A Nasa space scientist, water management engineer and AI chatbot programmer walk into a bar. It sounds like the beginning of a terribly bizarre joke, but what if I told you that the work these three individuals do might be inextricably interconnected?

Everyday is juxtaposed with alarming events which seem completely disconnected. But understanding them through a new lens – the idea of a ‘global phase-shift’ – helps us to make sense of them as different signals of the same fundamental process.

Last year, NASA scientists released a speculative paper trying to explain why we have not yet been able to find any evidence of extra-terrestrial civilisations. They came up with the ‘Great Filter’ hypothesis – the idea that if other civilisations did evolve elsewhere in the universe, they wiped themselves out before they could communicate with each other, hence explaining why we can't find that evidence. Humanity, then, could be facing this same predicament from a convergence of different threats, from climate change to AI.

There can be little doubt that we are moving closer to a precipice – or that it very much feels like that’s what’s happening.

For the first time in human history, according to recent headlines, human activities have breached the planetary boundaries for water. That was the grim verdict declared at a science briefing to the United Nations General Assembly at UN Headquarters in New York in February.

In fact, the research behind this had come out last year based on finding significant reductions in soil moisture levels around the world, resulting in abnormally wet and dry soils – with huge implications for the Amazon rainforest, farmlands and the tropics.

This year has simultaneously seen a dramatic upsurge in artificial intelligence applications, with extensive focus on the rise of Chat GTP and its sometimes human-like conversations resulting in extremely strange and unexpected interactions involving threats, disobedience, and declarations of love. Some experts see the exponential rise of AI as an existential threat – believing that artificial general intelligence (AGI), a type of superintelligence that can programme itself, could become so powerful it endangers human existence due to being uncontrollable.

If AGI really is an ‘existential risk’, it’s hardly the only one on the horizon. As the global water crisis suggests, our current civilisational footprint is already eroding the planetary systems whose health is critical to our survival.

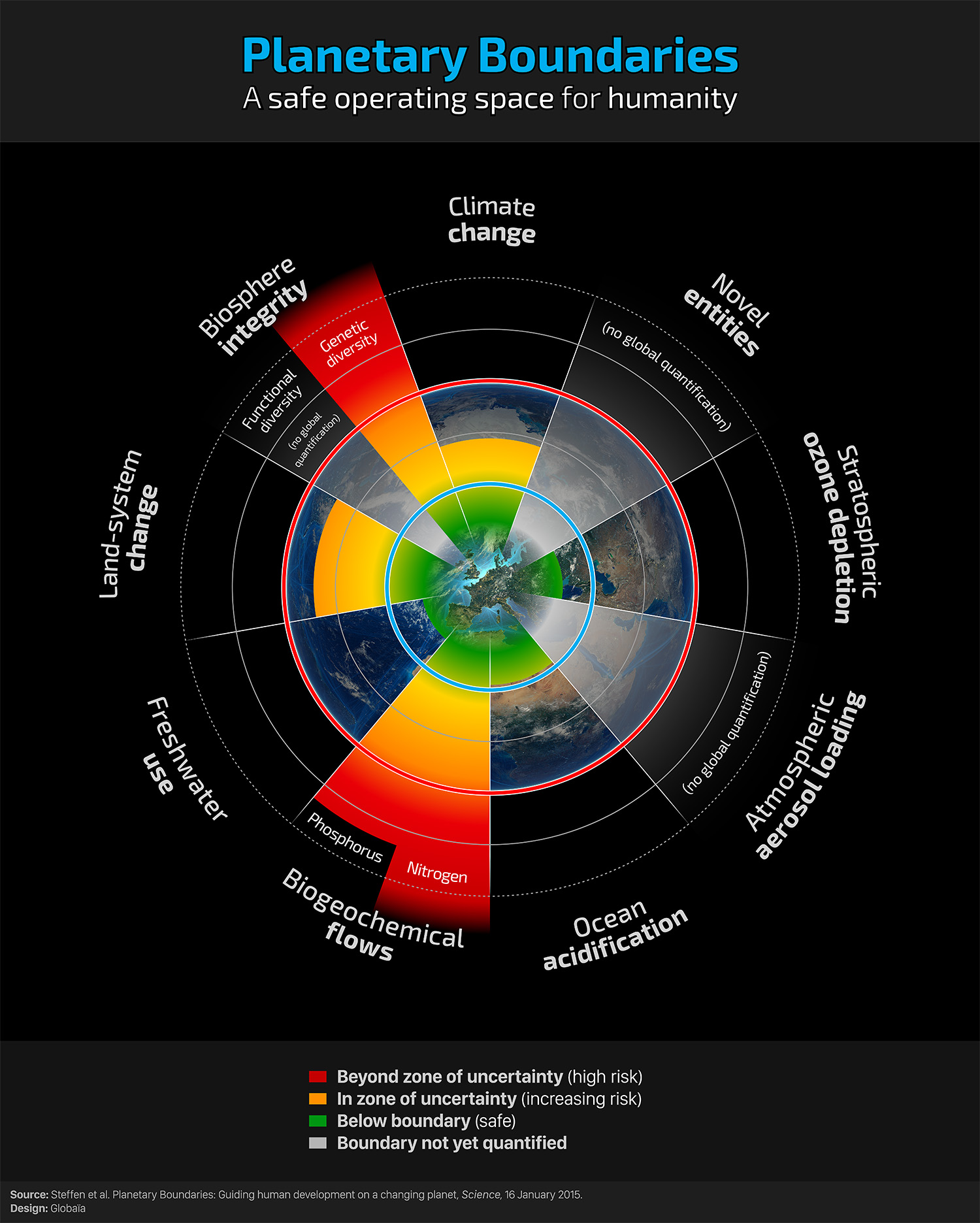

The ‘planetary boundaries’ framework developed by the Stockholm Resilience Centre in 2009 identified nine key ecosystems across the earth on which the stability of natural life support systems depend. If those boundaries experience too much disruption from human activities, then the scope for all forms of life to survive and thrive, would be significantly reduced. Scientists call this the ‘safe operating space’ for humanity.

By 2015, the scientists who had developed this framework discovered that we were at risk of transgressing four of these boundaries. Since then, the total number of boundaries where we have breached ‘safe limits’ has increased to six.

Climate change is only one of these boundaries. The others include ocean acidification, the ozone layer, forest degradation, agrochemical pollution, biodiversity loss, air pollution and toxic waste.

In short, we are disrupting the natural equilibrium of earth systems that has allowed human life to thrive over the last hundred thousand years or so - potentially permanently.

A Time of Fundamental Change

Why are these things happening at the same time?

What do they mean?

The synergy in these negative global trends can feel overwhelming and paralysing. It has pushed many of us into despair. Some of us look around and cannot see hope for the future given the destruction being wrought on the planet.

Yet this is because we are focusing on the inevitable death of the old, rather than the birth of the new that this entails. So let me start with the main concept, which will help us understand these developments in a new light.

Six years ago, I wrote a book called Failing States, Collapsing Systems: Biophysical Triggers of Political Violence, which you can read here for free. This was the first time I articulated the concept of the ‘global phase-shift’, which I set out as follows:

The cases examined here thus point to a global process of civilizational transition. As a complex adaptive system, human civilization in the twenty-first century finds itself at the early stages of a systemic phase-shift which is already manifesting in local sub-system failures in every major region of the periphery of the global system... In this context, it is precisely the acceleration of global system failure that paves the way for the possibility of fundamental systemic transformation, and the emergence of a new phase-shift in the global system… Human civilization is in the midst of a global transition to a completely new system which is being forged from the ashes of the old. Yet the contours of this new system remain very much subject to our choices today…. there remains a capacity for agents within the global system to generate adaptive responses that, through the power of transnational information flows, hold the potential to enhance collective consciousness. The very breakdown of the prevailing system heralds the potential for long-term post-breakdown systemic transformation.

This idea of a global phase-shift builds on a staple concept in some of our core natural sciences which we use to make sense of the dynamics of change: the 'phase-transition'.

What the hell is a phase-transition?

The idea of ‘phase-transitions’ comes from the extensive study of physical and biological systems and how they change. A ‘phase-transition’ occurs when a system undergoes a fundamental change of state, due to a “sharp transition” in the degree of organisation within the system as a result of changing external conditions or pressures.

At the small scale of physical and biological systems, the parameters that scientists use to understand what ‘phase’ a system is in – the level of organisation it exhibits – involves physical forces ranging from temperature to magnetism.

On the scale of human civilisation of course, understanding the parameters of global change requires a much wider systemic lens that brings together lots of different systems and their relevant properties.

We need to understand holistically not only what’s happening to the earth system but what’s happening within the human system on a planetary scale, and how these fit together all at the same time.

That’s where applying the scientific concept of ‘phase-transitions’ to our global predicament becomes really interesting.

Because if a giant whole-system ‘phase-transition’ is in fact happening on a global scale right now – which we can conceptualise as a global phase-shift – then we should be able to recognise it by checking some specific questions:

Is every major system that defines our current civilisational ‘phase’ in a state of flux?

Can we see signs of both breakdown, and breakthrough?

Do we see evidence that the rules and norms that define existing systems as we know them are changing rapidly?

Is this process contained to just a few systems, or is it happening across every system that might be seen as fundamental to the current global order?

My view is that the answers to all these questions is an emphatic yes.

The planetary boundaries framework, for instance, helps us see that every area of our relationship with key ecosystems in the earth system is not only in flux, but experiencing major disruption pushing the earth system toward a new state – one that, if it continues in this direction – could lead to a world that is largely uninhabitable.

Yet simultaneously, all our human systems are also in flux. When we take a birds-eye view, we can see, similarly, that our human systems are simultaneously moving into a new state.

What those earth system and human system states will ultimately look like remains undetermined. In the midst of phase-transitions, the breakdown and loss of the incumbent order creates a chaotic and destabilising uncertainty which, however, entails completely new openings by which to determine the structure of the next phase.

This is a time, in other words, where much that we took for granted is falling away; while the opportunities to rebuild anew are unprecedented.

The Human System

Defining our human systems is a highly contested if not fraught process, but systems sciences suggest that the most fruitful ways to do so are not reductionist, but holistic.

The human system, like the earth system, is made-up of multiple tightly-coupled sub-systems which, however, are deeply interconnected, if not inherently intertwined.

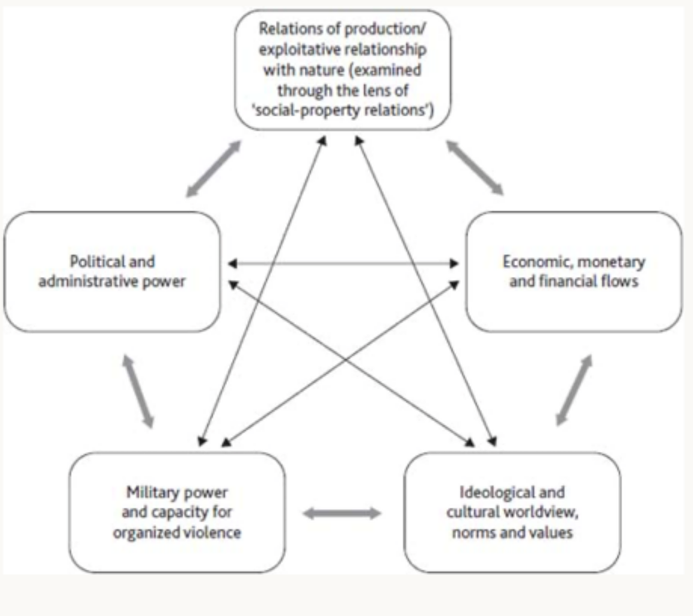

We have systems of production which encompass how we extract from nature to produce the things we need; these are configured by economic relations of social-property or ownership which determine how and who owns, controls, accesses, uses and distributes these resources; we have our economic systems by which we regulate our systems of production and consumption while allocating value to what we’re producing and how it’s consumed; we have our cultural and ideological systems which reflect how we see and understand the world, our place in it, and what things mean to us; we have our legal and political systems which regulate these structures.

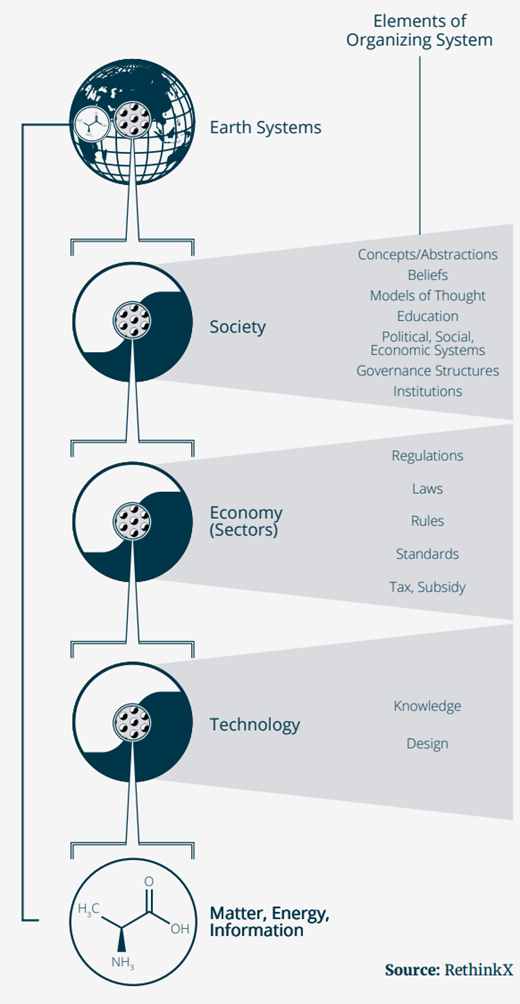

While all this seems like a lot to analyse, one framework which made a significant advance in making sense of how these different systems fit together came in the book Rethinking Humanity by James Arbib and Tony Seba, co-founders of RethinkX, a technology forecasting think-tank.

Although there are some significant theoretical and empirical limitations to Arbib and Seba’s framework, it broke new ground in developing a robust (though by no means exhaustive) theory of how to understand human systems.

Arbib and Seba essentially divide the human system into two broad sub-systems: the technological infrastructure of production which includes all the different sub-systems we use to produce the things we need – energy, transport, food, information and materials (the Production System). And the organisational infrastructure of other key sub-systems including society, culture, ideas, values and governance encompassing how a civilisation manages this technological infrastructure (the Organising System).

At the core of these systems, of course, is the energy system, which is the basis of how we are able to power everything we do across all our systems. However, as I set out in A User’s Guide to the Crisis of Civilization: And How to Save It, these systems are symbiotically interconnected in such a way that changes in one system entail changes across all the other systems. So the way we harness energy is intimately and mutually entwined with how we see the world, how we regulate our politics, and how our economy works – and vice versa.

Similarly, Arbib and Seba argue convincingly that the history and fate of human civilisation is not determined solely by one or the other major sub-system (the Production System or the Organising System), but by how they interact.

In fact, while they demonstrate that technological breakthroughs have always played a crucial role in pushing civilisations forward, they go to pains to make clear that the most crucial determining factor in whether a civilisation is able to survive and thrive depends on whether it evolves an ‘Organising System’ that is can manage the new tools it uses to produce what it needs.

With this somewhat refined understanding of the complexity of our human systems, we can see anew the extent to which all these key human systems are each moving through a ‘phase-transition’.

Everything is in phase-transition

The ‘phase’ or organisation of a system can be understood by inferring the ‘rules’ and ‘properties’ that define its behaviour. When a system moves through a phase-transition, these rules and properties are transformed as a new level of order emerges with completely new rules and properties.

Production system

While I was at RethinkX, I played a lead role in a number of projects scoping out how some of our foundational production systems are right now in the throes of transformation.

We showed with solid empirical data that three of the most carbon intensive systems of production – energy, transport and food – are in flux as incumbent industries are being disrupted and displaced by new emerging technologies which are scaling exponentially. In Rethinking Climate Change, we showed that these emerging technologies will scale rapidly within the next two decades. If deployed properly, they could help us not only reduce carbon emissions to zero, but to begin rapidly drawing down carbon from the atmosphere.

In other words, each of these foundational defining sectors of the production system of industrial civilisation is right now in the midst of a ‘phase-transition’ at the same time – which suggests that an entirely new production system is emerging, one that, with the right choices, could end up being ten times cheaper than the incumbent industrial system.

The hallmarks of this emerging production system are very different to what we’ve seen before. The new, exponential technologies are inherently decentralised and distributed, and they work best in the context of participatory structures and collective intelligence, in networks rather than centralised hierarchies.

Organising system

Separately, and as I pointed out in my first post, there is compelling evidence of a fundamental shift in human culture taking place on a global scale.

This global cultural shift encompasses widespread attitudes to our relationship with the environment, and to each other.

On environmental issues, one survey showed that 85% of people across 24 countries are willing to take personal action to protect the environment and live more sustainably. In the US alone, 65% of Americans polled believe that environmental protection should take precedence over economic growth, compared to just 30% who prioritised the economy over the environment (the widest margin since 2000). Another similar survey showed that Europeans consider climate change the single most serious challenge facing the world. It is the next generations who are leading the way for this emerging value-shift, with 90% of them seeing environmental problems as the top threat, and 77% recognising that there needs to be a change in consumption habits to preserve the environment.

On issues around governance, a poll of 19 countries across 5 continents found majority support for increased multilateral cooperation, and even for the major multilateral institutions like the UN, wanting them to take a lead on big issues like human rights, terrorism and climate change. According to the World Values Survey, there has been an unmistakeable increase in global support for gender equality. The WVS describes this as “part of a broader cultural change that is transforming industrialised societies with mass demands for increasingly democratic institutions.” And while there is still a majority view that men are better political leaders than women, “this view is fading in advanced industrialised societies, and also among young people in less prosperous countries”.

Of course, these are not the only indicators. Numerous other polls and surveys confirm that we are simultaneously witnessing increasing rates of social polarisation: declines in trust for democratic institutions, growing distrust of different political and ethnic groups, growing divides between men and women, increasing loneliness, increasing mental health challenges, and many other negative trends.

In other words, the core cultural components of our global human system are in phase-transition even as other major components of that system – such as the economy and politics – are also experiencing phase-transition breakdowns.

So while we are on the one hand witnessing the emergence of shared values on a scale we’ve never seen before in history, we’re simultaneously seeing regressive cultural, economic and political forces which threaten to tear us apart. So yes, culture wars.

But of course what's most fascinating are the demographic contours of the so-called culture wars: the more nationalist exclusionary trends are largely associated with older populations associated with the old, dying industrial paradigm. The more pluralist, inclusive and ecologically conscious trends are being spearheaded by younger generations, those who are going to inherit the earth... so, as I said, this is a very real shift pointing to the fraught but inexorable emergence of a new global culture.

The Great Metamorphosis

What does this all mean?

It means that the human project as a whole is experiencing a great metamorphosis. The collapse of the old paradigm is symptomatic of the demise of the old rules and norms, as it makes way for the emergence of new systems.

The implications are stunning. The entire human system is in a state of flux, driven by multiple simultaneous phase-transitions across all the major sub-systems that define its production and organising systems. The idea of a ‘global phase-shift’ captures this underlying, all-encompassing process of fundamental change.

The next decade, perhaps two decades, will be the most disruptive and consequential in human history. This is not just a ‘transition’, but a complete transformation. Human civilisation is experiencing a Great Metamorphosis in which our energy, politics, economics, culture, values and worldviews are being rewritten, and we are the authors, but we haven’t quite realised this yet.

The demise of the old system with which we are so familiar naturally feels frightening.

But the newfound openings for outsize impacts can feel exhilerating. We are experiencing, for instance:

- An acceleration of seemingly disparate events, and an amplification of their impact.

- An increasing probability of 'Black Swann' events which appear to be intrinsically impossible to predict.

- An increasing complexity of events involving multiple systems and factors tending to converge across silos and sectors.

- The slowing down and obsolesence of legacy systems and worldviews in understanding and responding to the speed and interconnection of change.

- Chaotic and polarising information flows tending toward silo-ed, reductive approaches; as well as new shoots of more coherent information flows tending toward more holistic, integral and transcendent approaches.

Looking at events with the recognition that they are fractal episodes within the global phase-shift can help us open our eyes to what’s urgently needed from us in these momentous times.

We need to do everything we can to accelerate the emergence of the new system, which entails both rapid technological deployment and comprehensive rewiring of our social, organisational and value systems.

And we simultaneously need to do everything we can to mitigate the negative impacts of the unravelling of the old system, all the while harnessing the best of human sciences, arts and cultures to build bridges from here, to there.

We all have different roles to play in the global phase-shift. Some of us will be focusing on material innovations; some of will be looking into social issues; some of us will be exploring breakthroughs in consciousness studies.

Whatever role we decide to play, our choices will be pivotal. As the NASA-funded study I mentioned at the beginning of this piece points out, the precondition for our civilisation surviving is “collaboration” as a species. To create a “robust and permanent society”, the study concludes, “both the individual and the institution must bring about awareness, and in turn, reform to higher ideals”.

This is, in other words, an evolutionary moment.

Despite what the headlines scream, what politicians are doing, what powerful lobbies are scheming, despite all of that, amidst of all of that, our job is to empower and accelerate the most positive material and cultural shifts unfolding before our eyes and within our communities. These material and cultural shifts are already here – they are blossoming up inexorably all over the world, demonstrating the indefatiguable beauty and resilience of the human spirit, against even the most terrifying odds.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In