A trans-Atlantic network of Conservative and Libertarian think tanks were caught creating ‘shadow trade deals’ which deregulate in favour of food and drug lobbies during Brexit. In this investigation, Kam Sandhu exposes the long history of this trans-Atlantic network, and its efforts to drag us towards corporate freedom at the expense of public safety since the birth of neoliberalism. The network now sees an opportunity to enact significant changes during Brexit, aided by the duplicity of business interests in public discourse. The British public needs to get a grip on the future we want.

I’m sure you all know the story of how you came to be here’, Brexiteer and Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan addressed a packed room at the Capitale, New York on November 8 as he delivered the Toast to Freedom for the Atlas Network:

‘Gallus Gallus Domesticus….the chicken should be the symbol of the global freedom movement.’

Surrounded by a room full of ‘freedom champions’, Hannan used his speech to attack EU regulations which prevent US food staples such as chlorinated chicken, hormone fed beef and Genetically Modified (GM) foods from sale to the UK.

These were not the demands plastered on the sides of buses during the EU referendum — during which Hannan was spokesperson for the official Vote Leave campaign. Instead, they have become Hannan’s main aims since the Leave victory, with rhetoric of new ‘opulent markets’ and using Brexit as a deregulatory mechanism: the core tenet of the ‘freedom movement’.

Connected to 450 free market think tanks across the globe, the Atlas Network is a powerful libertarian group funded by, amongst others, Exxon Mobil and the Koch Foundation (belonging to the billionaire Koch brothers).

Its overarching goal is ‘defeating socialism at every level’ according to SourceWatch, through the export of its business-friendly rhetoric and government-limiting ambition worldwide. Its history reveals a ground and state-level war in the name of market liberalisation employing dark money, astroturf groups and think tanks to create a common sense environment in favour of profit, deregulation and absolute corporate freedom.

The network was founded by Anthony Fisher, a British Eton-educated businessman who made his money from US-style intensive chicken farming.

During a trip to the United States in 1952 Fisher was introduced to new techniques which he brought home to his first battery cage farm — introducing the US broiler chicken industry to the UK.

He went on to make millions from his company, Buxted Chicken. With this wealth, and under the instruction of free marketeer Frederick Hayek that think tanks were the best way to guard against socialism, Fisher founded the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA) in 1955.

The London-based IEA is the ‘grand-daddy’ think tank of the Atlas Network. Praised with providing the intellectual groundwork for Thatcherism, its work inspired the evolution of the wider Atlas organisation in 1982.

This chimed with Ronald Reagan’s policies in the US. Husbanded by deregulation promoted by rightwing think tanks, this set in motion a step-change in groupthink — with a powerful intellectual network pushing forward an inherent value in market liberalisation which demonised regulations (including safety standards, liability, worker and consumer protection) as burdensome red tape that obstructed economic freedom.

Prominent think tank pushers in the US, now members of the Atlas Network, include the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) who led a successful, ultra-moneyed counter attack by the business community on the public interest era that came before.

Thomas O McGarity, author of Freedom to Harm: The Lasting Legacy of the Laissez Faire Revival, explains that these assaults on regulation:

‘… seemed to come from multiple institutions and had a strong ideological component…after the 1980 [Ronald Reagan] election the assaults were coming from the White House and from within the agencies as well as from the regulated industries and think tanks.’

Heritage and the AEI were used to funnel people into Republican administrations and beyond, spreading the movement’s maxims into economics and law professions. By making themselves available to politicians and media for sound-bites, the movement had an important hand in producing the dominant theory of neoliberalism as we now understand it.

Today, Heritage is at the centre of power. The Foundation had unparalleled access to the Trump transition team and are credited with writing the blueprint for Trump’s economic policy, including his recent tax cuts.

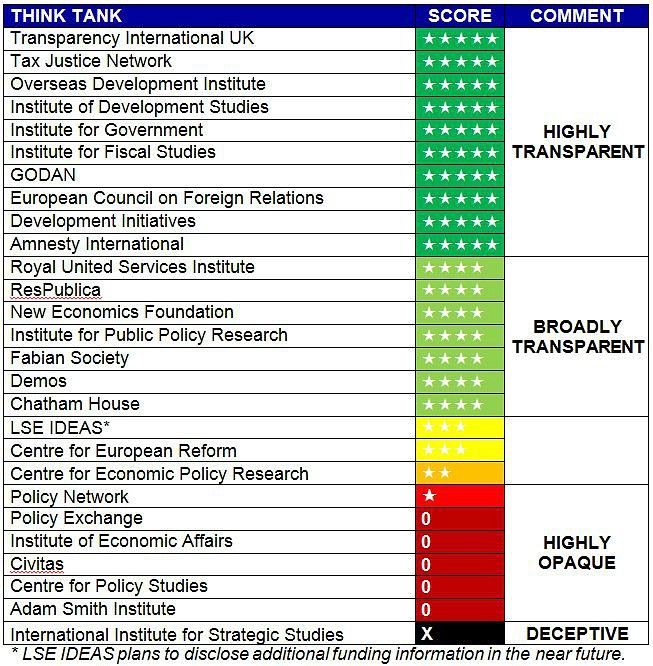

The IEA remains prominent in the UK too, described by Andrew Marr as ‘undoubtedly the most influential think tank in modern British history’. Along with the UK-based Adam Smith Institute (ASI), both are regulars on news and current affairs programmes, parroting their business-friendly deregulatory rhetoric, despite being the most opaque think tanks in the UK when it comes to funding.

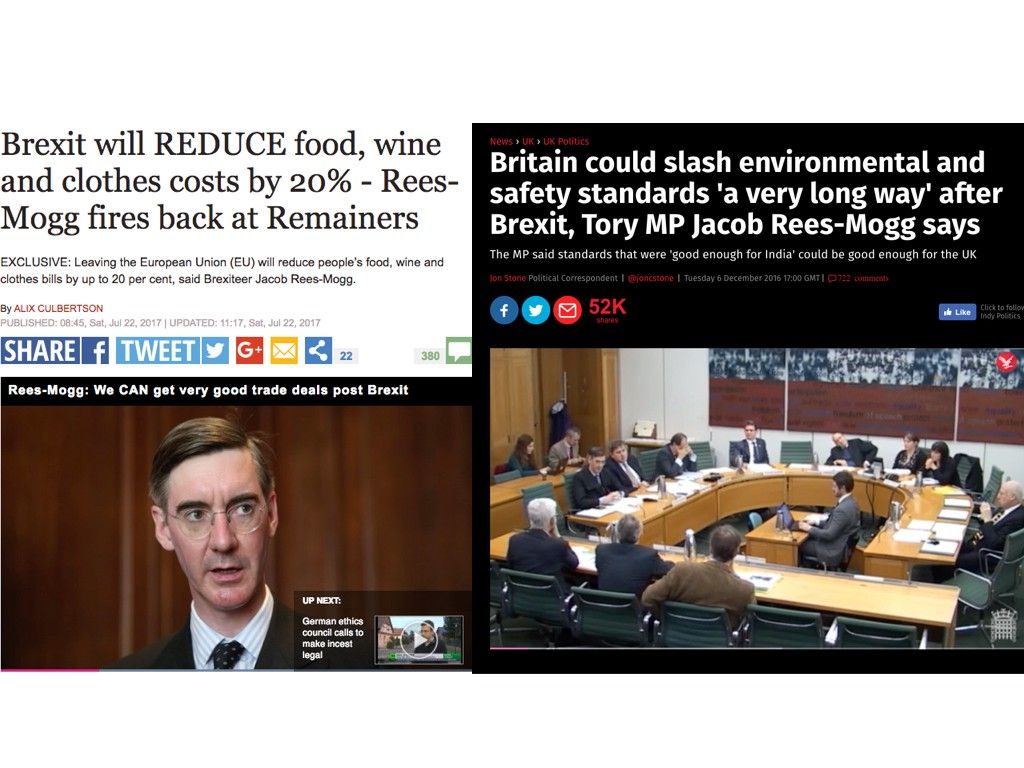

Despite that, they are hardly secretive about their economic agenda. IEA Director Mark Littlewood has explained that he voted for Brexit because it ‘was a significant opportunity for deregulation’, while the ASI has produced reports since the referendum enunciating the benefits of cheap chlorinated chicken.

The movement senses new opportunities for an era of favourable policies under Trump, Brexit and a potential US-UK Trade deal. Cheap chicken, it seems, is once again symbolic of the potential gains.

But there is a real cost to cheap chicken for all, that none of these think tanks and politicians are admitting. And the US broiler industry today is an example of the ideology’s most rabid excesses.

The Cost of a Chicken in Every Pot — The Broiler Industry

The broiler chicken is king in US poultry production. Specially bred for meat consumption, they are the drivers of the sector’s industrialisation and cheap prices.

Flocks take five to six weeks to be ready for slaughter. Breeding programmes are used to facilitate rapid growth of flocks, and maximum fattening of the bird.

As America’s most consumed meat, cheap chicken holds political value in Washington. The persistent growth of the industry over recent decades means lawmakers are keen to show they are on the side of business when it comes to poultry.

This has allowed the lobby to fight effectively on all aspects of regulation, including water protection (a particular problem for the Broiler Belt — home to an area of intense commercial chicken farming in the South-East of the US) and safety standards, which the four dominant corporations — Tyson, Sanderson Farms, Perdue and Pilgrim’s — remain committed to.

There is hardly any regulation on the breeding of chickens themselves aside from welfare standards set by the National Chicken Council, itself funded by the industry. These rules handily define the most cost-efficient methods as the industry standard.

In 2014, after one of the lobby’s long-sustained political fights, the industry won the right to replace official US Department of Agriculture (USDA) meat inspectors with staff on the company’s own payroll. It was exactly the kind of self-regulation food safety advocates had warned about for leaving consumers at risk of knowing less about what they buy.

The Southern Poverty Law Centre said more ‘tainted’ poultry would end up on America’s dinner plates as a result, rendering labels such as ‘humanely raised’ almost useless.

The US is barely coming to terms with the various effects of corporate consolidation which, as well as being a problem for consumers, also creates organisations who can battle government changes and drive down working conditions.

A 2016 study revealed that employees receive decreasing levels of pay as an industry becomes more concentrated. A second working paper in 2018 further demonstrated that pay was lower in areas where a small group of companies dominate the jobs market. These are often rural areas, where Trump garnered support.

This is a complete reversal of the social bargain reached in early 1970s America — the end of the public interest era when, according to McGarity, scholars believed the social bargain and role of business in society had been decided as‘what was good for American workers and consumers, not General Motors, was good for America.’

Today, what is good for industry profits, not workers or consumers, is seen as good business.

After doubling production over the last three decades alone, the spiralling decline of working conditions in the chicken industry are even more prominent.

This can be explained in part by the broiler industry’s unique contract-farming scheme, through which farmers are employed as ‘growers.’

Corporations own the chickens, the transportation networks and the feed mills. Farmers own the chicken houses and raise the flocks until they are ready to be taken away.

By 2011, 97% of production relied on contract-farming using broiler chickens.

But this structure is detrimental to farmers, who report being kept in debt to companies through a variety of techniques, including mandatory upgrades to equipment, reward structures which rank and punish farmers through payments, and other conditionalities.

Farmers can invest hundreds of thousands of pounds in chicken houses to ready their farms, and are sold the schemes on the basis of long term profits. Yet as the author of The Meat Racket, Christopher Leonard, explains, these schemes mean that farmers are kept in a ‘state of indebted servitude living like modern-day sharecroppers on the ragged edge of bankruptcy.’

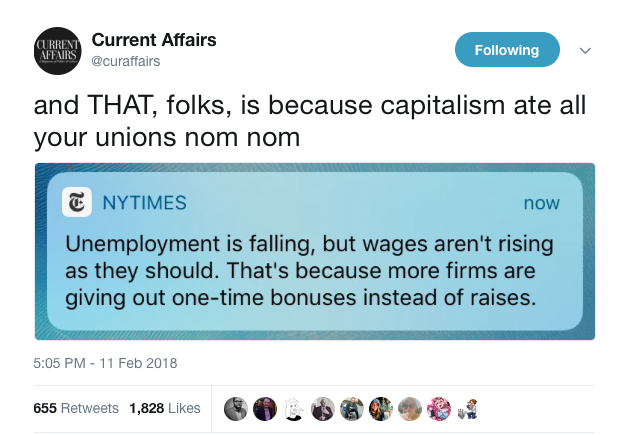

Upheaval of working contracts has been a supporting demand of the freedom movement, described as ‘labour market flexibility.’

It allows corporations to use workers more exploitatively, to hire and fire at will, translating to growing precarity for workers.

After successful neoliberal attacks on unions, workers are subdued further through these changes, receiving a decreasing portion of pay amidst record profits for corporations. In both the US and the UK this has resulted in falling unemployment, but stagnant wages and increasing in-work poverty.

Insecure contracts also gag farmers who fear punishment-through-the-paycheck for speaking out about their treatment. This is what historian Bryant Simon describes as‘strategic silences’ — an inherent element of deregulated industries in the service of cheap goods.

Silences mask the real costs of products which are extracted from elsewhere in the supply chain. This results in working conditions people have little choice but to accept, and environment pollution without accountability.

Simon examines the trap of cheap goods and deregulation in his new book The Hamlet Fire: The Tragic Story of Cheap Food, Cheap Government and Cheap Lives.

He discusses the case of the Imperial Foods Processing Plant in Hamlet, North Carolina — a factory where processed chicken meat was sent to be fried, battered and packaged.

On September 3 1991, a fire at the plant killed 25 people. The disaster came as a result of exploitative working conditions, deregulation and little oversight, all of which manager Emmet Roe had deliberately sought out.

In eleven years, the plant failed to receive a single safety inspection which could have prevented the fire. There were no sprinklers in the plant and Roe kept the fire doors locked to keep flies out and prevent staff stealing food, amongst a list of other safety rules he flouted.

Many of Roe’s employees were black single mothers who could not afford to lose their jobs, and they were treated as dispensible. Anyone who complained about fire safety was ignored.

When a hydraulic line failure started the fire on the Monday after Labor day in 1991, workers were left trapped inside the building. It would be one of the worst industrial disasters in recent US history.

Ceding to business demands for deregulation means ‘we’re letting businesses decide how our factories are run, the safety of our food and really the safety of our communities,’ Simon tells the Baltimore Sun:

‘We need to recognize the real cost of cheap, the real cost of deregulation. We need to break this cycle — this triumph of the system of cheap.’

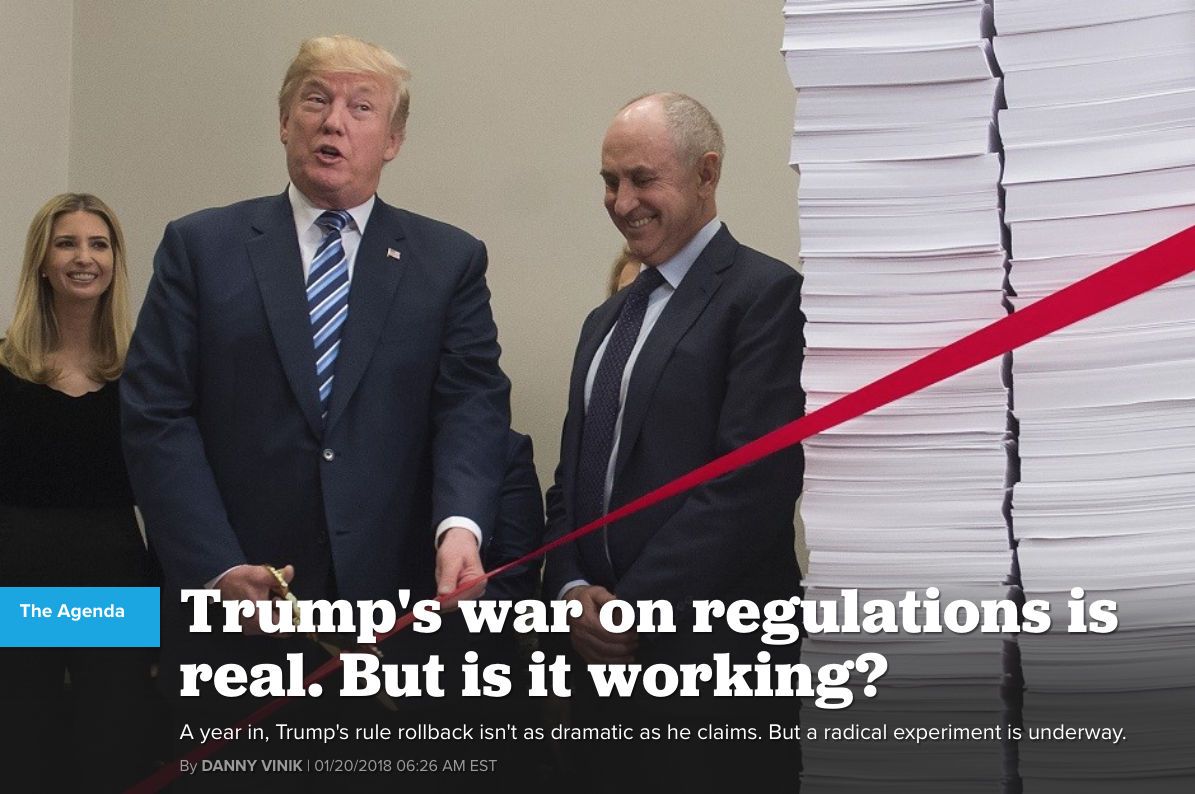

Simon’s plea comes as the Donald Trump administration is committing precisely to this dangerous system.

War on the public

Trump is fulfilling the wishes of the business community through his ‘war on regulation’, but the wishlists come thick and fast.

Already responsible for huge tax cuts (making organisations like Exxon Mobil and JP Morgan overnight beneficiaries), the removal of 67 environmental rules and a one in, two out policy (which sees two regulations removed for every one instated), the US administration is eagerly looking to unravel other forms of public protections.

Deregulation has many forms, and employs different methods to dismantle the public institutions concerned with recourse, oversight or consumer rights.

For example, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) — an Obama-era independent watchdog set up after the 2007–8 financial crisis to investigate market abuses — salvaged $12bn of consumer relief in nine years.

Trump brandished the CFPB a ‘total disaster’ which he promised to bring back to life. By that, he meant kill it from the inside. Trump did this by hiring Mick Mulvaney as CFPB head — a man who earlier co-sponsored a bill to eliminate the entire organisation. Mulvaney quickly changed the organisation’s mission statement, now listing its primary role as hunting down ‘outdated, unneccessary or unduly burdensome regulation.’ He also shelved action on predatory lending, data breaches and payday lenders.

Similarly, at the Consumer Products Safety Commission (CPSC), Trump elevated Ann Buerkle, who Pro Publica reports has ‘never in her fellow commissioners recollection, advocated for the agency to regulate a product the CPSC thinks is unsafe.’

One of Buerkle’s first moves was to sink legislation requiring portable generator manufacturers to reduce carbon monoxide emissions, a problem known to kill 70 people and poison 2,800 a year in the US.

The chicken lobby also wants in on the new deregulation frenzy, demanding the removal of ‘arbitrary’ line speed limits in chicken slaughter houses.

The current limit of 140 birds per minute, put in place by the previous administration, was already a token safety measure. The poultry industry, however, wants to work at any speed deemed safe to ‘compete in the global marketplace’(i.e. produce goods more cheaply), insisting that safe working practices have improved and will not be harmed.

Labour groups and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) say different.

In the low wage factories that make up the industry, there are widespread concerns that workers, many of whom are immigrants and refugees, do not report injuries for fear of losing their jobs.

In 2016, the GAO investigated the industry’s ‘under-reporting problem’, concluding they were not getting the full picture from federal data.

Slaughterhouse workers are already susceptible to danger in an environment of bacteria and sharp tools. Rates of injury are higher for these factory workers, yet the GAO found some were punished for frequent health visits.

Debbie Burkowitz from the National Employment Law Project, said there was ‘no data to support that [abandoning line speed limits] would be safe.’

Other methods of deregulation by the back door include limiting resources. The film ‘Under Contract’ looks at contract-farming and cites the deliberate underfunding of the USDA — charged with the protection of farmers — as a reason for prolonged violations.

While Trump’s plans have been met with anger, almost identical policies have been carried out in the UK with less furore.

Since 2008, UK policies have led a race to the bottom for working conditions, deregulation and cheap goods, demonstrating the dominance of freedom movement ideology. The UK has also seen huge corporate tax cuts, successive deregulation bills and an increase from a ‘one in, two out’ policy, to ‘one in, three out.’

(Cato Institute — another US Atlas Network member, discussed ‘Lessons from the UK’ in regards to this policy last year. Cato were named as one of the participants in recent ‘shadow trade talks’)

In 2015, former banker turned UK Communities Secretary Sajid Javid beamed to businesses that the UK had cut £10bn of red tape between 2010–2015, becoming the ‘first government in recent history to reduce overall levels of regulation’, with the ‘lowest burden’ in the G7.

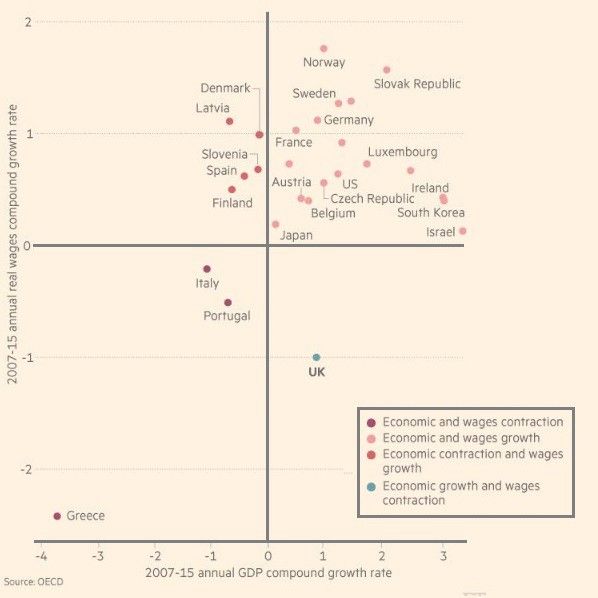

This has tallied with wage contraction despite economic growth — just like the US chicken industry. Deregulation under Brexit will come on top of an already raided rulebook.

Two years later the same Communities Secretary would be issuing assurances to the residents of UK tower blocks, after the Grenfell Tower fire on June 14 2017.

Cheap flammable cladding used in a renovation the previous year caused the fire to spread and kill at least 71 people in a Central London borough.

Like the Hamlet Fire, safety inspections could have found faults but were cancelled due to fire service cuts. Sprinklers were not a part of the renovation and the government sat on a report regarding action on tower block conditions. Residents who raised concerns at Grenfell Tower were threatened with legal action.

Deeming these events unpredictable breeds further unaccountability in a faceless system. In previous eras, regulation was used to prevent tragedies repeating, but the UK government has failed to act by replacing cladding at other towers.

By December 2017, ‘not a single penny’ had been set aside to deal with the issue. Further, a report by Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth found that a government-backed cross-party group called the Red Tape Initiative had met to discuss what regulation could be removed under Brexit in regards to fire safety, on the very morning of the fire. The group is led by Oliver Letwin, who authored some of the deregulation bills passed in recent years.

Business as usual returned quicker than ever.

Special Relationships

Like Liam Fox, the UK’s International Trade Secretary, Daniel Hannan has made frequent visits to the Heritage Foundation over recent years.

Hannan and Fox are also connected to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), funded by the billionaire Koch Brothers, Exxon Mobil, Pfizer, private prison companies and any organisation willing to pay the thousands of dollars of membership fees.

The group boasts of submitting one thousand new legislations each year with 20% becoming law. Harsher sentencing, lowering minimum wage, fighting environmental laws and (perhaps unsurprisingly) rules dubbed ‘ag-gag laws’ which prevent people from investigating factory farming practices, are some of ALEC’s recommendations.

ALEC is a group that changes the shape of US governance daily, in the interests of its donors.

Hannan’s declaration of MEP financial interests in 2009 revealed that ALEC paid for some of his US flights. Liam Fox’s own organisation, Atlantic Bridge, was in partnership with ALEC before being shut down after an investigation by the charity commission.

(Jamie Doward reported in 2011 for the Guardian that ‘a typical theme’ of one Atlantic Bridge conference was ‘Killing the Golden Goose — How Regulation and Legislation are Damaging Wealth Creation. Another was called ‘How Much Health Care Can We Afford?’)

Margaret Thatcher was a patron of Fox’s think tank and the board included William Hague, Michael Gove and George Osborne.

Corporate coziness forced Liam Fox to resign as Defence Secretary in 2011, but those same connections made him indispensible in November 2016, after the election of Donald Trump. With Fox and Hannan at the centre of the movement, they celebrated in true Atlas Network style — the launch of a new think tank.

In September, Boris Johnson used a government building to inaugurate the Initiative for Free Trade — an organisation led by Daniel Hannan, and granted an opening speech by Liam Fox.

Fox’s relationship with the US hard-right will see him define our negotiations. In one of their first meetings, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross was adamant that the UK must concede on food standards.

This is a second chance for Big Agriculture — one of the most aggressive forces in the now-dormant Trans Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) deal — which sought mass deregulation and secret courts to account for lost corporate profits, as well as the freedom of its goods across the EU.

And they don’t come much bigger than the world’s new agrichemical giants who have already started their assault on public opinion and legislation in the UK.

Hello Monsanto

Hannan’s toast rested on one underpinning of regulation in particular, whose loss would signal a complete upheaval of UK agriculture. This underpinning is responsible for the chasm between US and UK food standards, and regarded by many as the foundation of all regulatory protection for environment and food safety — the Precautionary Principle.

With increasing use of technology and chemical enhancement across industries, the risk factor rises. The precautionary principle reverses the burden of proof when the danger is high, so that a product must be proven to be safe beyond reasonable doubt. But precaution is exactly the kind of word the freedom movement has worked to malign, and now they want to put an emphasis on ‘innovation above caution.’ This would result in the reversal of the Precautionary Principle, to the US approach — where the danger must be proved before a product is banned.

The opportunity has pricked the ears of, among others, American seed giant Monsanto. The Times reported the company was eyeing up the opportunity to grow Genetically Modified (GM) crops in Britain after Brexit.

Until now, Monsanto has had a relatively small presence in the UK, and GM food has taken a backseat to headlines about chlorinated chicken. But the emergence of GM would constitute some of the biggest changes we could see when it comes to food.

Just when the UK may be introduced to such products, the industry is undergoing unprecedented corporate consolidation, with a handful of companies wielding global power over the future of food.

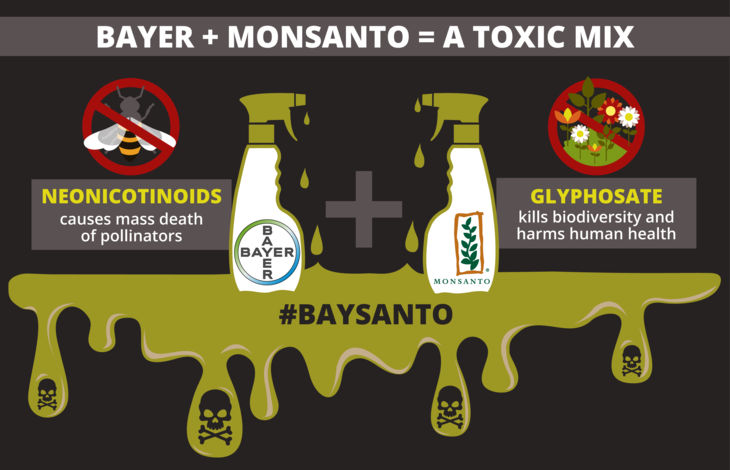

Following mergers between Dow and DuPont, and Syngenta and ChemChina, German giant Bayer is hoping to close a $63bn deal with Monsanto as soon as possible — reducing the world’s six agrichemical giants to just three, between them controlling 60% of the world’s seed and pesticide market.

Yes US farmers are worried. The mergers leave them with less choice, less competition and no options to escape increasing prices.

The giants say the mergers mean more innovation, but farmers are unconvinced and feel trapped. Dee Vaughn, Chairman of the Texas Corn Producers Issues Committee told Texas Tribune:

‘We have to buy seeds; They have us in a situation where we have to buy their produce. But they still have the ability to go even higher on their prices.’

So much for choice.

Bayer and Monsanto were hoping to have the deal wrapped up by the end of 2017, but anti trust investigations and legal battles have stalled progress. The EU is expected to return the decision of its review on March 12.

Monsanto’s farming technology largely involves producing higher yields and enhanced seeds. For example, a weedkiller containing the chemical dicamba can be sold with accompanying resistant seeds, allowing farmers to kill weeds without harming crops. Sales of dicamba rose after weeds became increasingly resistant to the previous RoundUP product.

This has created a whole new agricultural crisis in the US today, which demonstrates the advanced risks of new technology and corporate dominance.

Dicamba is susceptible to drift, which means it can form vapour clouds which spread onto neighbouring fields, where crops are at risk if they are not resistant to the product.

Over the last 18 months, 3.6 million acres of the US farm belt suffered from dicamba drift after a spike in sales, resulting in the investigation of 1,400 complaints across 17 states.

It has created deep tension amongst farmers who have no recourse and are not insured for dicamba drift. In 2016, an Arkansas Sheriff confirmed a farmer fatally shot a neighbour due to a dispute over the chemical. Another Arkansas Farmer, Nathan Reed, whose crop was damaged by dicamba use two miles away, said it ‘put using non-GMOs [Genetically Modified Organisms] at risk.’

To counter the backlash, Monsanto began offering a cash incentive to farmers to use the controversial dicamba products even as regulators were starting to weigh in on how to approach the issue and the chemical was causing a new emergency across the US.

Dangers come not only from damaging technology, but corporations who fight to continue using it, just to maintain industry domination.

Could this really be a part of Monsanto’s business strategy? Kyle Steigart, Professor of Agricultural & Applied Economics at University of Wisconsin believes so. Responding to the incident, Steigart explained:

‘Monsanto has been an aggressive business entity in dominating the industry for some time now. I would see the dicamba situation as just another step in that direction.’

Nevertheless, the ground is being prepared and public opinion shaped. Last week, Open Democracy reported that SynGenta had signed a major commercial deal with ESI Media through which the chemical giant ran a series of public ‘debates’ and articles on the ‘future of food’ through London’s free paper — The Evening Standard, edited by ex-Chancellor George Osborne.

Billion dollar legal challenges, orchestrated attacks on scientists by the company and controversy over the prospect of GM foods in the UK were all omitted from the coverage — all part of a ‘growing practice inside ESI Media which deliberately blurs the line between advertising and editorial content,’ Open Democracy found.

Syngenta and Monsanto are among the companies currently engaged in intensive lobbying during Brexit.

The merits and demerits of GMO products deserve rigorous public debate, but GMO companies have long battled to prevent consumers from knowing what they are buying.

‘GMOs were introduced in the US with no warnings whatsoever’ explains Helena Paul, Co-Founder of Eco-Nexus.

In 2015, the food industry spent more than $100m in the US on GMO-related issues to prevent mandatory labelling and state-by-state approaches to regulation after Vermont intended to make changes to inform consumers. President Barack Obama failed to introduce labelling for GMOs despite making a campaign promise. Now, food companies complain that labelling would create ‘stigma’ about foods which are, supposedly, scientifically safe.

But how can we have the choice Daniel Hannan speaks of if we don’t know what we are eating?

The Atlas Network is a global pusher of corporate interests, and some of its well-placed main players are engaging in a coup against public rights and protections during the Brexit transition.

Hard Brexiteers will sell us narratives of cheap products and consumer choice, but it comes with hidden costs and the choices are not what they seem. What we won’t hear is promises of better living standards, higher wages, healthier lives or stronger rights, because this rhetoric hides a continued race to the bottom.

This is a strategic silence that must be broken.

Thanks to Nafeez Ahmed.