This special report was commissioned by the Hub Foundation, courtesy of Zachary Markwith.

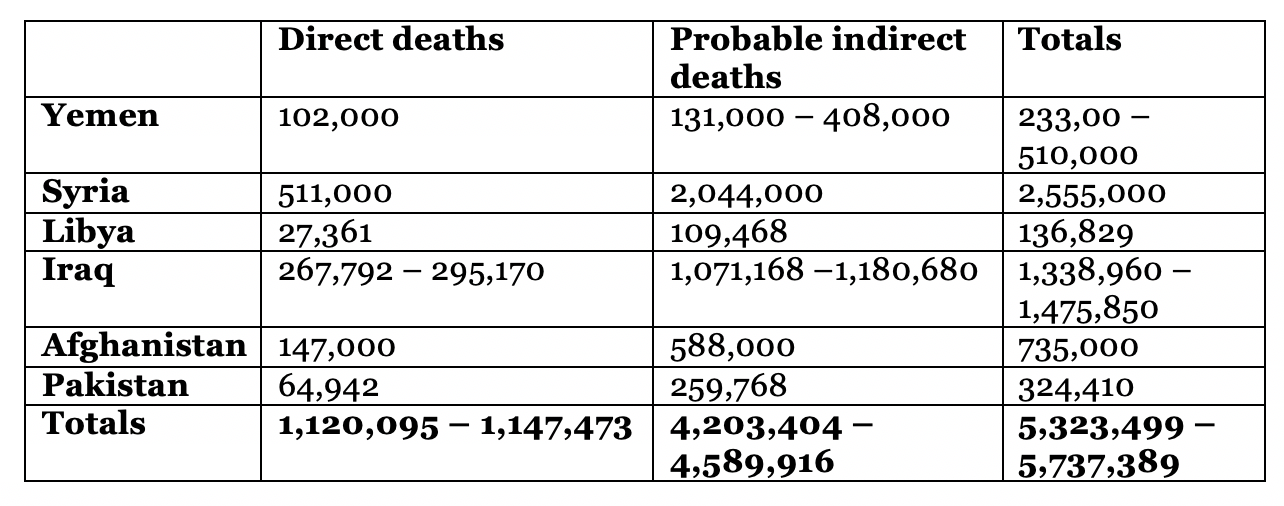

The last two decades have seen an astonishing escalation in mass violence against Muslims across vastly separated geographies. While its true impact remains officially unknown, collating data across multiple studies suggests that at least 1 million and as many as 6 million Muslims may have been directly and indirectly killed since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, through a sequence of inter-state wars, civil conflicts, and military interventions involving major powers, as well as Muslim and non-Muslim regimes.

Although death toll figures are often hotly contested due to their moral and political implications, even the most conservative figures demonstrate a colossal scale of deaths, raising urgent questions about the legitimacy of Western and non-Western militarism.

The escalation suggests that this uptick in mass violence in different parts of the world, many instances of which are genocidal in character, is not an unhappy coincidence but rather a product of a wider pattern of relationships integral to the way the modern world system has developed.

War in Yemen: a genocidal campaign

One new study published earlier this year pinpoints the genocidal nature of the US-UK backed Saudi war on Yemen. Authored by genocide scholar Professor Jeffrey Bachman of the School of International Service at the American University in Washington DC, the paper examines the scale, pattern and intentionality of the coalition bombing campaign across Yemen.

“Coalition aerial attacks have intentionally targeted Yemen’s civilian infrastructure, economic infrastructure, medical facilities and cultural heritage,” Bachman observes. “Combined with the ongoing air and naval blockade, which has impeded the ability of Yemenis to access clean water, food, fuel and health services, the violence visited upon Yemen has created near-famine conditions.”

Meanwhile UNICEF has predicted an imminent cholera outbreak which could infect more than one million children. Drawing on the work of the conceptual founder of genocide, Raphael Lemkin, Bachman develops a holistic conception recognising that the existence of a group can be attacked through multiple, overlapping techniques across political, social, cultural, economic, biological, physical, religious and moral domains.

Applying this approach to the war on Yemen, Bachman argues that the coalition is “conducting an ongoing campaign of genocide by a ‘synchronised attack’ on all aspects of life in Yemen, one that is only possible with the complicity of the United States and United Kingdom.”

Anglo-American complicity in this “campaign of genocide” boils down to the fact that the US and UK governments “have provided the Coalition with aid and assistance that is essential to its ability to commit its attacks and maintain the blockade, the results of which, together, constitute genocide.”

Bachman is a professorial lecturer in human rights and the director of ethics, peace and global affairs at American University’s School of International Service. He is the author of Cultural Genocide: Law, Politics and Global Manifestations, just published last June as part of the Routledge Studies in Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity series.

In his Yemen paper, Bachman argues that it is immaterial whether the US and UK themselves intend for this support to go towards committing genocide by destroying a group in whole or in part. Complicity exists as long as their support is intended to facilitate the coalition’s military campaign, especially given that both governments are fully aware of the foreseeable genocidal consequences in terms of the mass destruction of all aspects of life in Yemen.

The key to Bachman’s argument is in how he situates the role of intentionality in relation to the actual consequences of the war, which has systematically targeted all critical infrastructure underpinning the existence of Yemen as a functioning society. The mass deaths of Yemenis and the collapse of Yemen society and life is an inevitable result of this.

Whether or not the US and Britain explicitly intended this outcome, by supporting the coalition despite the clear evidence that this is the foreseeable outcome, they are complicit through their implicit intent in the partial destruction of Yemenis as a group.

Deaths in Yemen

Like most modern wars, the death toll in Yemen is as yet not fully known, and potentially unknowable. As has become the norm, no government wants to keep track of the body count.

But according to a UN-commissioned report by the University of Denver, the total number of people killed in the war on Yemen by the end of 2019 is about 102,000 people.

This does not account for the number of ‘indirect deaths’ occurring as a result of the consequences of the war. The report further estimates that some 131,000 Yemenis by this date will die from hunger, disease and lack of health clinics and other infrastructure caused by the conflict. Between 2015 and 2019, then, some 233,000 Yemenis will have died due to the war.

That study was recently corroborated by data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project, which similarly estimated that the direct death toll is already approaching the 100,000 mark.

But this could still severely underestimate the extent of the deaths.

According to the Secretariat of the Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence, an authoritative diplomatic initiative endorsed by over 90 states, indirect deaths usually vastly outnumber direct deaths. The patterns in which this take place suggest an average ratio of indirect to direct deaths in modern wars which we can use to infer some likely estimates of probable indirect deaths, acknowledging of course that these estimates will be subject to a large margin of error.

“In the majority of conflicts since the early 1990s for which good data is available, the burden of indirect deaths was between three and 15 times the number of direct deaths,” the initiative found.

The variation in the ratio of direct to indirect deaths, the initiative explains, depends on several factors including the pre-conflict level of development of the country, the duration of the fighting, the intensity of combat, access to basic care and services, and humanitarian relief efforts. Data on conflicts preceding the publication of the initiative’s report, however, suggested a narrower – but conservative — average range:

“A reasonable average estimate would be a ratio of four indirect deaths to one direct death in contemporary conflicts.”

The initiative thus uses this baseline calculus from the ratio of direct to indirect deaths in past conflict data to provide a conservative ratio by which to reasonably estimate the likely burden of indirect deaths from armed conflict, in new cases where we can discern similar levels of comprehensive destruction of the critical infrastructure necessary to sustain normal civilian life.

This ratio is, of course, not a fool-proof approach to calculating indirect death tolls, but does provide an evidence-based method to generate plausible estimates.

In the Geneva Declaration Secretariat’s own words, this method can be used to generate an “order of magnitude” for indirect deaths from armed conflict which is likely to be conservative. We apply the same methodology below.

Applying it in the case of Yemen, where critical public health infrastructure has collapsed due to the bombing campaign, would suggest it is reasonable to suspect that the scale of indirect deaths in Yemen is much higher than the 233,000 estimate — and could be as high as around 400,000 (and probably much higher).

This would put the probable total death toll in Yemen including direct and indirect deaths at around half a million people.

Genocidal violence in Syria

Bachman is also the author of an earlier major genocide study focusing on reconceptualising the nature and impact of the US government’s relationships with genocidal regimes — The United States and Genocide: (Re)Defining the Relationship, published by Routledge.

His book makes clear that the sociological conception of genocide applied to the Yemen case points to the tendentially genocidal dynamics of numerous other conflicts in which Western governments have been complicit.

In this respect, Yemen is only among the latest in a long sequence of regional conflicts that have erupted in recent years, following on from what was arguably the first major disruptive regional event, the 2003 Iraq War. This triggered a domino effect culminating in the outbreak of a series of interconnected wars across the Middle East and North Africa.

The parallel conflict that erupted in 2011 and which continues to this day is in Syria. It is widely recognized that the Syria death toll is extremely difficult to pin down due to the complexity of tallying numbers with reports of deaths, coming in from areas where incidents of violence cannot be independently verified by foreign observers.

However, one of the most authoritative estimates of the war — which cannot be dismissed on grounds of partisanship — came from the Damascus-based Syrian Centre for Policy Research (SCPR), a nonpartisan think-tank which held good relations with Assad’s government.

In 2016, the SCPR estimated that 11.5 percent of the Syrian population had been either killed or injured, with nearly half a million people — some 470,000 — having been killed directly or indirectly as a consequence of the war. This total is nearly double the UN figures of 250,000 deaths, which the UN stopped collecting 18 months earlier.

The SCPR’s estimate seems to be broadly corroborated by the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), which puts the direct death toll at 511,000 as of March 2019. SOHR’s data on fatalities comes largely from volunteers based in opposition-held territories. While SOHR’s data has been questioned on partisan grounds, the convergence between the SCPR and SOHR estimates indicates that the half million figure is very likely to be an accurate baseline estimate, with the actual death toll probably higher. Independent statisticians have also cross-referenced SOHR with other databases of casualty figures.

If the direct death toll figure of around 500,000 is accurate, then applying the Geneva Declaration ratio would suggest a total of 2 million indirect deaths in Syria from the war, providing a total death toll of around 2.5 million.

Lines of complicity in the Syria conflict can be seen encompassing both Western and non-Western powers. In my own major investigations into conflict narratives in Syria, while the complicity of Assad, backed by Russia and Iran, in carpet bombing civilians indiscriminately is absolutely unmistakeable, so too is the role of Western powers in intervening in the conflict in ways which have entrenched and exacerbated the violence — including the US military’s own indiscriminate aerial bombing of civilian areas.

There are two lines of critique in this respect which are worth noting, and they are not necessarily contradictory.

One is that the West’s approach to the conflict fanned the flames in such a way that it emboldened Assad in his efforts to crackdown on opposition forces and civilians. Another is that through the Gulf states and Turkey, the West armed and financed largely extremist groups among the opposition forces which tended to weaken the most democratic and secular centres of these movements, while empowering hardline jihadist groups, many with connections to al-Qaeda and ISIS.

It could be argued that these two dynamics foreseeably reinforced each other in unleashing outbursts of violence and counter violence from different sides which, by deliberately targeting critical civilian infrastructure, were genocidal in their implicit intent to destroy at least in part target groups.

In fact, two US military documents — one an internal planning assessment and another a public analytical report — suggest that some US policy-planners were neither truly committed to toppling Assad, nor wanted to guarantee a rebel victory for fear of lack of control of the final outcome. The documents indicate that US strategy instead was to continually hedge its bets during the conflict with a view to fracture Syria’s territorial integrity and weaken its existence as a cohesive state.

Those documents should not be generalized to assume that this was always a fixed policy of Western governments wholesale, but they are certainly indicative of the type of covert counter-democratic strategic intentionality active at certain times, and underscore how the West — alongside other powers — contributed to the genocidal destruction of Syrian society in different ways.

NATO’s genocidal military intervention in Libya

Just as unrest was breaking out in Syria, conflict was also breaking out in Libya, eventually prompting NATO intervention to topple Colonel Qaddafi.

A study in the Journal of African Medicine concluded that a total of 21,490 people had been killed in the armed conflict between 2011 and 2012.

Other agencies have documented war deaths from later episodes of violence. Libya Body Count, which tallies deaths described in media reports, counted a total of 5,871 deaths from 2014 to 2016 due to the outbreak of another civil war.

Conservatively, then, we are looking at a death toll of around 27,361 up to 2016, which by now has probably neared 30,000. But keeping with the figures which we can consider to be reasonably confirmed, applying the Geneva Declaration ratio would suggest that indirect deaths from the war in Libya likely amount to about 109,468 people. Total direct and indirect deaths from the war in Libya, then, are likely to approximate 140,000 people.

Like the US-UK backed Saudi air campaign in Yemen, NATO’s bombardment of Libya also exhibited genocidal characteristics when we apply the holistic conception developed by Professor Bachman.

In a report for The Ecologist, I documented evidence that NATO had deliberately targeted Libya’s critical water infrastructure with the foreseeable consequence of sparking a massive humanitarian emergency that could turn into an unprecedented public health epidemic. In particular, NATO’s destruction of water installations had made it impossible to sustain the functioning of the state-owned Great Manmade River (GMR) project, which supplied water to some 70 percent of the population. At the time, the GMR’s disruption left 4 million people without potable water. Libya’s national water crisis continues to this day.

This devastating outcome was anticipated. Private intelligence firm Stratfor even predicted that the disruption would lead Libya’s population, which had doubled since 1991 thanks to the GMR, to collapse “back to normal carrying capacities” — a clear indication of the foreseeable nature of this genocidal outcome vis-à-vis population collapse, and the tendentially genocidal intent implicit in the conduct of NATO’s war.

Post-9/11 genocidal wars

The eruption of this sequence of regional conflicts from Libya, to Yemen, to Syria followed directly from the destabilization of the region that had begun with the 2003 Iraq War.

We now know that the West’s intervention fueled the sectarian conflict in Iraq, emboldening Iran’s encroachment into the country and pitting many Shi‘ah against an increasingly radicalized Sunni insurgency, parts of which drew in and joined forces with al-Qaeda. This, in turn, provided the cauldron of violent radicalization from which emerged the so-called ‘Islamic State’ (ISIS), and a legion of other Islamist militant factions which began to accelerate their operations across Libya, Yemen and Syria.

The 2003 Iraq War had, of course, proceeded in parallel with the invasion of Afghanistan, both of which were justified as the pivotal mechanisms of military response to the 9/11 attacks.

In November 2018, Professor Neta C. Crawford, Co-Director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University, published a paper tallying the total direct death toll from post-9/11 wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The paper found that 147,000 people were directly killed in Afghanistan, 64,942 in Pakistan and between 267,792 and 295,170 in Iraq.

The total amounts to between 479,743 and 507,000 people directly killed in the main post-9/11 Western military interventions — a monumental scale of death which massively outweighs the violence of the terrorist attacks which served to justify these wars in the first place.

As these were only fatalities occurring as a direct result of the war, indirect deaths due to the consequences from degradation of civilian infrastructure will have been far higher. Using the Geneva Declaration standard to estimate concomitant indirect deaths from these conflicts suggests a total of between 1.9 and 2.1 million people dying from the consequences of these wars since 9/11. When added to the direct death total, this suggests an overall total of around 2.4 to 2.6 million total deaths.

At first glance these colossal figures might seem extraordinarily high, but this scale has been corroborated by other studies. In 2015, I reported on the findings of a landmark study by the Washington DC-based Physicians for Social Responsibility (PRS), concluding that the death toll from 10 years of the ‘war on terror’ since the 9/11 attacks is at least 1.3 million, and could be as high as 2 million.

The 97-page report by the Nobel Peace Prize-winning doctors’ group was authored by an interdisciplinary team of leading public health experts, including Dr. Robert Gould, director of health professional outreach and education at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, and Professor Tim Takaro of the Faculty of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University.

The PSR study found serious methodological flaws and omissions in a number of previous estimates of ‘war on terror’ casualties. It dismissed the figure produced by the NGO Iraq Body Count (IBC) of 110,000 dead, derived from collating media reports of civilian killings, as necessarily too low due to its dependence on media reporting which would tend to undercount incidents.

The problem with this approach, the PSR study noted, is that such ‘passive’ reporting methods invariably and inevitably undercount the total number of actual deaths, simply because media reporting tends to miss large volumes of deaths especially due to limitations on reporting in fraught conflict zones. Such methods also inherently ignore indirect deaths produced as a consequence of war.

Apart from identifying various gaps in the IBC’s database, the study also critically examined other studies on the Iraq War death toll. The review found that a much-disputed Lancet study which estimated 655,000 Iraqi excess deaths up to 2006 (and over a million until today by extrapolation) was likely to be the most accurate. That study applied the statistical methodology that is the universally recognised standard to determine both direct and indirect deaths from conflict zones, used by international agencies and governments.

When factoring in the death tolls in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the PSR’s total estimate of deaths was between 1.3 and over 2 million, which coheres with the probable estimates suggested above.

Politicization of the body count

At the time of publication, the PSR study was attacked by a number of researchers associated with the IBC project. The debate that ensued prompted me to conduct a series of further investigations into IBC’s methodologies, including the work of one of the most prominent IBC associates, Professor Michael Spagat — who had published a widely-cited and highly influential series of academic papers critiquing excess mortality estimates of the Iraq War death toll, especially the Lancet study. Spagat’s thesis was that the Lancet authors had produced a fraudulent study that breached basic scientific standards.

My investigation, to which Spagat offered no response, found that Spagat himself had committed a range of serious methodological errors of his own in his critique of the Lancet study. His errors were so egregious and so systematic, that they revealed to the contrary that it was Spagat, not the Lancet authors, who had put forward a number of fraudulent arguments which breached scientific standards.

Despite some legitimate reservations, my critique was taken seriously by a number of statistical authorities including the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG), who had previously assumed that Spagat’s arguments on Iraq were correct. My investigation also confirmed that both Spagat and IBC more broadly suffered from deep conflicts of interests due to working with and directly accepting funding from Western governments and agencies who had been supportive of the Iraq War, and which had a vested interest in minimizing the scale of death in that war, and Western wars generally.

Spagat for instance has consulted for NATO in the creation of the so-called Dirty War Index, a ‘passive surveillance’ death toll counting methodology which systematically undercounts civilian deaths, overcounts other kinds of deaths, and generates serious inaccuracies; similarly, his work undercounting the Iraq War death toll has been cited with open arms by senior Pentagon officials attempting to sanitize US military responsibility for violence, despite his methods being critiqued by HRDAG.

The extent of complicity

It is not entirely surprising that some social scientists are actively being coopted by Western government agencies to promote models which underplay the violent impact of Western wars.

In all these conflicts, Western states have been directly complicit through various mechanisms of geopolitical interference, proxy warfare, aerial bombardment, and sponsorship of parties engaged in violence.

But it is important to note that complicity does not solely belong to Western states. Complicity also involves, often principally, multiple non-Western states engaged in exacerbating mass violence, including major rival powers like Russia, as well as Muslim regimes such as the Gulf states, Iran and Turkey.

Equally, this often does not obviate Western complicity in genocidal violence against Muslim groups. Complicity frequently extends to cases where Western powers may not be directly involved, but are nevertheless engaged in other mechanisms of indirect support. In these cases, the prime perpetrators are non-Western states, but a combination of Western silence and behind-the-scenes support illustrates varying degrees of complicity.

Large swathes of Asia, for instance, have become subject to pandemics of anti-Muslim violence and ethnic cleansing campaigns, bearing alarming genocidal features, and where Western governments have operated close alliances with the perpetrator regimes.

In India, incidents of communal violence targeted against Muslims have risen 28 percent between 2014 and 2017. The escalation of violence has occurred with the complicity of Indian law enforcement, egged on by political leaders affiliated with the ruling BJP party, which has openly castigated Muslim identity. According to news data portal India Spend, 97 percent of reported hate attacks in the name of the cow since 2010 occurred after President Modi was elected in 2014. About half the attacks were on Muslims, while 86 percentof the people killed were Muslims.

Despite this violence, India has strong relations with major powers, including the West which is keen to capitalize on what is presently the world’s fastest growing economy.

In Myanmar, armed forces, police and paramilitary forces have since 2017 forcibly expelled over 730,000 Rohingya Muslims who are now residing as refugees in countries like Bangladesh, India and elsewhere. A total of nearly one million reside in refugee camps from previous episodes of violence. Some 5–600,000 Rohingya in Rakhine state, the locus of the violence, face dire conditions and live under constant threat. UN investigators have concluded that the violence amounts to ethnic cleansing and genocide, and leaked Myanmar government documents reveal official plans for the “mass annihilation” of the Rohingya.

But Western governments, despite prolific condemnations, have been complicit in the genocidal violence by maintaining strong trade, business and in some cases military relations with the Myanmar regime.

It is not just Western governments that have turned a blind eye to the destruction of the Rohingya people, but also Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and Qatar. All of them want to benefit from Myanmar’s ethnic cleansing of the Rakhine state for a major pipeline route. US, British, Australian and European oil majors, for instance, have been awarded contracts by the Myanmar government, including BG Group and Ophir (UK); Shell (UK-Netherlands); Statoil (Norway); Chevron and Conoco Phillips (US); Woodside (Australia); Eni (Italy) and Total (France).

Many of these contracts — particularly those involving Chevron, Ophir, Woodside, and Eni — are production-sharing initiatives in the Rakhine basin, just off the coast from where the genocidal violence is accelerating.

Meanwhile in China, an estimated over one million Uighur Muslims are being forcibly detained in ‘re-education’ camps in the Xinjiang region, without due process, on the basis of countering extremism.

Credible reports have emerged based on firsthand eyewitness accounts of torture, ill-treatment, and forced political indoctrination at these facilities, where children are often routinely separated from their parents. Peter Apps, director of the Project for the Study of the 21st Century, describes the incarceration as “almost certainly the largest mass incarceration of a racial or religious group since the Holocaust” which, however, is “neither front-page news nor a major part of diplomatic or political dialogue”.

In fact, both Western governments and major companies, including Silicon Valley giants like IBM, have played a direct role in helping to build China’s giant surveillance regime in Xinjiang currently being deployed largely against Uighur Muslims. Western complicity also extends to the eagerness of governments and businesses to invest in China despite its responsibility for this genocidal campaign.

Rushan Abbas, founder and director of the Campaign for Uighurs, whose own family has been abducted by Chinese authorities as retaliation for speaking out, calls the anti-Uighur policy a case of “slow motion genocide”.

The genocidal character of the policy is evident in its attempt to extinguish the Uighur’s existence as a distinctive social, cultural and religious group through systematic targeting, forcible incarceration and mass indoctrination designed to eliminate their cultural and religious identity.

Between Myanmar and China, a total of at least 2.5 million Muslims have been ethnically cleansed and imprisoned in detention camps.

The coming tipping point

The total number of Muslims who have died since 9/11 in wars for which Western states bear significant culpability is truly staggering. Unfortunately, while we can be reasonably certain of the direct death toll, the scale of indirect deaths remains unknown and we are forced to rely on probable estimates. These estimates are not suggested here as final, but rather as tentative, yet still plausible (and very likely highly conservative), figures which further urgent excess mortality research might be able to firm up.

At a minimum, focusing purely on the minimum conservative figures based on direct deaths, around which there can be little room for doubt, we have an alarming direct death toll of around 1.2 million Muslims from post-9/11 conflicts in which Western powers along with Muslim regimes, terrorist groups and rival non-Western powers are complicit.

However, these figures are not only likely to be a severe undercount on their own terms of the actual direct death toll; due to reliance on methods which tend to produce more conservative estimates, they do not account for the volume of deaths that will have been produced as an indirect consequence of wars due to the destruction of health, water and other critical infrastructure, and the impact of direct war casualties on societal functions; they also exclude certain conflicts, focusing on some more well-known conflicts (I acknowledge that to some extent the reasons for this focus may be arbitrary). When factoring in likely indirect deaths and applying the Geneva Declaration’s baseline ratio, probable total indirect deaths due to post-9/11 wars can be estimated at between 4.2 and 4.6 million deaths.

This implies that total direct and indirect deaths of Muslims across these six theatres of war amounts to between 5.3 and 5.7 million people. The full statistical range suggests that at least 1.2 million and more likely just under 6 million Muslims have died in the sequence of regional conflicts since 9/11. Once again, this analysis cannot provide precision, but gives a conservative sense of the likely order of magnitude.

Beyond that, a further 2.5 million Muslims face genocidal ethnic cleansing campaigns in Myanmar, from which they have been forcibly expelled, and in China, where they are being imprisoned in brutal detention camps the likes of which have not been seen since the Second World War.

Simultaneously, across the heartlands of the Western world, Islamophobic sentiment is at record levels, with Muslim communities facing epidemics of hate crimes, institutional racism, and legislative discrimination. As far-right populist parties have grown exponentially in popularity across the US, UK and Europe, as well as parts of Latin America and South Asia, they have increasingly normalized and mainstreamed hostility toward minorities along ethnic, religious and sexual lines, and to perceived ‘foreigners’, particularly migrants and asylum seekers.

The global convergence and acceleration of these trends in violence indicates that while they are being whipped up in the context of local and national factors, they are nevertheless intensifying as part of wider world system dynamics which are little understood. This is a global system that is increasingly tending to produce episodes of escalating genocidal violence in more and more regions of the world. While Muslims are currently a chief target, other minorities including Jews, black people, and LGBTQ+ people are also increasingly at risk, and being targeted in different ways.

These trends represent a continuation in new forms of the kinds of discriminatory political violence that prevailed during the colonial era. Perhaps the most worrying issue is that despite their gravity, this scale of violence is largely unknown and features little in public consciousness or policy debate.

This analysis also illustrates that the dynamics of genocidal violence have transformed after the Second World War.

Rather than being necessarily concentrated in the bureaucratic forces of a single centralized state, they are dispersed among multiple states and across multiple regions; yet despite unfolding over vastly different geographical territories, they carry common genocidal characteristics which have resulted in similar consequences: the death, persecution and incarceration of millions of people, and the increasing political tendency resulting in the social construction of those people as members of a homogenous group whose existence is seen as obstructive to various geopolitical goals, and therefore morally and functionally expendable.

As the forms and dynamics of genocide have transformed, then, arguably so too has the nature of fascism, which though believed to have been defeated over 70 years ago, in reality has quietly metamorphosed, subsisting implicitly and manifesting through outbursts of state repression via the postwar structures of Western liberal democracies, while resurfacing overtly in authoritarian societies like China, Myanmar, Russia and the Gulf states.

In itself, the relative blindness to the systematic escalation of these trends of political violence in particular, as far-right ideology and politics is resurgent, suggests we could be approaching a dangerous tipping point in mass violence of which minorities, and particularly Muslims, are at grave risk.

A new analysis of one of the largest databases of world conflicts lead authored by Dr Gianluca Martelloni of the University of Florence, covering the last 600 years, identifies patterns in the outbreak of major episodes of mass violence. The data examined in this working paper shows that wars have become less frequent but more destructive over time, with far greater fatalities in modern times. Although large wars are less probable than small ones, they tend to be triggered in the context of smaller conflicts through a process of escalation. The data also indicates that we could be statistically overdue for a particularly large episode of global mass violence.

Co-author of the paper, Professor Ugo Bardi, a systems theorist and earth scientist also at the University of Florence, argues that “statistically, a new pulse of exterminations could start at any moment and, the more time passes, the more likely it is that it will start. Indeed, if we study even just a little the events that led to the 20th century democide that we call the Second World War, you can see that we are moving exactly along the same lines.”

The rising trends of racism, fascism, sectarianism, ethnic cleansing and inequalities, he argues, “can be seen as the precursor for a new, large war engagement to come.” In particular, he points to the arc of mass violence that “starts in North Africa and continues along the Middle East, all the way to Afghanistan and which may soon extend to Korea. We can’t say if these relatively limited democides will coalesce into a much larger one, but they may become the trigger that generates a new gigantic pulse of mass exterminations.”

Action

Given that those “relatively limited democides” comprise a continuum of escalating genocidal mass violence — having already killed at least a million people and potentially as many as nearly 6 million (based on a conservative methodology) — there are strong grounds for concern over how these trends might escalate in coming years.

The remaining question is how to forestall or prevent such an escalation.

For Muslims, my recommendation is to undertake and act on spiritual reflection from within the Islamic tradition. One particular prediction of the Prophet Muhammad is worth noting. He reportedly said, according to an authenticated narration (Imam Dani, Al-Sunan al-Waridah fi’l-Fitan, Hadith №3260):

“When people will break their promises, God will place over them their enemy (as a ruler); when they will fail to enjoin good and forbid evil (amr bi’l-ma’ruf wa nahy an al-munkar) then God will place over them the worst of people; then the best amongst you will pray but their prayers will not be answered.”

The key to understanding this tradition is in the meaning of the concepts of enjoining ‘good’ and forbidding ‘evil’.

The Qur’an’s use of the terms ma‘ruf (good) and munkar (evil) implies a far broader meaning than is often assumed. Ma‘ruf and munkar convey a sense of ethical values which are universally recognized and understood. Ma‘rufmeans literally ‘that which is commonly known or accepted to be right’, while munkar means ‘that which is universally rejected as wrong.’

In more contemporary but still accurate terms, ma’ruf signifies “the public good.” According to Muhammad Khalid Masud, Director General of the Islamic Research Institute at the International Islamic University in Islamabad, the term ma‘ruf signifies “right” or “rights” that are “well known and familiar… in the sense that it is through social discourse that it becomes well known. People agree to its being right on the basis of a consensus that develops by a process of mass communication, debate and social understanding.”

The powerful insight from this, then, is that according to the Prophet’s warning, a core driver of the extraordinary repression of Muslims across the world today is a fundamental spiritual malfunction — a failure to fulfil the core goal of upholding shared ethical values of love, compassion, generosity, justice and beyond (which are co-extensive with the Divine Names) universally recognized by humankind. This obligation is bound up with the Qur’anic stipulation that the very origination of human existence is by way of ‘trusteeship’ over the Earth on behalf of the Divine, with each human being playing the role of planetary caretaker for God.

This core insight suggests further that the pathway of action — to both challenge this genocidal system and transform it — requires Muslims and non-Muslims to work together to forge bonds of solidarity, which revolve around manifesting these core ethical values in efforts to transform repressive political and cultural structures as well as socio-economic systems.

That requires working to build new paradigms of nonviolent co-existence and cooperation which, instead of pitting human beings against each other and the planet, establish new bases to cultivate and recognize their inherent interconnections.

“God does not change the state of a people until they bring about change themselves.” (Quran 13:11)