the cost of training deep learning models is improving 50 times faster than Moore’s Law – the prediction that computing power doubles every two years, which has been applied to many other technology disruptions.

According to the ARK Invest Big Ideas 2023 report, training costs of a language model similar to GPT-3 performance fell by 70% per year from $4.6 million in 2020 to $450,000 in 2022. By 2030, the training cost of a GPT-3 level model will drop further to $30.

ARK also predicts that AI training hardware costs will decrease by 57% every year out to 2030:

Similar massive cost reductions of about 47% annually are anticipated for AI software training costs:

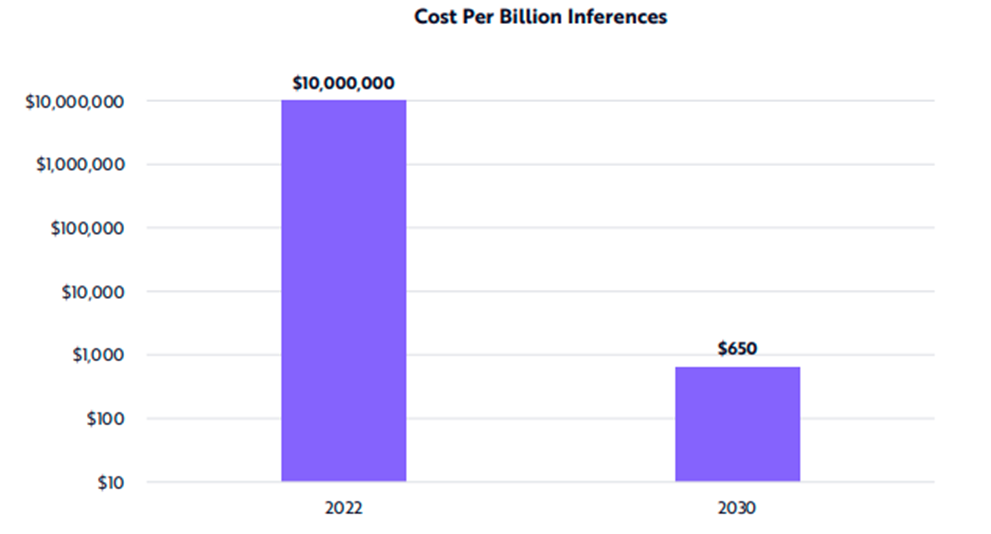

Today, the cost to run an AI language model at scale is about $.01 per query. But this is projected to drop dramatically. Chatbots like ChatGPT will be able to run a billion queries for just $650 – a cost of $0.00000065 per query. And they will capable of processing some 8.5 billion queries a day, which is the number of searches that Google currently processes.

Make no mistake. These technology cost-curves for AI provide stunning empirical confirmation that as the current suite of AI natural language models and related generative AI tools become exponentially cheaper, they will reach mass adoption over the next 10-15 years, in the process transforming every other production sector in the global economy including energy, transport, food and materials.

AI will amplify disruptions in energy, transport, food and materials

These trends mean, for instance, that many key technologies which require massive real-time analysis of structured data will also experience huge cost reductions.

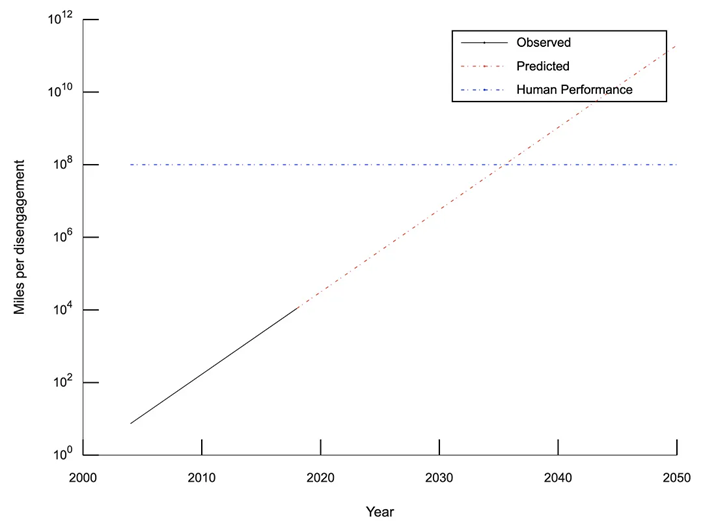

In transport, autonomous vehicle entrepreneur Edwin Olson demonstrated in 2019 that the performance of autonomous driving was doubling every 16 months (in parallel with Moore’s Law). At this rate, full autonomous driving would likely arrive around 2035. But this projection doesn’t take into account the exponential improvements in AI which if applied to self-driving technologies will amplify the cost reductions of analysing even larger datasets – which in turn will likely accelerate the pathway to full autonomy. This suggests that the impact of AI in transport will make autonomous vehicles a reality in the early 2030s.

The impact of exponentially-improving AI will also accelerate the disruption of the food sector by precision fermentation and cellular agriculture (PFCA), technologies which allow us to cheaply create both vegetable and animal proteins (the latter without killing animals), and to do so at ever-reducing costs. The costs of precision fermentation were $1 million per kg in 2000. These have dropped exponentially to $100 and RethinkX has predicted this will continue to drop to about $10 by 2025, which is cost-competitive with the conventional dairy industry, before continuing to get cheaper out to 2035.

AI is already being used to test thousands of combinations of yeast to improve the yield – with costs and capabilities improving exponentially. This will further improve costs and capabilities of PFCA even faster than is already happening. This suggests that the disruption of animal farming by PFCA could begin far earlier than RethinkX’s original forecast, which found that the dairy industry could collapse by 2030.

In energy, AI’s ability to make predictions from large, complex datasets, as well as to automate tasks, can allow energy consumption and demand to be managed seamlessly. AI can help forecast the variable power generation and net load for renewable energy systems with far greater accuracy and efficiency, which in turn can reduce operational costs and curtailment of excess electricity.

In the new clean electricity ecosystem powered chiefly by solar, wind and batteries, plummeting AI costs will drive down wider operational costs of managing complex flows of energy between generating capacity, storage and consumers – as well as between numerous interconnected local, national and international electricity grids. A range of studies now shows that with optimal designs, solar, wind and battery systems can generate at least three times as much energy as today, at five to ten times cheaper with up to 90% less storage requirements.

AI is also poised to disrupt the materials sector especially in terms of manufacturing, including inventory and supply-chain management, along with predictive maintenance and production. In the emerging field of ‘materials informatics’ AI is applied to materials science discovery and development to analyse complex data on materials that can accelerate time to market and exponentially reduce costs of experimental design from “millions of candidates and/or thousands of experiments to more manageable hundreds, or even tens, of solutions or iterations”. There’s also the prospect of convergence with other disruptions such as 3D printing, where AI can potentially optimise and automate key processes resulting in order of magnitude cost reductions and reducing reliance on repetitive, manual tasks. AI will further accelerate cost reductions in industrial robotics and automation. ARK Invest anticipates that industrial robot costs will drop by 50-60% by 2025.

The doorway to economic abundance?

The advent of fully autonomous vehicles will involve a major leap in the capabilities of AI to model the physical environment from vast volumes of sensory data and then navigate that environment by interacting purposefully with it. According to my former colleague Adam Dorr, director of research at RethinkX, as AI can usually be rapidly adapted to new tasks across different sectors, the application of AV technology beyond simply self-driving to many new tasks will likely trigger a cascading avalanche of second and third order AI disruptions that will expand the scope of the AV technology ecosystem into vast new arenas of physical labour. In other words, the AV disruption – which is on track for the early 2030s – will be the main precipitator of the great automation disruption which we can then reasonably expect to follow shortly after.

This suggests that as early as the late 2030s, we can expect automation to begin rapidly disrupting jobs involving physical manual labour.

However, it’s not clear whether AI will necessarily disrupt other forms of employment involving cognitive tasks and creativity. There simply isn’t sufficient data to form hard conclusions. Some studies suggest that cognitive AI will augment skilled workers such as software developers rather than simply wiping them out entirely. The historical reduction of manual labour (largely agricultural in nature) did not permanently eliminate employment but instead transformed it, with industrial education systems playing a crucial role in moving people into new emerging industries requiring fundamentally new skills.

The first empirical study of the economic impact of generative AI on a real company has also brought counterintuitive results, finding that AI boosted the productivity of lower-skilled and novice workers, while having minimal impact on experienced and highly-skilled workers. It also appeared to reduce managerial interventions and improved employee retention. There is also now an emerging body of data suggesting that within the next two decades, AI may begin to eliminate manual labour while reducing the repetitive drudgery of manual dimensions of cognitive and creative work.

This poses both a tremendous risk and an unprecedented opportunity. The risk of course has been stated numerous times – that technological unemployment could lead to widespread societal disruption and social unrest. Yet it could also have another counterintuitive effect.

Economists widely recognise that labour costs are one of the main limiting factors in economic productivity. The capacity of technological improvement to drive down labour costs has been a major factor in increasing economic productivity. Yet since the 2008 global financial crash, there has been a prolonged slowdown in labour productivity growth. This has coincided with a long-term “phase of diminishing returns” in the global economy since the 1970s in the form of declines in the rate of GDP growth, energy return on investment (how much energy is put in compared to what we get out) and manufacturing productivity.

These diminishing returns are related fundamentally to the slowdown and demise of the incumbent industrial technological paradigm. However, as we’ve seen, disruptions across energy, transport, food, information and materials are rapidly overturning that paradigm and leading to the emergence of a completely new production system whose costs and ecological footprint are far lower and smaller.

By massively eliminating labour costs, the AI automation disruption in coming decades will dramatically diminish one of the most critical limiting factors in economic productivity. With the vast bulk of manual work becoming automated, AI will in effect eliminate this limiting factor and open the door to vast economic prosperity on a virtually inconceivable scale.

However, like all the disruptions taking place right now, the AI automation disruption cannot be managed within the centralised and hierarchical structures of the global political economy as we know it. Viewed through the lens of the incumbency, the AI disruption would empower existing centralised unequal structures of power while creating a vast new global underclass. It is difficult to imagine how such a dystopian scenario could be sustained without leading to societal regression and collapse due to conflict and economic dislocation. Within this lens, ‘band aid’ solutions such as a universal basic income (UBI) appear to make sense as a way to organise the trickle-down distribution of resources so that amidst vast wealth disparities sufficient wealth is allocated to the new global underclass to manage their existence and avoid a global uprising.

The only truly viable scenario involves a total rethinking of the global organising system. In such an economy characterised not by the scarcity that defines capitalism in its current form, but by a newfound abundance within planetary boundaries, we will need to fundamentally rethink and redefine the very nature of economic activity. The AI automation disruption will for the first time in human history create the possibility of a world in which manual repetitive labour is no longer needed to survive, largely extinguishing the biggest limit to economic prosperity and thus opening the door to unprecedented economic abundance. This will be compounded by the production system transformation which will also blur boundaries between capital and labour, by making individuals, households and businesses owners and producers of energy, food, information and transport.

However, to make this possibility of abundance a reality will involve a fundamental shift in how the global economy is organised. To a significant extent, the optimal design of the key technologies in the new production system will push toward such a shift from centralised control to distributed networks. Societal choices will need to move toward social, political, economic and cultural systems that are capable of harnessing and mobilising the new system.

In this new world, there will be entirely new possibilities to allocate and distribute wealth which transcend the wage-labour system of current capitalism. And in such a world without the need for manual labour, there will instead be new scope and freedom to expand the field of human creativity. Such possibilities include a vastly increased scope to explore scientific and creative pursuits, the arts, leisure and ultimately the meaning of human existence.

Yet all this will require new human-centric and earth-centric value systems, governance structures and economic protocols to maximise and distribute the benefits of the new system. Above all, then, the AI disruption will need to unfold within emerging frameworks for collective intelligence which are grounded in shared values based on recognising these positive possibilities and intentionally moving toward them.

In other words, the global phase-shift entails that whether we like or not, we are rapidly leaving behind the industrial system, and moving into a new system which could, with the right choices, create unprecedented possibilities for prosperity and abundance in a way that were previously unimaginable.

Yet as the global phase-shift accelerates, the demise of the old system and the speed of change is generating uncertainty and dislocation which could spiral out of control. The AI disruption represents a vast expansion of the informational capabilities of human civilisation which could propel humanity to new heights.

But if it unfolds without evolving the wider outmoded social, political, economic and cultural systems of the dying industrial order, instead of a transformation we will get an amplification of the most regressive features of these systems. This would represent a regression of civilisation into barbarism; at worst it would spiral into breakdown and collapse.

To get to a truly new system, to get through this ‘scale threshold’, we need to remake our wider organising systems. If we do that, we would be able to use today’s technology disruptions to solve some of our greatest challenges: we could forge the foundations of an advanced, ecological civilisation that empowers the human species and all life to flourish on a regenerating planet.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In