In this sobering exclusive analysis for INSURGE, Professor Ugo Bardi dissects historical statistics on war to unpick the patterns of violence of the past, and uncover what this says about the present — and our coming future.

He warns that statistical data suggests we are on the brink of heading into another round of major wars resulting, potentially, in mass deaths on a scale that could rival what we have seen in the early 20th century.

Far from mere doom-mongering, Bardi’s warning is based on a careful assessment of statistical patterns in the data.

Such a future, however, may not be set in stone — given that for the first time we are able to assess our past to discern these patterns, in a way we could not do before. Perhaps, then, the path to freedom from the patterns of the past remains open. The question is: what are we going to do with this information?

Humans are dangerous creatures; this much is clear. During the 20th century, about one billion humans were killed, directly or indirectly, by other humans.

Not all these murders were intentional, but a good fraction was, including some 262 million people killed in what Rummel calls “democides”, the government-organized extermination of large number of people for political, racial, or generally sectarian.

If we add the number of people murdered piecemeal (maybe 177 million during the 20th century), the total is nearly half a billion people killed in anger by other people.

Considering that about 5 billion people died during the 20th century, we can say that during that century the probability of dying killed by another person was about 10%. Not bad for creatures who claim to have been created in the image of a benevolent God.

No other vertebrate on Earth can do anything even remotely comparable, even though chimps and other apes may be cruel with their kin and occasionally engage in skirmishes which we could define as small-scale wars.

Today, by comparison with the turbulent mid-20th century, we appear to be living in a relatively quiet period and it has been argued by Steven Pinker that our times are especially quiet in comparison to the past (though exactly how quiet remains a matter of debate). But there is a big question: for how long will the lull last?

It is, of course, a very difficult question, to say the least. Nevertheless, a good way to be prepared for the future is to look at past trends. In the case of mass exterminations, the historical data is scarce and unreliable, but we do have some. The Conflict Catalog (here) is authored by Peter Brecke and contains information on 3,708 conflicts, going back to the 15th century. It is a good place to start.

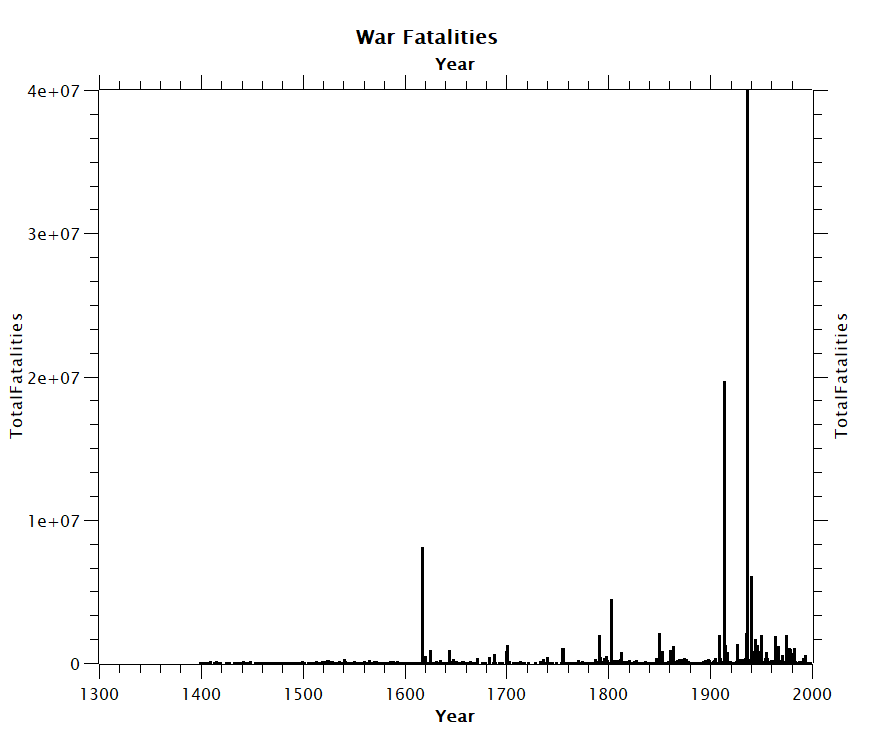

The “War Fatalities” data in the Conflict Catalog includes both civilian and military victims, even though they don’t seem to include those mass exterminations that didn’t involve military operations — for instance the extermination of the Native Americans in North America. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating set of data. Here is the plot.

You see that the graph is dominated by 20th century wars, with the Second World War marking the historical maximum. It doesn’t mean that earlier times were quieter: let’s zoom into the data by plotting them on a scale that expands the data bars by a factor of 10.

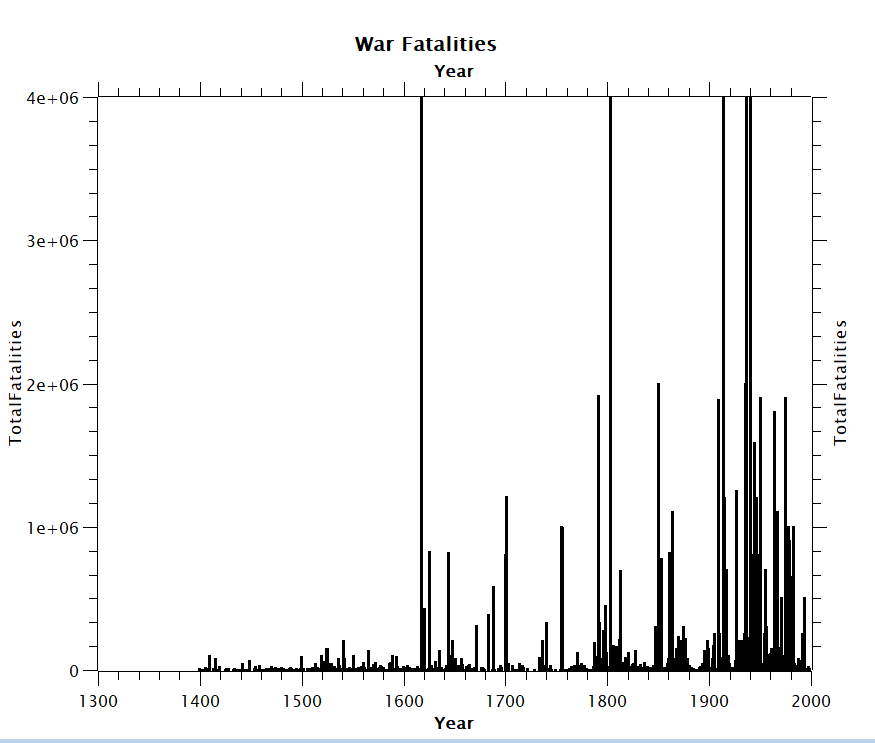

Now, you see better the bursts of war in the past, including the Thirty Years War during the early and mid1600s, as well as the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars during the late 1700s and early 1800s.

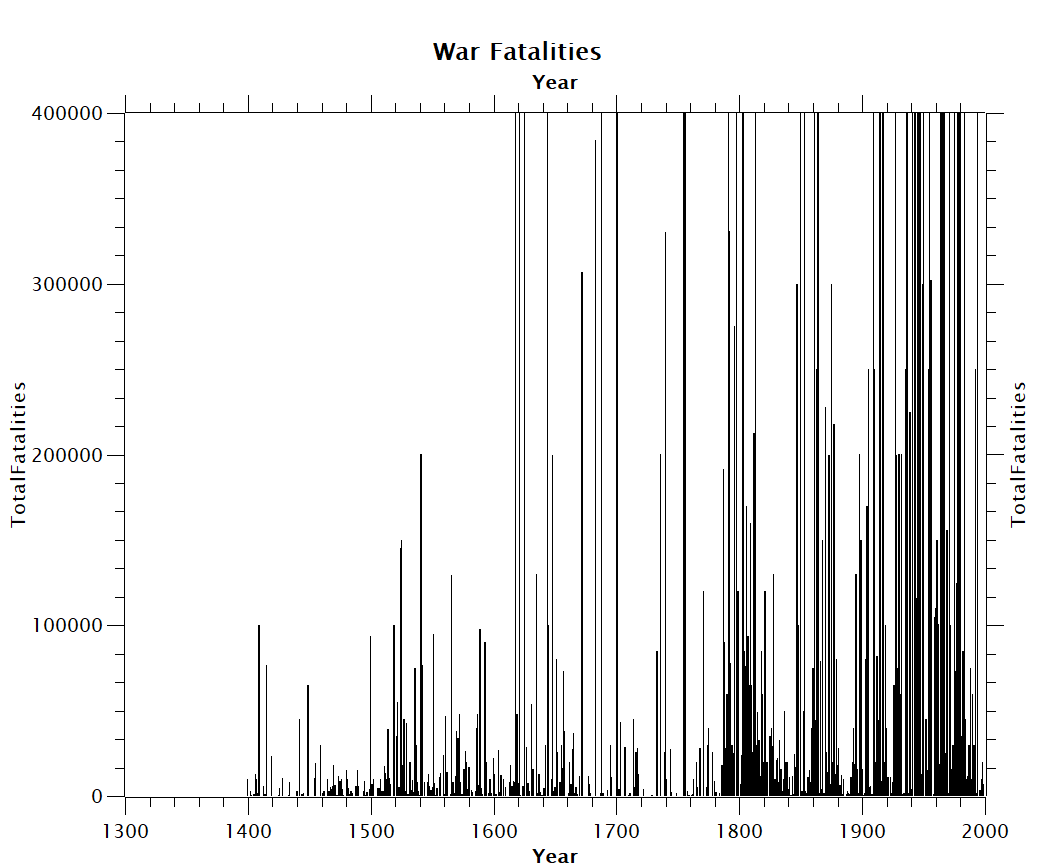

Now, let’s zoom in by another factor of 10, and see the result:

Now, the periods that looked quiet don’t seem to be so quiet, after all. War seems to be endemic (and sometimes epidemic) in human history, at least during the past six centuries.

So what can we say about this data?

A first point is the apparent increase in intensity with time. But the data are not corrected for population growth, which seems to be a key factor explaining the increasing trend.

For instance, the worldwide democide pulse of the 20th century generated 260 million victims for a world population of about 2.5 billion people. The Thirty Years War in Europe, during the 17th century, caused some 8 million victims in the European population which, at the time, was 80 million people. The ratio is nearly the same in both cases: about one person in 10 was killed. It seems that the intensity and the rate of major conflict pulses is approximately constant in proportion to population.

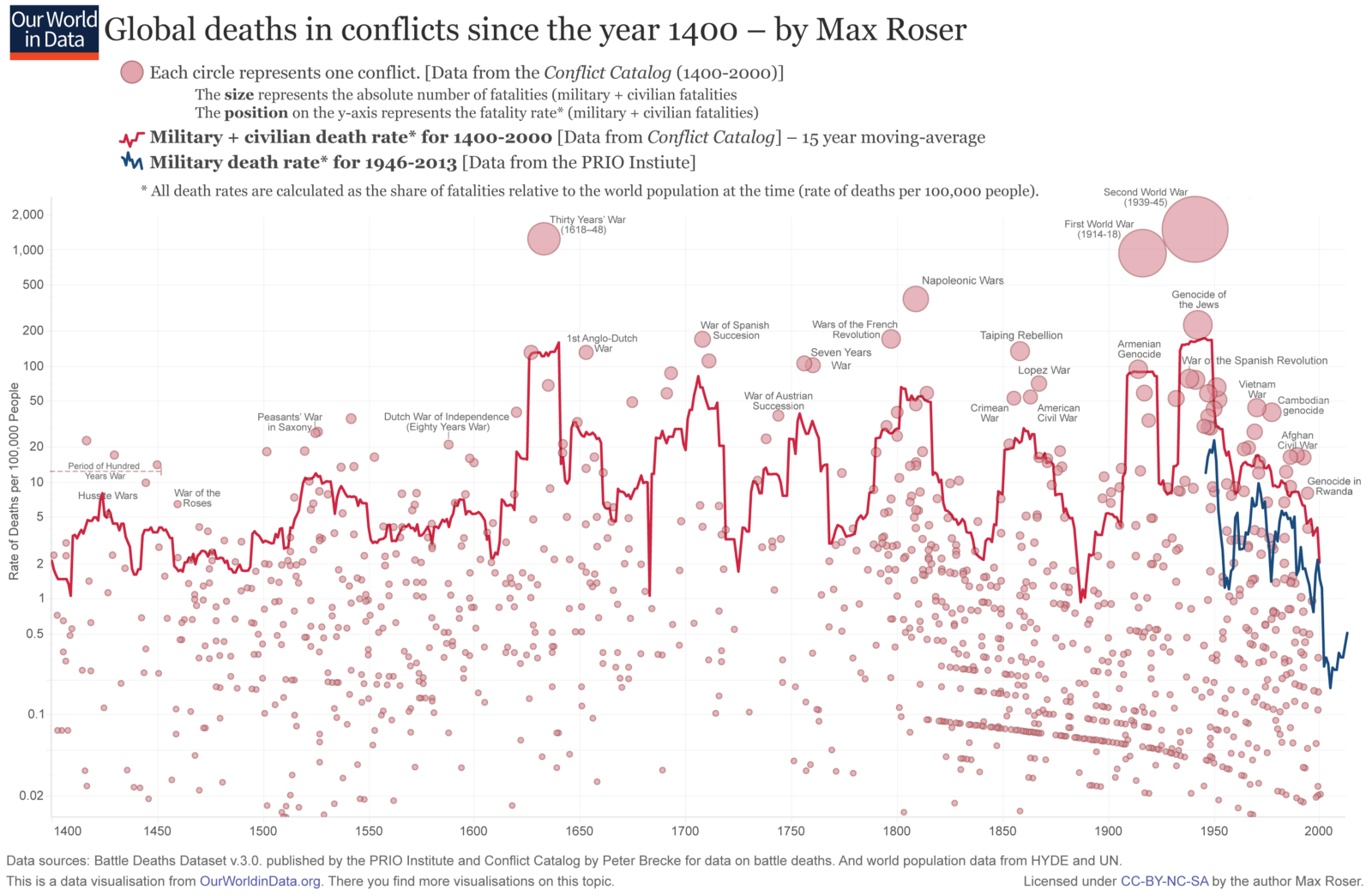

Do we see any evidence, then, of periodicity of the data? Apparently not in the plots above. But we could try to smooth the curve by averaging. Here are the results in a plot made by “OurWorldInData.” This data is the same that I plotted before, but on a logarithmic scale. The data has also been smoothed and the result is the red line.

At first glance, this graph seems to indicate a periodicity of about 50 years, but that may not be true. Look carefully: the cycles are not all of the same duration.

So, the oscillations are probably mostly an artifact of the smoothing. In reality, mass exterminations don’t seem to be cyclical. Rather, they seem to follow a “power law” — that is their probability is inversely proportional to their size (Roberts and Turcotte (1998) and Gonzalez-Val Rafael (2014)).

It is a result that we have to take with caution because the data is uncertain and scarcely reliable, especially over long time spans. But it seems reasonable: it puts wars in the same category of forest fires, avalanches, landslides, earthquakes, and more.

All these events have a common characteristic: large events are triggered by small ones. A rolling pebble may generate a landslide while an abandoned lit cigarette may generate a forest fire. It is the same for wars, where the tendency of small wars to generate large ones is called “escalation.”

All these events tend to follow “power laws.” It means that large wars are less probable than small ones. But we can’t say when a new war will start, nor how big it will be. It is the same for earthquakes. It is this uncertainty that makes earthquakes (and wars) so destructive and so difficult to manage.

This is worrisome, to say the least. It means that, statistically, a new pulse of exterminations could start at any moment and, the more time passes, the more likely it is that it will start. Indeed, if we study even just a little the events that led to the 20th century democide that we call the Second World War, you can see that we are moving exactly along the same lines.

We are seeing the rise of hate, violence, racism, fascism, dictatorships, rising inequality, sectarian ideologies, ethnic cleansing, oppression, and the demonization of various modern “untermenschen” (sub-humans). All this can be seen as the precursor for a new, large war engagement to come.

We are already seeing an arc of democides that starts in North Africa and continues along the Middle East, all the way to Afghanistan and which may soon extend to Korea. We can’t say if these relatively limited democides will coalesce into a much larger one, but they may become the trigger that generates a new gigantic pulse of mass exterminations.

If the proportionality of democide size with population size holds, we should take into account that, today, there are three times more people in the world than there were at the time of the Second World War. The resulting 21st century democide could therefore involve anything between half a billion and a billion victims, or even more; especially considering that, this time, nuclear weapons could be used on a large scale.

Can we do something to avoid this outcome? According to Rudolph Rummel (1932–2014), who studied wars all of his life, democracies are much less likely than dictatorships to engage in wars. In this interpretation, promoting democracy could be a good way to avoid wars.

This is debatable: We might question the extent to which Western democracies have really refrained from engagement in wars. Or we might say that a healthy democracy is an emergent property of a sane society just as war is an emergent property of a sick one.

So when a society gets sick, impoverished, divided, and violent, it gets rid of democracy and engages in war. It seems to be exactly what’s happening to us nowadays: we are weakening and jettisoning democracy, and gearing up for a new, large pulse of mass exterminations.

The past 50 years or so of relative calm, at least between Western states, may have deluded us into believing that we have entered a new era of ‘long peace’. But that may have been just an illusion if we look at the continuous eruptions of warfare of the past half millennium. Wars seem to be too inextricably linked to human nature for it to be stoppable with mere slogans and goodwill. Theoretically, everyone is against war but when flags start waving, reason seems to fly away with the wind.

Yet, there is more to be said on these trends. It is often said that all wars are for resources, but this may not be true. Wars need resources. You could say that resources generate wars, rather than the opposite. So, the great cycle of growing democides of the past half-millennium has taken place against a background of increasing population and wealth accumulation. That made it possible to build and maintain the social and military apparatus needed to make wars.

But now? Clearly, we are seeing the start of a phase of dwindling resource availability. Mineral resources are becoming more expensive, arable land is being rapidly depleted of nutrients, the atmosphere is being poisoned and climate is rapidly changing in ways that are going to harm humankind to levels which, at present, we can’t even imagine. There is less and less surplus to be invested in wars.

Of course, there are still plenty of reasons to go to war against each other; in particular to take control of the remaining resources. And it is also true that democides don’t need to be expensive; some recent democides such as the one which took place in Rwanda in 1994 did not require more sophisticated weapons than machetes. Then, it may be even easier to engineer a democide by denying low cost medical assistance to the poor.

Yet, there remain great uncertainties as we are rolling over to the other side of the great cycle of what we call the “industrial civilization” that spanned several centuries.

While wars and exterminations were a common feature of the growing phase of the cycle, will they also be in the declining phase? We can’t say. What the future will bring to us, only the future will tell.

But for the first time in human history we are able to look back at the past with a birds-eye view that can inform us of the patterns of behaviour we are bringing into that future — thus, for the first time, perhaps, we can collectively learn from the lessons of our past to create a future with somewhat different patterns.