ABSTRACT /// In this essay and partial analysis of our current economic paradigm(s), three precepts are established:

- Amazon’s relatively swift albeit vulnerable domination of retail commerce through a quick delivery infrastructure, the crucial missing elements, and what this really entails economically;

- How that infrastructure is actually primed to enable exponential smaller market growth & why this translates into substantial ecological stability (which will ultimately benefit more and more people, as well as the planet);

- How this is forcing businesses in every single industry, at a wildly accelerating rate, to adapt or die, and what businesses ‘on the fence’ can actually do about it (or not, depending on how stubborn and idealistic they really are).

In establishing these precepts, a framework is then offered from which to envision multiple futures, futures that vary in their composition, social structures and ecological relevance. And which, overall, exhibit deeply diverse, polycultural traits.

The goal here is to lay out the transition between the current paradigm and a new paradigm by identifying some unseen realities, connecting some commonly misunderstood elements, and enabling you, the reader, to generate your own insights as to what you see being possible. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to do this. Just as no one can really predict or control ‘the future’, this is merely a means to conduct an interpretive exploration.

That said, there are many overriding narratives + belief systems that tend to lock people into ‘one version’ of the future, which can effectively replace one monoculture with another, from ‘transhumanism’ to ‘neural networks’ to ‘intentional communities’ and the like. ‘Economy’ narratives such as ‘the sharing economy’ or ‘the data economy’ or ‘the gig economy’ or ‘the platform economy’ also tend to paint very narrow pictures of what’s possible, even if they invite in more and more ideas for innovation.

In a polycultural world, all possibilities co-exist. As well, many realities will evolve that reveal to us the expansiveness, abundance and creativity that has yet to be unlocked within humanity’s potential.

As the wise mythical writer June O’Brien teaches us:

“I will care for my consciousness with the tenderness of a good mother. Or father. With the knowledge that I have been given the reality I asked for, and it is to this I owe my allegiance.”

For now, this isn’t about Amazon versus the rest of world, but what the worlds of business and civics are doing, and will do, with Amazonian Economics embedded within them.

See you on the other side.

Our exploration actually begins with Henry Ford

There’s a little-known story about the famous automaker when he decided to expand his company’s marketshare.

The popular story has been the one in which Ford made his cars so affordable that his own employees could buy them, thus creating a viable, somewhat revenue-sustainable market amid downturns and distending recessionary effects.

That’s a neat story, no doubt.

But the story we want to employ for the purposes of this exploration — what emerges as a modern-day allegory — is the one in which Ford had to make a series of hard choices, one in particular between creating extended markets on more consensual terms, or controlling the one he had already made strictly on his own terms. This is the story about an industrial oligarch, who along with the likes of Henry Flagler and the Rockefellers, had choices involving a certain kind of power and the ability to mold society in monocultural ways.

What actually happened was, and still is, rather ironic.

The story is simple: Ford was a devout fascist, a surprisingly ill-informed anti-semite, who deferred to perverted, derivative texts such as the “The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion” for societal ire and classist enrichment.

As of 1919, Ford had been connecting with other industrial oligarchs in Germany and ended up building much of what became the Third Reich’s transportation infrastructure — military vehicles, tanks, what have you. This effort lasted through the Weimar Republic days, through Germany’s new parliamentary restructuring, the formation of its nationalistic labor party, nearly all the way through to the end of the war in 1945.

Eventually, Ford got his hand slapped by American congressmen and select lobbyists for ‘doing business with the other side’. Had it not been an overt geopolitical conflict of interest, Ford’s internationalist tendencies may have gone unchecked.

That, of course, didn’t stop him from employing the services of German (Nazi) engineers to work on his automobiles, nor did it stop him from influencing the selections of German (Nazi) scientists during the formation of the Central Intelligence Agency in 1947, under Project Paperclip.

As those details are unfortunately true and fairly well documented, Ford, by his own admission, also led a sad life. He was inevitably stung by his own business and political decisions, became further and further disenfranchised from the company he founded, and longed to return to a pastoral life until his death. Thankfully along the way, his sons were able to relieve him of his kleptocratic inclinations, allowing the company to flourish for decades.

The ‘moral’ of the story?

It can be a very fine line between commercial interests, societal intentions, and preconceived notions of economic prosperity.

In this story, we see all the characteristics of industrial arc and archetype:

A choice around power.

Choices on how to build markets.

Choices regarding sociocultural impacts.

Personal impacts.

Gateways for change.

In today’s world, the very fine line is even finer. Industries are deeply interlinked, and economic elements are extremely interdependent. As are the people who have the economic power to make sweeping decisions, practically on the fly.

One such person is Jeff Bezos.

Jeff Bezos is not a fascist, as far as society can tell.

He certainly could be deemed a technogarch (if there is such a word), by all appearances and market actions.

More glorified comparisons of Jeff Bezos to Henry Ford have been made over the years, particularly with respect to worker welfare. But as we’ll see in short order, this is really no longer about labor and production efficiencies, and really about the ways in which production and distribution change when the very markets both Bezos and Ford have revered as their ‘opportunity funnels’ no longer operate on their terms, nor on the terms of their majority shareholders.

As a somewhat enigmatic public figure, Bezos is relatively mum on geopolitical and economic issues, despite owning mainstream media outlets like The Washington Post, and despite having a significant stake in all five of the top Internet companies, as well as stakes in the major media conglomerates. Rumors have circulated for a few years about Amazon’s large $600m contract with the CIA (a robust data system — surprise, surprise) and nefarious agendas protecting the surveillance apparatus, as it were. But as of now, most if not all of these rumors are relatively unsubstantiated.

With a certain kind of steely resolve, Bezos has built an empire like no other.

Amazon is now the most valued company in the world according to market pundits, and founder, CEO and modern-day statesman Bezos is officially the second richest man on earth.

To clear, when it is written that Amazon is ‘the most valued by market pundits’, this does not mean that it has the highest market capitalization (as of this writing, Apple, Google and Microsoft all have higher market caps), it means that it has the most perceived value by a number of analysts in terms of its combination of assets, operations, scale, footprint as well as market cap. And for many reasons described in this essay, it may very well be the case. As for a deeper market analysis, its innovation efforts are probably the best barometer of its trajectory towards complete online retail domination.

What's amazing about Amazon is that it looks like a holding company, but instead of just owning assets (real estate and technology mostly), it catalyzes significant, innovative movement in just about every category of business you can imagine. Amazon is highly active in every major vertical and ‘subvertical’, from cloud computing, to ‘big data’ and AI, to logistics, governance, education, energy, media, healthcare, and more recently, food.

As of June 16, 2017, Amazon has acquired Whole Foods.

And here’s a question you might be asking: What does it all mean for the (future) economy?

Perhaps one even more burning: What exactly is the world that Jeff Bezos sees us living in?

Sound Economic Rationale

Well, to begin answering these questions, we’ll need to look at three axioms that are driving our current economic realities.

Here’s the first:

Axiom 1 ::: New assets and asset classes in the form of resources + utilities — natural, intellectual, civic, etc. — are needed to ‘restart’ as well as stabilize the economy.

For further clarity, an asset is a resource that can generate revenue such as a piece of real estate, or a crop, or a technology, or a fuel; an asset class is a set of assets through which resources are developed as utilities that people can use to live and work; utilities can be anything from a food subsidy, to a civic voting app, a transportation system, or an energy grid.

Here’s the second:

Axiom 2 ::: Markets are more pliable, and therefore more unpredictable, than ever before.

And the third:

Axiom 3 ::: Cash and credit are completely changing face.

So we have three main elements at play, which are interrelated and interchangeable: Resources, markets and payment systems.

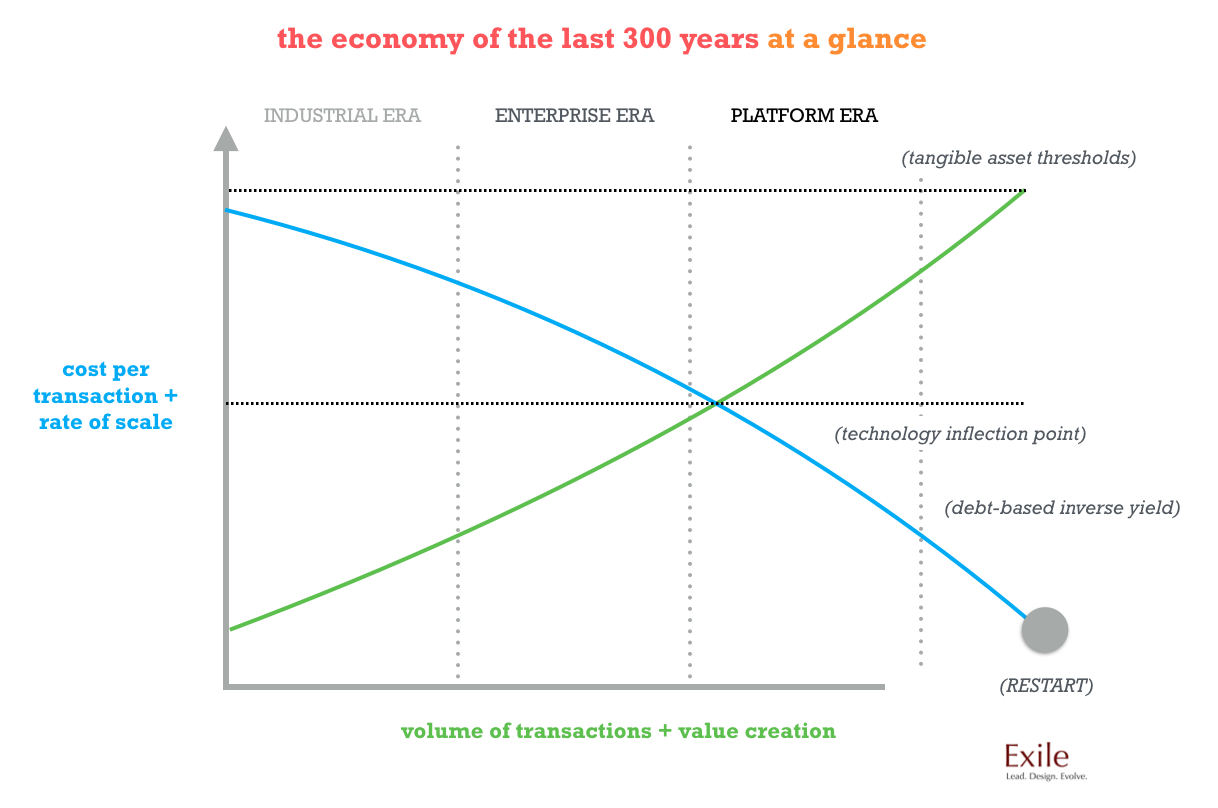

Here we can also begin to think about the naunced relationship between resources, markets, and payment systems and the associative behaviors that actually affect economic outcomes. More specifically, we can see how the economy of the last three hundred years has reached a technology inflection point. This inflection point represents the gap between tangible asset thresholds tied to the volume of transactions + value creation and debt vehicles tied to each transaction + rate of scale.

What this shows us is that unlimited vertical scale or growth is a complete fallacy, and that bubbles are not only inevitable, but are accelerating at a compounded rate. From a macroeconomic standpoint, this means that we must restart the ways in which we produce, distribute and consume through multiple baselines which use thresholds to manage asset imbalances and liabilities such as sovereign debt (what countries owe their central banks).

On a microeconomic level, imagine how this would impact your own neighborhood or local environment — what are the things you see missing or are needed for you to live and work better, and to do so on your own terms?

Let’s take our next logical steps.

Relevant Economic Data

Spending, production and consumption are drastically shifting.

Lots of government census data (in the U.S.) reveals relatively little about our actual employment and underemployment situation. Productivity rates and labor participation are easily identifiable indicators of real economic growth. At a microeconomic level, they affect spending, among many other things, to include production and consumption rates.

Analysts speculate that in the U.S. unemployment rates are closer to 9% as of this writing, and that underemployment rates hover between 13% and 15%. Let’s assume these figures are somewhat accurate, for no other reason than the other data we can scrutinize will tell a much more dramatic tale.

Economists often rely on the labor force participation rate, which measures the portion of the population that’s either employed or looking for work as a key indicator for ‘prosperity’. The participation rate has fallen significantly since its high around the year 2000, most likely due to demographic shifts such baby boomers retiring, as well as higher birth rates and two new generations of ‘non-working’ citizens. But those demographic shifts don’t account for all of the change, which has led some economists to think it has more to do with fundamental shifts in the economy. In this sense, they’re right, but not necessarily for the reasons they cite or those they might think.

So let’s shift our focus on the three data-points that really do matter:

- We’re coming on the 11th straight year without 3% growth in GDP.

- Retail inventory (real estate — storefronts, malls, etc.) is experiencing turnover above 70%.

- The majority of retail spending is with cash, while the majority of asset purchases (cars and houses) are made with credit (debt).

As any institutional analyst might attest to, real wealth and spending power are reflected in housing/real estate, specifically home or property ownership. Leasing and tenancy are also signs of shifts in gainful employment and discretionary income, not to mention the leverage utility businesses (energy companies, warehousing businesses, transportation entities et al) have in the market — the self-storage industry is a great example. Basically, these businesses are cash flow-intensive, quick turnaround operations with little overhead, which is very attractive to investors in terms of IRR (internal rates of return) as well as cash-on-cash growth (the returns an asset provides in the form of active or passive income).

The more somber reality: We are already experiencing auto and home loan bubbles. Basically, this means that mortgage and other loan vehicles are unable to recall the cash on those loans. (Seems familiar, doesn’t it?). The caveat, of course, is that the bubbles are highly selective — with low rates and higher income class mobility, people are still buying homes and cars, it’s just that those purchases exist in tighter pockets.

What a stagnant GDP figure tells us is that cash flow (a.k.a. free capital or liquidity) is not offsetting debt and overconsumption. Which also means that productivity levels are in overall decline, and despite increases in service wages, labor or manufacturing, wages overall are in decline as well. This might be obvious, except for the fact that people are still spending money, which also means that in most cases, they are spending whatever disposable income they have and/or their savings.

From a resource and asset perspective, this means we are wasting precious materials on things that people can’t actually afford given their living standards.

So, the real story here is that we are in a strong recessionary decline, and we haven’t even addressed the roles that monetary policy and bond inversion play in this scenario.

So again, the net-net: spending, production and consumption are drastically shifting.

But don’t despair, this is ultimately a good thing.

Now… Back to Amazon

Amazon is in the quick delivery business.

Yes, it’s described as an online retailer, but what it actually does is it uses technology to optimize the speed at which products and services (and service products) are delivered to people. It’s a service utility company with a lot of products that create a lot of market value.

For example, Amazon has an end-to-end system that can provide you with energy, storage, clothing and/or food, deliver it within a very short window, and in the process provide you with relevant data and product upsells, all without advertising if it wants (sidenote: Amazon’s digital advertising revenue of $1.2b is second only to Twitter’s). It’s the reason why the company’s stock price is so high, and why, on a cash + margin basis, the company is able to reinvest in other businesses and industries more or less at a dollar-per-dollar ratio.

In fact, Bezos has been doing this since the company’s inception, much to the dismay of impatient shareholders. In fairness to the shareholders, it’s historically difficult to prop up share value with negative or flat EBITDA (for those unfamiliar: earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization). In fairness to Bezos, this is precisely how you move a company beyond speculative value into long-term, accruable value— you build up your own asset base and corner the market. In Amazon’s case, it’s cornering virtually every market.

Good for Amazon. And surprisingly, good for the rest of us.

(Let’s keep going…)

Why the ‘Middle Market’ Matters

Now we have to consider the implications of having this capability in a ‘down’ market or a recessionary economy.

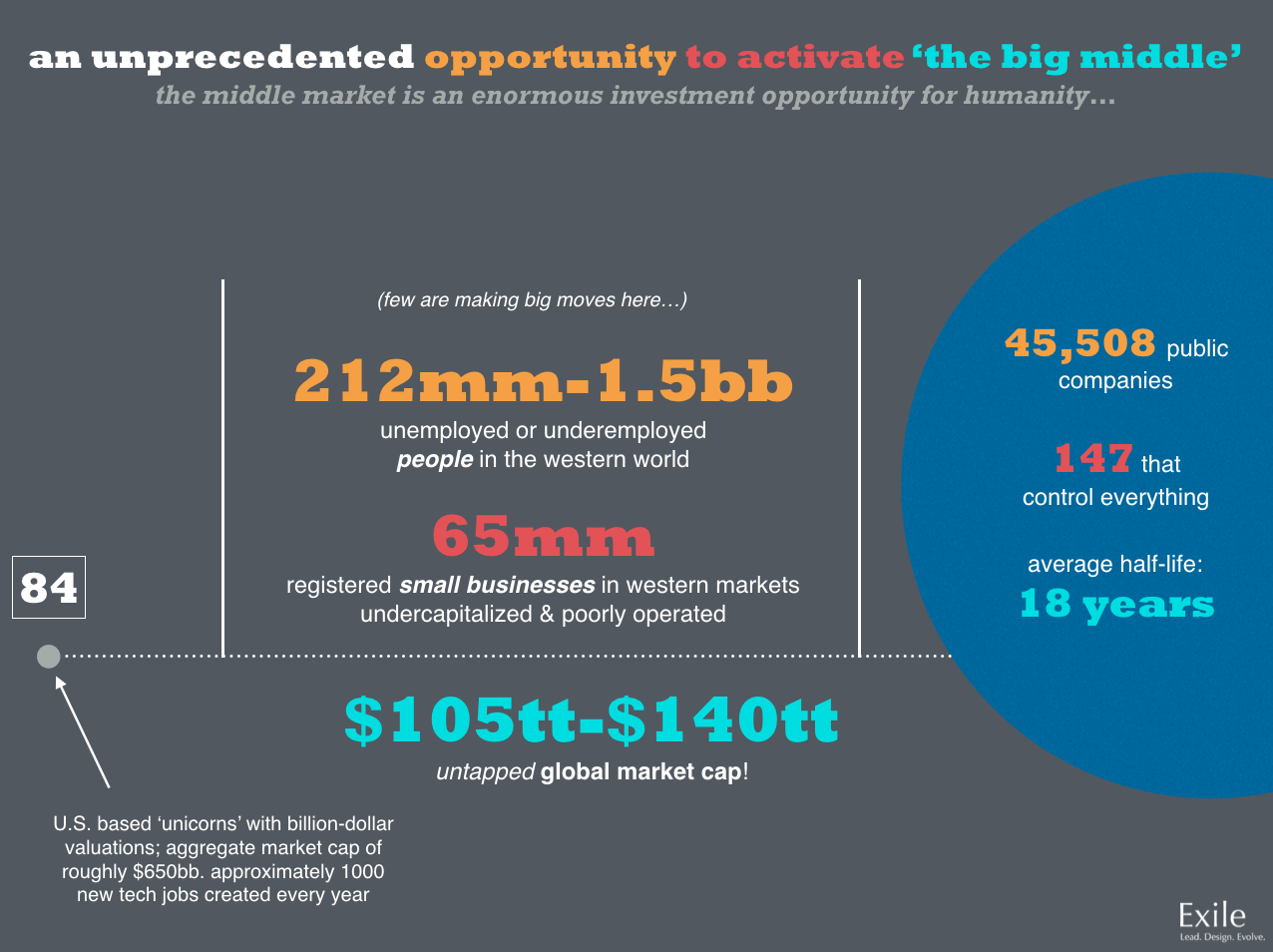

The ‘middle market’ can be described as a long-tail of 65mm small or early stage businesses in the western world (those which have been in existence for 7-10 years or less), roughly 15mm in the U.S., that actually drive the economy forward. That is, if they are supported.

As discussed in a few recent pieces, the untapped global market capitalization for this middle sector is between $105t and $140t.

Yes, that’s right — trillion.

Now of course, not all of these 65m companies contribute directly to upleveling GDP or GNP ratios; about 30% — 40% of them do, since they actually produce and distribute resources we need for basic sustenance (food, water, housing, healing, etc.).

So when we talk about stagnating GDP, the direct correlate is active investment in companies that drive economic stability and growth.

Reinvestment in operations and assets that larger companies don’t have to own outright provides them with the opportunity to vet new or emerging markets without incurring the kinds of operational risk they might take on through somewhat shaky mergers and hasty acquisitions.

This is precisely where the ‘Amazon Factor’ really comes into play.

The Giant with Opportunistic Chinks in its Armor

Two bits of history about Amazon that aren’t commonly discussed are really important to the story of how it will help build up the ‘middle markets’:

Its (poor) labor practices.

Its significant losses in warehousing.

The first shows us something about large-scale retailers, offline or online — they are not impervious to human resource management. Executive leadership aside (but not recused), Amazon learned the hard way that the methods by which it handles its people within the delivery supply chain cannot be overlooked. This lesson amplified when Amazon came under fire for labor abuses in more than just a few of its warehousing locations.

Between the years of 2002 and 2013, Amazon saw escalating employee turnover rates, some years in excess of 23%. As far as contractors go, service contracts with vendors went up by almost 5% year-to-year. Amazon has since improved its employee incentive programs, but turnover is still high.

So the implications with the labor pool are two-fold:

- Amazon can’t micromanage its workforce and continue to scale (automation/robotics will solve part of this, but of course, not all of it);

- As such it will invest, acquire and partner with more and more independently operated outfits, particularly in ‘new’ industries like food, wellness or energy.

The warehousing situation is also quite interesting.

At the time Amazon started aggressively purchasing warehouses to build up its distribution infrastructure (around 1998), America had come out of a fairly recent real estate bubble. Amazon made smart purchases at the lower end of the market — whatever it didn’t operationalize, it held as an asset on the books, and would either convert or flip that asset based on economic conditions, in some cases taking the loss (a writedown). It did the same again in 2001, after another bubble. And in 2008, when we went through not just a real estate bubble, but a major recession.

But here’s what really happened: While people still purchased food, clothing and entertainment, in each period or cycle, Amazon underestimated the elasticity of their purchasing power.

In other words, the company experienced unpredictable shifts in consumer behavior, which affected its ability to scale (and, naturally, to boost its stock price).

So imagine a company, like Amazon, at this point in time, having all of your personal data, understanding your product interests, and closely tracking your purchasing patterns, yet NOT being able to predict your movements or transactions. Pretty strange, right?

With this, we find two very critical implications as they relate to today’s markets:

- Price elasticity (how products and services can adjust to market fluctuations) cannot stave off imbalanced supply-and-demand dynamics;

- Monetary elasticity (how cash or debt can adjust to market fluctuations) cannot stave off imbalanced asset flows.

While Amazon has flirted with establishing its own, full-fledged finance and credit services division (like many large public companies such as GE, Amazon has cash and credit facilities set up through its venture investment arms), it has also seen how difficult that is with regulatory snafus and general liabilities in the consumer markets. Lobbying seeks to solve part of this, although the method in and of itself has its own challenges going forward — we’ll address this is in a bit.

So, this means that Amazon is getting really good at sourcing people and infrastructural components (outsourcing) to have its impact on the markets. Which makes a lot of sense.

From Quick Delivery to Quick Sourcing

Here’s where things get even more interesting.

As we touched upon earlier, the so-called ‘gig economy’ has revealed a profound shift from manufacturing jobs to service jobs, those of which are often temporary, or, service vocations by which people have ‘multiple jobs’.

While it is true that service jobs garner higher wages than manufacturing jobs, wage growth has stagnated, and overall, has been in steady decline for the last 25–30 years (local regions + per capita figures can tell different stories; this is an overall decline). This figure can be calculated by looking at labor force participation rates against GDP and GNP levels — elements mentioned earlier.

What this tells us is also revelatory: Wages will soon have to be replaced by things like civic dividends, stakeholder royalties and various forms of public/private equities.

Part of this can be attributed to current market mechanics.

In the case of corporate dividends — which are basically cash payouts on equities to preferred shareholders, often in the form of stock buybacks — we find financial instruments acting as assets reaching their thresholds (also known as ‘asset bubbles’). A threshold simply means that the asset can’t earn any more payout or equity value. A similar dynamic can be seen with equities (stocks), in which speculative or speculated value has very little to do with productivity rates, profit margin or even internal rates of return and cash-on-cash multiples, let alone P/E (price-to-earnings) ratios.

Nowadays, and in part for the factors just mentioned, public companies grossly inflate their equity value. They create all sorts of fancy instrumentation to extract that artificial value or attract more of it, and then redistribute the artificial profit and/or inflated equity to select relatively few shareholders (predominantly majority shareholders).

Amazon is a glaring exception to this rule in the fact that its speculative value (its stock) is its asset value, simply because it uses its enormous cash and credit lines to reinvest in the market, as mentioned, on a dollar-per-dollar basis. In other words, Amazon has incredible skin in the game, whereas its competitors, proportionate to their earnings and net cash flow, literally sit on inordinate piles of cash and credit that are more or less ‘inactive’.

So what we have here is a special kind of doozy: a company with the highest perceived market value in the world, with the most skin in the game of any company in the world.

Which leads us to the next emerging phenomenon: asset bundles.

Creating New Value in Asset Bundles (versus Asset Bubbles)

Given all the talk at the highest ranks of financial and economic analysis, it still remains to be seen if the equity markets will actually ‘implode’ or not.

Typically before a ‘trigger event’ (a major crash) the stock market trades at all-time highs, which it has been doing going into and coming out of the U.S. presidential election. That said, as of this writing (Wednesday, May 17, 2017) the markets are starting to exhibit downturns, particularly in the financial sectors. Alas, this moment in history is quite different from any other.

Dividend (buyback) activity has softened quite a lot, and the bond markets are doing some strange things with inverse yields that are propping up activity in precious metals and other ‘alternative’ asset vehicles. Rate changes through Fed/central bank policy will also produce some nasty cyclical effects in terms of inflationary and deflationary risk, depending on which side of the market you sit.

It’s also very likely that the U.S. petrodollar will rally in several cycles for a tight window (18–24 months) before oil starts to see serious EROI declines (we’ll return to the energy return on investment factor shortly). As such, the dollar, for one, won’t entirely collapse as some have speculated, but it may see some harbingers, such as SDR (currency handbasket) consolidations, significant trade agreement revisions (post TPP and TTiP), and more contractions in labor movement — all of which will have highly nuanced macro- and microeconomic effects.

Are we still insanely over leveraged across global markets? Of course we are. Debt is at 325% of global GDP, at last notice.

Yet, we must also remember that the current financial markets are not based on debt volume or debt overload so much as they are volatility. Volatility can also be contained. ETFs and other index trading platforms are classic examples: Nowadays, you can trade on bets, not real assets.

That said, we are also seeing unprecedented market distortions such that ETPs and VIXs are actually driving down volatility, which raises serious questions about hedges and microtrading in general. At a systemic level, what this also shows us is the lack of signaling investors receive as trading and asset flows are wildly disproportionate, which also gives us some idea of just how much assets and speculative instruments are being handled ‘off the books’.

Hedge funds are a great example of these incredible market distortions — many have shut down or have focused almost entirely on moving cash around, what some call ‘smart money flows’. This really just means that smaller fish follow the capital leads of the big fish, and the big fish follow other big fish, making what they perceive to be ‘safe bets’ through currency trades and the like.

For now, as long as debt moves around — and in some instances is written down — and as long as the majority of real assets remain in their thresholds or bubbles (natural resources, commodities, etc.) as held by wealthy portfolio owners, we can actually ‘get by’ as a global economy until we activate a far higher percentage of available capital towards new infrastructural investments. These investments through startups, early stage and middle stage businesses are what kickstart productivity and real growth. As mentioned in previous writings, there are $289+ trillion on offer for ‘impact’ investments alone, worldwide.

To put it simply: Wealthy folks don’t want to lose their asset value, and bankers don’t want to lose their volatility. The mitigating factor? The middle markets. In other words, that gigantic opportunity space where you, me and everyone else has to earn or create a livelihood.

So, what matters right now, for Amazon in particular, is how it develops, structures and redistributes new assets. New assets are the ‘fuel’ of the middle markets.

And, this is where quick sourcing comes into serious play.

We’ve established that Amazon has tremendous skin in the game. Plus, it has the most robust infrastructure of any company on the planet. Literally.

Now, remember that metric economists like to use called labor force participation?

This is how new asset bundles will form.

What has happened historically is that labor forces migrate and then change composition as they ‘resettle’, or, as new ‘laborers’ emerge in a local market. Cases in point: Mondragon, the Ecuadorian co-ops, or Kalundborg.

We’ve also seen the darker side of it with coalition or collusionary movements in the States — a great example is what automakers did to parts and manufacturing suppliers (and vice versa) to force changes in labor and price elasticity during the Lee Iacocca era. This phenomenon of shifting ‘unionized production’ has spawned heated debates among politicians, economists and investors for decades, and has sent Marxian interpreters into philosophical frenzies.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are also great examples to refer to across brick-and-mortar retail domains, such as supermarket chains. Here, labor participation has forced the hand of new, employee-owned models found with the likes of New Seasons and Publix. Publix currently has a market capitalization of $15.39b and is steadily expanding its footprint of stores.

In every case, you find a distinctly powerful relationship between the people making the market (its operators and consumers), and the people trying to control the market (banks, financiers, unions, etc.) all in various forms of asset (in)elasticity.

In all cases, assets are neither regenerated (reused or repurposed), nor are they redistributed such that suppliers, operators and customers can mete out imbalances with supply and demand. Food shortages are a great example of these imbalances — they happen far more frequently than you would think, and oddly enough, with the major ‘food deserts’ being in the largest cities with the largest logistics footprints, such as New York City and Los Angeles. With scarcity models that naturally limit resource creation, utilization and redistribution, we can see this playing out spades, hence the amount of recent retail closures — all businesses that don’t use adaptive operating models as they try to scale in their respective markets.

So, we know that assets and asset classes in general are severely hampered in terms of elasticity, which in turn affects production, which in turn affects distribution and, reflexively, spending or purchasing power.

If you look across every line of Amazon’s business ecosystem, you’ll notice that Amazon is set up to enable production, distribution and purchasing power, but it is not actually set up to create new, ecologically variant assets (natural resources, commodities, etc.), particularly at the local level. As proof, you can even calculate coefficiencies — what amount to significant standard deviations — between cost of goods sold and delivery windows. What this ultimately means is that near-time delivery, quality and great pricing are predicated on the ability to produce + supply whatever isn’t available at the time, and to do so without eating into your margins (pun intended).

So, while Amazon isn’t focused on creating new assets per se, nor does it necessarily need or want to, it can bundle assets for businesses and customers at various points within the value chain.

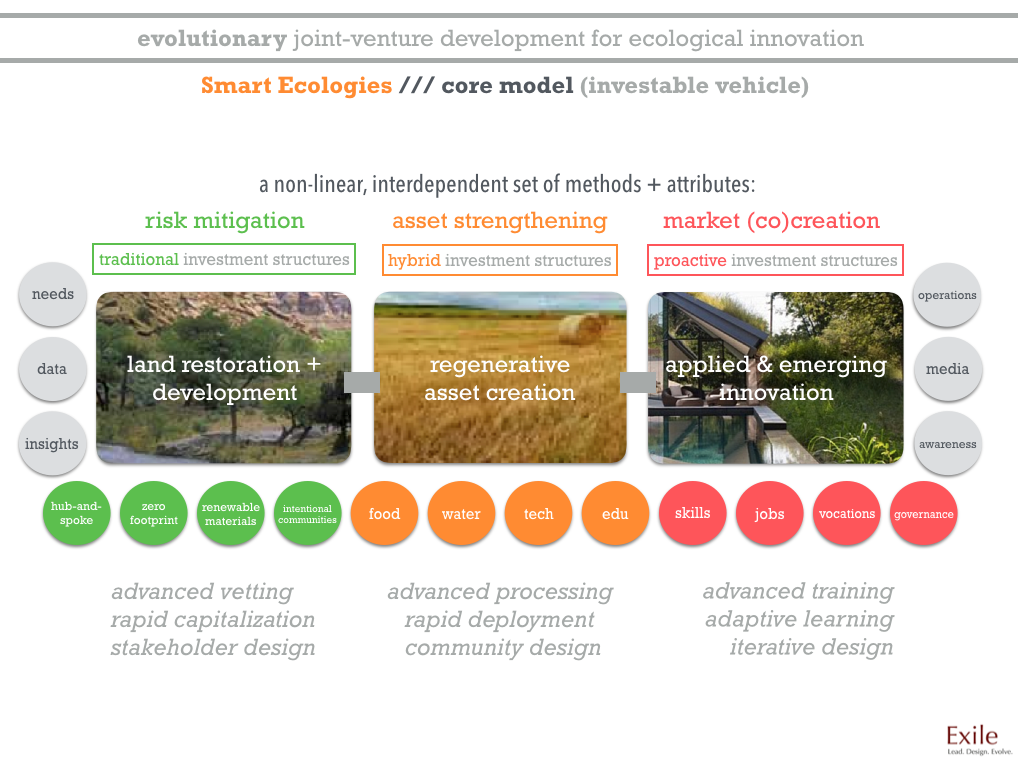

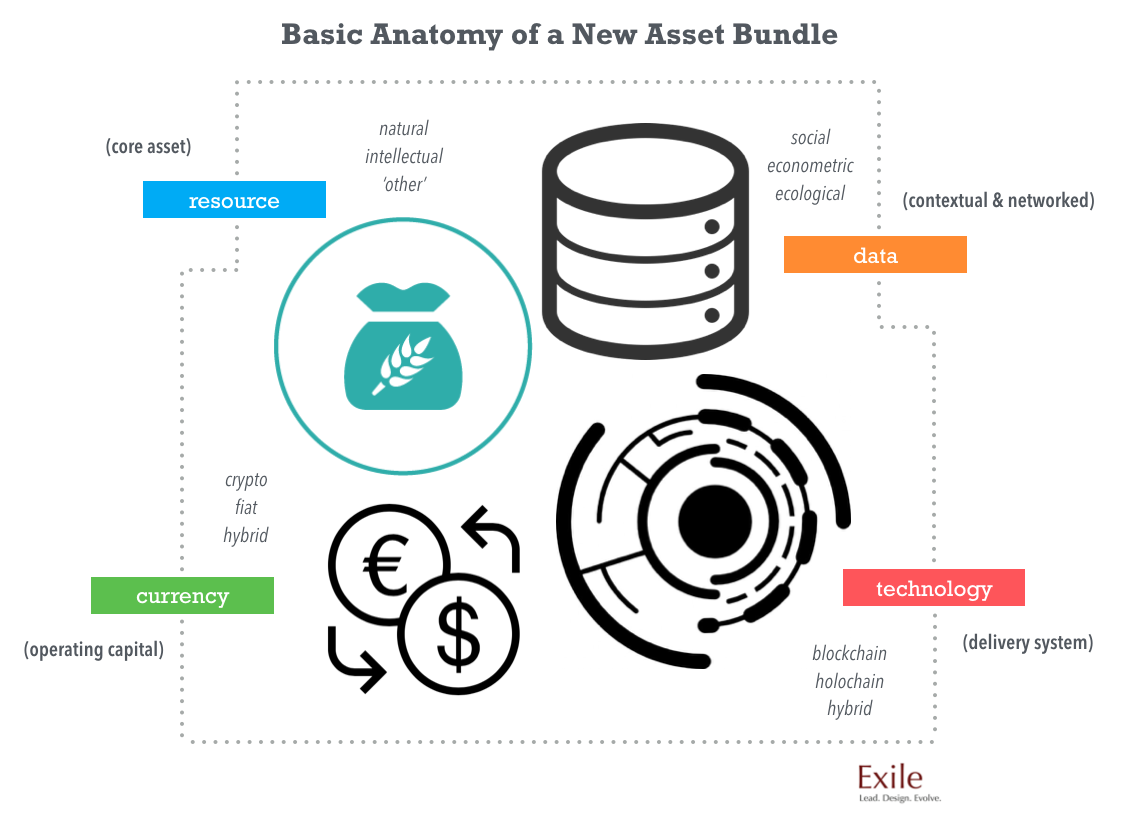

Here’s what a new asset bundle looks like, at least in its foundation:

The asset bundle is not a new concept by any stretch. Investment banks, as one example, have been toiling with bundles as investment vehicles for decades. These are not to be confused with collateralized asset vehicles or CDOs — collateralized debt obligations, otherwise known as derivatives, or in some cases, ‘asset securities’ — which are pureplay debt instruments that create the overleveraged structures which have gotten us into serious debt and asset woes for quite some time. What we are talking about here are real asset vehicles.

The difference now lies in how asset value can be determined — specifically through ecological variance — as well as in how that value can be adaptive to changing conditions. Technologies such as those built on the blockchain can parse out, divide and rebundle variant value, and this is the great promise of (de)centralized methods, particularly with respect to collateralization. More on that in a moment.

As far as remittance and accruable value tied to labor, or more humanely, ‘work contributions’ go, new kinds of dividend and royalty systems are being developed via blockchain-like platforms (such as the holochain) which will allow producers, distributors and customers of all types to reflexively and recursively exchange forms of value. This includes, but is not limited to, food, clothing, transportation, energy and even money.

Imagine that every local community has its own shared resource pool, labor pool and currency or credit system, powered, in part, by an Amazon-like infrastructure. We’re not far at all from that version — just one version — of the future.

A Reframing of Moore’s Law: Amazonian Economics

Technology has a funny way of making people believe that acceleration and exponentiality are magical, and that they can somehow replace our physical needs in physical spaces. More directly, current technology plays don’t create new assets. Cases in point: Uber, AirBnB and Facebook, which accelerate (dis)intermediation through the extraction of preexisiting resources — primarily labor in the form of transportation, housing, data, etc. — all to the tune of billions of consumer dollars.

But what we’re really facing is much bigger than magical thinking: we’re diverting to more and more forms of artificial value (oxymoronic, isn’t it?).

This really shows up in preconceptions around labor and civic participation, as well as governance and democratic reform efforts.

Naturally, economics and civic society are obliquely intertwined. This is the case now more than ever, as evidenced by the noticeably repressive corporate totalitarian system or plutocracy we have been experiencing in the States (call it ‘soft fascism’?) — deep state surveillance and travel bans are just two glaring examples. Surveillance in particular has far less to do with national security in the form of ‘terrorism’ than it does national security in the form of private money flows such that state actors and private interests can be kept in check by the titans of industry — monoliths such as Google, Facebook, Palantir, Twitter, Yahoo! and of course, Amazon.

A great historical example of preserving private money flows through resource extraction and extortion is what Smedley Butler described about the formation of the ‘Banana Republics’ in his seminal book, “War Is A Racket”. Had Butler and his mercenary groups been aided with advanced technology, who knows what the surveillance implications would have been. Nonetheless, the ‘silent evolution’ of state-sponsored privatization for corporate shareholder benefit is hardly a new thing.

Today, the natural reactions to this incremental butchering of personal and national sovereignty are civil unrest and the usual forms of activism, yet very little if any foundational changes can be tied to production or consumption behavior, other than the ways we produce and consume through, for example, mobile devices.

In other words, our overconsumptive behavior drives the very machine that continues to infringe on our civil liberties, if not wipe them out altogether.

From a technology perspective, we can easily posit that our affinities for ease, delivery and comfort are also the keys to a future of ‘totalitarian bliss’. Or, conversely, a more aware, committed aversion to these affinities and towards more equitable alternatives can create futures of abundance which allow us to produce, distribute and consume on our own terms.

This is what we really need to take hard, honest look at right now.

Dispensing with ideology and looking at current realities for what they are, we can make a logical assertion that our core economic problems and respective solutions are not really in fact technological — they are deeply ecological.

The giant gap that Amazon has yet to help fill, believe it or not, is also the biggest market opportunity, historically, we’ve ever seen.

And so now we can unofficially introduce ourselves to Amazonian Economics.

Amazonian Economics are as follows:

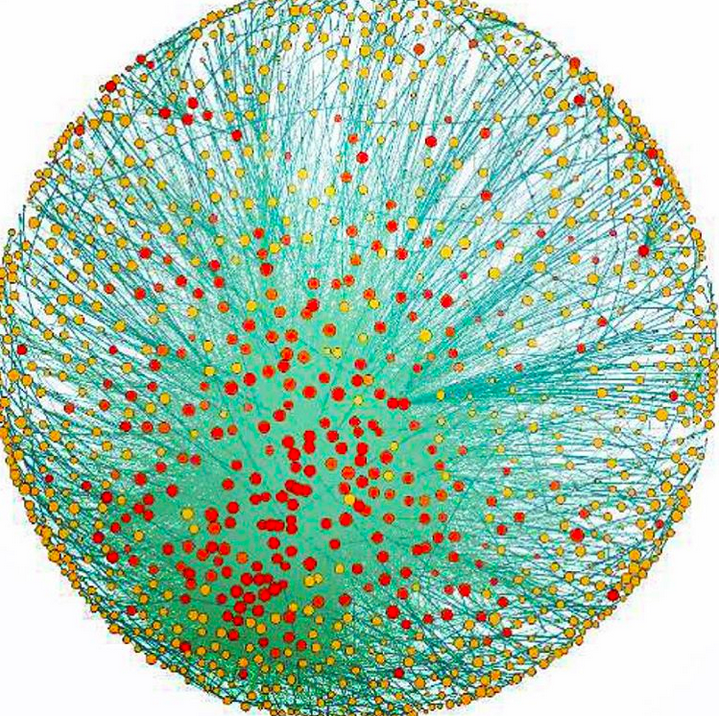

A highly ‘customer-centric’ company is also a high-risk company; therefore, the markets in which the company operates is subject to massive swings in price and monetary elasticity, along with asset unpredictability, such that the market gaps are huge opportunities for smaller ‘bit’ players… and/or for the company itself.

Now, we can look at what this means in terms of technological acceleration.

Moore’s Law (/mɔərz.ˈlɔː/) is the observation that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. This also means that the market value of an integrated circuit (a chip) becomes exponentially cheaper over time.

If every transistor (every chip) requires some form of value to sustain its growth, and every network is capable of producing new forms of value, yet the cost to deliver that value gets cheaper and cheaper, then we are left with two essential mechanics:

- A fundamental need for new asset creation in every network (and between specific nodes);

- A fundamental need to collateralize the value of an asset, especially as its intrinsic value is variant per ecological, geographical and social conditions.

A great example of this is how Patagonia has invested and reinvested in the production of its own commodities (assets) — such as cotton — in order to manage elasticity and have relevant distribution efficacy in local markets. Patagonia has created an expanded network of suppliers and producers out of its value chain, supporting those participants with capital and operational resources. Other companies like Natura have applied similar operational practices, and of course Mondragon’s model is almost entirely regenerative.

If you would, sit with this for a moment. It might just be the single most important duo of mechanics driving your future as a global citizen and an entrepreneur.

As to how value chains expand going forward, we can now look at the reinvented mechanics of collateralization.

The Anomaly Overlooked by Common Sense: Collateralization

Economists, finance gurus and cryptocurrency folks tend to ignore collateralization when building new capital structures or econometric models. Collateralization and asset creation naturally go hand-in-hand.

A big part of the artificial value problem mentioned earlier is that we have been tethered to a fiat monetary system that is almost entirely speculative — government contracts are very nebulous elements to back up a dollar or another monetary unit, mostly because they are subject to pricing and asset (in)elasticities, and they are not publicly ledgered. Hence, central banks like The Fed write monetary policies that have anemic effects on productivity, while having significant effects on lending, spending and trading.

On the technology side of things, we haven’t fared much better.

For example, in blockchain spaces (Bitcoin especially), many groups look at things like monetary velocity, network density or tokens as markers for variations of intrinsic value, whether a unit of measure is used as a currency, a credit, a smart contract or a form of an equity. Granted, there are many different distinctions for these elements, and a wide variety of development groups that are not aligned on what the technology should and shouldn’t do. All the while, as far as more popular ‘crypto-alternatives’ go, the value of Bitcoin is primarily determined in how it trades against other fiat currencies, which is not all that ironic.

But the central point is this: collateralized assets, or, the methods behind asset collateralization need complete reinvention.

Apart from ‘alternative’ (re)investments, large companies like Amazon can collateralize their investments and their assets because they have enormous perceived value to which cash and credit lines have safe haven. But in the case of smaller companies, the risks are far greater, especially if they are heavily indebted and/or their assets are overleveraged — which is all too common.

Truth is, banks don’t tend to lend because they are highly risk averse. Larger institutions, like big banks, view ‘small businesses’ as those having capital and asset reserves or EBITDA in excess of $300m. Smaller regional banks typically won’t even look at a small business deal unless it has EBITDA of $10m or higher. Many community and credit unions aren’t even allowed to lend tranches of cash or lines of credit to small businesses simply because their main source of revenue is just collecting interest on the money that depositors put back into their accounts.

So, it can be incredibly difficult to get financing from institutions, yet institutions hold a majority of cash and asset reserves. Which also makes it incredibly difficult to collateralize assets and investments. Meanwhile, we need far more flexible capital and resource mechanisms by which companies can get funded in their startup, early stage and middle stage phases.

Private banking has come a long way in the last ten years, as more resource-intensive private capital groups — family offices, private wealth funds, etc. — have become more and more autonomous in terms of acquiring assets and deploying financial resources. Private banking also shows us a side of privatization that has great promise, which is the ability to disintermediate inefficiencies with capital structuring and resource deployment. In some cases, privatization can also push necessary infrastructural innovations otherwise stifled by regulation — we’ve seen this play out in many cities throughout the U.S. and Europe with the development of waterways, agricultural systems, electric railways and the like.

Now that we can see a reframing of Moore’s Law, and we see the critical importance of asset creation through Amazonian Economics, we can also see a critical role that companies like Amazon can and will play which will disintermediate banks and other financial entities with respect to collateralization.

In this sense, asset collateralization works in a two-way capacity, rather than the usual one-way capacity that only serves investors and primary shareholders.

i. The first is backing up the invested capital itself through a special kind of dividend tied to the present, future and transferable value of the asset it intends to create. (This already exists in various forms, albeit without ‘open’ versions.)

ii. The second is taking the exchange at present value and then backing it up by the reputation of the network, such that future value is guaranteed and also capped. (This exists in ‘futures’ trades, for example, but network reputation is not factored in.)

The result of these two exchange actions is an overall value that is completely non-speculative such that performance, operational capacity and actual market demand factor into the capital itself (as represented in the data). Deeply human (microeconomic) attributes can factor in as well, and ecological variants — geography, resource pool, resource deficiencies, resource utilization, etc. — will also determine transferable value.

The process just described is, in more rudimentary terms, the way Argentina collateralized its farming subsidies in a downturn, as well as how organic farming coalitions organized themselves. There are plenty of other examples of this in smaller industrialized countries where both banking and civic infrastructures simply could not generate new forms of value, speculative or otherwise.

In the U.S., some private groups are buying up entire towns and bankrupt municipalities, developing new infrastructures, creating more open governance and subsidizing the development through public-private banking mechanisms.

In all of these scenarios, we find that localized methods for handling variance (conditional shifts) are critical to repairing broken infrastructures.

So now that we have mechanisms for authentic exchange and diversified value, we can now explore the possibilities of how assets can be regenerated to sustain that value.

The Common Principles of Asset Regeneration

By now, some readers might be saying to themselves: “…But Amazon has always supported the middle market — it has entire divisions dedicated to small business enterprises!”

This is absolutely true. Except for one major caveat: What defines ‘small business’ is increasingly becoming more elusive, and a lot more complex.

Specifically, businesses are more interdependent than ever before.

Over 75% of small businesses are vendor businesses, which means they provide a product or a service in limited demand. These are essentially commodity-based businesses. Some have real, somewhat sustainable assets — such as upgradeable software, hardware, real estate or food products — but most rely on the assets of other larger companies to which they can supply supporting products and services, or repackage products in second- or third-tier capacities.

In our current contexts, this presents a unique supply side problem which results in oversupply and severe price and asset elasticity. This kind of elasticity is tough on smaller businesses because it requires them to quickly scale up and scale down in ways that cause tons of operational and logistics inefficiencies.

Case in point: A popular startup and organic produce supplier (out of respect we will leave it unnamed), which is now having to overhaul its delivery systems to compensate for varying load sizes, delivery windows, inconsistent wholesale pricing well as inconsistent produce quality. In other words, the company already has a scale problem in its limited market footprint even as demand for quality perishable organic goods is increasing at a steady rate.

It needs something akin to elastic scale.

Now imagine that a fairly well-capitalized ‘small business’ with healthy EBIDTA like this takes a totally different approach. How would it achieve ‘elastic scale’ and remain competitive at local levels, i.e. by maintaining intimate relationships with other producers/suppliers?

The answer here is three-fold:

- By incubating regenerative produce banks (places that can grow produce, regrow produce and reuse elements like water, soil and solar energy);

- By managing load distribution through transfers with other partner suppliers, even some who are considered to be competitors (akin to a resource hub or a co-op but far more integrated);

- By licensing the delivery/logistics to a ‘full footprint’ operator and/or entering into a revenue share model based on the factors listed above (like load balancing).

(An aside: The company is doing some of the aforementioned, the efforts are just not fully integrated.)

Let’s look at another example that is even more extreme in terms of elasticity — a wholesale cannabis supplier.

The cannabis industry is unique for many reasons, not the least of which is the fact it is a very high margin business that deals almost exclusively in cash. Here we see the other side of the elasticity coin, in which high supply and high demand are coupled with poor inventory management, delivery inconsistency, product inconsistency, potency uncertainty and no really robust infrastructures, in particular POS (point of sale) softwares, that can easily facilitate these elements end-to-end.

Some dispensary models have adapted by growing the flower (the cannabis plants) on site, extracting its elements there, testing them and then packaging the products all in one place, controlling inventory and price dynamics according to what the market will bear. Others have gone for Starbucks-like retail experiences, in which local supplier relationships are critical. Yet, for the most part, dispensaries don’t do well and most retailers are gun shy about putting cannabis products on their shelves, due to permitting and inconsistent local legislature from county to county or state to state.

From a macroeconomic standpoint, you want businesses in perishable goods or cannabis to succeed for three reasons: They provide jobs, they provide significant tax revenue, and in some instances, they offset farming subsidies which do not and cannot support the ‘food deserts’ or ‘product deserts’ mentioned earlier.

Traditionally, Amazon along with other software providers like Cisco or Oracle would figure out a way to support these kinds of operations, primarily through customized software solutions.

Nowadays, Amazon supports many businesses who have these profile types, but the difference is not so much in how Amazon can optimize inventory and delivery mechanisms, but in how it can provide support in regenerating the resource pool itself.

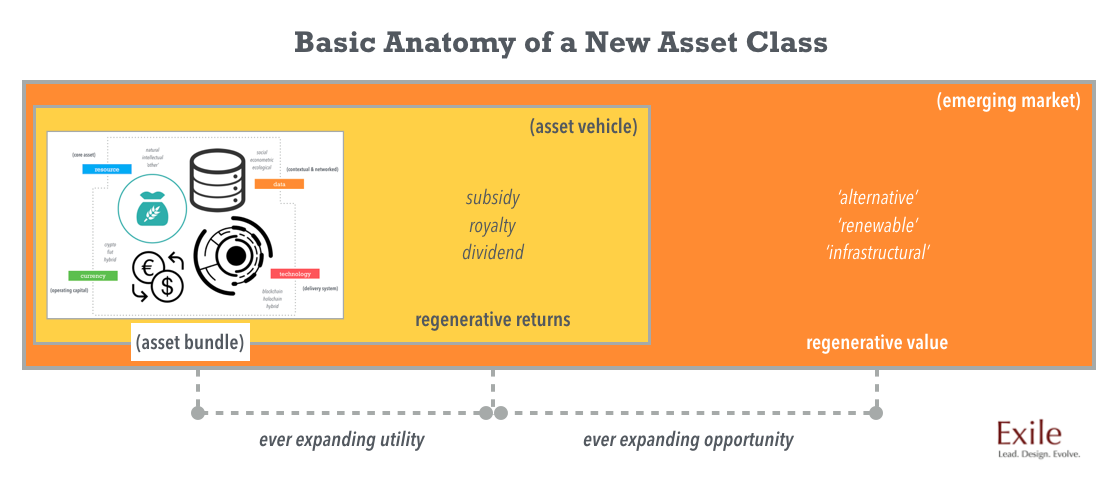

Hence, the ongoing, sustained value of the asset bundle. And where asset bundles are maintained, new asset classes form. This is the lifeblood of a ‘new’ economy, at least in terms of where value and exhange can diversify and expand without the normative market perversions of growth and scale.

So, the Common Principles of Asset Regeneration are as follows:

a) Resources of sustenance (food, water, energy) must be accurately maintained and protected;

b) When those resources become fully (re)usable assets, the physical elements (produce, water, energy) must be (re)distributed and consumed wisely, along with the non-physical elements (data, cryptocurrencies, credit, royalties)

c) Any and all elements must be regenerated (reused, repurposed, reconstructed) such that elasticity — price, product and asset elasticity — is controlled and managed.

Here are some alarming stats to back up these principles:

- Over 40% of the food that is produced and distributed in the U.S. is wasted

- Over 85% of municipalities do not have reliable or ample transportation and storage infrastructures to handle power and/or food outages

- Over 70% of all state tax revenue, in aggregate, comes from the sale of products, as well as taxes levied on small businesses (producers & suppliers)

- Local and state economic GDP figures are totally disproportionate with GNP outputs, primarily due to a lack of data and viable (con)census pools

- Underemployment rates are directly correlated with inconsistencies in GDP and GNP accountability

Now that we have established a clear framework that outlines the dynamics between labor participation, sourcing and elasticity, we can start to evaluate the staying power of businesses and industries that are (un)prepared for the radical shifts we are experiencing in the ‘Amazonian Economy’.

The Potential Winners and Losers of Amazonian Economics

Unlike other monopolistic leaders, Jeff Bezos has acquired relatively few companies since 1998. His three most important acquisitions — Zappos, Twitch and Kiva Systems — are emblematic of his vision for a complete product and media ecosystem. To boot, his individual purchase of WaPo (outside of Amazon) shows you just how committed he is to tailoring an end-to-end experience for customers that is unrivaled. Specifically, Bezos sees that bundling critical journalistic information with products, search and delivery is the Holy Grail. And it is, at least in his version of the future.

(Also, a quick point of clarification: When we’ve mentioned reinvestment, we’ve been primarily talking about Amazon’s constituent businesses, not acquisitions of outside businesses, although the company does invest quite a lot in the partner companies in its product + service ecosystem.)

That said, Amazon and Bezos, still have much to sort through, mostly because the lines are being blurred between competitive revenue and cannibalized revenue from market partners.

Here, we can identify a few factors that are critically important.

The first is the active revenue that Amazon can seize from service businesses, and already has.

The second is the passive revenue that Amazon can seize from publishing + media businesses, and already has.

The third is the shared revenue Amazon can co-opt from ecosystem partners, and already has.

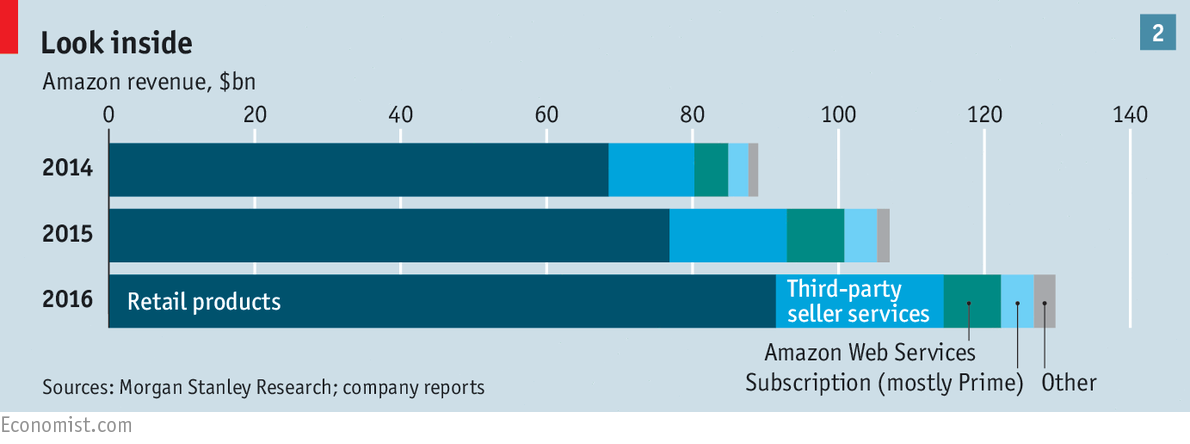

Yet, what’s interesting to note is that its revenue streams remain relatively undiversified given all that’s been addressed, and all that’s at stake.

Media businesses, particularly marketing, advertising and production outfits, are the most vulnerable simply because they typically don’t have sophisticated infrastructures to support their clients, and creative services can be reliably outsourced. Media and advertising holding companies are a bit safer (not much), simply because they have many long-term contracts, and like consultancies, they profit heavily from the operational inefficiencies of their clients.

Naturally, retail businesses are in serious jeopardy; in addition to all the closures of stores, there is also the latency with which businesses such as apparel companies develop their own self-sustaining operations (remember: Patagonia). This will prove to be more and more of a nightmare for clothing brands in the months ahead. New apparel companies have the benefit of ‘starting with a clean slate’, and many of them are getting very smart about how they operate and scale horizontally with supply chain partners.

Granted, it’s taken a while to get to this point of total market disruption (Amazon just had its 20-year IPO), but now Amazonian Economics cannot be denied.

As this author wrote to P&G’s Chief Brand Officer in a recent online thread:

Brands actually can exist without advertising. A wild provocation? Perhaps. Yet, it may prove to be more of a reality in the short days ahead as the economics of doing business reflect massive shifts in lending and spending power. Auto and home lending bubbles are just two leading indicators.

The quick, deep erosion of the middle class in particular is dictating how companies plan adaptively and the ways they (re)generate new forms of value that support people in struggle (many of their customers), as well as how resources are better managed to significantly cut production and distribution costs. On the technology side, Amazon is rendering advertising a secondary market as it presents industries and marketplaces with a fully robust, end-to-end platform that can offer people whatever they want, whenever they want it. This includes the capability of bundling that level of immediate access with sophisticated data, storytelling and journalistic components. Match drone logistics with lightning fast cloud delivery, and you have a leviathan at the gates.

What all market actors need to prepare for, right now, is the dangerous nexus of high consumption against revenue tied to runaway debt, less jobs and rate hikes that, alone, will not stimulate real, sustained economic growth.

In effect, brands that understand and embrace these dynamics can actually build new markets, generate new revenue streams, create different modes of authentic outreach and develop real relationships with local communities + key stakeholders. As for shareholder value, the persistently high costs of paid media and the still largely indecipherable ROI of continuing to ‘market to’ or ‘market at’ customers through endless persuasion and interruptive advertising tactics should prompt far more decision makers across brand, innovation and operational domains to transform their strategies. One could assert that, finally, after years of avoidance, the inevitability of great change is now here. We’re entering a whole new paradigm.

Not so surprising, P&G has been generating lots of direct sales revenue through Google and Amazon (we know this firsthand because it is a customer of one of our partner/portfolio startups, Faveeo). Alas, disintermediation is not just an attribute of outside or ‘edge’ players, but a behavior that the biggest companies on the planet are exhibiting as they face their own operational challenges. For many, these are also deeply existential challenges.

As we head further into policy uncertainties marked by opaque moves at the presidential and congressional or parliamentary levels, companies can no longer afford to ‘hold onto’ the same models for operating, developing products and services, as well as how they distribute those products and services through their supply chains. While this may sound obvious to industry ‘innovators’ — and has been discussed in various iterations for the better part of three or four decades —the truth is that very few if any innovations are actually providing viable economic alternatives to the incredible shifts we are undergoing in the markets, and will continue to undergo.

To be even more direct: Fancier branding, growth hacking, optimized advertising, programmatics, lean operations, artificial intelligence, product innovations and deeper customer experiences cannot and will not, in and of themselves, ‘fix’ our economic woes, especially if the middle markets (and the middle class) are not supported through proactive means.

In the same way that Henry Ford decided to create a market for his own employees, and Jeff Bezos sees his workforce as the progenitors of knowledge domains for future exploitation, we are on the cusp of a complete market reset.

So here’s the short list of potential winners:

- Service businesses that can also build products in the form of civic utilities

- Product business that can easily integrate with other utility players

- Commodity businesses that can create asset bundles as well as manage asset flows within emerging markets

And the potential losers:

- Service business based on utilization; ‘non-market makers’

- Product businesses within inextensible assets, most notably those which can’t create utilities with civic and/or commercial value

- Commodity businesses that cannot integrate their supply chains or share resources with other market players, irrespective of competitive status

Regenerative Economic Scenarios to Seriously Consider

Not so ironically, we are about to experience what can be considered a ‘deep, commodity-based fallout’ of sorts, which will give rise to thousands upon thousands of businesses that can provide nuanced value, and develop new assets that are relatively unfettered by traditional supply and demand dynamics.

EROI (Energy Return on Investment), as mentioned earlier, is a huge factor in this since oil products and food, clothing + home products at the mass commercial and submarket levels are inextricably linked (think about the distribution and packaging dynamics alone). Oil itself is looking at a complete dropout in value in the very near future, even if so-called ‘mid-tier’ infrastructural investments (drilling sites) are currently on the rise. This, of course, has enormous implications on foundational elements like hydrocarbons, which affect every major supply chain on the planet.

Businesses focused on alternative food, energy, wellness, media, education, data, privacy and currency systems will be the really big winners going forward, mostly because they provide the necessary new civic assets + utilities our society so desperately needs. And of course, Amazon has the footprint and flexibility to support these businesses and market ecosystems.

As we head further, by default, into post-scarcity conditions, here are some scenarios to consider:

_ lobbying → more open consensus ::: strategic positioning

Lobbies will look a lot less like policy strongholds and more like strategic coalitions that must seriously consider public interests as part of special interest initiatives.

_ governance → self-governance ::: local rules

As U.S. federal policies prove to be increasingly more ineffective and states exhibit greater autonomy, muncipalities and digital platforms will give rise (and are giving rise) to more local rules-based governance. This is just one of many great civic value streams technologies can and do enable.

_ finance → new capital structures ::: new dividends, new royalty systems

Blockchain technologies in particular are showing us that we can do away with time-consuming and lethargic capital processes, and instead can put more ‘intelligent’ resources directly in the hands of more and more people.

_ assets → new asset structures and classes ::: new public/private subsidies

As resources become more and more accessible, we can structure, underwrite and deploy more new assets and asset classes as viable investment vehicles, which also provide great alternatives to traditional debt as well as corrosive debt cycles.

_ labor → worker hubs ::: vocational skills, new creative categories

Laborers are not just being replaced by automation, but work itself is calling people to develop more creative vocational literacies (what we at Exile call ‘literacies of the imagination’). Creative categories will directly have huge impacts on new asset creation (and vice versa), as well as the ways in which networks and communities share resources in building more resilient and self-sustaining infrastructures.

_media → journalism, advertising ::: new journalism, interpretive communications

As more emerging markets take shape per the ecological factors described earlier, business, market and political contexts will be redefined, thus reshaping the ways we look at socioeconomic opportunities; myopic, ‘doomsday’ narratives will be replaced by solutions-based narratives that are grounded in multiple perspectives, such that networks of people (stakeholders and cohorts) will be able to coordinate sustained actions around solutions.

_education → project-based learning ::: learning hubs

As traditional institutions and their respective programs become less available and less affordable to more and more people, localized movements will support creative literacies, and provide communities with visibility into new ways of regenerating resources as means for their livelihoods and gateways into emerging micromarkets.

To Jeff Bezos: Open Ecosystems are Absolutely Essential

The ‘horizontalization’ of industries and respective market actors is showing us that closed systems have serious limitations in the expansion of business units. In Amazon’s case, it is becoming more and more obvious that its hockey stick-like growth is a deceptive bellwether for a significant market pivot of sorts.

To be clear, this isn’t about Amazon versus the rest of world, but what the worlds of business and civics are doing, and will do, with Amazonian Economics embedded within them.

As for Jeff Bezos himself, he must now create his own choices — a different set of choices — as a leader. Like his billionaire colleague Peter Thiel, Bezos is courting the Trump administration with a laser focus on guaranteed delivery systems and literal moon missions, while positioning his media powerhouses for ‘first look’ status amongst state department heads and their ilk.

Yet, there is also a more conciliatory element in the mix, which is Bezos’s legacy. And that legacy, we might also assert, is tied directly to the masses he has so handsomely profited from, while investing his own net worth into innovations that can, potentially, springboard an entirely new microeconomy.

In any case, it is abundantly clear that what Bezos might already know is what we must embrace as our only recourse as citizens, entrepreneurs and human beings.

Based on the emerging logic we’ve explored here, now would be a good time to lay out a set of postulates that flow from the (macro)economic axioms atop this essay.

Postulate I: Deploying resources to communities and local economies solves regional and global asset deficiencies.

Postulate II: Creating resources within communities and local economies also creates jobs in those areas.

Postulate III: Creating jobs that are based on resource-creation (asset pools) stabilizes earning capability for individuals and single family households.

Postulate IV: Earning capability translates into spending/purchasing power.

Postulate V: Spending/purchasing power determines consumption behaviors, including what is consumed, how it is consumed, and what is produced to be consumed.

Given that more and more people must be empowered to actually drive market expansion — rather than distorted versions of what is commonly known as market growth — we can also establish that open ecosystems, along with holonomic and regenerative design, are what is needed for that expansion.

For proper comparison, let’s acknowledge that the top competitors to Amazon are all closed product ecosystems, even if they may have strategic partnerships that open up their development capabilities. Apple is perhaps the most closed ecosystem of them all.

This is also dichotomous and interruptive. In other words, it is showing us that command-and-control systems are in their final hour, giving way to something far more ‘co-opetitive’ and collaborative.

Truth is, Apple is now in the energy business.

GE is in the software business.

Microsoft is in the governance business.

Yahoo! is doubling down in the media business, despite a major restructuring.

And Google is in the ‘quantum living’ business.

As we examined earlier, the difference between competitive and cannibalized revenue is shrinking by the day. Which means that Amazon has the greatest choice of them all: to literally expand outward. To ride those middle markets into the sunset, while many other businesses experience the sunsets of their existences.

And to Jeff Bezos, there is an offering of solidarity, clarity and ‘higher’ intention. There is perhaps the choice that Henry Ford never had, which is to make sustainable markets with all of the open ecosystemic might one can muster.

After all, Mr. Bezos, you are not Henry Ford. At least not in the ways history can now be created.

To all: Thanks for reading and considering the possibilities. It’s time to take critical action in building the markets of the future.

SUGGESTED READING: