Economic growth isn’t coming back. While some level of growth might continue in coming decades, the boom era of seemingly unlimited material throughput we became accustomed to in the middle of the twentieth century is unlikely to ever return again as we enter a fundamentally new age of diminishing returns.

These are the conclusions of a new working paper by leading ecological economist Professor Tim Jackson, Director of the University of Surrey’s Centre for Understanding Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP).

And the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) is taking notes.

An earlier draft of the paper, notes Jackson, was “prepared as input into the UK Global Strategic Trends Review”, a forecasting research programme run by the MoD’s Defence Concepts and Doctrines Centre (DCDC), which every few years produces an updated Global Strategic Trends report for the MoD and wider UK government. Jackson also acknowledges feedback from MoD officials in revising that draft to create the concurrent version.

Jackson is former Economics Commissioner for the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission. From 2010 to 2014, he was Director of the Sustainable Lifestyles Research Group, funded by the UK Department for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Scottish Government, and the Economic and Social Research Council. He also advised many other government departments, and held advisory roles for the UN Environment Programme, the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the UN Industrial Development Organissation, the European Environment Agency, the European Parliament, and the New Zealand Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

The long crisis

Professsor Jackson’s paper examines a range of new data suggesting strongly that chronically low rates of economic growth in recent years since the 2008 crash, far from representing a temporary phase soon to be overcome by a resounding ‘recovery’, are in fact a ‘new normal’ — from which the global economy may never truly recover.

“There remains a disturbing possibility that the huge productivity increases that characterised the early and middle twentieth Century were a one-off, something we can’t just repeat at will, despite the wonders of digital technology,” writes Jackson:

“A fascinating — if worrying — contention is that the peak growth rates of the 1960s were only possible at all on the back of a huge and deeply destructive exploitation of dirty fossil fuels; something that can be ill afforded — even if it were available — in the era of dangerous climate change and declining resource quality. Low (and declining) rates of economic growth may well be the ‘new normal’.”

Jackson draws on a number of prominent economic voices in putting forward his diagnosis, most of whom are widely respected. He cites former World Bank chief economist Larry Summers, for instance, who has recently observed:

“The underlying problem may be there forever.”

Different economists emphasise different causes for the phenomenon. Some point to problems with “sluggish demand”, a deeper reluctance from business and consumers to invest and spend due to new economic uncertanties. Others, like US economist Robert Gordon, point to a supply challenge relating to an escalating decline in the pace of industrial innovation and productivity.

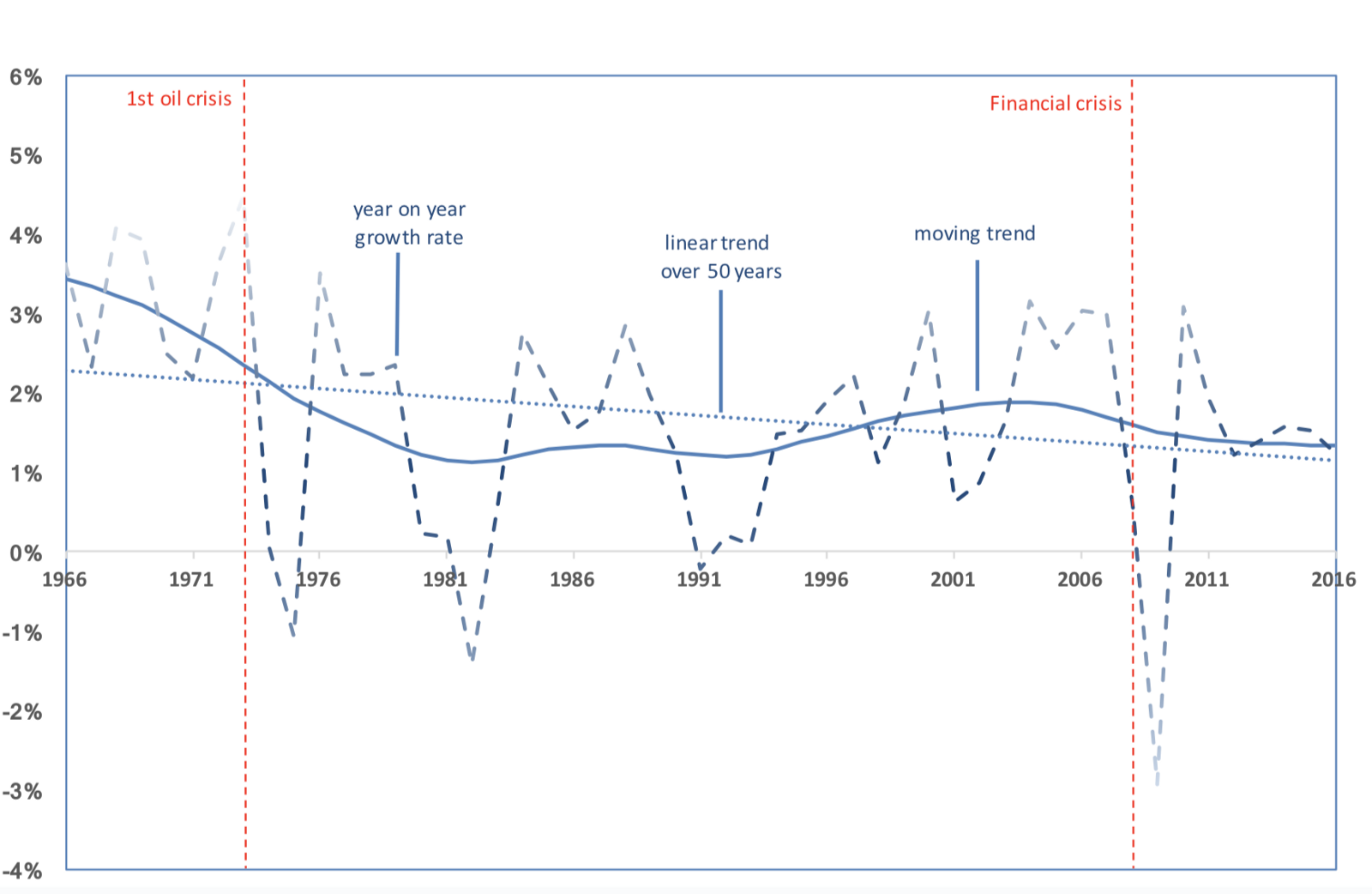

Whatever the underlying drivers of the problem, Jackson shows that the phenomenon is very real — the 2008 financial crash was indeed a major catalysing event. But it was only a particularly bad blip in an unmistakeable long-term downward trend for the rate of global economic growth.

In 1996, the trend rate of growth in the global GDP was 5.5%. By 2016 it was little more than 2.5%.

‘Advanced’ economies trending to zero growth in a decade

When Jackson breaks down the data regionally, the picture is more complicated. After the financial crisis, some of the poorest economies in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia had per capita growth rates below 1% per annum. But in emerging markets like China, India and Brazil, economic growth rates had overtaken growth rates in more advanced economies such as the OECD countries.

Extrapolating the current downwards trend forward has some interesting results:

“Whereas for the global GDP per capita, the point at which growth disappeares is more than 60 years into the future, for GDP per capita in the OECD nations, the point is brought forwards dramatically. In less than a decade, on current trends, there would be no growth at all in GDP per capita across the OECD nations.”

As an indicator of how bad things are looking, Jackson focuses on trends on labour productivity growth. First of all, he looks at the OECD, where we see plummeting rate of productivity growth since the 1970s.

If we extrapolate this trend forward, labour productivity growth would reach zero by 2028.

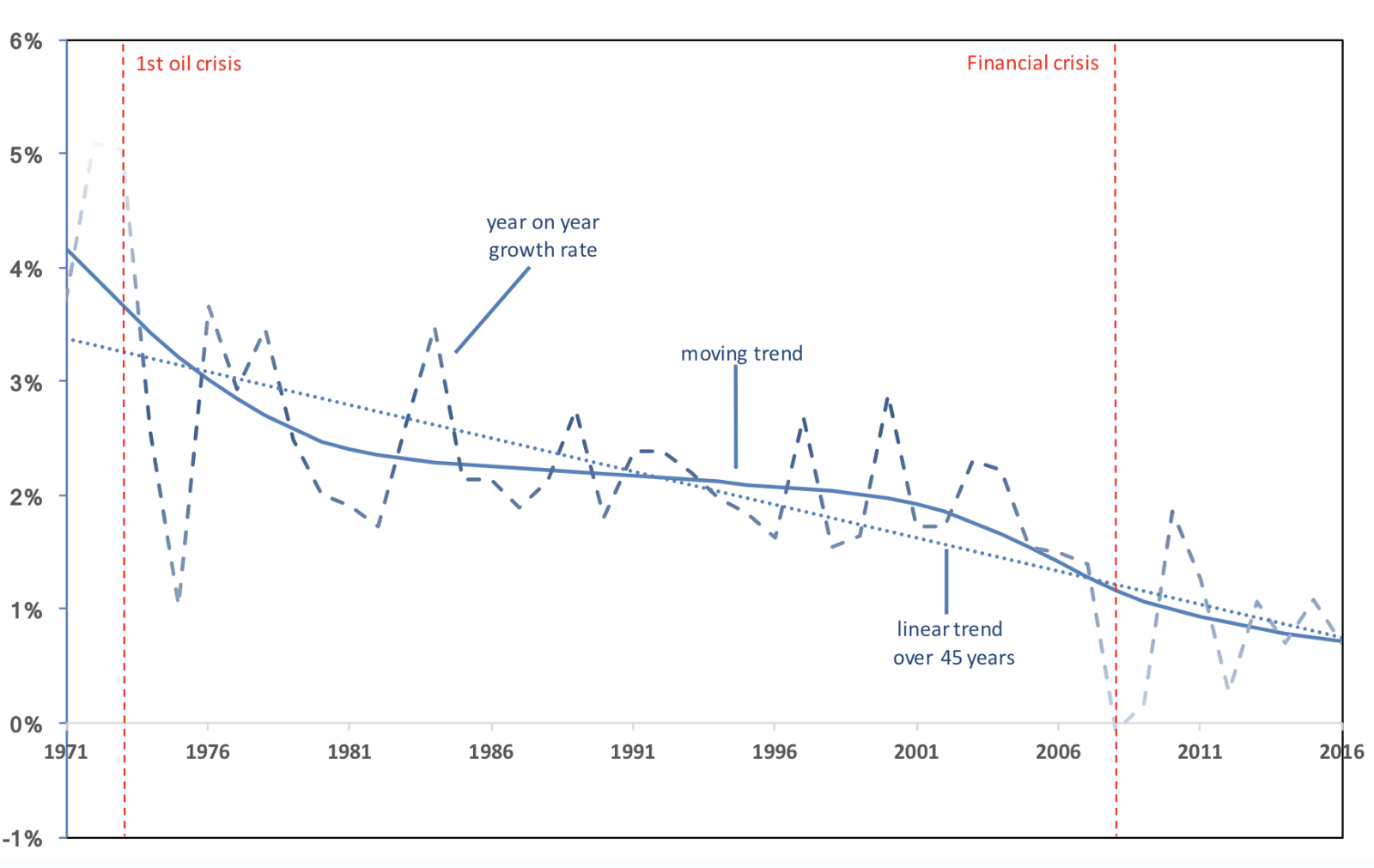

Then Jackson looks at the UK, a particularly useful case study of the future pathways of industrial development due to being one of the world’s earliest industrialisers.

The data shows that the peak of Britain’s labour productivity occurred between the 1950s and 70s, after which it declined quite steeply, reaching extraordinary low levels after the 2008 crash which are even lower than pre-1900 levels.

Political instability

We are already seeing the destabilising social and political impacts of this situation. The rise of Trump, his turn to neo-fascist policies toward Black and ethnic minorities, immigrants and Muslims, and his alliance with far-right extremist networks in Europe — all driven by an alarming resurgence of populism across both sides of the Atlantic — are direct symptoms of a new economic reality of slowly dying growth:

“Electorates tend to punish administrations badly when social investment falls. If declining growth is met with fiscal austerity it is likely to lead to progressively worse social outcomes and increasing political fragility.”

At the root of the political instability we are seeing in the world, Jackson suggests, is the breakdown in the dynamics of “the existing growth-based paradigm.”

This old dying paradigm is driving environmental damage, exacerbating social inequality and contributing to increased political instability.

Net energy decline

Jackson then goes further, stepping outside of economic orthodoxy to point out the striking evidence of a correlation between the long-term decline in economic growth and underlying resource constraints:

“The suggestion that the rise and fall of productivity growth is associated with the availability of physical resources such as energy and minerals is clearly one that merits further attention. The similarity between the rise and fall in labour productivity shown… and some recent studies of the energy return on energy invested (EROI) in fossil fuels is striking.”

EROI is a measure of the amount of energy used to extract energy from a particular resource. The more energy one can get out compared to what is put in, the better, and the higher the ‘net energy’ available to society. Lower EROI, however, means that less and less energy can be extracted despite increasing investments of energy.

Recent economic research previously reported by INSURGE suggests that the maximum EROI levels for global oil and gas production were reached around the middle of last century.

“Most EROI studies across multiple countries show declining EROI in the last two to three decades,” says Jackson. “So the idea that the rise and fall in labour productivity growth has something to do with the underlying physical resources is certainly not fanciful.”

There are strong grounds then to recognise that the long-term decline in the rate of economic growth is partly related to industrial civilisation’s intensifying exploitation of material resources on the planet, and the diminishing returns from doing so.

The economic crisis is not just about ‘economics’, narrowly conceived: it is about the human species’ accelerating breach of planetary boundaries.

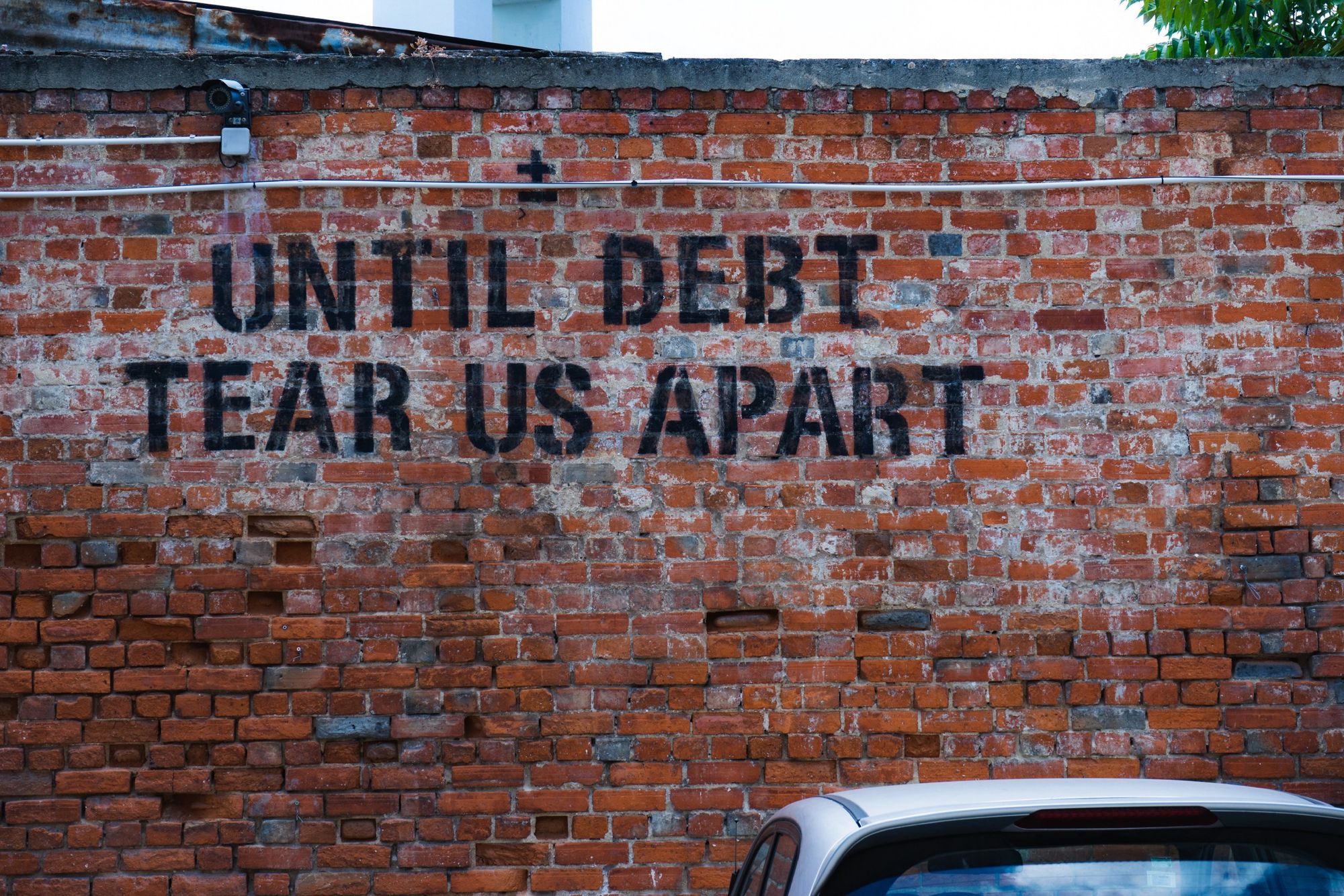

The debt machine

But Jackson points out that declining EROI is unlikely in itself to be the sole driving factor in this broader trend of declining economic growth, which will also be intimately related to a combination of supply and demand issues within the economy.

Among those issues is that to keep growth growing, industrial economies have sought to financialise their economies, even more so as they deal with rising costs of material production. The idea is to increase “liquidity”, spending power, by essentially creating more cheap money — which in simplified terms means flooding the economy with credit. This temporarily lubricates spending power in the economy, but at the cost of expanding levels of debt.

“This has tended to stimulate speculative investment at the expense of productive investment in the real economy,” says Jackson. It also means that the global economy is increasingly unstable, with growth hinging very much on the expansion of debt whose repayability is in question.

And that has meant that this concurrent structure of economic growth has inevitably benefited a tiny rich minority, who sit at the helm of this parasitical financial system — while the vast majority of the world’s poor have seen little or negligible benefits.

What Jackson then shows is that the neoliberal story of growth that has accompanied these processes in recent decades has seen a dramatic increase in structural inequality.

Gutting the poor, working and middle classes

From 1980 to 2014, average income growth in the US was only 1.4%, already quite low overall.

“But the striking part of the story was the reversal in the fortunes of the poorest and richest as beneficiaries of that growth,” observes Jackson.

The bottom 50% of Americans saw their income grow “at a meagre 0.6%, only half the average rate of growth of the economy as a whole. Meanwhile, the incomes of the richest 5% “grew at 1.7% per annum, significantly above the average income growth.” Increasingly, the super-rich benefited from the tepid growth being squeezed out of the planet:

“The average growth rate of the top 0.001% of the population was over 6%, allowing them to increase their post-tax earnings by a factor of seven over the last three decades. The poorest 5% saw their post-tax incomes fall in real terms over the same period.”

This sharp rise in inequality illustrates how the poor, working and middle classes have been gutted — with even reasonably well-off working professionals experiencing an overall unprecedented decline in their purchasing power.

Faced with such diminishing returns, powerful economic producers and shareholders have “systematically protected profit by depressing the rewards to labour.” This has been exacerbated by governments pushing forward fiscal austerity, deregulation, privatisation and liberalisation along with “loose monetary policy”:

“The outcome for many ordinary workers has been punitive. As social conditions deteriorated, the threat to democratic stability has become palpable.”

Rather than rising inequality being an inevitable result of a decline in the growth rate, Jackson argues that rising social-financial instability and inequality result directly from “trying to protect the growth rate in the face of an underlying decline in productivity, by privileging the interests of the owners of capital over the interests of those employed in wage labour in the economy.”

In other words, trying to keep the growth machine growing when the machine itself is running out of steam is precisely the problem — the challenge is to move into a new economic model entirely.

Wither the Singularity?

Having demonstrated an alarming correlation between efforts to accelerate growth at all costs and the systemic deepening of economic inequalities, Jackson goes on to show that an effort by business and government to adapt to the reality of a post-growth economy may hold the best prospects for more equal and prosperous economies of a different kind.

The problem with business-as-usual, he points out, is that it is based on assumptions for which the evidence is rather thin.

The idea is that productivity growth will return, driven chiefly by technological breakthroughs either in low carbon technologies, or in “increased automation, robotisation, artificial intelligence” — or by some combination of both.

In other words, technology, at some point, will save the day. The most explicit variation of this circulating today is the idea of the Singularity — which is when artificial intelligence (AI) reaches a level of super-intelligence that will drive exponential, runaway technological growth, that in turn will solve all our problems.

But in reality, it’s simply not clear that techno-focussed investment strategies alone will actually lead to the hoped for outcomes. The low-carbon revolution is not, as yet, actually taking off. The Paris Agreement still lacks any tangible delivery plans. And it’s not clear that low carbon technologies, even if viable, can simplistically substitute for fossil fuels with the same levels of growth industrial civilisation is accustomed to.

As for AI-driven automation, it is widely recognised that its social consequences might be devastating. It involves essentially replacing workers with technological material assets owned centrally as capital. This means it is not only likely to require increased material inputs and therefore have a higher resource footprint, it is also likely to create “an unequal and increasingly polarised society”:

“There is a real danger that new digital and robot technologies will remove the need for whole sections of the working population, leaving those who don’t actually own the technologies without income and without bargaining power. Meanwhile the owners of these technologies are likely to acquire unprecedented market power, and the conditions for ordinary workers will deteriorate even further.”

Like others, Jackson suggests a Universal Basic Income as a potential mechanism to address this mass disenfranchisement of workers. But there remain serious unanswered questions over how governments committed to austerity in an era of diminishing resource and productivity returns would be able to afford this.

More usefully, Jackson calls on governments, businesses and communities preparing to respond to these issues to begin actively adapting to the underlying drivers of an emerging new economic reality.

Pointing to new research on de-growth and ‘post-growth’ economics, Jackson notes that these approaches increasingly accept that endless “economic growth is neither desirable nor indeed feasible” for the world’s most advanced economies.

If these approaches are not pursued, then we are faced with the probable impacts of business-as-usual

“In a growth-obsessed world it is easy to end up overlooking the parts of the economy that matter most to human wellbeing. By understanding and planning for the conditions of the ‘new normal’ associated with low growth rates, it is possible to identify more clearly the features that define a different kind of economy. A simple shift of focus opens out wide new horizons of possibility.”