Anyone paying attention to popular culture trends in the West often disregard the messages that aim to shape political opinions of young people, whether this is through Hollywood or the gaming industry, TV shows or music. If the children that we know personally tend to have good mental health and carry a sufficient sense of self-awareness and emotional intelligence, then we’ll generally regard this messaging as innocuous. We would reserve more careful judgement for when these messages might influence vulnerable young people. But the problem with this is it has made us much less vigilant.

New efforts ostensibly intended to inform young people of the dangers of fake news and misinformation are increasing in line with collective Western attempts to contain Russia and China’s growing influence. However well-intentioned they are, even a cursory look at these efforts reveals they are promoting confirmation bias: their content ranges from mild propagandistic messaging to full-blown jingoistic deception. They have made it easy for critics to anticipate a process that will look subjectively instructional rather than objectively educational.

The BBC launched their iReporter game earlier this month. On March 15th it was received positively while news of the initiative spread online. We were told it aims to educate young people on “the dangers of Fake News” and predictably the mainstream reports welcomed this without any scepticism, and without a definition of what fake news actually is:

indy100.com: “Which sources should you trust? How quickly should you break the story with limited facts? And how are you going to do all this and keep your editor happy?”

belfasttelegraph.co.uk: “…led by the broadcaster called School Report, which also offers workshops and events featuring BBC journalists, including Huw Edwards.”

gizmodo.co.uk: “…designed for kids and their teachers, in an effort to show how to recognise which sources can be trusted and which ones are complete nonsense.”

huffingtonpost.co.za: “Fake news has become a problem over which both governments and social media companies have had to step in and take action.”

I have asked in a previous piece— which examines the meme of fake news — that if the dangers of misinformation are so great as to warrant legislation which can threaten our freedom of speech and right to privacy, then should not every article that sets out to inform us about misinformation do that task more rigorously?

As outlined in the mainstream’s stenography journalism, the game is part of larger initiative called the BBC School Report national programme to help 11–18 year olds identify fake news; and, they claim, to develop “critical thinking and media literacy skills” in young people. BBC cited A National Literacy Trust report which details (deep breath): the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Literacy’s launch of the Commission on Fake News and the Teaching of Critical Literacy Skills in Schools. Their claim is that one in five children believe everything they read online is true.

And so primary and secondary school teachers will be entrusted with leading new initiatives because they are described as “ideally placed” to help children develop the skills they need. I’d suggest that parents should hope the teachers will be open to refining their own critical literacy skills in the process. The director of the trust, Jonathan Douglas, had this to say:

“In this digital age, children who can’t question and determine the reliability of the information they find online will be hamstrung — at school, at work and in life […] By bringing together the greatest minds and authorities on fake news and education, the new parliamentary commission gives us a fantastic opportunity to make the case for critical literacy to sit at the heart of our education system.”

This is a very serious matter, so much that the greatest minds and authorities on fake news must be enlisted to help the children. I can’t argue with the case for critical literacy to sit at the heart of an education system, but how might one determine who the greatest minds and authorities on fake news are? I’d suspect it would be those who propagate the notion that fake news is a profound threat to our Western democracies. In which case we can rest assured that the children will indeed be guided by those with authority — how great their minds are, though, would remain to be seen.

Try not to question authority

Why should I not add to the praise of the BBC? Well my first thought was how interesting it is that there never seemed to be a threat to children from fake news until now — over a year after Brexit and the election of Trump.

So after getting some tips from BBC professionals in a series of trendy videos under the section on how to to spot fake news, I went on to try the iReporter game. But I could not share the enthusiasm others have for it.

The immersive online game was designed by Aardman studios and convincingly presents a high-pressure and deadline-driven environment in which the player must judge the reliability of information about stories before publishing to online BBC platforms. Students are scored on accuracy, impact, and speed.

Having many years experience working in deadline-driven design and publishing offices, the overall impression that struck me, and has stayed with me, was the aspect of the fast pace. The player has very little time in which to think critically about their choices.

What’s interesting about this is how common it is in the creative and media industries — early on when you start in a professional career — to realise that you feel unprepared for the reality of multitasking in fast-paced, deadline-driven environments. In general, it’s fair to say that university (and even work experience/internships) can rarely prepare a student for that moment when they need to hit the ground running.

It can be as terrifying as it is exhilarating to work on an assignment with an important deadline that can not be extended based on personal mitigating circumstances.

So it struck me that — before the students engage in careful consideration and discussion on the topic, before the rational part of a teen’s brain is fully developed — when tasked with introducing children to critical thinking and media literacy, they place the student in a simulation of a work day that in reality can take a young adult years to get to grips with. One which you are under high pressure to make right decisions.

Although my next point may not seem relevant to a school lesson, it’s an important one that is implied by the nature of the game: if the simulation was accurate then reactions from editorial staff to mistakes would certainly not be as tolerant and lighthearted as portrayed. In striving for realism, the creators know this takes away from it — children will associate mistakes and low scoring on the game with a possibility of being reprimanded in a real life situation, therefore avoiding mistakes is what motivates you to succeed.

At this point, noticing how they’ve taken advantage of games-based competitiveness in children, I could delve into such subjects as conditioning and behaviorism, but I’ll leave that for people more qualified myself. Though I would go as far as to suggest this seems comparable with the link between gaming and military recruitment.

Overall it seems to me that this is remarkably counterproductive if what we’re dealing with is an introduction to thinking that is critical.

Is there an ulterior motive to the format of the game? One which the student isn’t encouraged to think critically about? The medium, it seems, is not part of this message. Because when their concern stems from the changing media landscape, in which we get information from a much wider range of sources — and young people are not helped to think about the wider range of sources, to carefully asses them with a view to finding some of them a positive development — the suggestion is to associate new sources with false information, persuading the student to reject them outright.

In this situation, from what I can tell, they are equating critical thinking with a responsibility to an editorial board to make a right decision, instead of a wrong decision, under intense pressure.

What you would hope a student takes away from this is an ability to step back and question on many levels why one decision was accepted over another, beyond the theme that certain sources are supposedly unreliable, but that might not be one of the intended outcomes of iReporter.

‘Toxic’ Putin on mission to poison the West

The Day is a daily news service for schools and colleges with the tagline ‘news to open minds’— it’s difficult to navigate their crowded site and learn clearly what their mission statement is, how intentional this is I can’t be sure. It seems to be quite a substantial operation run by former editor of the Daily Express Richard Addis.

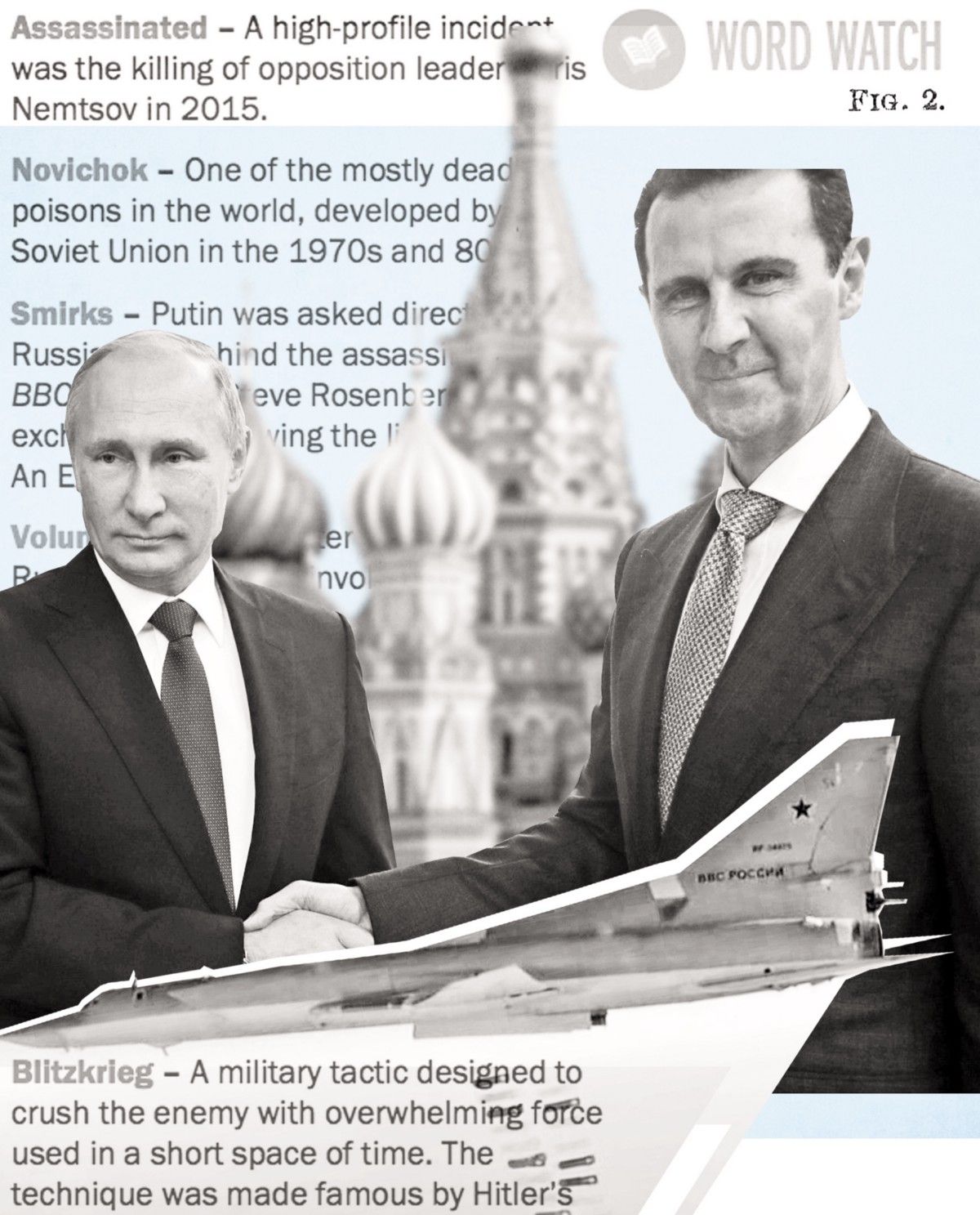

There are many projects on the website where articles are used for lessons, homework, and research. On March 16th they published a tutorial/activity called ‘Toxic’ Putin on mission to poison the West.

The project asks: “Is Putin the most dangerous man in the world?” It goes on to request: “As a class list all of the facts you know about Russia. Do you think Russia is a misunderstood country? Why, or why not? What impression does Putin give about what Russia is like?” And finally to discuss if the West worries too much about Putin.

It includes a Q&A on the Skripal case and a section called ‘Become An Expert’ in which you’re told you can “get a sense of different viewpoints” from such (non-diverse) platforms as BBC News, Vox Media, The Financial Times, and The Spectator.

With a few more and varied sources to base your research around, all this would be fine for a class lesson —if the entirety of the preceding introduction had not been filled with Anti-Russian talking points.

It says about various accusations leveled at Putin that despite “incriminating evidence and international outrage, Putin merely smirks and denies everything.” Later it quotes Owen Matthews as stating that Russia’s casual denial of involvement is an “assault on the very idea that truth itself can exist.”

This surely puts a strain on a task where students seek evidence that Putin might not be the most dangerous man in the world.

Especially when they say he “sits on stockpiles of nuclear warheads and chemical weapons” and has “invaded Crimea” in “the first forcible land grab in Europe since 1945.” And he’s implicated in a “digital blitzkrieg of cyberattacks” and the “destruction of a Malaysian Airways plane killing 298.”

And so without making any case for him potentially not being the most dangerous leader since Hitler, it concludes the intro with:

“Russia has invaded sovereign nations, tried to destabilise liberal democracies, and been implicated in violent assassinations — all on Putin’s watch. Throw in nuclear brinkmanship and the fostering of violent Russian nationalism, and Putin undoubtedly resembles one of Europe’s greatest threats.”

The student’s must be bewildered, thinking that this isn’t much of a test because the answers seem pretty obvious. It’s clear what those devising the test believe the answers should be given they left impartiality aside.

Fundamentally, assigning a task where both sides must be considered, it does not mention anywhere that many people believe: Russia is helping to bring stability to Syria with its counter-terrorism operation there. That Putin rebuilt and modernised the country after the rape of Russia in the 1990s was facilitated by the West under Boris Yeltsin, who was put in power with help from Washington. That Crimea had a referendum voting to rejoin Russia after the US orchestrated the violent coup in Ukraine, during which they armed neo-Nazi groups. That the extent to which Russia is surrounded by US and NATO military hardware and personnel, and NATO moving eastward to its border after it was agreed that it would not, might have led the supposed aggression from Russia. And it does not mention any long term implications of the US pulling out of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002.

Are all of these games, tests, and workshops being engineered to help safeguard the British establishment by reducing the numbers of potential future dissidents? Do they hope that less future government employees will leave their positions to become whistle-blowers, and that fewer mainstream journalists will become disillusioned and leave to join independent media platforms?

March Madness

March 2018 has unfolded with the most frenetic succession of events. It has been shaped by a dangerous anti-Russian sentiment shared by Western countries, and the British Parliament has been at ground zero of this.

We’re seeing a continuation of the Western establishment system’s use of the fake news meme as a way to marginalise independent and alternative media sources of almost all kinds. The derision and suppression of Western dissident writers opposing establishment narratives continues unquestioned by mainstream press.

Events included the fallout from the SCL/Cambridge Analytica story, and March For Our Lives in the US. But the collective expulsion of Russian diplomats from the US and EU stood out most strongly and will have long-lasting repercussions. This was marked by the same Western liberal order that abhorred the rise of Trump and Brexit’s alleged xenophobia display a shameful act of hostility to Russian people at a time when they were coming to terms with the Kemerovo tragedy.

A “show of support” for the UK — over their finding of guilty by conjecture, during an ongoing investigation without disclosure of full information — should have instead been a “show of support” for Russians in their time of mourning.

The month is coming to a close with ramping up of the ‘Russian aggression’ myth. As usual little to nothing will be made of aggression that comes from NATO. This week saw the launch of Britain’s counter-propaganda war against Russia as Theresa May’s ominous sounding ‘Fusion Doctrine’ defence plan was unveiled.

In reporting on this, the Telegraph (paywall) cited security sources as saying that to protect the West from Russia, North Korea, and terrorist groups, a social media counter propaganda strategy should be:

“suffocating hashtags on Twitter”

A day earlier the Telegraph told us that BBC journalists will teach children about fake news. The article was scant on details or relevant links but the scheme is connected to the above-mentioned BBC initiative.

They say “BBC journalists are to visit schools to teach children how to identify fake news.” That it will involve up to 1000 schools and includes BBC journalists “such as Huw Edwards, Tina Daheley, Nikki Fox, Kamal Ahmed and Amol Rajan.” More on this was outlined in Wednesday’s BBC annual plan.

Will BBC journalists teach school children about the Western establishment’s practices of “suffocating” information that it doesn’t like online?

How about children help BBC journalists with media literacy

The very same day on which positive news of BBC’s iReporter game spread online, BBC News published a piece marking the anniversary of the start of the conflict in Syria which they describe as civil war. The lengthy and detailed piece is titled Why is there a war in Syria?

If the students are adequately taught about the dangers of trusting questionable sources, then a visit from BBC journalists — such as those who put together a piece claiming to answer definitively why there is war in Syria — would offer them an opportunity to challenge the BBC on their supposedly authoritative claims.

The piece is filled with information graphics, statistics, and the usual one-sided details which inevitably muddy the waters instead of giving a clear picture of events.

Hypothetically, the children could turn the tables on visiting BBC journalists. The school children could ask the journalists about how trustworthy the “network of sources on the ground” are with which the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights documented “the deaths of 353,900” people. Similarly they could ask them about the much-disputed information and footage that the BBC broadcasts from groups like the White Helmets:

The piece would offer a lot of scope for students to take the journalists to task. They could ask why journalists don’t talk to the large numbers of people who have been freed from terrorist captivity by pro-Assad government forces, people that might have a different perspective on events. But of particular interest could be an examination of the opening line of the article:

“A peaceful uprising against the president of Syria seven years ago has turned into a full-scale civil war.”

After disputing calling it a civil war, rather than a carefully orchestrated invasion conducted by foreign nation states, the students could further dispute the BBC’s claim that the cause of the war grew out of a peaceful uprising. They could start this by asking if a source like Syrian American journalist Steven Sahiounie is trustworthy, because they discovered that he had said this about the uprising:

“In reality, the uprising in Deraa in March 2011 was not fueled by graffiti written by teenagers, and there were no disgruntled parents demanding their children to be freed. This was part of the Hollywood style script written by skilled CIA agents, who had been given a mission: to destroy Syria for the purpose of regime change. Deraa was only Act 1: Scene 1.”

If the BBC journalists were not convinced by this source, perhaps telling the school children that they risk becoming conspiracy theorists, then the students could go on to quote a detailed article by writer and political activist Stephen Gowans called The Revolutionary Distemper in Syria That Wasn’t. It outlined the lack of popular support for the protests with this information:

“That the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood played a key role in the uprising that erupted three months later was confirmed in 2012 by the US Defense Intelligence Agency. A leaked report from the agency said that the insurgency was sectarian and led by the Muslim Brotherhood and Al-Qaeda in Iraq, the forerunner of Islamic State. The report went on to say that the insurgents were supported by the West, Arab Gulf oil monarchies and Turkey. The analysis correctly predicted the establishment of a “Salafist principality,” an Islamic state, in Eastern Syria, noting that this was desired by the insurgency’s foreign backers, who wanted to see the secular Arab nationalists isolated and cut-off from Iran.”

If this was to cause some consternation among the journalists they might continue pushing the conspiracy theorist line. At which point the students could present them with the document mentioned in the article, and ask them to study it carefully before commenting further.

Before sending the illustrious BBC journalists on their way, students could ask about the roles played by the British and their good friends the Saudis in the Syrian crisis.

And question them about a detailed analysis done on their 2013 Panorama documentary ‘Saving Syria’s Children’ in which it has been claimed the aftermath of a bomb attack is “largely, if not entirely, staged.”

Finally, they could end the session by asking them what sort of activities their colleagues from BBC Media Action were involved in when working to advise Syrians to challenge their national government long before the “peaceful uprising” began.

With these initiatives, devised allegedly to equip students with critical thinking and media literacy skills, it’s clear that there are established narratives one must remain in agreement with. They are not designed to provide school children with the ability to comprehensively question all institutions including the BBC. To subject mainstream corporate and state media to the same criticisms as directed at sources found across social media and independent media.

Or will the people behind all of this be open to answering challenging questions from the students? If your children are not lucky enough to be absent on the day that BBC journalists turn up, then hopefully you will have prepared them to ask if it’s possible for media malpractice to happen at the BBC, as well as all other major news organisations. They could quote the Editors’ Code of Practice to the journalists:

“The Press must take care not to publish inaccurate, misleading or distorted information or images, including headlines not supported by the text.”