The inflection point that our civilisation is experiencing today on a global scale is unprecedented, but it’s not unique.

Societies and civilisations have risen and fallen throughout history, and every civilisation goes through a life cycle of growth and decline.

One powerful attempt to examine the rise and fall of civilisations using complexity science was by Utah State University archaeologist Joseph Tainter, in his book, The Collapse of Complex Societies. Published in 1988 by Cambridge University Press, Professor Tainter examined two dozen cases of collapsed societies, including the fall of the Western Roman empire, Mayan civilisation, and Chaco civilisation. His far-reaching theory was that societies collapse when their investments in social complexity reach a point of diminishing marginal returns.

The pattern that Tainter found again and again was that civilisations would develop more complex and specialised bureaucracies to solve emerging problems. As this process continued, with each new layer of problem-solving infrastructure, a whole new order of problems would be created. Further infrastructure is then developed to solve those problems, and growth escalates.

As each new layer also requires a new ‘energy’ subsidy (greater consumption of resources), it eventually cannot produce enough resources to both sustain itself and resolve the problems generated. The result is that society collapses to a new equilibrium by shedding layers of complex infrastructure amassed in previous centuries. This descent can take place in a matter of decades, or last as long as centuries.

While this emerging science of civilisational collapse has become more prominent – agencies from NASA to the UK Foreign Office have commissioned research around these areas – it is only part of the picture: because ‘collapse’ has frequently been a precursor to civilisational renewal.

From collapse to renewal

Some scholars argue that oversimplistic renderings of the idea of collapse distract from an ongoing human capacity to keep going forward. They argue that ‘collapse’ might not always offer the right lens.

In 2005, the renowned American geographer Jared Diamond released his seminal Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive arguing that environmental change has played a key role in driving societies to experience “a drastic decrease in human population size and/or political/economic/social complexity, over a considerable area, for an extended period of time”.

Diamond's was not the last word on the subject, though.

Shortly after, a group of specialist historians looking at his work concluded that due to his Western-centric lens of ‘progress’, he had systematically overlooked evidence that many of the human societies he thought had failed were remarkably resilient.

In the book Questioning collapse: Human resilience, ecological vulnerability, and the aftermath of empire, edited by anthropologists Patricia A. McAnany and Norman Yoffee, the historians argue that rather than collapsing, these societies shifted, evolved and adapted in different ways that Diamond overlooked.

Northumbria University archaeologist Guy Middleton in his 2011 book Understanding Collapse: Ancient History and Modern Myths reaches a similar verdict. Reviewing all the best examples of societal collapse, he suggests that the evidence for total collapse in each case is limited: aspects of a given society might decline, certain buildings or settlements might be abandoned, and particular regimes or states might be overthrown, but this does not mean that a civilisation as a whole has collapsed. Often the collapse of specific political structures paved the way for transformation, albeit in new and unexpected ways that involved population continuity as well as increasing social complexity and economic prosperity.

In other words, the ‘collapse’ of these civilisations was not necessarily the ‘end’ of these societies and communities, and did not always result in the total disappearance of their culture or people. Instead, we find evidence that while prevailing political structures declined and disappeared, people continued to adapt, to shift, to reorganise.

On the other hand, it’s also clear that as the organising structures and capabilities of major civilisations did, indeed, disappear, sometimes their populations moved into new structures that emerged with new civilisations.

Building on this theme, earth system scientist Professor Ugo Bardi at the University of Florence – author of Before the Collapse: A Guide to the Other Side of Growth – found that while collapse is ubiquitous throughout history, it regularly paves the way for new forms of civilisation.

Examining a wide-range of collapse cases across human societies, in nature, and through artificial structures, he found that collapse is often the precondition for the emergence of new, evolutionary structures. He coins a term for this process – a ‘Seneca Rebound’ – finding that new societies which emerge after collapse often grow at a faster rate than what went before.

Bardi’s work is part of a wider body of evidence suggesting that the rise and fall of civilisations in history is part of a longer process of human cultural evolution. This research draws on the seminal work of the late ecologist Crawford Holling, who spent decades studying natural systems, from predator-prey dynamics to forests.

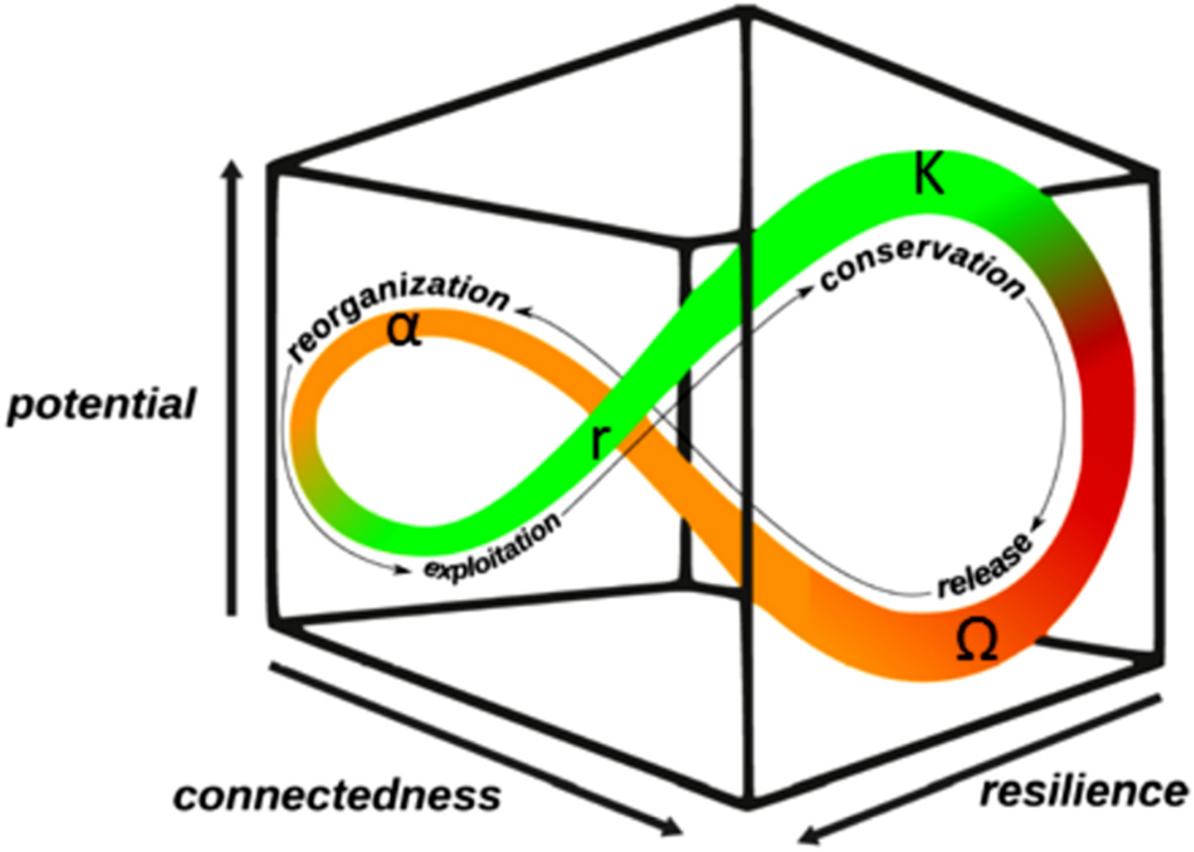

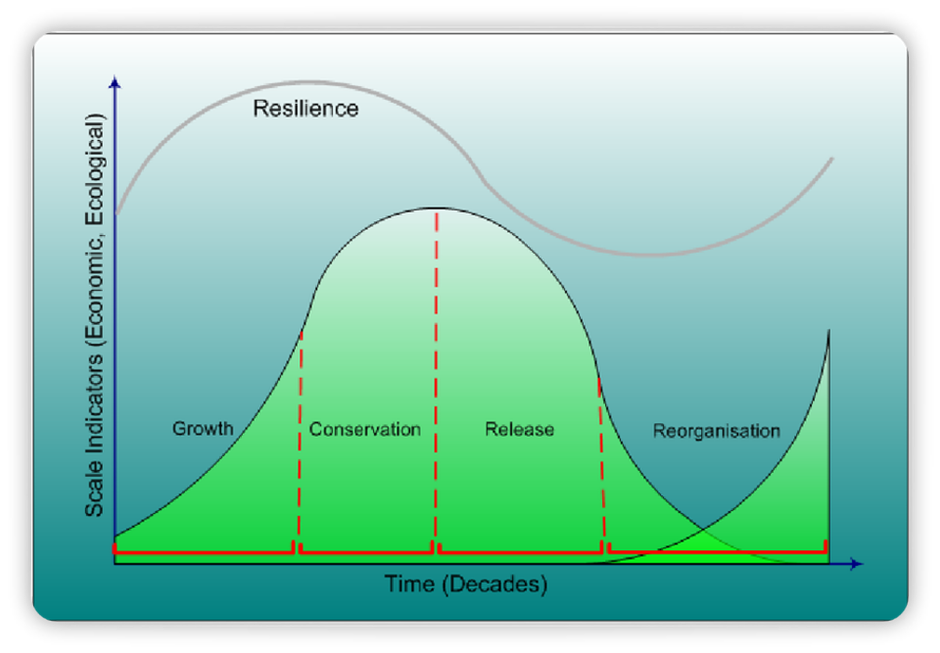

Holling found that all ecological systems experience a life cycle which goes through four stages: growth, conservation, release, and reorganisation. Holling called this the ‘adaptive cycle’.

Since then, scientists have found that the adaptive cycle is applicable to social systems and organisations, and can be used to understand processes of political change. As observed by Stewart Brand, the founding president of the Long Now Foundation, Holling’s framework can be used powerfully to make sense of the huge social-ecological system that is human civilisation.

The global phase-shift

Applying Holling’s framework to the history of industrial civilisation is massively insightful.

Using his categories, we can mark the first stage in the life-cycle of industrial civilisation as growth, which took place rapidly over perhaps 200 years or so from the nineteenth century until the late twentieth century. This growth was driven not only by the discovery of cheap, abundant energy from fossil fuels, but also a spiralling sequence of technological innovations, each of which created new systems and dynamics for society.

Through a long process of struggle and adaptation among different social groups, new cultural dynamics, property rights, civil rights, governance systems, norms and values co-evolved with the global production system that emerged in this period, to manage these new systems.

Civilisation then went through the second stage of conservation which stabilised between 1970 and the early 2000s. During this period, the global system consolidated itself, becoming extraordinarily strong and interconnected. This period coincides with the ‘golden age’ of neoliberal globalisation, during which a set of ideas and values about modernity and development were propagated around the world. Simultaneously, this very process reduced the resilience of the system as it became ‘self-adapted’, organised to keep sustaining itself. While seemingly more robust than ever, the system was in reality brittle and unable to respond to shocks that might change the conditions to which it had become adapted.

The third stage, the release phase, appears to have begun around 2005, escalating through 2010, to 2020 until today. This is a period of uncertainty and chaos as the system begins to decline.

Before we move onto the fourth stage, let me set out my thinking on the three fundamental reasons the release stage has kicked in:

- the defining technologies of industrial civilisation, by which we extract resources from the earth and use them in the economy and society, appear to have reached the internal limits of their own productivity;

- as part of those limits, they are generating escalating costs and diminishing returns from massive and intensifying social and ecological shocks that are symptomatic of their overextension;

- perhaps most importantly and frequently overlooked, they are being outcompeted by emerging technologies that are more efficient, cheaper, and higher performing.

On the one hand, the growing uncertainty as the old system declines unleashes a host of negative, polarising forces. The incumbent neoliberal paradigm that was once the overarching standard of success has lost its mass appeal. The grand narratives which once worked because they co-evolved to define the growth phase of industrial civilisation, work no longer. Prevailing ways of seeing the world, incumbent norms and values, are breaking down, fostering an alarming escalation of confusion, disagreement and conflict.

But something else also opens up in the release stage: within the widening cracks of the old, dying system, new spaces come into being. As the old system enters a downwards spiral, it weakens. And in that weakening, there is both polarising chaos and the opening up of new possibilities for change, where small perturbations in the system can have deep impacts in ways they could not do during the first and second phases.

This process then leads to the fourth and final stage, reorganisation, where the mobilisation of new possibilities gives rise to a new system within the ashes of the old. In this stage, the foundations of a new life cycle are planted. The space between the old and the new life cycles are a 'phase-shift' - a total reconfiguration, transforming from one system to another with different rules, properties and dynamics.

Applying this on a global scale to industrial civilisation, the first two decades of the twenty-first century appear to be part of what I’ve called a global phase-shift, a momentous transformation from one global system to a new global system triggered by the decline of the old system, and the potential birth of a new one.

There is also something novel about our current predicament that we’ve never seen before in history. For the first time, the global scale of the crises we face threatens to unravel civilisation as we know it, with the worst-case climate scenarios alone pointing to the risk of an uninhabitable planet this century (and that’s without thinking through the complex, cascading effects of intensifying combined energy, climate, food and economic crises).

On the other hand, we are for the first time able to see and understand these processes as they unfold in real-time. We can recognise the risks of decline and collapse in a way that no society in history has ever been able to do. Among these risks is the danger that as system decline accelerates, the possibility of breaking through to the next system, to a new life cycle, become constrained and shrunken by the chaotic, destructive impacts of the dying industrial paradigm.

The danger, in other words, is that human system destabilisation – which is precisely a symptom of this process of systemic decline – grows so out of control, that it derails the global phase-shift, and accelerates the process of decline to the point that the system crashes before a new one can be born.

Looking through the lens of the adaptive cycle reveals that perhaps the biggest danger of all is that we become so focused on these negative risks from accelerating into the current release phase, we fail to recognise the vast new opportunities for systemic reorganisation and rebirth.

Here, in the third phase of the life-cycle of our civilisation, the unravelling of prevailing norms, values and institutions is terrifying – but it is also the precursor for the emergence of the next life-cycle, an unprecedented opening for renewal and revitalisation. Within this radical uncertainty, the space for the truly new and ground-breaking is widening at breakneck speed.

The engine of rebirth

So we face a grand challenge: to scale this stage of release so that we can accelerate toward an effective reorganisation occurring in fourth phase of the life-cycle of our current civilisation, laying the foundation for a vibrant new civilisational life-cycle.

It is this which is the defining, pre-eminent mission of our times.

To succeed, we need to understand the drivers behind the mysterious ‘Seneca Rebound’ effect that earth scientist Ugo Bardi identified – where societal collapses often create clearing grounds in which new civilisations are born and flourish.

One of the most profound analyses of these drivers was published by the technology forecasting think-tank RethinkX in 2020. In their book Rethinking Humanity: Five Foundational Sector Disruptions, the Lifecycle of Civilisations, and the Coming Age of Freedom, James Arbib and Tony Seba showed how civilisations were propelled forward by a profound combination of two key things:

- technological leaps in their production system;

- cultural leaps in their collective social organising systems.

This research, in my view, helps us understand how Holling’s insights on the life-cycles of natural systems apply not only to human civilisation, but to our prospects today.

Arbib and Seba showed that a civilisation’s production system encompasses five foundational sectors: energy, transport, food, information and materials. All of humanity’s pivotal technological leaps can be found in any of these sectors. The invention of the wheel, for instance, revolutionised transport. The invention of writing was an information disruption. The domestication of plants in the food sector was instrumental in the shift from hunter-gatherer to agricultural societies.

Often, technology disruptions in one sector would have huge cascading effects across other sectors, driving innovations and transformation. But Arbib and Seba’s most compelling insight was that a civilisation’s ability to succeed was not just about improving its technological ability to produce the main things that people need.

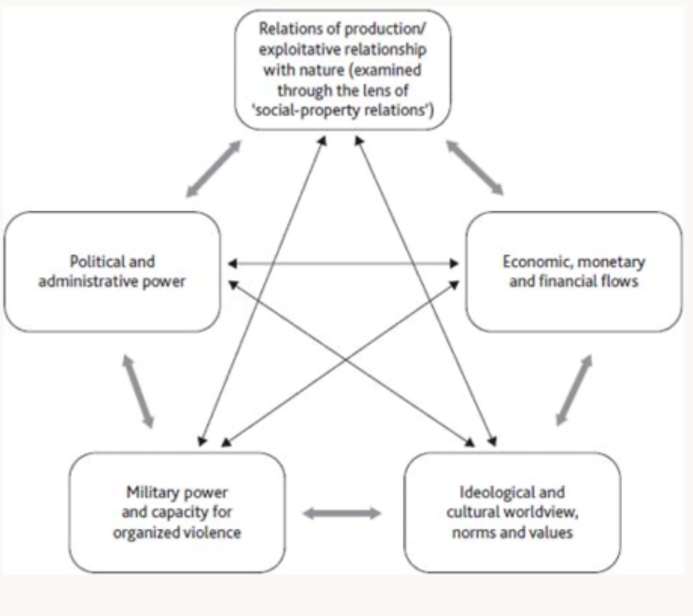

It was about its ability to harness and distribute the benefits from these key innovations in a way that strengthened its social and organisational capabilities: this is what Arbib and Seba call a society’s ‘organising system’, encompassing its worldview, social norms, value systems, governance structures, political institutions and so on.

Arbib and Seba pointed to a pattern of disruption which weaves through human history. Societies and civilisations were propelled forward by technology disruptions that improved their ability to produce things by extracting resources. But these disruptions were not simplistic ‘one-for-one’ substitutions of whatever tool or product that existed before: they created totally new ways of doings things that were, in essence, new systems with new rules, properties and dynamics. The car, for instance, wasn’t just a faster horse. It was a totally different beast which completely transformed our entire way of life, creating both new benefits, and new challenges.

So civilisations needed to co-evolve organising systems – rule sets, value sets, cultural norms and beyond – which were able to adapt to and harness these new systems. Sometimes, however, societies failed to do so. Stuck in the old system organising paradigms adapted to fit status quo production tools, they were unable to adapt to the dynamics of the new systems emerging, leading to chaos and decline.

Often, though, societies would collapse as the dynamics of extraction-age production tools led them into a cycle of diminishing returns. Civilisations would get locked into a feedback loop of extracting resources, expanding militaries, conquering land, and then needing to do more of the same as the massive bureaucracy required to maintain increased rates of extraction – now necessary to sustain the whole system – were even larger than before.

As business-as-usual generated escalating crises, plagues, famines and so on, the solution – continued expansion – ended invariably with overextension and collapse.

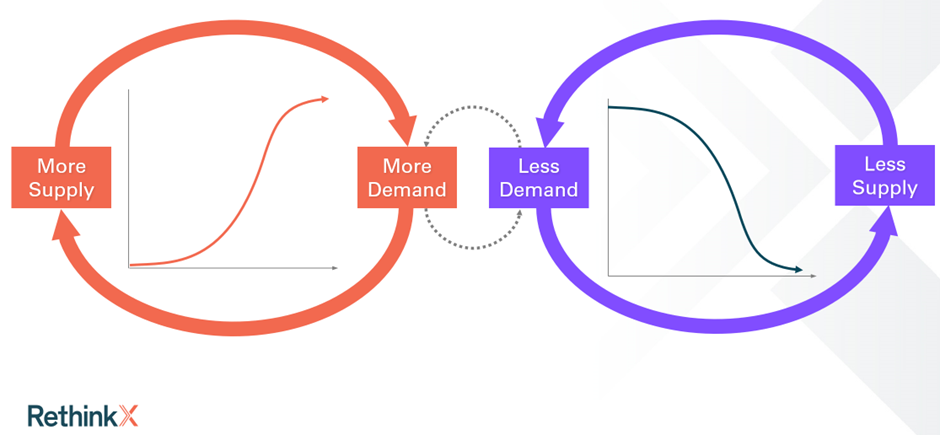

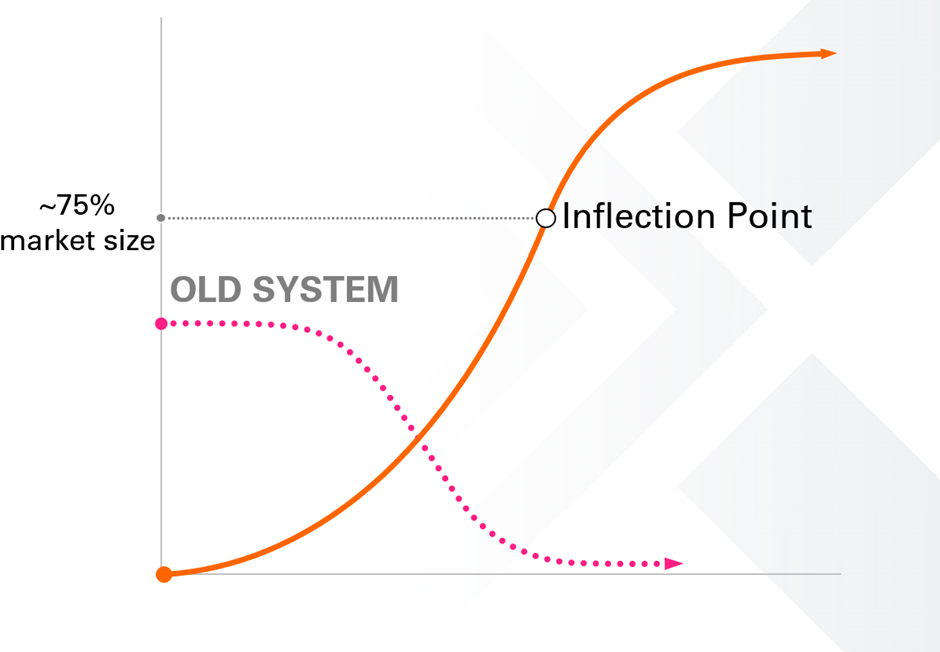

This pattern of rise and fall has been captured by Holling’s adaptive cycle. But both the front loops and back loops of Holling’s cycle bear astonishing resemblance to the S-curve pattern of technology disruptions, which Arbib and Seba find to be intimately related to a civilisation’s growth trajectory.

Technology disruptions throughout history have followed the same pattern. As Rethinking Humanity shows, drawing on Seba’s Technology Disruption Framework, they start slowly, based on innovations which build on, combining and reconfiguring, previous technologies in different sectors. If those innovations meet wider societal needs or demand more efficiently and effectively than incumbent tools, they get more widely adopted.

Technology disruptions tend to follow their own pattern of learning-by-doing. The more they are deployed, the cheaper they get. And when they are 10x cheaper than incumbent tools – today we measure this in money but we are really talking about them using a tenth of the energy or resources of prevailing technologies – they are economically unstoppable: it simply makes no sense to stick to the old tool. Swiftly, then, the disruptive technology scales up to mass adoption, levelling off as it becomes ubiquitous.

Waves of technology growth and decline follow the same pattern as Holling’s adaptive cycle. While the emerging technology experiences exponential improvements in cost, efficiency and performance, the incumbent technologies experience the opposite: escalating costs, declining efficiency, dwindling performance, which culminate in diminishing returns and deteriorating competitiveness.

This drives an incumbent technology into total obsolescence – collapse – a process that is visible in the downwards slope of release. Meanwhile, the disruptive technology, which is often based on a convergence of multiple pre-existing technologies across different sectors, takes off – driving a new life-cycle that is usually larger than the previous.

This parallels Ugo Bardi’s finding that the collapse of a civilisation often precedes an even faster and bigger growth spurt for a new civilisation.

Holling’s adaptive cycle throws light on how this trajectory plays out as it co-evolves with a society’s organising system. It follows an exponential growth trajectory which then levels off as the system reaches saturation. And it dips into decline when the system runs up against either internal limits, or faces competition from a new, superior system.

When the decline curve mapping the collapse of the old system is superimposed on the S-curve mapping the birth of the new system, it looks like an X.

Twilight of the age of extraction

Given that civilisations at their fundamental level can only come into being and expand based on these five dimensions of production – how they power themselves; move around; find, grow and distribute food; learn and exchange knowledge; as well as extract materials and make things – it is not surprising that the same S-curve and X-pattern that we see in technology disruptions is also visible in the life-cycles of societies and civilisations.

This insight has massive implications for the global phase-shift that we find ourselves in right now.

The incumbent industries that define our civilisation today are all in their twilight as they enter vicious cycles of accelerating decline involving escalating costs, diminishing returns, and slowing performance.

The climate and ecological emergency comprises one overarching symptom of this comprehensive decline across the major industries that define civilisation’s energy, transport, and food systems in particular. Fossil fuels, internal combustion engine vehicles, and conventional agriculture are together responsible for around 90% of carbon emissions.

As the climate crisis is intensifying, it is amplifying other crises – whether in geopolitics, economics, food and beyond – which in turn is increasing costs on the whole system, and undermining the capacity of these industries to continue operating profitably.

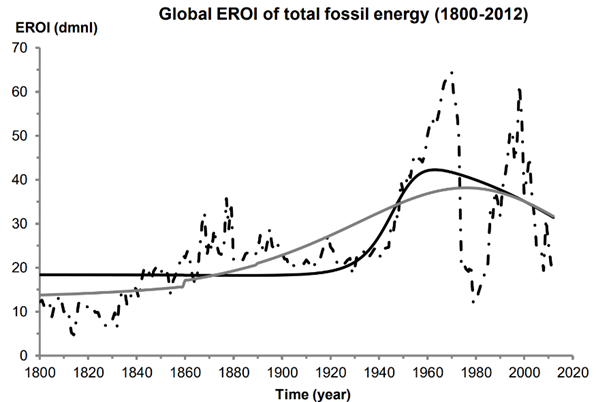

Simultaneously, these extractive industries are collapsing under their own weight as they hit up against both planetary boundaries and their own limits. One of the biggest signals of this is in the concept of Energy Return On Investment (EROI), pioneered by systems ecologist Professor Charles Hall of the State University of New York. EROI is a simple but powerful ratio that measures the amount of energy used to extract energy from any given resource.

Numerous studies have shown that the EROI of global fossil fuels peaked around the 1960s and is now in terminal decline.

A separate study led by French scientists found that at this rate, by 2050 fully half of the energy extracted from global oil reserves will need to be put back into new extraction to keep producing oil. This level of energy use just to get oil out is so huge it makes the whole enterprise pointless.

This precipitous decline is happening so fast that if we leave it too late to transform the global energy system, by the time we get round to doing so it might not be economical to extract the energy we need to sustain this very transformation.

The signals of collapse are not just blaring in climate and energy. They are perhaps loudest in the global food system, where recent studies have warned of the possibility that compounding problems – including escalating energy costs coupled, the impact of climate disasters, water scarcity due to global heating, as well as the impact of industrial techniques such as soil degradation – are together overwhelming the system’s capacity to continue growing food at the same rate.

According to Asaf Tzachor, a researcher at Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, the prevailing “global system of food and agriculture is constrained by finite resources, it is prone to operational instability, it fails to prevent famine and micronutrient deficiencies, and it is a prime contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, climate change and ecosystems collapse”. Business-as-usual, he warns, “may engender further global catastrophic risks (GCRs)”, because it operates in “self-undermining, self-debilitating dynamics, disrupting yields and supply chains”, which could trigger “GCRs”.

The spectre of collapse signals two things.

Firstly, the eruption of identity politics and culture wars, the resurgence of far-right, Islamist and other forms of extremism, the escalation of geopolitical destabilisation and so on are all symptoms of the decline of civilisation’s organising system: the prevailing order, worldview, value-set and mindset are becoming increasingly obsolete because they simply cannot understand reality and solve our problems.

And secondly, that process is inherently connected to the technological decline of the prevailing fossil fuel-dominated production system, where escalating costs and diminishing returns are derailing the foundations of how our societies create the things we need.

All these negative signals are only one side of the release phase – the dark side. There is a light side that is intimately bound up with these processes: the rapid transformation of every foundational sector that defines civilisation.

Across energy, transport, food, information and materials, a series of eight technologies are becoming more powerful, ubiquitous and cheaper than incumbent industries. Together they are providing us unprecedented capabilities to transform our civilisation and solve our biggest global challenges including climate change – providing we work together to make the right choices.

But the unfolding technological leap is only half of the equation. Technologies are, ultimately, reflections of our overall relationship with the natural world - how we extract from nature. They are inseparable, then, from economic, political and social structures.

Robust data suggests that the entire production system of our civilisation is in the process of transformation; that the industries at the pinnacle of the age of extraction are collapsing; and that industries heralding a new age of creation are emerging, bearing the seeds of the next life-cycle of human civilisation.

But these new technologies are emerging within the bowels of the old, centralised, hierarchical industrial organising system. To scale the global phase-shift, we need to not only accelerate unfolding technological disruptions happening today in the best ways; we must take a cultural leap that permits us to harness them for the largest benefit to people and planet.

To ride this wave, we need to rethink everything: rewire the very sinews of how our civilisation operates from the ground up, and reassess who we really are at the deepest levels.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In