The dominant view of the US-led coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS), Operation Inherent Resolve, is that its fundamental goal is the defeat of ISIS.

And so, in the wake of the routing of ISIS from Iraq and Syria, the core justification for an ongoing US military presence in Syria is ensuring that no post-mortem ISIS insurgency arises.

That the US is unequivocally opposed to ISIS is simply taken for granted.

Yet a closer look at the history of US involvement shows that counterterrorism has been a lesser concern relative to geopolitical and strategic goals. Whenever the goals of expanding territorial control or weakening rivals conflicts with the goal of opposing ISIS, the entity was either ignored or even empowered in pursuit of these more paramount concerns.

In some ways, by providing a pretext for extended military operations on foreign soil, and by helping to diminish the military might of the Syrian regime and its allies, some coalition officials have seen the Islamic State as a potentially beneficial phenomenon to the wider ends of weakening the Syrian state and opposing Iranian influence in the Levant.

Leveraging the Caliphate

In 2015, ISIS executed an unprecedented advance in Syria.

Audio leaks would later surface of then Secretary of State John Kerry explaining that the Obama administration saw this expansion as beneficial to the US position.

Seeing that this could be used to pressure Assad, the threat of state-collapse was something to be “watched” and “managed,” rather than deterred. “We were watching,” Kerry said:

“… and we know that this was growing… We saw that Daesh was growing in strength, and we thought Assad was threatened. We thought, however, we could probably manage — that Assad would then negotiate.”

Yet this was not simply a case of exploiting events that were entirely out of control. At this time, Obama’s regional allies had been conducting major influxes of support to jihadist factions among the rebels, including ISIS, for years in their bid to oust Assad.

US intelligence oversaw and was well aware of these policies. As Kerry’s observations suggest, the motive was that with “Daesh growing in strength”, the US military would be able to “manage” this development while the expansion of ISIS would mean that “Assad would then negotiate.”

This all changed when Russia, in response to the expanding ISIS movement, intervened. With Russia in the game, regime-change looked like an increasingly dwindling prospect.

Awkwardly, Russia was “carrying out more sorties in a day in Syria than the US-led coalition has done in a month,” while also targeting ISIS oil tankers, something the US-led coalition was reluctant to do — to the point that large convoys of oil trucks carrying ISIS oil were able to operate efficiently and in broad daylight.

The embarrassing contradictions of the “anti-ISIS” campaign were becoming difficult to explain away. Instead of being “degraded” or “destroyed”, ISIS was actually expanding during the bulk of the anti-ISIS campaign.

Durham University’s Dr. Christopher Davidson, one of the world’s leading scholars in Middle East affairs, has explained that:

“… the Islamic State was effectively on the same side as the West, especially in Syria, and in all its other warzones was certainly in the same camp as the West’s regional allies.”

Moreover, “on a strategic level, its big gains had made it by far the best battlefield asset to those who sought the permanent dismemberment of Syria and the removal of [the Iran-leaning] Nouri Maliki in Iraq.”

Therefore, the trick for the West was “trying to find the right balance between being seen to take action but yet still allowing the Islamic State to prosper.”

Citing a prophetic 2008 RAND Corporation report, Davidson explains that the “illusory campaign that would eventually need to be waged against the Islamic State” would therefore mainly consist of “the establishment of certain red lines” along a “contain and react approach.” This would“involve deploying perimeters around areas where there are concentrations of transnational jihadists,” while making sure to limit any action to only “periodically launching air/missile strikes against high-value targets.”

.jpg)

In other words, Russia’s intervention essentially called Washington’s bluff. Seeing this, and also seeing Syria increasingly in a position to reclaim those territories that ISIS had been so effective at denying them, it appeared that it was time to start getting serious about putting an end to the Caliphate.

Bombing Syria… Again

In terms of its proven effectiveness at weakening the militaries of Syria and Hezbollah, and of draining the resources of Syria’s sponsors, gaining maximum strategic benefit from Islamic State’s eradication would depend not only upon handing over administration of retaken territories to proxies on the ground, but also on ensuring that its guns were primarily being pointed towards Syria and Iran.

While ISIS was indeed fought on certain fronts where it sat upon lucrative energy resources and vital infrastructure, its fighters frequently operated away from allies and toward the front-lines of rivals.

For example, during ISIS’ 2015 surge, whose “threat” towards the Syrian Army (SAA) was to be “managed” by the US as leverage, they successfully encircled and besieged Syrian forces in Deir Ezzor.

Deir Ezzor is important strategically because of its concentration of energy resources, housing the country’s single largest oil deposit, the al-Omar fields.

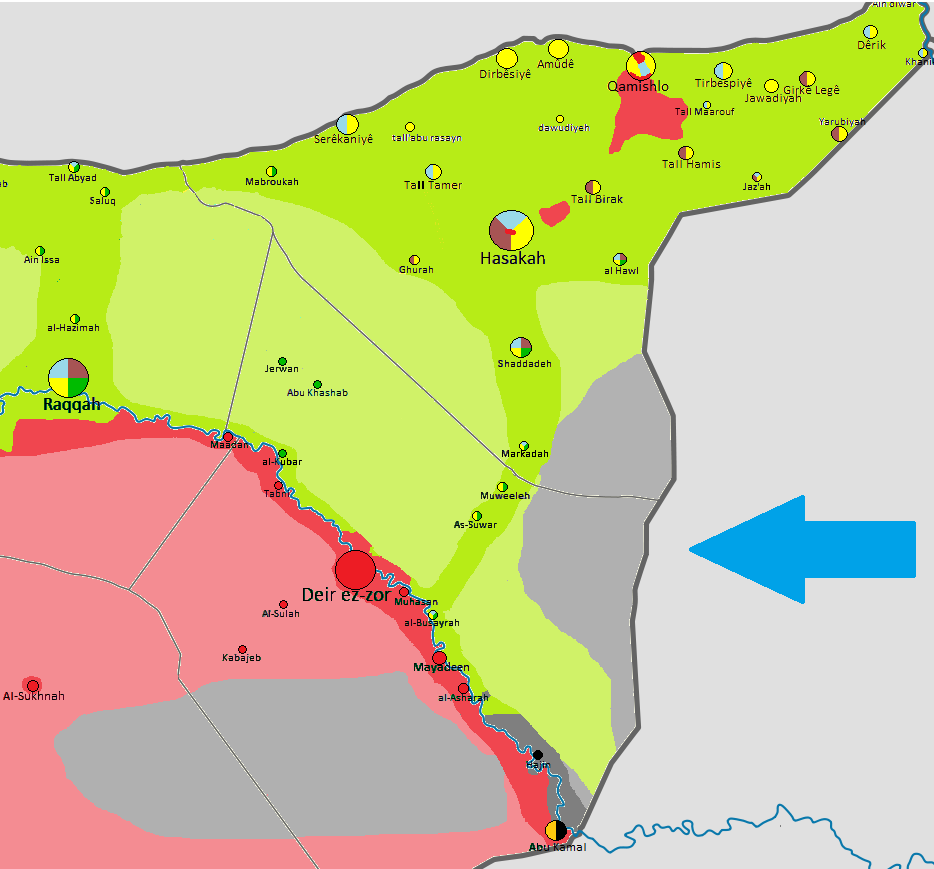

The only effective force fighting ISIS for the West was the Kurdish YPG militias, also called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), who were concentrated along the country’s northern borders. Therefore, the US “sphere-of-influence” that was to be carved from ISIS’ decline was geographically limited to the territory adjacent to this region.

Since the important Deir Ezzor resources were therefore “in-reach”, it was imperative that the Syrian Army did not persevere against the Islamic State and find themselves in a position to take them before the US-backed SDF were able to.

It is perhaps not very surprising that an apparent coalition attack on SAA positions in Deir Ezzor occurred only months after ISIS began besieging the city, killing three soldiers and wounding another thirteen. The US-led coalition bombings effectively assisted the ISIS advance at the expense of Assad’s forces.

While the US vehemently denied responsibility for the attack, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), a pro-opposition monitoring group that receives funding from Western governments, the jets that carried out the attack were “likely to be from the coalition.”

While this could admittedly be chalked up to a one-off mistake, it was not the only attack of its kind.

Almost a year later, as the Syrian government was still holding out against the siege, US-led coalition warplanes launched a much larger and sustained attack, dropping over a dozen airstrikes that reportedly killed dozens of Syrian soldiers while wounding at least a hundred others.

The attack was a major boost to the besieging Islamic State, as one British journalist described it: “in the immediate aftermath, Isis swarmed forward and cut the city in half,” further tightening the noose around the SAA while directly threatening their airborne supply-line.

With the facts this time undeniable, and eager to distance themselves from the obvious strategic advantage received, the US admitted culpability but denied it was anything more than a mistake. The media quickly accepted these denials, overlooking major inconsistencies that remained.

For instance, the official report revealed that the US had misled the Russians about the location of the intended strike, ignored intelligence reports saying Syrian soldiers were being targeted, and circumvented normal targeting procedures before the action was taken, downgrading the intelligence requirements needed to launch the strike.

As veteran journalist Gareth Porter pointed out, the “irregularities in decision-making [were] consistent with a deliberate targeting of Syrian forces.”

Another possible explanation pointed towards the open hostility that top Pentagon officials had expressed towards a joint US-Russia ceasefire deal agreed upon days earlier, which collapsed in the wake of the attack. The officials were specifically antagonistic towards requirements of cooperation with the Russian military, therefore displaying motive and ability.

A further possible explanation was provided by the director of Human Rights Watch. Using language not so different than John Kerry’s, and seemingly in agreement with such a strategy, he wrote on his Twitter handle asking: “As US kills 80 Syrian soldiers, is it sending Assad a signal for his deadly intransigence?”

What is certain is that for those committed to weakening Syria’s progress against ISIS in the much coveted northeastern “sphere-of-influence,” the coalition bombings securely tipped the balance of forces against the Syrian Army, who only managed to survive due to Russian air-power.

The strategic dimension of this is that as long as most of Deir Ezzor was occupied by ISIS, and not Syria, the option to retake it remained open. If Syria reestablished its control, taking the area would not be possible for the US-led coalition without a full declaration of war. Within this political dynamic then, the only way to make sure that the area remained “in-reach” of the coalition was by ensuring that the Islamic State remained in control and prevented further Syrian expansion.

And while conventional pundits would routinely dismiss the occurrence of such strategic considerations, they plainly did take place.

The US defense establishment thought-process was best described by the former director of the CIA, Michael Morell. Echoing Kerry’s mindset, Morell said the United States needed “to make the Iranians pay a price in Syria, we need to make the Russians pay a price,” specifically advocating the killing of Iranians and Russians operating in the country to do so. “I want to put pressure on [Assad],” he continued, “I want to put pressure on the Iranians, I want to put pressure on the Russians,” in order to make them “come to that diplomatic settlement.” Importantly, however, this was to be done “covertly,” he said, “so you don’t tell the world about it, right? You don’t stand up at the Pentagon and say, ‘we did this,’ but you make sure they know it in Moscow and Tehran.”

Indeed, these were the very possibilities being discussed among the highest policy-planning bodies within the administration.

John Kerry himself requested on multiple occasions that the US launch missiles at “specific regime targets”, in order to “send a message” to Assad to “negotiate peace.” Like Morell, Kerry suggested the US would not have to acknowledge the attacks, but that Assad “would surely know the missiles’ return address”.

Live to Fight Another Day

The strategic benefits afforded from ISIS were perhaps best described by Thomas Friedman. Writing in the New York Times, he explained that:

“America’s goal in Syria is to create enough pressure on Assad, Russia, Iran and Hezbollah so they will negotiate a power-sharing accord… that would also ease Assad out of power.”

Therefore, since the Islamic States’ “goal is to defeat Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria — plus its Russian, Iranian and Hezbollah allies… we could simply back off fighting territorial ISIS in Syria and make it entirely a problem for Iran, Russia, Hezbollah and Assad.”

His assessment was that the US did not want to defeat ISIS straight away, because “if we defeat territorial ISIS in Syria now, we will only reduce the pressure on Assad, Iran, Russia and Hezbollah.”

One way was to leave an open corridor for ISIS fighters to escape through, in areas where US-backed forces were battling the group.

This under-reported aspect of Obama’s official policy toward ISIS has quietly been kept in place during the Trump administration.

Prior to the battle in Mosul, top ISIS leaders were reportedly able to flee the city and find their way into Syria. As the battle was waged, regular ISIS units also apparently had open access to a similar escape route.

Sources described seeing hundreds of fighters fleeing Mosul and entering into Syria, heading towards Deir Ezzor and Raqqa. The strategic rationale was alluded to by Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, when he told the media “if Daesh were forced out of Mosul, they were likely to go on to Syria.”

The Iraqi commander in charge of the operation would confirm that this indeed had happened. Citing intelligence information he received, the commander said that militants “were fleeing Mosul to Syria along with their families.”

Not long after this, ISIS launched an offensive in Deir Ezzor. The Guardian reported that the fighters breaking through government defenses were “primarily reinforcements coming over the border from Iraq’s Anbar province,” who then “broke through government lines, splitting its territory in half and taking control of the area where the WFP’s [World Food Program] airdrops landed.”

A year later, now during President Trump’s administration, the campaign against ISIS in Tal Afar, Iraq, ended in little over a week. Heralded as a testament to the strength of ISIS’ enemies, it soon became clear that the victory was only made possible by a major ISIS retreat.

In a direct reference to the ‘open corridor’ policy, the Iraqi commander helming the battle told reporters that “significant numbers of fighters were able to slip through a security cordon” and escape. More worryingly, this was made possible because “There was an agreement” with ISIS, according to Major General Najim al-Jobori, between the militant group and Iraqi Kurdish forces. Some of those retreating turned themselves in, while others “fled to Turkey and Syria.”

The report is notable given evidence, previously reported by INSURGE, that elements of Iraqi Kurdish authorities had ties to ISIS in relation to the facilitation of oil sales.

Later in Syria, the situation came to a head when the Syrian Army marched eastward and finally broke the three-year-long siege in Deir Ezzor, placing the surrounding oil-fields within their reach at a time when the US-backed SDF were also marching closer.

The New York Times would describe how “a complex confrontation is unfolding, with far more geopolitical import and risk…

“The Islamic State is expected to make its last stand not in Raqqa but in an area that encompasses the borders with Iraq and Jordan and much of Syria’s modest oil reserves, making it important in stabilizing Syria and influencing its neighboring countries. Whoever lays claim to the sparsely populated area in this 21st-century version of the Great Game not only will take credit for seizing what is likely to be the Islamic State’s last patch of a territorial caliphate in Syria, but also will play an important role in determining Syria’s future and the postwar dynamics of the region.”

It was within this context that another agreement was struck ending the battle for Raqqa. The SOHR said it:

“… received information from Knowledgeable and independent sources confirming reaching a deal between the International Coalition and the Syria Democratic Forces in one hand; and the ‘Islamic State’ organization in the other hand, and the deal stated the exit of the remaining members of the ‘Islamic State’ organization out of Al-Raqqah city.”

The SOHR “confirms that this agreement has happened.”

It was later revealed that the agreement included some 50 trucks, 13 buses, 4,000 evacuees and all of the fighters’ weapons and ammunition.

Further information came to light when a high-level participant in the negotiations blew the whistle.

Brigadier General Talal Silo, a former SDF commander who acted as the spokesman for the US’ leading partner in the fight against ISIS, and who has since defected to Turkey, explained that an “agreement was reached for the terrorists to leave, about 4,000 people, them and their families,” all but five-hundred of whom were fighters. He said that a US official had “approved the deal at a meeting with an SDF commander.”

Even more damning, and apparently confirming that specific end-destinations were included within these kinds of agreements, the commander:

“… came back with the agreement of the US administration for those terrorists to head to Deir al-Zor.”

The ISIS evacuees protected under the US-approved agreement were to head towards ISIS-controlled areas “where the Syrian army and forces supporting President Bashar al-Assad were gaining ground.” Here, they would “prevent the regimes advance.” The BBC corroborated this, tracking the convoy to one of these very areas.

Reuters also reported that the front being fought by the Syrian government in Deir Ezzor had “turned into a major base for Daesh militants after the US-backed offensive drove them out of Raqqa.” The deal, in short, directly “boosted the US fight against the forces of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad,” as Newsweek observed.

“According to the Americans,” Brig. Gen. Silo continued, “the regime army could reach Deir ez-Zor in six weeks” at first, “but when the regime army proceeded faster than expected, the US wanted the SDF to begin negotiations with Daesh.” The deal was then endorsed because the US “wanted a swift end to the Raqqa battle so the SDF could move on towards Deir al-Zor.”

Silo also claimed that the US and the SDF had made similar deals on at least 2 other occasions, corroborating a Syrian dissident and human rights activist who earlier claimed that a similar agreement had been reached during the battle for Mosul.

In terms of providing “a swift end to the Raqqa battle” and allowing the SDF to “move on towards Deir Ezzor”, the US-brokered deal proved a success. Just days later the SDF captured the al-Omar fields, the largest and most lucrative Syrian oil deposit.

But according to Elijah Magnier, journalist and war correspondent for the Kuwait-based Al Rai newspaper, after “the United States preceded Russia to the oil and gas Omar oilfield… ISIS then delivered [it] to the Kurds without any resistance.”

Validate this, an SDF spokesperson described how “our forces managed to liberate the fields without notable damages.”

Indeed, according to the SOHR, the “advancement achieved by the Syria Democratic Forces, in which they entered Al-Omar oilfield and took the control of it,” had occurred only “after a counter attack by ISIS [against the SAA], that kept the regime forces away of the outskirts and the vicinity of the field.” It was a tight race though, as “government forces were 2 miles away from the fields” at the time.

The remaining oil-fields and surrounding countryside east of the Euphrates were swept up by the SDF along similar lines, with ISIS voluntarily agreeing to evacuate the areas. SOHR’s sources further clarified “that ISIS prefer[s] handing over the organization-held areas to the SDF instead of handing them over to ‘the Shiite Militia’, in order to prevent the regime forces from advancing towards these area[s].”

As Elijah Magnier reported at the time that:

“US-backed forces advanced in north-eastern areas under ISIS control, with little or no military engagement: ISIS pulled out from more than 28 villages and oil and gas fields east of the Euphrates River, surrendering these to the Kurdish-US forces following an understanding these reached with the terrorist group.”

Furthermore, “this deal was an effective way to prevent the control by the Syrian army” given that “the United States seems determined to hold on to part of the Syrian territory, allowing the Syrian Kurds to control northeast Syria, especially those areas rich in oil and gas.”

Protecting the Pretext

The lines between Russia and the United States were therefore cut in two by the Euphrates; the SDF to the east, the Syrian Army to the west.

As ISIS’ Caliphate reached its final demise, the US established new rules of engagement, announcing it would not allow Syria or its allies to cross into its zone of control.

The US also announced it would continue its occupation of northeastern Syria indefinitely, even after ISIS is gone. The US currently has at least ten small scale military bases set up within the country.

The overall strategy, according to an analysis by Joshua Landis, a highly-regarded Syria expert and professor at the University of Oklahoma, is aimed at thwarting economic recovery and interconnection within the region, in an attempt “to hurt Iran and Assad.”

The United States’ “main instrument in gaining leverage,” Landis said, are “the Syrian Democratic Forces” and the areas they have conquered in “Northern Syria.” By “denying the Damascus access to North Syria” and by “controlling half of Syria’s energy resources, the Euphrates dam at Tabqa, as well as much of Syria’s best agricultural land, the US will be able to keep Syria poor and under-resourced…

“Keeping Syria poor and unable to finance reconstruction suits short-term US objectives because it protects Israel and will serve as a drain on Iranian resources, on which Syria must rely as it struggles to reestablish state services and rebuild as the war winds down.”

Therefore, by “promoting Kurdish nationalism in Syria,” the US “hopes to deny Iran and Russia the fruits of their victory,” while “keeping Damascus weak and divided.” The US position “serves no purpose other than to stop trade and prohibit a possible land route from Iran to Lebanon,” and to “beggar Assad and keep Syria divided, weak and poor.”

Yet with such an approach in mind, the defeat of ISIS posed a dilemma.

Battling ISIS was the fig leaf under international law that the US relied on to legitimize its military operations on foreign soil without Syria’s consent. With ISIS gone, even this shaky argument does not hold. The US administration was therefore caught between a rock and a hard place.

It is perhaps not a surprise then that the US has, for months, been effectively safeguarding an ISIS contingent pocketed within SDF controlled areas along the northern border with Iraq.

Indeed, the official OIR reports register that virtually no airstrikes have been conducted in this area since at least mid-November 2017, only elsewhere along the eastern banks of the Euphrates, “near Abu Kamal” (see here for easier viewing).

By preventing Russia and Syria from crossing the Euphrates to finish fighting ISIS, and by refusing to attack it in these areas, the US presence has essentially protected the Islamic State from a full territorial defeat in Syria.

In that sense, it is extremely worrying that Defense Secretary Mattis has told reporters that the US will plan to stay in Syria and “keep fighting as long as they [ISIS] want to fight,” because “the enemy hasn’t declared that they’re done with the area yet.”

There is also another incentive. Much like the ‘open corridor’ policy, the US has announced “it will not carry out strikes against the militants’ last remaining fighters as they move into areas held by the Assad regime in western Syria.”

This has prompted even US-backed opposition fighters to suspect that:

“… their own side could be allowing small Isis pockets to survive so they can attack and weaken the regime and its main backer in the region, Iran.”

In closing, all of these polices have in one way or another been justified under the need to “protect civilians.”

Yet even within the bounds of official narratives, even if all of what has been presented here is disregarded, this is still problematic, given what Charles J. Dunlap Jr., professor of law at Duke University, has called “the moral hazard of inaction.” Since the end result of these US policies allows ISIS to survive, the notion that they “save civilians” isn’t really valid, since “the ISIS fighters who might have been killed lived on to butcher civilians” at a later time.

Unfortunately, thanks to the evolution of US military strategy, ISIS will continue to have the opportunity to do so.