Official documents and reports reveal that some of the West’s biggest technology giants — from IBM to Microsoft — helped Huawei build the Chinese surveillance regime being weaponised against the Uighur minority. Now an Austrian firm, Frequentis, is using Huawei technology to supply ‘public security agencies’ in Britain, Europe and beyond. Boris Johnson’s love affair with the Chinese tech giant is only the latest episode. In this exclusive story, we reveal not only how Huawei played an integral role in the emergence of China’s repressive domestic security apparatus used today to round-up the Uighur minority, but how US, British and European companies have aided and abetted the rise of Huawei with no regard for the horrifying consequences.

To the chagrin of the Donald Trump administration, Boris Johnson’s government is allowing Huawei to help build Britain’s 5G network — except its more “security critical” components including anything related to military and nuclear installations. But Huawei technology has already penetrated deep into British and European security communications infrastructure. And the Trump-Johnson tension over Huawei overlooks the fact that companies from the US, Britain and Europe have played a key role in helping the company develop the world’s largest authoritarian surveillance project in China’s Xinjiang region.

China’s ‘smart city’ complex currently tracks some 2.5 million residents across Xinjiang, specifically targeting the province’s Uighur Muslim minority. If a person is flagged for suspicious activities — such as praying — they could be investigated by Chinese intelligence, and detained in ‘re-education’ camps designed to strip them of any semblance of ‘Muslim’ identity.

Currently, at least one million ethnic Uighur Muslims have been interned since 2017 in what amounts to the largest mass incarceration of an ethnic or religious group since the Holocaust. In August 2018, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination offered an estimate of up to 2 million Muslims, including other minorities such as Kazakhs and Uzbeks, detained in these camps. Survivors and eyewitnesses describe horrific experiences of torture, rape and abuse.

Across the 500 or so suspected detention camps dotted throughout Xinjiang, new research published in BMC Medical Ethics suggests that every year since these camps were set-up, some 90,000 Uighur Muslims are executed to harvest and sell their live organs and body parts. The implication is that in addition to millions being detained, hundreds of thousands have been killed.

A new study in the journal Laws by Ciara Finnegan of the National University of Ireland’s Department of Law concludes that this evidence points to a pattern of “cultural genocide” by Chinese authorities, designed to erase the existence of the Uighur minority as an independent cultural identity. Other experts agree.

According to Dr Joanne Smith Finley, Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies at Newcastle University’s School of Modern Languages, China is reconstructing “the Uighur body, mind, language, religion and culture as an existential and biological threat to the Chinese nation” — in effect, a form of “genocide as social control. She describes the ‘re-education’ programme as “a ‘final solution’ to defeat a perceived anti-colonialist movement and erase the Uyghur identity as that movement’s lifeforce.”

The intrusive surveillance apparatus that operates across the Xinjiang province, allowing authorities to identify Uighur suspects for detention, was created in large part by Huawei. Yet Huawei did not achieve this feat by itself: it do so with a little, well actually a lot, of help from its Western friends.

One of these friends is the iconic American technology giant IBM, which has grown increasingly close to Donald Trump in recent years.

IBM: Planting the seeds

Trump has railed against Huawei as a threat to US, British and European national security, and condemned Britain for jumping into bed with Chinese tech giant.

Yet he has said nothing about IBM’s integral role in bankrolling Huawei’s rapid expansion.

In 2019, the CEO of IBM, Ginni Romety, joined Trump’s American Workforce Policy Advisory Board. In January 2020, she joined forces with Ivanka Trump to launch a national campaign for jobs. This is reflective of IBM’s close relationship with the White House across party political lines. Overall since 2008, IBM has received $1.7 billion in contracts from Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) alone. Under Trump, in particular, IBM became the biggest supplier of government tech.

The same firm designed the blueprint for China’s surveillance apparatus, under what it beguilingly called a ‘Smarter Planet’ concept for more efficient, sustainable cities. It sounded amazing on paper. But it turned into a dystopian nightmare.

IBM first seeded its ‘Smarter Planet’ concept in China in 2009, convening 22 forums across the country to engage with over 200 city mayors. That year, IBM established a joint ‘Eco-City’ research lab with Northeastern University in Shenyang City, funded with RMB275 million from the local government. The project aimed to develop new products that could later be sold to other local Chinese governments covering carbon emission reductions, energy conservation, water management, as well as enhancing the intelligence of transport and traffic systems.

In 2010, IBM announced a 10-year smart city development strategy for China at a conference in Beijing, based on refining intelligence from mass data intelligent solutions to transportation, food safety, manufacturing, water resources management, energy and public services. IBM then went on to sign a range of strategic cooperation agreements with numerous Chinese cities to develop their ‘smart’ capabilities.

Among IBM’s first projects was a ‘cloud’ solution in Chengdu encompassing food safety, education and telecommunications, in particular developing a major pilot with China Mobile to establish a city-wide wireless network that would facilitate urban management.

So far, so benign. Yet while the stated goal of these projects was improving public welfare, from the very beginning the design of IBM’s technological solutions for China opened the door to comprehensive forms of surveillance.

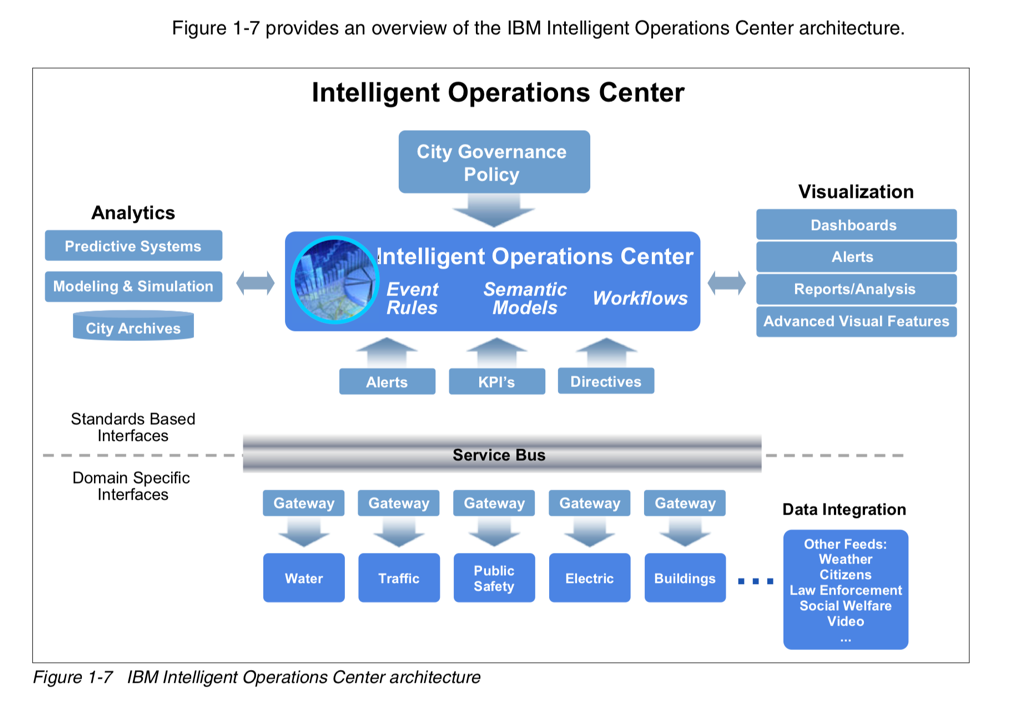

Among its early smart city projects was one in the city of Zhenjiang in 2012, where IBM installed its flagship Intelligent Operations Center (IOC) for Smarter Solutions to act as “the central point of command for the city.” Although the project focused on enhancing the public transport and bus scheduling system — by using sensors that would allow real-time monitoring of traffic, buses and passenger behaviour — IBM’s IOC was explicitly designed to integrate data in a way conducive to surveillance by government agencies for ‘security’ purposes.

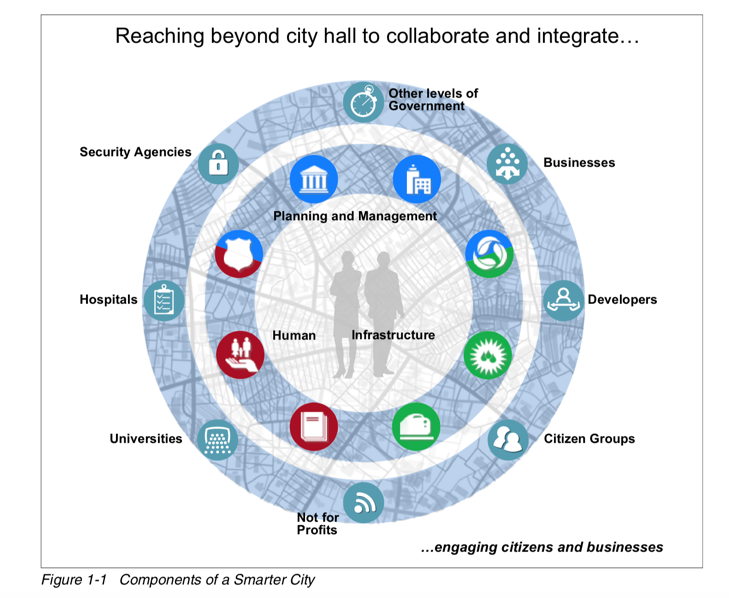

According to an IBM handbook for its IOC system published the same year, the Center is capable of combining vast quantities of information across city functions including “security agencies” and “other levels of government.”

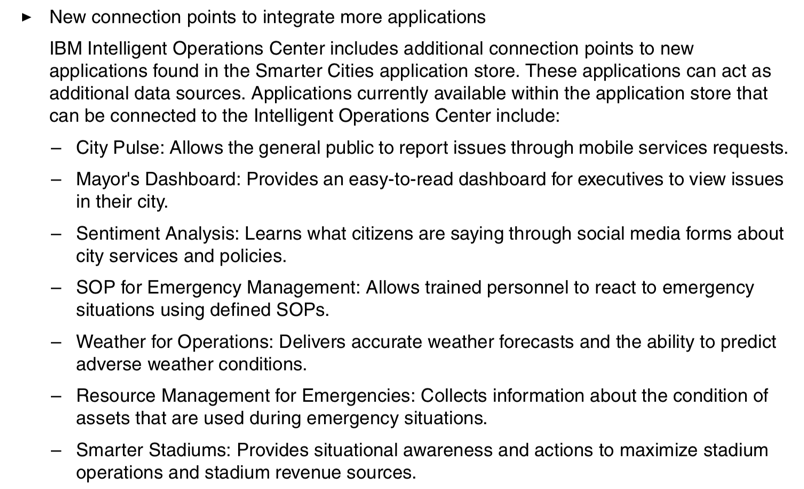

Sources of data include feeds from “weather, citizens, law enforcement, social welfare, video”, and the document identifies a number of applications which administrators can connect to the Center from an in-built store, including: “Sentiment Analysis: Learn what citizens are saying through social media forms about city services and policies.”

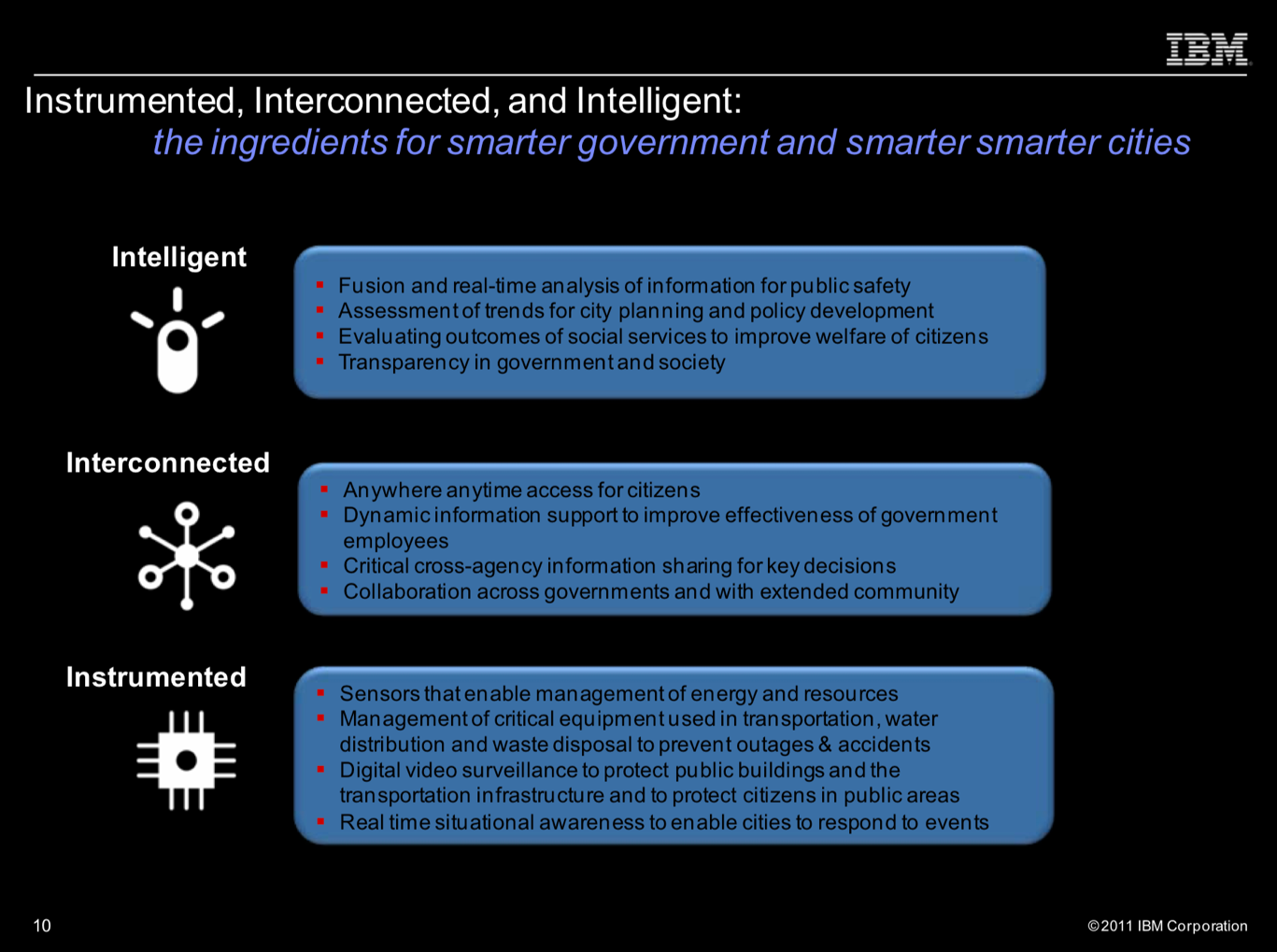

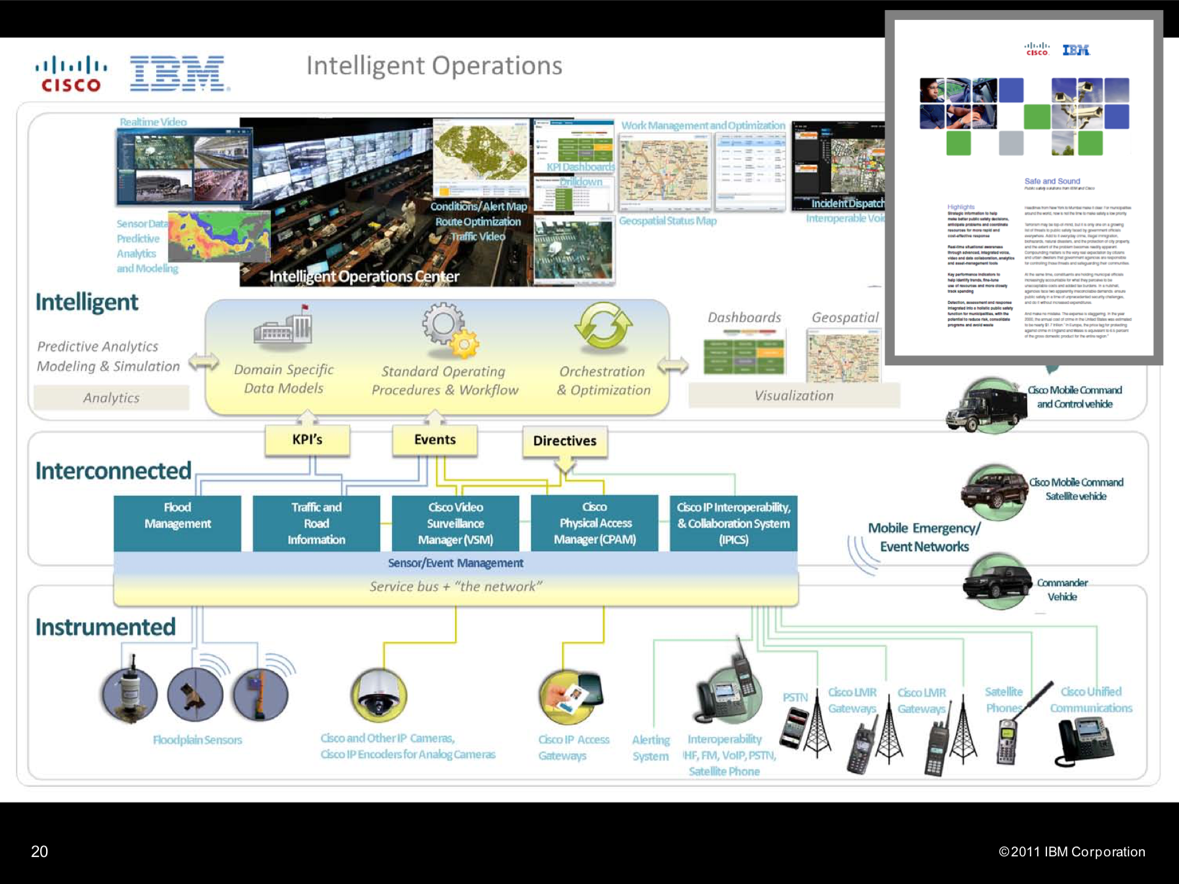

This represented fairly staple thinking on behalf of IBM’s ‘smarter planet’ vision. An IBM presentation deck from 2011 published on the Cisco website repeatedly mentions “public safety” as an integral component of IBM’s ‘smarter planet’ vision.

Apart from a bizarre slide describing how smart cities shift from “reactive to predictive to proactive” approaches — featuring an image of The Terminator no less — the IBM deck also mentions the importance of “fusion and real-time analysis of information for public safety” and “digital video surveillance to protect public buildings and the transportation infrastructure and to protect citizens in public area.”

A section on its IOC system describes “public safety” applications which include the capacity to “predict, monitor, and mitigate crisis situations”, “automatically analyze video streams for threats” and “analyze data to detect and act on criminal patterns.”

The deck incidentally also revealed the critical role played by Cisco hardware in creating the technological physical infrastructure managed by an IBM IOC system. Cisco provided and customized hardware for China’s notorious ‘Golden Shield’ censorship and surveillance program.

Laying the groundwork for China’s first police-state

Later that year, it was IBM that went on to establish Karamay as the first smart city pilot project in the Xinjiang region.

According to a 2012 IBM investor deck titled ‘Smarter Cities’, the company had established 82 IBM branches across the country encompassing research, innovation, and software development — including in Xinjiang’s emerging ‘smart city’ of Karamay. The document described IBM’s unique capabilities in China as involving “smarter cities”, “business analytics”, the “cloud” and “smarter commerce”.

Working with China Mobile, IBM made Karamay the first city in Xinjiang to enjoy a wireless communication system that would encompass all aspects of city life. According to China Daily, “The concept, proposed by IBM, is based on technologies such as the Internet of things and cloud computing, and embraces transportation, healthcare and public security.”

Ubiquitous surveillance was built-in to IBM’s design concept for Karamay from inception.The system was so sophisticated that it would be able to alert government officials when the unemployment rate became too high.

Publicly-available information on IBM’s work in Karamay is sparse. However, a 2015 report scoping global progress on smart cities commissioned by the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh throws some light on the ‘public security’ component.

The report, carried out by the Virginia-based ICF International — a highly reputed billion dollar global consulting firm — noted that IBM’s project established a platform that “can interconnect with the Police Geographic Information System (PGIS) to implement a wide assortment of smart services, including preventive maintenance of video, behavior analysis, facial recognition, video summary, quick search, image sharpening, and case investigation analysis.”

The year after IBM began work in Karamay, Huawei published a ‘Safe City Solution’ brochure identifying the city as a successful ‘safe city’ case study. The brochure described how Huawei had installed a “unified safe city platform” that would provide the same surveillance functionality for police as described in the ICF International report about IBM.

In short, while IBM created the initial design for Karamay’s ‘smart’ approach to public security, Huawei went on to build it.

I asked IBM about its relationship with Huawei at this time, and its involvement in establishing the foundations for the smart city infrastructure — especially on “public safety” — that has permitted the rapid expansion of mass surveillance across Chinese cities, but especially in the Xinjiang region.

Despite multiple requests for comment, and several assurances from an IBM spokesperson that answers would be forthcoming, in the end the company simply failed to respond.

According to Eva Blum-Dumontet, a smart city expert at London-based global privacy watchdog Privacy International:

“The model of smart cities as developed in Western countries — and to that extent it is worth remembering that the very term smart city comes from IBM — has often been extremely privacy invasive and about the systematic collection of citizens’ data. It’s no wonder now that other countries are doing the same. This is a pattern we unfortunately see too often with government surveillance: Western countries decide that a new system or a new law is acceptable since it all falls under the rule of law but we eventually see the very law or system being reproduced abroad, sometimes with worse consequences.”

Dance with the devil

Karamay was just the first project in a bigger plan which involved building 5,000 4G mobile stations across Xinjiang’s 16 main cities and 63 counties, in the first half of 2014 alone. By the end of that year, 12,000 4G base stations would be built.

By 2016, as the smart city infrastructure was expanded across Xinjiang, IBM was still operating in Karamay, and began introducing ‘cognitive IoT’ (Internet of Things) according to the city’s local government website. IBM’s technology was built around the Watson IoT platform, an AI system that can find patterns and relationships across vast amounts of different types of data. One of Watson’s other applications in China was with China Central Television (CCTV), which used the software to allow fans to track the Vaude-Tibet cycling challenge by measuring GPS, altitude, body temperature and heart rate via mobile devices.

According to IBM’s Kevin Larson, the platform’s power lies in its ability to ingest and analyse any form of data, in almost any format, and to search for correlations with other types of data. It can do this across weather data, scientific articles, fleets of vehicles, environmental sensors, or audio-visual feeds. This makes the platform extraordinarily well-suited for a wide range of surveillance applications, including examining video and photos to identify scenes and patterns that can connect people and events, as well as examining text from transcripts of customer calls, blogs, blog comments, and tweets — once again, doing so in a way to correlate information and detect patterns.

How exactly the Watson platform was practically applied in Karamay, and Huawei’s access to Watson, is unclear — and spokespeople from both IBM and Huawei offered no clarifications. But the city is home to many Uighur ‘re-education’ camps, whose inhabitants are often picked up by police for wearing ‘Muslim clothing’ or ‘long beards’. The city’s extensive surveillance networks — first established under IBM’s “public security” platform, which evolved into Huawei’s ‘Safe City’ program — make such practices far more automated.

Under the program, Huawei supplied technology to Karamay authorities combining video surveillance with AI and Big Data, providing what the company calls “a converged, visualized command solution for government agencies to flexibly share video resources and collaborate in the tracking of suspicious individuals.”

Screenshots about Huawei’s involvement in mass surveillance from its official website were circulated on Chinese social media last December. The material was apparently not readily available on Huawei’s site, and only accessed by activists by registering an account and logging in. However, elsewhere on the Huawei website, company representatives are fairly forthcoming.

“The Huawei Safe City project is a significant contribution to Karamay building a world-class public safety infrastructure”, writes Huawei executive Viktor Yu on the company website. “The project supports city-wide access to hundreds of camera feeds that enable thousands of police officers to effectively monitor the safety and security of a population of nearly 300,000.” Yu continues:

“Using the massive amount of accumulated crime data over the past decades, the command platform has pre-integrated a variety of early warning scenarios. When exceptions are detected, the analytics platform automatically generates a prioritized alert. The affect is a broad reduction in the rates of crime committed and the broad maintenance of social stability.”

Over the last decade, Huawei has established dozens of Safe City programs across China in cities including Shanghai, Jiangsu, Guangdong and beyond.

In May 2018, Huawei continued its work in Xinjiang with a new partnership with the Public Security Bureau in the Xinjiang capital of Urumqi, establishing an “intelligence security industry” innovation lab. The lab would create a cluster of expertise for the region to “unlock a new era of smart policing and help build a safer, smarter society,” according to Huawei director Tao Jingwen on the company’s website.

Among the technologies now being applied in Xinjiang is advanced facial recognition designed to search exclusively for Uighurs based on their appearance, potentially ushering in what the New York Times describes as “a new era of automated racism”. Huawei did not respond to questions about its role in supporting the emergence of such technologies via its work in Urumqi.

The relationship between IBM and Huawei in Karamay is opaque, but both companies operated in the city during the same period to transition it into a ‘smart city’: one of whose results was the creation of a deeply intrusive surveillance apparatus that props up systematic human rights abuses.

Whatever the nature of this intersection, Huawei’s tremendous growth would have been impossible without significant support from IBM. As early as 2000, IBM signed an agreement with Huawei providing it with unprecedented access to its microelectronics division’s R&D facilities.

“Collaborating with IBM will enable Huawei to have faster access to the advanced networking technologies we need to quickly deliver high-end telecommunications equipment to our customers across the world,” said William Xu, then senior vice president of Huawei Technologies, at the time.

There is no indication that this agreement between IBM and Huawei ever ended, and neither company took the opportunity to deny an ongoing relationship.

IBM’s close relationship with Huawei has continued until recently according to a 2016 China Daily interview with Huawei’s founding chief executive Ren Zhengfe. The interview confirmed that Huawei pays IBM annual consulting fees of over $100 million:

“Every year Huawei spends more than $100 million inviting IBM’s consultant team to help manage the company,” the Communist Party paper pointed out — “why such a big investment?”

Zhengfe’s reply was that the price is worth it: “Starting from producing products worth about 10,000 yuan, we moved up the value chain to make products worth tens of billions of dollars to hundreds of billions of dollars. With their help, Huawei is making steady progress, so every year we are spending more than $100 million on consulting fees.”

Friends in high places

A 2017 edition of Huawei’s self-published ICT Insights magazine focused on its Safe City program included fawning contributions extolling the program’s benefits from Accenture, Boston Consulting Group, the British Association of Public Safety Communications Officials (BAPCO), and IHS Markit.

In the same year, Huawei signed agreements for its Safe City program for video analytics and facial recognition technologies produced by three companies: Agent Vi, an Israeli firm one of whose investors is the US-based telecoms giant Motorola Solutions; Ipsotek, a British security firm specialising in intelligent video analytics that is accredited by the British government’s Home Office; and Xjera Labs, based in Singapore, which was recently described as having created “the world’s most sophisticated facial recognition system” by Business Insider.

The signings took place at a Huawei-sponsored forum at a global Interpol conference supported by the World Economic Forum.

For national security expert Dr Anders Corr, a former US military intelligence analyst for United States Pacific Command (USPACOM) and the United States Special Operations Command Pacific (SOCPAC), among other agencies, such partnerships and investments are to be expected. But since they pose serious potential risks, better government regulation is the only redress.

“Western and allied corporations have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize shareholder value. Expecting these companies to act according to any other ethic is misguided,” said Corr. “This is why we need government to regulate our corporations to protect national security, personal liberties and human rights, including the human rights of Chinese citizens.”

In reality, the opposite has happened. Despite the Trump administration’s frequently stated hostility toward Chinese tech firms, for instance, the US government has long encouraged American companies to capitalize on China’s digitalisation drive.

And it’s not just previous administrations. In the summer of 2017, Donald Trump’s own Department of Commerce published a country guide for US companies who want to invest in China, identifying investment opportunities across Big Data, IoT, AI, cloud computing, and “smart city development”.

“Smart city systems are managing traffic, stabilizing electric grids, allocating and coordinating emergency services, and providing more city information to people and managers than has ever been available before,” the document enthuses. “Foreign companies have the opportunity to leverage technological, operational and management advantages to participate in smart city construction in areas such as smart governance, smart industry and smart public services.”

Three months later, Trump’s Commerce Department partnered with the Chinese government-funded Shanghai Pudong Smart City Research Institute to host the ‘US-China Smart Cities Forum’ in Shanghai.

Describing China’s smart city market as a $300 billion opportunity, an official invite brochure for the event calls on US firms to get involved:

“As a leader in smart cities technology, US technology and service providers are uniquely positioned to capitalize on this new shift in China. Smarter technologies will help China tackle urban challenges, creating unparalleled opportunities for innovative US technology and service providers.”

The British government has also attempted to capture China’s attention, providing direct funding through its China Prosperity Strategic Program Fund (SPF) for joint smart city projects in both UK and Chinese cities.

The project introduced British firms “into the Chinese smart city market”, but also sought to leverage research on Chinese smart city practices for implementation at home. In 2018, the UK government hosted a British business delegation to China’s Greater Bay Area to facilitate pitching to local Chinese clients on smart city development.

Corr attributes the fascination with China to a democratic deficit that strikes at the heart of Silicon Valley’s relationship with governments. Tech companies now have “extraordinary influence in our governments, through corruption of our politicians, including by campaign donations and a revolving door between business and government positions. They also influence government because they can leave one jurisdiction for another. They can threaten to offshore their profits and job provision as a threat to decrease regulations that counter their profit motives.”

Microsoft and Huawei, sitting in a tree

Another US tech giant which has had few qualms about profiting from China’s mass surveillance drive is Microsoft.

In March 2019, Microsoft was accused of partnering with the Chinese firm SenseNet, which monitors Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, by allowing the company to run its controversial biometrics surveillance technology on Microsoft Azure Cognitive Services — a relationship which was eventually denied by Microsoft.

Whatever the truth of that case, like IBM, Microsoft’s role in China’s surveillance cities is more subtle and insidious.

In April 2019, Microsoft launched its third and largest ‘AI and IoT Insider’ lab in Shanghai’s Pudong New Area to work with unspecified Chinese firms and multinational companies. The lab was slated to build prototypes to support “digital transformation” across industries including manufacturing, retail, healthcare, and the “public sector” — which of course entails any services run directly by government authorities, potentially including police and security agencies.

Many of Microsoft’s smart city projects in China are clearly benign. One is an urban air quality project with the Beijing government and Ministry of Environment Protection to use big data for monitoring and forecasting air quality. In another project, Microsoft is working with the Wuhan government to use a chatbot to answer routine citizen questions on city services, such as how to obtain a driver’s license.

This is the culmination of years of engagement. In 2014, Microsoft had signed a range of cooperation agreements with several Chinese provinces and cities, including Yunnan, Zhuzhou, Changchun, Yangzhou, and Wenzhou, as part of the firm’s CityNext initiative to develop them into smart cities.

There is no evidence that with these initiatives, Microsoft has worked specifically on surveillance-related projects directly with the Chinese government.

But in 2016, Microsoft’s China subsidiary delivered a seminar for the Ministry of Public Safety at the firm’s China Center One facility in Beijing, showcasing “public safety” solutions. A candid description of the seminar by Arthur Thomas, Microsoft’s managing director for public safety and national security, is available on Microsoft’s website.

“Microsoft has the right analytics solutions for assessing potential emergencies, determining their projected impact, and then facilitating the execution of incident action plans,” explained Thomas. “We do so by combining information from different sources (e.g., location, tracking, sensors, video, traffic reports, hospital status, weather reports, social media, and other dynamic data) with GIS data (e.g., imagery, elevations, streets, and critical infrastructure).”

I asked Microsoft if the company highlighted any concerns to Chinese authorities before planning to provide technology to an authoritarian state implicated in the repression of dissidents and minorities. Microsoft declined to comment.

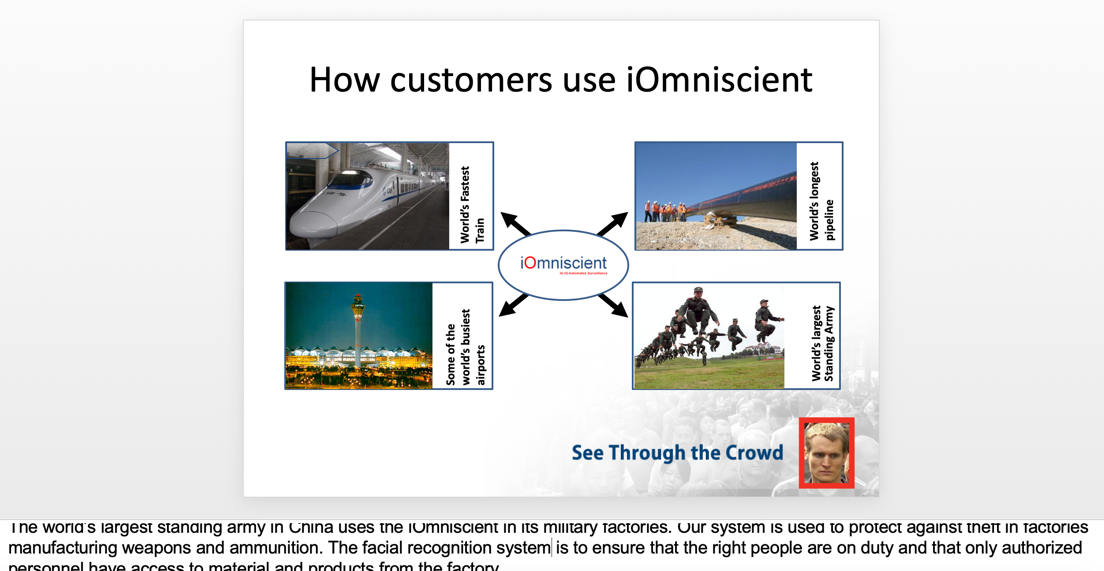

One of Microsoft’s technology partners at that seminar was Australian company iOmniscient. The firm has provided video surveillance and analytics technology to Chinese cities, including for the Chengdu rail metro service and for Chinese military factories.

“The world’s largest standing army in China uses the iOmniscient in its military factories,” reads an iOmiscient company and product presentation deck. “The facial recognition system is to ensure that the right people are on duty and that only authorized personnel have access to material and products from the factory.”

Indeed, Huawei’s involvement in providing repressive surveillance technology did not prevent Microsoft from working in close partnership with the Chinese firm in recent years.

In 2017, Microsoft signed an agreement with Huawei to “initiate in-depth cooperation on the public cloud” by building an “open and win-win ecosystem.” The agreement would bring Microsoft enterprise services over to the Huawei cloud. The following year, the two companies launched a joint cloud solution based on Microsoft’s Azure Stack software.

The following year, Huawei continued to ramp up its support for state surveillance in Xinjiang. Huawei partnered with a police department in Xinjiang’s Urumqi (the capital of Xinjiang province) to establish a ‘smart city’ security solution. Official statements from the Xinjiang Public Security Bureau confirmed that Huawei would contribute to the human technical expertise necessary to “meet the digitization requirements of the public security industry.”

This appears to be only one example of a much wider programme of complicity. Toward the end of last year, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute found that:

“Huawei’s work in Xinjiang is extensive and includes working directly with the Chinese Government’s public security bureaus in the region… Huawei’s Xinjiang activities should be taken into consideration during debates about Huawei and 5G technologies.”

Microsoft did not want to comment when I asked whether they had factored in the ethical issues of working with a Chinese firm building the largest surveillance regime in the world.

Huawei, Huawei, everywhere

Huawei’s burgeoning love affair with the British government is only its latest success. The firm’s official literature on the safe city program now claims to have exported the model to over 230 cities around the world on every continent.

Among the early adopters of Huawei’s safe city solutions have been countries with a history of authoritarianism and internal violence, including Russia, Pakistan, Laos, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. In Serbia, Huawei was contracted for public safety in the capital of Belgrade, where its installation of facial recognition cameras systems has been heavily criticized by digital rights watchdog the Share Foundation for violating citizen privacy laws.

And while the Boris Johnson government has made much of the notion that it is not allowing Huawei to access “security critical” infrastructure, this is already happening. “Huawei’s importance to the UK’s critical national infrastructure is nothing new,” said David Bicknell, principal analyst at GlobalData’s Technology Research Team. “It has been working on government projects since 2003 and hired the country’s top IT specialist, John Suffolk, in 2011… the company has become so deeply embedded into the UK’s telecoms market over the last two decades that the government is willing to risk a public confrontation with a major ally rather than excluding Huawei from work on the UK’s 5G network.”

But Huawei technology is already being used for some of the most sensitive infrastructure in the UK and Europe, due to its agreement with trusted third party suppliers.

In 2017, Huawei signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Frequentis, an Austrian technology firm specialising in the supply of communications and information systems for government agencies that provide public safety services. That includes, according the company’s press materials, “Air Traffic Management (civil and military air traffic control, and air defence) and Public Safety & Transport (police, fire and rescue services, emergency medical services, vessel traffic and railways).”

According to an announcement on Huawei’s website, the partnership with Frequentis would promote “the joint development of an open ecosystem for public safety solutions, in a move set to usher in safer cities.” The two firms would create “a Next Generation Dispatching Solution for Command and Control centres.” The announcement continues:

“By supporting features such as seamless integration of consultation and surveillance systems across different agencies, real time voice and data transmission services, the joint solution will help public security agencies achieve greater efficiency, while reducing their total cost of ownership for mission-critical IT investments.”

Frequentis provides its technology solutions to over 140 countries including the US, UK and across Europe, making it the world’s top provider of voice communications systems. Its customers include the UK Ministry of Defence, London Metropolitan Police, NASA, the US Navy, the Australian Royal Air Force, the Swedish Maritime Administration, and Eurocontrol, which is working on the European Commission’s ‘Single European Sky’ project to create the first pan-European voice communications system for air traffic control.

The announcement asserts that the market for the technology that will emerge from Frequentis’ partnership with Huawei is near global, covering Europe, the Middle East, Africa, the Asia Pacific and Latin America. Frequentis did not respond to request for comment.

Like all the companies approached for this investigation, Huawei too ultimately failed to respond to my questions — despite initial responses and repeated assurances. None of them were willing to be put in the dock about their role in facilicating the rise of what has become not only the biggest mass surveillance operation in history, but one that is now complicit in cultural genocide.

As Huawei continues its steady infiltration of telecomms, security, surveillance and other critical technology infrastructure around the world; as governments kowtow to its technological prowess — it’s worth remembering how it has honed and finessed its capabilities: with the blood and bodies of China’s repressed Uighur minority.

This story is based partly on my earlier investigation for Coda Story.