The COVID-19 pandemic did not come out of the blue. It was a symptom of the fundamental structures of industrial civilisation, and it is an early warning signal for how this civilisation is rapidly eroding the very conditions of its own existence.

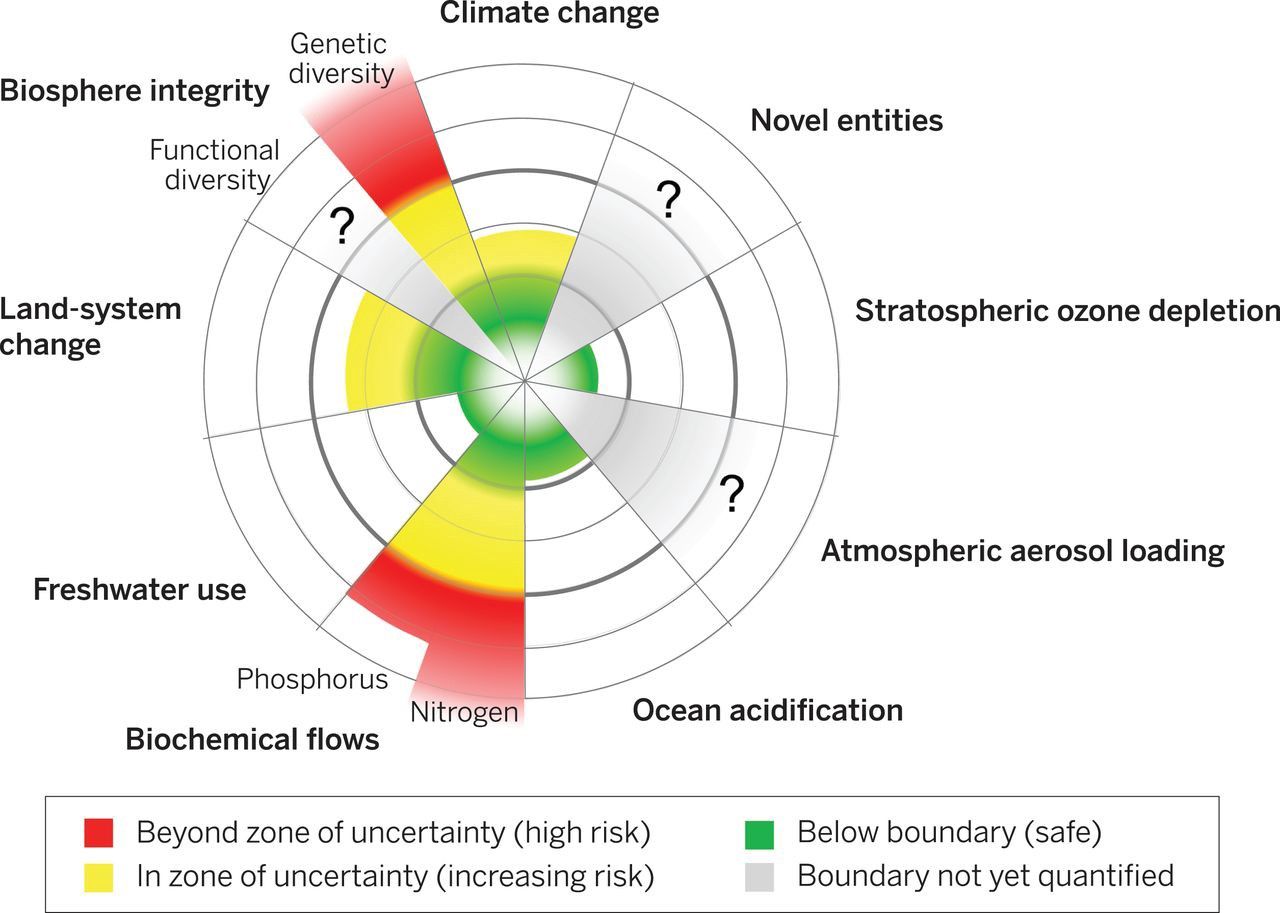

Over the last decade, environmental scientists have warned that human activities are increasingly at risk of breaching planetary boundaries, which define the environmental limits in which humanity can safely operate. As industrial civilisation increasingly encroaches on natural ecosystems, we are reducing this ‘safe operating space’ for human survival.

COVID-19 as a planetary boundary effect

Deforestation is one of the most intractable and yet most potent drivers of environmental crisis. It is also among the four out of nine planetary boundaries that civilisation was already at high risk of crossing five years ago according to research published in the journal Science.

Other boundaries we were on the brink of breaching at that time included the rate at which species were going extinct, levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, and the flow of nitrogen and phosphorus into the environment due to industrial agriculture. The further we breach these and other planetary boundaries, the greater the risk of irreversibly driving the Earth into a less hospitable state for humanity.

Five years on, the eruption of the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the extent to which we are gradually eroding and reducing this ‘safe operating space’ for human survival, a fact that is evident in the structural impasse we now face: allowing the virus to run through the population leads to massive fatality rates, collapsing healthcare systems, and crashing GDP; locking down to suppress the virus results in haemorrhaging demand, the contraction of multiple industrial sectors, and crashing GDP.

Both those scenarios entail mass deaths of vulnerable populations over varying levels of time, whether from disease or other socio-economic impacts. And a business-as-usual trajectory heralds more of the same.

A new report from the United Nations Environment Programme points out that the COVID-19 pandemic is essentially a dry-run for what could be an even worse pandemic. It is part of a rising trend in zoonotic diseases circulating among animal hosts jumping to humans, driven by core processes of industrial expansion which, if they continue, are bound to trigger the next pandemic.

The pandemic has thus pushed human civilisation into a state of retreat, as part of a much wider complex of expanding industrial processes.

Despite this, most governments, policymakers and business leaders do not understand the scale of the crisis or its true nature. They are clamouring for a return to business-as-usual to simply get economies moving again — with little reflection on how this would only reinforce the behaviours that got us into this intractable mess in the first place.

As the global combination of societal disruption, strained healthcare infrastructures, lockdowns and social distancing have strained normal economic activity, this has put as at risk of ditching seemingly costly environmental commitments.

Amidst such pressures, it is no surprise to see that deforestation driven by logging activity has accelerated in Brazil, Colombia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal and Madagascar during the COVID-19 pandemic — partly due to reduced environmental monitoring by authorities and harsh economic consequences amidst lockdown regimes.

In the context of the pandemic, does the challenge of deforestation represent industrial civilisation’s breaching of a key planetary land-system boundary around five years ago?

This question is particularly pertinent given that even while enduring one of its dire consequences in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic, progress in addressing deforestation is at risk of reversing — exactly when we need to be immediately putting an end to deforestation once and for all.

According to Professor Kees van Veen, Scientific Director of the Sustainable Society programme at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, the pandemic can be understood as “another expression of the fact that humanity pushes the planetary boundaries. The growing world population increases the chances that someone somewhere will be affected with a new and dangerous virus. These chances increase due to the fact that humanity exposes itself more and more to different virus ‘habitats’ by penetrating the biosphere deeper and deeper. Combined with our very efficient and global transportation networks between densely populated urban areas, viruses can spread very quickly and new accidents are waiting to happen.”

Yet COVID-19 is not simply a dry-run for the next pandemic — it is also, as executive director of the UN Global Compact Lise Kingo has said, a ‘fire drill’ for climate catastrophe. Deforestation is among the top drivers of global heating, contributing nearly a tenth of all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions due to tree cover loss from tropical forests. This is so large that if tropical deforestation were a country, it would rank a third in global CO2 emissions behind China and the United States.

The COVID-19 pandemic thus offers us a moment of awakening. We have arrived at an inflection point for the human species. The world needs new global approaches to tackle deforestation to not only avert the next pandemic, but to avert climate catastrophe, along with other forms of biodiversity collapse and ecological crisis.

If we fail to do this, we face an intensifying perfect storm of ecologically-linked catastrophes that will increasingly erode the ‘safe operating space’ for human survival. That process of erosion as we breach planetary boundaries has already begun. We need to bring it to an end, right now.

Deforestation: frontline of the unfolding collapse of civilisation

The problem of deforestation provides a powerful window into how intractable the processes of environmental destruction really are. These processes are baked into the core structures of production and consumption that sustain industrial civilisation as we know it.

In 2013, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessed that deforestation was responsible for up to 10 percent of human-induced carbon dioxide emissions. But when taking into account forest degradation — negative impacts on a forest’s structure or function which do not decrease its area size — as well CO2 emissions tropical peatlands, this figure rises to 15 percent. Satellite data for the period 2003–14 shows that tropical forests have now ceased to act as carbon ‘sinks’, because they emit more carbon than they capture due to deforestation and degradation.

Deforestation also exacerbates heating at local scales within tropical ecosystems. A recent study in Environment Research Letters “found local warming larger than that predicted from more than a century of climate change under a worst-case emissions scenario.” The larger the patches of deforestation, the more “extreme” are the local warming impacts. As a result, “the combined effects of deforestation and climate change on tropical temperatures present a uniquely difficult challenge to the long term public health, occupational safety, and economic security of tropical populations.”

But deforestation also endangers critical planetary ecosystems in more direct ways — ways which, if undermined, in themselves could endanger the ‘safe operating space’ for humanity.

Before the development of human civilisations, the Earth was covered by 60 million square kilometres of forest. As deforestation has accelerated due to the human footprint on the planet, there are now less than 40 million square kilometres of forest remaining.

In May, a shocking new study published in Nature Scientific Reports, by physicists Dr Gerardo Aquino of the Alan Turing Institute in London and Professor Mauro Bologna of the University of Tarapacá’s Department of Electronic Engineering, came to a stark conclusion based on examining this dynamic.

Their study in particular modelled human-forest interactions over the last few decades, along with its potential impact on the viability of human civilisation. Their findings were alarming. “Calculations show that, maintaining the actual rate of population growth and resource consumption, in particular forest consumption, we have a few decades left before an irreversible collapse of our civilisation,” the wrote.

Tracking the current rate of population growth against the rate of deforestation, the authors found that “statistically the probability to survive without facing a catastrophic collapse, is very low.” At the current rate of deforestation, they projected that all the world’s forests would disappear within approximately 100–200 years. As forests provide critical services to the life-support systems necessary for human survival on the planet — including carbon storage, oxygen production, soil conservation, water cycle regulation, support for natural and human food systems, and homes for countless species — “it is highly unlikely to imagine the survival of many species, including ours, on Earth without them.”

On that scenario, human civilisation would begin to collapse long before the terminal point for planetary-scale forest destruction, potentially well within the next two to four decades. The study authors write:

“In conclusion our model shows that a catastrophic collapse in human population, due to resource consumption, is the most likely scenario of the dynamical evolution based on current parameters. Adopting a combined deterministic and stochastic model we conclude from a statistical point of view that the probability that our civilisation survives itself is less than 10 percent in the most optimistic scenario. Calculations show that, maintaining the actual rate of population growth and resource consumption, in particular forest consumption, we have a few decades left before an irreversible collapse of our civilisation.”

This verdict would seem to indicate that there is an over 90 percent probability of a collapse of industrial civilisation due to deforestation alone — this is extraordinarily high.

Industrial overconsumption

Since 1990, industrial expansion has resulted in the loss of some 420 million hectares of forest overall, and the decrease of old-growth primary forest worldwide by over 80 million hectares.

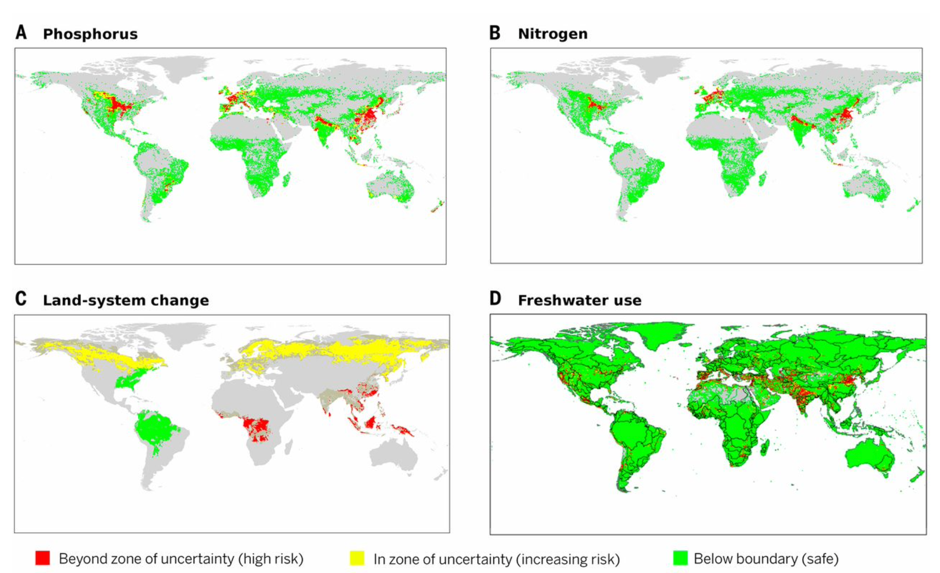

The main driver of deforestation and forest degradation is agricultural expansion, in particular large-scale commercial agriculture — which is responsible for some 80 percent of global deforestation. Between 2000 and 2010, the latter types of agriculture accounted for some 40 percent of tropical deforestation, and local subsistence agriculture for another 33 percent.

Of the world’s major political institutions, the European Union has perhaps been at the forefront of developing new legislative and policy approaches to tackling deforestation. But there are strong grounds to suspect that these approaches are not fit for purpose — and may well even deepen the challenge.

A new study by the EU Commission in February found that the agricultural expansion behind deforestation is driven by growing demand for key products — like soy, beef and vegetable oils such as palm oil, rapeseed and sunflower. And while the production of such commodities often takes place in developing countries in South America, West Africa and Southeast Asia, the reality is that much of the impetus for the production comes from Western consumers: approximately a third of globally-traded agricultural products linked to deforestation were consumed by European countries between 1990 and 2008.

Thus, deforestation is not just a problem outside the West. New research published in July in the journal Nature Research showed that deforestation rates in EU forests are picking up steam. Forests account for some 38 percent of the EU’s land surface area. They are harvested regularly for timber production. But between 2016 and 2018, the loss of biomass due to harvesting increased by 69 percent, compared with the period from 2011 to 2015. The area of forest harvested also increased by 49 percent over these time-scales. The study attributed this upsurge in European deforestation to increased demand for wood for timber and as a fuel, among other wood products. The “abrupt increase” in deforestation poses a serious threat to the EU meeting its climate mitigation targets:

“If such a high rate of forest harvest continues, the post-2020 EU vision of forest-based climate mitigation may be hampered, and the additional carbon losses from forests would require extra emission reductions in other sectors in order to reach climate neutrality by 2050.”

Yet in its recent efforts to address deforestation since 2015, the EU’s overwhelming focus has been not on its own direct complicity in deforestation, but rather on the role of external commodities. In fact, the commodity that comes in for the most trenchant criticism — as reflected in the most recent draft EU legal framework to stop deforestation — is palm oil. The proposed draft framework builds on the EU’s already existing approach: in 2019, the EU decided to cease categorising palm oil for biodiesel as a renewable energy product, and began implementing a planned phase-out.

Palm oil has undoubtedly been one of the major drivers of deforestation, particularly in parts of Southeast Asia. The region has experienced the highest rate of deforestation of any major tropical region, losing 1.2 percent of forest annually, compared to Latin America (0.8 per cent) and Africa (0.7 per cent). At this rate, Southeast Asia will lose three-quarters of its forests and 42 percent of its biodiversity by the end of this century.

While a major driver, palm oil is not in fact the biggest driver of deforestation.

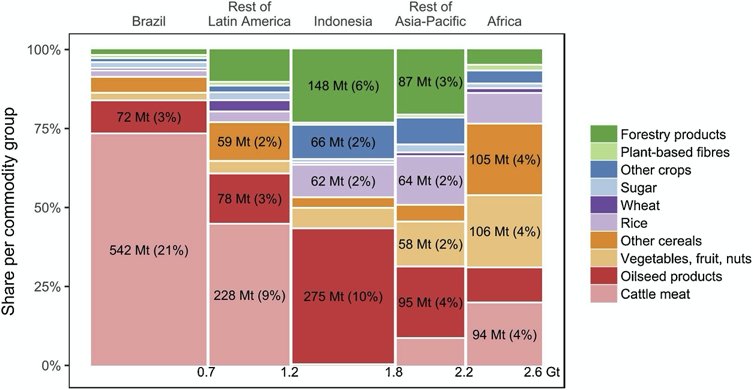

In 2019, I reported on a major new study in the Global Environmental Change journal which found that between 2010 and 2014, beef and oilseed production accounted for over half of carbon emissions from tropical deforestation. The study also quantified precisely which products were more responsible for deforestation than others.

It concluded that the biggest global driver of carbon emissions induced by deforestation is beef production in Brazil, the rest of Latin America, and Africa, accounting for some 34 percent of emissions. The next major driver is from oilseeds products such as vegetable oils, at around 20 percent.

The study was able to disaggregate responsibility for emissions in another way. Latin America overall bears the bulk of responsibility, accounting for just under a third of deforestation-linked carbon emissions, with Brazil alone driving a fifth of emissions. Overall, palm oil produced in the Asia-Pacific accounted for 14 per cent — a substantial amount, but still less than half of the former. It is also worth noting that by far the biggest culprit in Asia is Indonesia — one of the world’s biggest palm oil producers — accounting for ten percent of deforestation emissions. The other main palm oil Asian producer of course is Malaysia, which would fit within the remaining 4 percent of emissions.

This analysis builds on previous data. In 2013, a report by the European Commission found that between 1990 and 2008, “large imports of soybean products mainly from South America” accounted “for roughly 82 percent of deforestation attributed to the import of oil crops” into the EU. This contrasted with “palm oil imports from Southeast Asia, which contributed about 17 percent of deforestation associated with EU27 oil crops imports, imported primarily from Indonesia and Malaysia.”

Armed with this data, we are equipped to realise that the EU’s attempt to tackle deforestation through a de facto ban on palm oil for biofuels, while largely neglecting strong legislative and policy action to address rocketing beef and soy consumption, makes little environmental sense.

Indeed, a new study in July revealed that around half of Brazil’s beef exports and nearly a quarter of its soy exports to the EU could be from zones which were illegally deforested in the Amazon and Cerrado. The EU is thus directly complicit in the biggest drivers of deforestation, yet has done next to nothing to address this.

Ending deforestation: the policy toolbox

But the available scientific evidence suggests that the prevalent approach to stopping deforestation — focused largely on the strategy of boycotting particular commodities — is unlikely to work.

The ‘boycott palm oil’ approach has become a staple strategy in parts of the global environment movement, especially in the West. The idea is that by ceasing consumption of palm oil, Western consumers can directly contribute to reducing deforestation by alleviating the demand that is driving the expansion of palm oil plantations.

The problem is that several studies in recent years have shown that this strategy is not only unlikely to work, it is instead likely to have devastating environmental consequences.

University of Bath scientists recently showed in Nature Sustainability that banning palm oil could drive greater rates of deforestation, by switching demand to less efficient edible oils like sunflower or rapeseed which use more land, water and fertiliser, and have lower productivity and shorter lifespans. These other oil crops also store less CO2, and require up to nine times as much land to produce than palm oil. In the near to mid-term, the scientists found, policy should be directed at ensuring the sustainability of production because import restrictions would be ineffective in stopping deforestation or protecting the environment

The study confirmed years of previous research from scientists at the University of Oxford and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

A major study in Annual Review of Resource Economics published this year has provided further corroboration for these findings. The Annual Reviews study led by German scientists is worth noting as it is one of the most authoritative analyses of the best scientific literature to date. It confirms that the key challenge is related to the efficiency of palm oil, relative to land, water, energy and fertiliser inputs:

“The global demand for vegetable oil will continue to grow. Against this background, banning or curbing oil palm cultivation is not a realistic option. Given oil palm’s high land productivity, meeting the rising demand only through other oil crops would entail even more land-use change and natural habitat loss.”

Of course, as I argue below, we should not simply capitulate to the current likely growth in demand but do all we can to limit that growth through deeper systemic change. Yet such an endeavour will still take time, during which period — these studies show — a boycott-only approach would likely switch existing demand to more intensive and environmentally destructive oilseeds.

A boycott-only approach also tends to incentivise producers to find ways to circumvent the boycott, by accessing other markets (such as India and China), where environmental regulations are far less stringent. This once again undermines the entire point, and increases the risk of continued deforestation.

If bans or boycotts are not a viable solution, then it is time to face up to the fact that the conventional policy toolbox has failed. To stop the scourge of deforestation requires a much more joined-up approach, one which approaches the global challenge holistically. This also highlights the necessity of homing in on the solution which all these studies point to consistently: transforming production at source.

Toward a Great Forest Transition

While the global picture on deforestation is alarming, there are also real signs of change emerging on the horizon. Our task must be to leverage these indicators and accelerate them — before we hit catastrophe.

According the 2020 State of the World’s Forests report published by the United Nations Food & Agricultural Organisation jointly with the UN Environment Programme, the rate of global deforestation has been declining over the last few decades.

From the 1990s to the period between 2010 and 2020, the net loss of forest area decreased from 7.8 million hectares per year to 4.7 million hectares per year. One reason for this is that despite ongoing deforestation, new forests are also being established, both naturally and through deliberate planning.

But the rate of deforestation also appears to have declined in real-terms. In the 1990s, the rate of deforestation was around 16 million hectares per year. Between 2015 and 2020, this had declined to an estimated 10 million hectares per year. Around the same period, according to data from the UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre, the area of forest allocated to protected areas has also increased from around 4.2 million hectares in 1992, to about 8.2 million hectares in 2015.

This shows that there are grounds for hope that the rate of deforestation modelled by the collapse study discussed earlier can be dialled down dramatically.

But these are not grounds to be sanguine. In absolute terms, the UN report shows that global forest area still decreased overall by a colossal 178 million hectares between 1990 and 2020, an area about the size of Libya. Which means we have not yet really dialled down the rate of deforestation to a point where it can avert near-term catastrophic outcomes.

The other problem is that simply offsetting deforestation with new reforestation is not a viable solution — as doing so often fails to solve the problem of species losing their homes; reforested land might consist of pristine forests being replaced with commercial plantations; and forest regrowth does not necessarily lead to full ecosystem and biodiversity recovery.

So simply calling for the growth of new forests while rampantly destroying existing forests would not necessarily solve biodiversity collapse.

Nevertheless, a decade ago the Annual Review of Environment and Resources found evidence that part of the reason for the decrease in the rate of deforestation (despite it still being “alarmingly high”) is that “a handful of tropical developing countries have recently been through a forest transition — a shift from net deforestation to net reforestation.”

These forms of transition encompassed a range of different approaches within different regions. In Central America, a common approach was reforestation on abandoned land. In South America, private actors drove new forest plantations. In Asia, land-use policies restricting activities on forestlands and agricultural changes helped contribute to forest regrowth.

But the study warned that forest transitions alone would not be sufficient to protect primary forests. Land-use zoning — segregating off different areas of land for different agricultural, industrial, conservation and other purposes — was recommended, along with changes to the demand side in the form of “ecoconsumerism” and “new corporate environmentalism”, to accelerate “a transition in production systems and orient consumption toward less land-demanding products.” A failure to execute such changes would render the positive wins from forest transition processes negligible and end up driving increasing rates of deforestation.

The latest data produced from the Global Forest Watch project run by the World Resources Institute confirms that amidst the welcome evidence that slowing deforestation is perfectly possible even with a mix of inadequate policies, we are still on the cusp of losing even those potential gains. The data shows that primary forest loss was 2.8 percent higher in 2019 than the previous year. It also shows a gradually increasing trend-line in the rate of forest loss since 2002, despite some fluctuation.

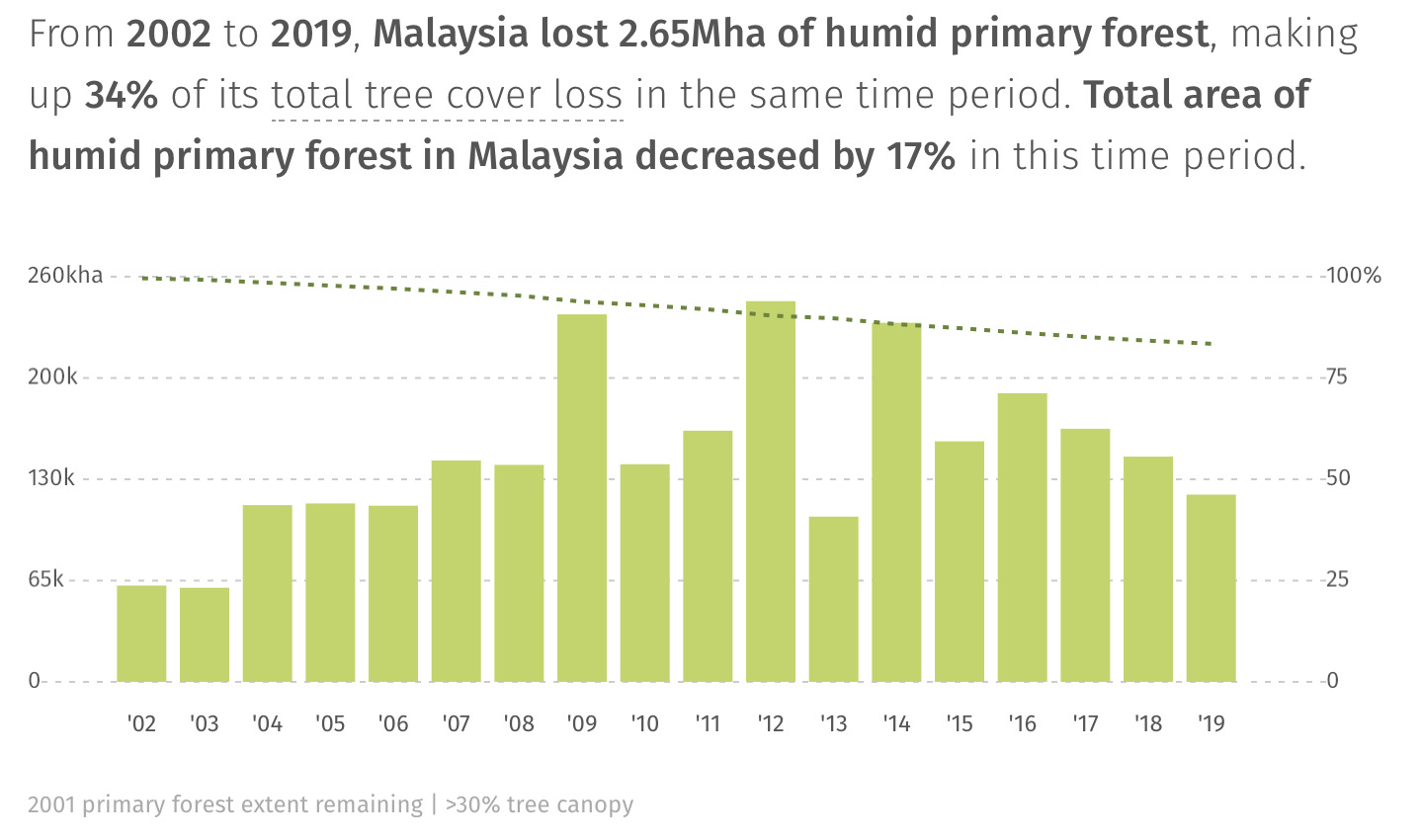

The data also confirms that the country that lost the most primary forest in 2019 was Brazil — where during the COVID-19 pandemic, deforestation has continued to accelerate. Palm oil producer Indonesia comes third on the list of the top 10 tropical countries experiencing the most primary forest loss, and the other major Asian palm oil producer, Malaysia, comes sixth.

Scaling emerging models of success

But while Brazilian deforestation has accelerated, there has been significant success in reducing the rate of forest loss in Indonesia and Malaysia. “In positive news,” noted Global Forest Watch, “primary forest loss in Indonesia decreased by 5 percent in 2019 compared to the year before, marking the third year in a row of lower levels of loss. Indonesia hasn’t seen such low levels of primary forest loss since the beginning of the century.”

Similar marked declines can be seen in Malaysia, where the decrease in the rate of primary forest loss also occurred year-on-year for three years. The decline also appears to be far more steady over a longer period of time, but especially over the last 3–5 years — and the absolute scale of deforestation is far below the level of Indonesia’s, which is a larger producer.

According to Global Forest Watch, the most likely drivers of this welcome decline include local forest conservation policies such as “increased law enforcement to prevent forest fires and land clearing, and the now-permanent forest moratorium on clearing for oil palm plantations and logging.”

In Malaysia in particular, most of the progress has coincided with the implementation of a new national sustainable certification scheme, Malaysia Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO). Established in 2015, after a new government came to power in 2018, it was announced that the scheme would be made mandatory by the end of the year — making it the world’s first government-backed, legally-enforceable sustainable certification programme for palm oil.

As a national mandatory scheme, MSPO differs quite fundamentally from the more well-known corporate-backed sustainability certification schemes such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). The RSPO scheme is not mandatory, but voluntary, supported as it is by some of the largest companies in the world involved in palm oil production from Unilever to Nestle. This also means that it is geared toward larger producers, making it far more expensive, complex and inaccessible for smallholder farmers who manage some 50 percent of the worldwide oil palm land.

It is no surprise then that a new study in Science of the Total Environment finds that over the last 30 years, RSPO certification has ended up sanitising long-term deforestation. The study assessed that most of currently certified production in Sumatra and Borneo are located in areas that were, in the 1990s, biodiverse tropical forests that were large mammal habitats.

The new Global Forest Watch data suggests that in contrast to the mixed results of RSPO, the MSPO scheme so far appears to be having a positive impact. Although there is little to no independent scientific literature available on MSPO’s efficacy, this data indicates that an approach backed by local enforcement mechanisms can be effective.

In 2017, independent Canadian conservationist Robert Hii, editor of CSPO Watch — which monitors certified sustainable palm oil schemes — visited palm oil plantations certified under the MSPO scheme in Sarawak. He commented for HuffPost:

“I knew that I was being shown the best of category but if the operations I saw are any indication of what Malaysian sustainable palm oil would look like under the MSPO scheme, there is no doubt about its sustainability.”

By the end of 2019, two-thirds of Malaysian palm-oil plantations were certified under MSPO. Malaysia is now aiming to ensure that 100 percent of its palm oil is certified by the end of 2020.

Hii does not argue that the MSPO scheme is perfect and has pointed out many important areas for potential improvements. But he also points out that one of the challenges facing the Malaysian government is that it does not directly control land-use policies at a federal level, which are executed by each of the country’s thirteen local states. In particular, the Borneo states of Sarawak and Sabah have even greater say on land-use matters. Other states such as Penang or Perak are poorer and working through different stages of development compared to other parts of the country. These complex internal dynamics create political challenges in the implementation of federally-mandated sustainability policies.

In this context, a major question for Western countries is how they can work with, rather than against, regional countries to support them in creating effective mechanisms to eliminate deforestation.

Of course, in some cases — such as Brazil where the government is brazenly and openly accelerating deforestation — a far stronger approach is required in place of the current policy of abject capitulation and complicity. The question is how to balance this in the form of a more coherent set of policies.

What this means is that a fundamental sea-change is required in the global approach to tackling deforestation, and it requires a new focus on engendering institutions of cooperation rather than competition.

The EU is beginning to wake-up to the failure of its previous approach, but it has yet to come up with a more coherent alternative.

A paper published last month by the European Parliament’s Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union, for instance, admitted that it would be “more effective and less costly” than banning palm oil imports, if major palm-oil producers such as Malaysia and Indonesia were to “implement a moratorium on deforestation.”

What is unclear is what follows from this about-face. Another recent report from the European Parliament’s Committee on Agriculture and Rural Affairs throws some light on this. The report encourages “inclusive partnerships” with the global south to prevent deforestation, but also calls for new legal powers and certification standards that would effectively criminalise deforestation. Yet there is little or no explanation as to how this could work in practice. And the EU still has a very poor understanding of developments on the ground.

At one point, for instance, the Directorate General report dismissed the positive impact of certification schemes in Indonesia and Malaysia based on outdated research. Claiming that “less than one-third of palm-oil production is certified” in these countries, the report concluded that such efforts therefore “fall short of their stated goals”.

While there is no doubt that these schemes require urgent improvement and scaling up, as we have seen above, progress in certification in Malaysia is actually double the EU’s outdated estimate, and the MSPO certification scheme is far more substantive than this document acknowledges.

This gap between perception and reality highlights the real problem in the EU’s approach — a lack of sufficient scientific and diplomatic engagement with key producer countries, especially where progress is being made.

Not only does this lead to an Eurocentric conflation of countries like Indonesia and Malaysia under a single umbrella — which is simply unjustifiable — but it also leads to a fatal lack of understanding of the challenges going on at the local level within such developing nations.

EU parliamentarians and officials need to do more to fill this gap. What is meant by an ‘inclusive partnership’? What kind of legal penalties are proposed and how would they be imposed? How can Europe encourage developing nations to co-operate on common standards of sustainability — especially given its own double-standards on deforestation?

One part of the answer to these questions could be recalibrating trade agreements, or establishing new ones, so that they prioritise mutually agreed ecological standards premised on forest protection and clean energy transition.

For those palm-oil producers which meet environmental standards designed to prevent deforestation, intergovernmental agencies like the UN and the EU along with their most powerful member states should, as an economic carrot, open their markets. For this to work, of course, requires transparent and enforceable conservation and deforestation standards within the respective countries.

To achieve this will require the UN, the EU and others to work closely with countries to develop a joint mechanism for determining rigorous sustainability standards, one that is legally enforceable using national legal powers.

So it is equally important that incentivisation coexists with the prospect of meaningful penalties. Just as there are opportunities for those who meet environmental standards, there should be consequences for those who do not — loss of access to markets, and the suspension of the ability to supply commodities. Such standards should be flexible enough, though, that they encourage compliance in order to obtain a renewal of trade relations rather than intransigence.

The EU’s call for a consistent set of global certification standards in this regard makes sense, but such standards cannot simply be unilaterally imposed from the west, but have to be somehow co-developed with producing countries as partners.

The case of Malaysia could provide a test-case for how such a model might work, with wider implications for EU and western engagement with the developing world. To make real progress, the EU needs to do more to understand, engage with and support the country’s struggle for sustainability.

Malaysia’s federal government is struggling on three fronts — firstly, to empower its MSPO national enforcement capabilities in local provinces which traditionally hold the bulk of legislative land-use powers; secondly, to incentivise smallholder farmers transitioning to mandatory sustainable certification who often perceive it as a major cost-burden; thirdly, to ensure that its standards are as environmentally robust as possible.

All these are areas where a more cooperative approach could open up new opportunities for the EU and other international agencies to provide support to Malaysia in speeding its goal of achieving 100 percent sustainability for palm oil production: financial support for the MSPO programme allocated to local provinces required to implement them, along with further subsidies to smallholder farmers, could be a sound investment; a joint scientific mechanism by which to advance and strengthen MSPO standards would also be important; along with more integrated mechanisms to leverage Malaysia’s recent moves to increase transparency by publishing maps of all palm oil concessions to support better international monitoring efforts.

Success with the MSPO model may well provide a case study of a set of international and national institutional arrangements, policies and legislative instruments which can be used to allow the EU and international agencies to monitor and respond in real-time to the risks of deforestation, while simultaneously working closely with local producers to enforce nationally-backed laws which essentially criminalise deforestation.

Such a model could be scaled-up and applied to other regions, including Africa and South America for instance, where its implementation would, however, require a robust approach from the EU to ensure that countries like Brazil are both pressured and incentivised to fundamentally transform their unsustainable beef production practices.

This would protect the environment, help halt deforestation and benefit European consumers. It would also help the economies of the global south, and support smallholder farmers.

But ultimately, this brings us back full circle. We have addressed the potential for new approaches to tackle deforestation within producer countries. But what about rolling back the industrial consumption machine that is driving the inexorable rise in demand? Is it possible to slow down our overall civilisational trajectory of endless growth, which is the primary reason we are breaching planetary boundaries with abandon?

Escaping the end-game

New cooperative approaches to address deforestation — one symptom of the global crisis of civilisation — are only one sub-set of actions urgently needed for us to change our current course toward accelerating disaster. The other sub-set of actions is related to the deeper drivers of deforestation: industrial civilisation’s insatiable hunger for more.

A question that many of us are increasingly asking ourselves in the midst of the pandemic is — did we really need all this stuff? Do we really need bullshit jobs? Do we really want to keep running on a treadmill?

This question is, too, partly addressed in the Nature Scientific Reports paper which identified the 90 percent risk of civilisation collapsing on our current trajectory of population growth vis-à-vis persistent deforestation.

The paper noted that the main reason the “consumption of the planetary resources may be not perceived as strongly as a mortal danger for the human civilisation” is that modern societies are “driven by Economy”. Such a society “privileges the interest of its components with less or no concern for the whole ecosystem that hosts them.”

To escape our collapse trajectory, the study argues, “we may have to redefine a different model of society, a ‘cultural society’, that in some way privileges the interest of the ecosystem above the individual interest of its components, but eventually in accordance with the overall communal interest.”

In other words, to avert collapse we need a paradigm shift. The good news is that we may be able to avert the worst-case scenario identified in this paper. Just as rates of deforestation appear to be declining — not fast enough and still in extremely tepid fashion — so too are projected rates of population growth.

As a new set of forecasts published by The Lancet suggests, world population may begin to start shrinking after mid-century due to declining fertility rates, rather than continuing to grow as earlier major projections have foretold.

The problem is that minor fluctuations or declines do not dramatically change the model’s baseline prediction of catastrophe within two to four decades.

Although the model’s parameters for population growth and deforestation are constant based on running forward “current conditions”, the study authors point out that “it is hard to imagine, in absence of very strong collective efforts, big changes of these parameters to occur in such time scale” –notwithstanding the possibility of “fluctuations around these trends”.

This underscores the situation we are in. It is not enough for the world’s largest industrial economies to simply point fingers at producer countries and demand action on deforestation. It is also urgently necessary for them to change their priorities in the first place. This means not just looking at legislation to compel ‘Others’ out there to change course while we relentlessly accelerate our own path of endless growth. It also means, therefore, scaling back our complicity in the fundamental drivers of the endless growth machine.

The pandemic is bringing home to us a final lesson. We cannot survive on this planet without sustaining the planetary ecosystems essential for our survival. For life to thrive, it must enable the conditions for life to thrive. If we are intent on destroying the lungs of the earth, then we not only put countless species at risk, we are putting ourselves on the line. If we wish to avoid the next pandemic, climate catastrophe, the biodiversity crisis, if not civilisational collapse, we must do everything we can to save our forests.