The world is convulsing — wars, climate shocks, collapsing trust in politics and media. For Cambridge historian Christopher Clark, writing in Foreign Policy, this is the “end of modernity.” Multipolar geopolitics, disinformation, climate disruption: the grand narrative of progress dissolving.

But that diagnosis only scratches the surface. What’s ending is not just modernity as an idea. It is the life-cycle of industrial civilisation itself. We have entered the back loop of the planetary phase shift — the stage of release and reorganisation, where brittle structures collapse and new possibilities emerge. The choice before us is stark: collapse or renewal.

And here lies the deeper tragedy. Most of the experts and commentators we rely on to make sense of the world are blind to this reality. They catalogue symptoms but miss the drivers. They narrate the noise of events while ignoring the deeper systems that shape them. Their myopia is itself part of the crisis.

When I read Christopher Clark’s essay in Foreign Policy, “The End of Modernity”, I recognised a familiar unease. He captures something essential about our moment: the sense that the old stories which once ordered our world — of progress, growth, democracy, and stability — are dissolving. Institutions are fracturing, alliances faltering, and the media landscape has collapsed into noise. And hanging over it all, as Clark rightly notes, is the spectre of climate change, “looming like a threatening storm cloud.”

But while Clark sees clearly that something profound is ending, he mistakes what it is. He calls it the death of “modernity.” I see something even deeper: not just the collapse of an idea, but the unravelling of an entire civilisational life-cycle.

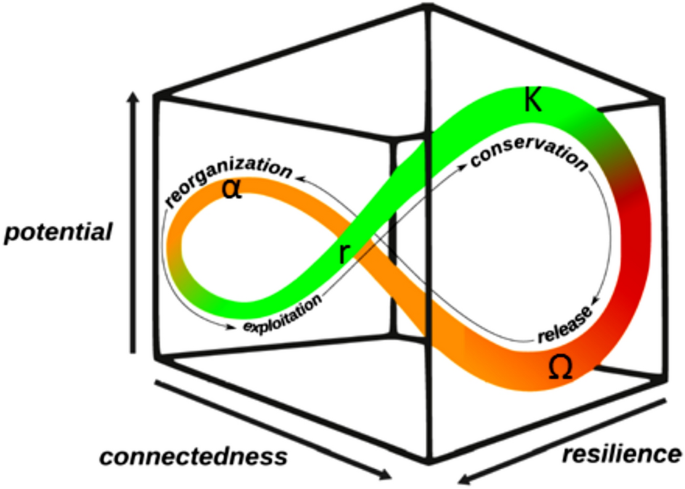

To explain this, I draw on what I call the planetary phase shift. It’s a way of understanding human civilisation as a complex living system that — like an organism, a forest, or even the Earth’s climate — moves through distinct stages of growth, stability, breakdown, and renewal. This idea comes from the work of ecologist C.S. Holling, who studied how ecosystems like forests evolve over time. He noticed that systems don’t grow forever. They expand rapidly by exploiting resources, then settle into a period of stability and conservation. But that stability eventually breeds rigidity: when shocks hit, the system can no longer adapt. It collapses into a phase of breakdown, releasing energy and material, before reorganising into something new (Ahmed 2024, p.3).

Holling called this pattern the adaptive cycle. The front loop is growth and conservation — the era of expansion and stability. The back loop is release and reorganisation — the era of breakdown and transformation. Every living system, from a forest to a human society, moves through this cycle in a process driven by fundamental thermodynamics.

Seen through this lens, industrial civilisation — the fossil-fuel powered, growth-obsessed system we live in — is not just in crisis. It is entering the back loop of the adaptive cycle: the phase of release and reorganisation. What Clark describes as the “end of modernity” is really this: the end of a life-cycle. The breakdown of political institutions, the fracturing of media, the rise of multipolar disorder — these are the characteristic symptoms of a civilisation moving through the release phase.

And here is the crucial point: breakdown is not the end. In the back loop, collapse and renewal happen together. The same dynamics that cause disruption also create openings for new possibilities. That is why I prefer to talk not of the “end of modernity,” but of a planetary phase shift: a systemic transformation of human civilisation on a global scale, driven by the interplay of environmental shocks, energy and technology transitions, and the breakdown of our prevailing organising systems (Ahmed 2024, p.4).

Want deeper insights? Get access to detailed macrointelligence, scientific white papers, and investor briefings by subscribing to premium...

What Clark Gets Right

Clark’s instincts are not wrong. If we take his essay as a map of the surface of our moment, it is an accurate sketch of the turbulence we can all see and feel. He points to three major features: the emergence of a multipolar world, the collapse of trusted information systems, and the encroaching shadow of climate change. Each of these is real. But they are symptoms. They are what a civilisation looks like when it is tipping out of equilibrium.

Multipolarity and geopolitical turbulence

Clark is right that the familiar architecture of international order is coming apart. The Cold War gave us a strange kind of stability: two superpowers locked in rivalry, each defining the other, each setting limits that prevented total breakdown. After 1989, for a brief moment, it seemed that the United States could stabilise the world in its image. But as Clark notes, that moment has passed. The rise of China, the resurgence of Russia, and the assertiveness of regional powers like Turkey have ushered in a multipolar world, fluid and unpredictable.

From the perspective of planetary phase shift, this turbulence is what we expect in the release phase of the adaptive cycle. Just as a forest, once overgrown, becomes brittle and vulnerable to fire, so too do political orders built on rigid hierarchies become brittle when external shocks mount. Multipolarity is not the cause of this disorder; it is its outward expression (Ahmed 2024, p.4).

Information disorder and the collapse of shared meaning

Clark also observes the collapse of what he calls “modern mediatization.” In the modern era, newspapers, radio, and television served as anchor institutions, shaping collective identities and providing common reference points. Today, those anchors have disintegrated. Information flows through fragmented networks where rumour, outrage, and manipulation often spread faster than fact.

Again, this is precisely what happens in the back loop of the adaptive cycle. Breakdown in a civilisation’s information-processing systems is a hallmark of systemic release. As shocks multiply, societies lose their ability to distinguish signal from noise. Polarisation intensifies. Shared narratives splinter. The system’s capacity for collective sense-making deteriorates (Ahmed 2024, p.9).

This dynamic is illustrated in what I call the collapse feedback loop. Environmental shocks — Earth System Disruption (ESD) — cascade into political and social upheaval — Human System Destabilisation (HSD). As societies focus on symptoms rather than root causes, they polarise further, undermining their capacity to respond, which in turn intensifies the original shocks. Clark’s “gossipmongers of the internet” are one face of this deeper feedback dynamic.

Climate as the storm cloud

Most importantly, Clark recognises that climate is not just another issue alongside others, but the existential horizon hanging over all. He describes it as a “storm cloud,” threatening to erase the very possibility of a future.

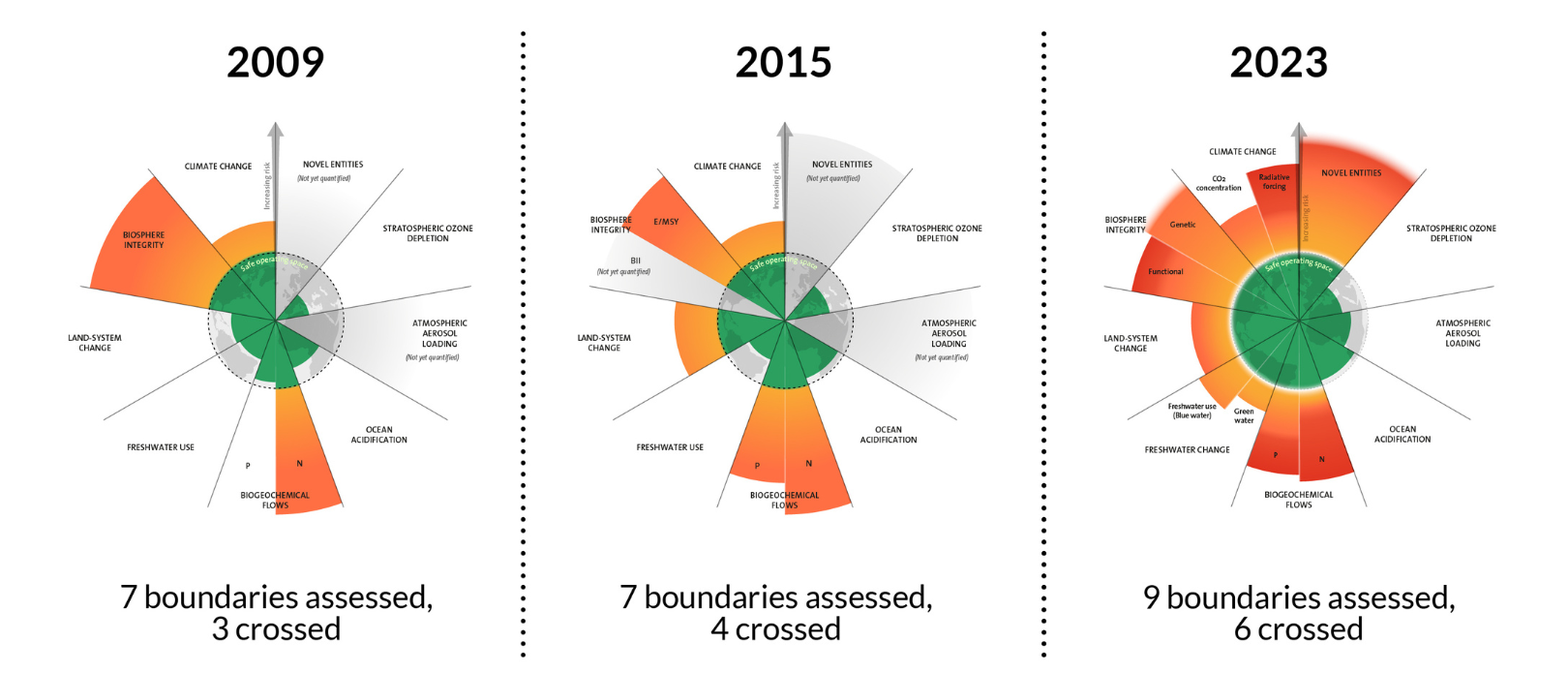

Here again, he touches the reality but does not grasp its depth. Climate disruption is not merely a challenge that overshadows politics. It is the material foundation of our crisis. The science of planetary boundaries shows that human activity has already destabilised critical Earth system processes: climate, biodiversity, land use, and nitrogen cycles, among others. These boundaries define the safe operating space within which human civilisation can thrive. Breaching them threatens the stability of the Earth system itself.

What Clark senses as the “end of modernity” is in fact the manifestation of a deeper process: civilisation crossing thresholds in the Earth system that force it into the back loop of release and reorganisation. Multipolarity, information collapse, and climate disruption are the surface expressions of a civilisation that has outgrown its current form, and is now unravelling into something else.

What Clark Misses

Clark’s essay is sharp in tracing the disintegration of “modernity.” But it leaves the most important question unasked: why is this happening now? Why, after centuries of expansion and progress, do our institutions suddenly seem so fragile? Why do the grand narratives of growth and democracy no longer hold? And why is climate no longer a distant concern, but a lived destabilisation?

The answer lies in the metabolism of civilisation itself — the flows of energy and resources that sustain it. Modernity was never just an idea. It was a material system, powered by fossil fuels. For two centuries, coal, oil, and gas delivered vast surpluses of cheap, high-quality energy. That energy surplus is what underwrote industrial growth, welfare states, scientific progress, and geopolitical stability.

But here is the turning point: that energy surplus has been in decline for decades.

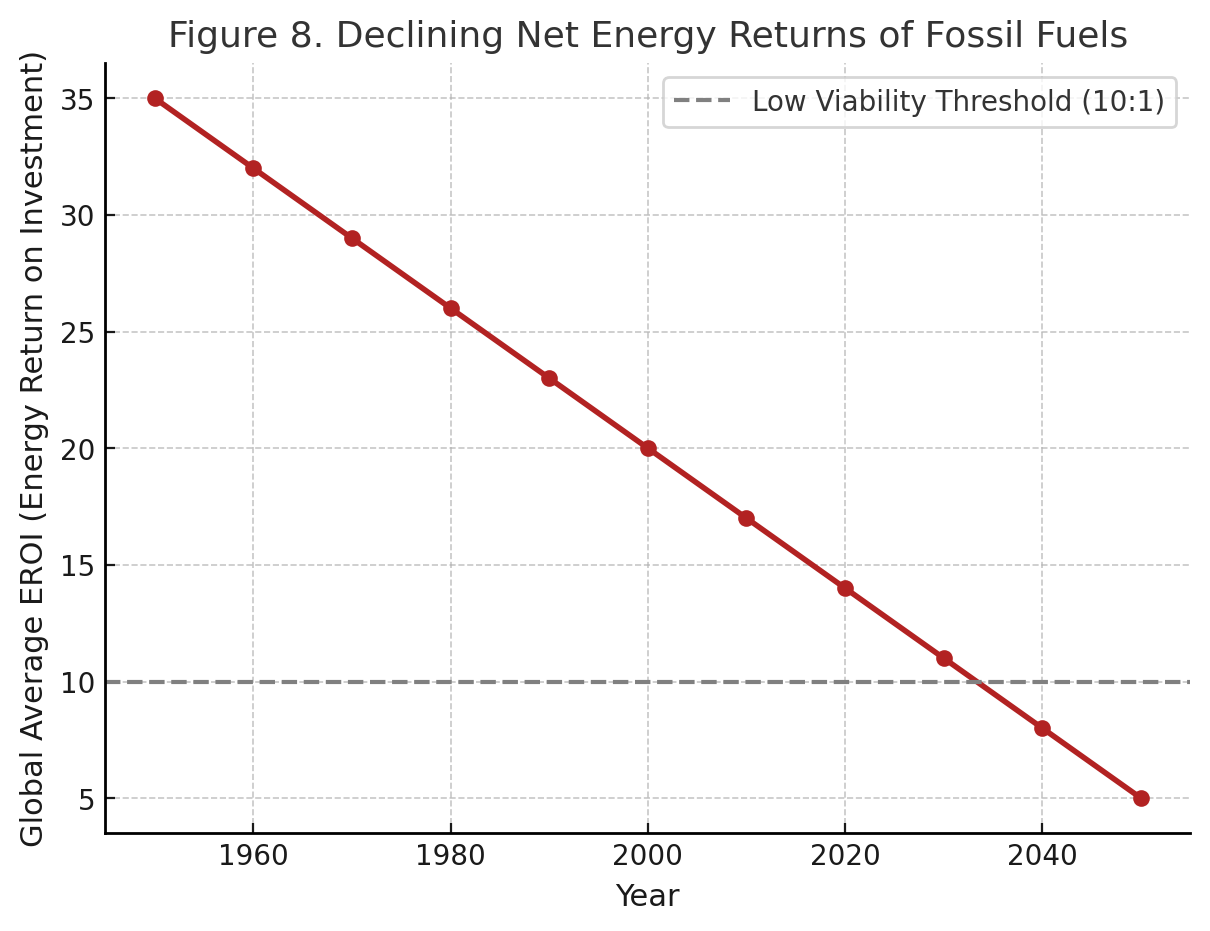

The hidden driver: declining net energy

The key measure here is Energy Return on Investment (EROI): how much energy we get back for every unit of energy we invest in extracting it. In the mid-20th century, oil fields delivered returns as high as 35:1. Today, the global average for oil and gas has fallen below 15:1, with unconventional sources like tar sands and shale oil as low as 2:1 (Ahmed 2017, pp.15–22). In practical terms, this means we must burn more energy and spend more capital just to keep producing the same amount.

The global EROI of fossil fuels peaked around the 1960s and has been falling ever since.

By 2050, the oil industry may be consuming half the energy it produces just to keep pumping — a practical, economic and geophysical impossibility that would require, in effect, massive subsidisation from civilisation (entailing its effective collapse) to take place (Ahmed 2024, p.12).

This is a key driver of why global growth has slowed since the 1970s. As net energy has declined, so too has GDP growth, while debt and financialisation have soared to fill the gap (Ahmed 2024, p.13). What looks to Clark like the collapse of modernity is, at root, the decline of the very energy metabolism that made modernity possible.

Want deeper insights? Get access to detailed macrointelligence, scientific white papers, and investor briefings by subscribing to premium...

Critical slowing down: economies near tipping points

Economists puzzle over why recessions since the 1970s have grown longer, deeper, and harder to recover from. In systems science, this is called critical slowing down — the signature of a system nearing a tipping point. Professor Tim Jackson of the University of Surrey has shown that recessions in the UK economy have stretched out over the past century, mirroring the long-term decline in net energy (Ahmed 2024, p.13).

This isn’t coincidence. Energy is the master resource. As its surplus contracts, economies lose resilience. The repeated shocks Clark lists — financial crises, debt spirals, inflationary spikes — are not random. They are signals that industrial civilisation is approaching a systemic threshold.

The feedback amplifier: Earth and Human systems entwined

Finally, Clark frames geopolitics — Putin’s aggression, Trump’s authoritarian drift, China’s rise — as though they are driven purely by human ambition and rivalry. But in reality, they are symptoms of a feedback process linking the Earth system and the human system.

I call this the ESD–HSD feedback loop: Earth System Disruption drives Human System Destabilisation, which in turn feeds back into more Earth disruption. Climate-induced drought in Syria, for instance, converged with declining oil revenues and food price spikes to help trigger civil war (Ahmed 2017, pp.49–53). The Arab Spring uprisings more broadly were fuelled by converging food, water, and energy crises (Ahmed 2017, p.57). These are not isolated stories. They are case studies of a systemic pattern: as energy and ecological buffers erode, societies fracture, polarise, and sometimes collapse.

Shocks to the Earth system trigger polarisation in the human system. Societies then double down on securitisation and repression, which may suppress symptoms in the short term but leaves the root drivers untouched — ensuring that shocks intensify and destabilisation deepens.

Not the end of modernity — the release of industrial civilisation

So when Clark calls this the “end of modernity,” he is both right and wrong. Right, because something is ending. Wrong, because it is not just a cultural epoch, but the energy-civilisational regime that powered it. What we are living through is the release phase of industrial civilisation’s adaptive cycle (Ahmed 2024, p.4). Its institutions are brittle because its energy metabolism is failing. Its narratives are hollow because its material foundations are eroding.

This isn’t fatalism. In the adaptive cycle, release opens the possibility of reorganisation. But to see that, we must first understand that the storm breaking over us is not just ideological. It is systemic.

The Planetary Phase Shift: What the Data Shows About Metamorphosis

Up to this point, I’ve shown how the turbulence Clark describes — multipolar disorder, the collapse of shared meaning, climate looming like a storm cloud — are symptoms of a civilisation entering the release phase of its life-cycle. But the release phase is never only about breakdown. In Holling’s adaptive cycle, release creates space for reorganisation. The collapse of one system sets the conditions for something new to emerge. And in our present moment, you can already see the outlines of that metamorphosis in the transformation of the very production systems that sustain human civilisation.

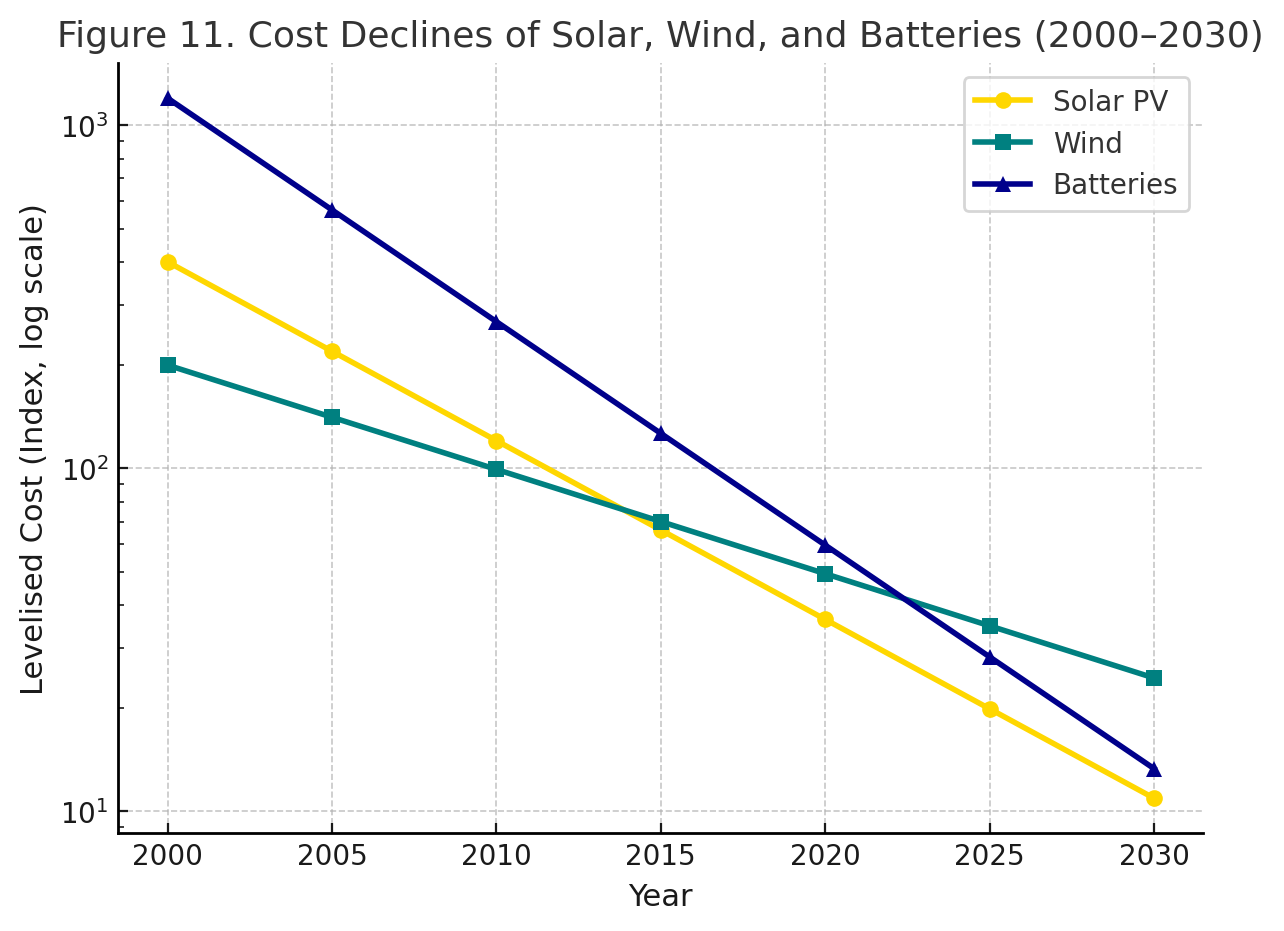

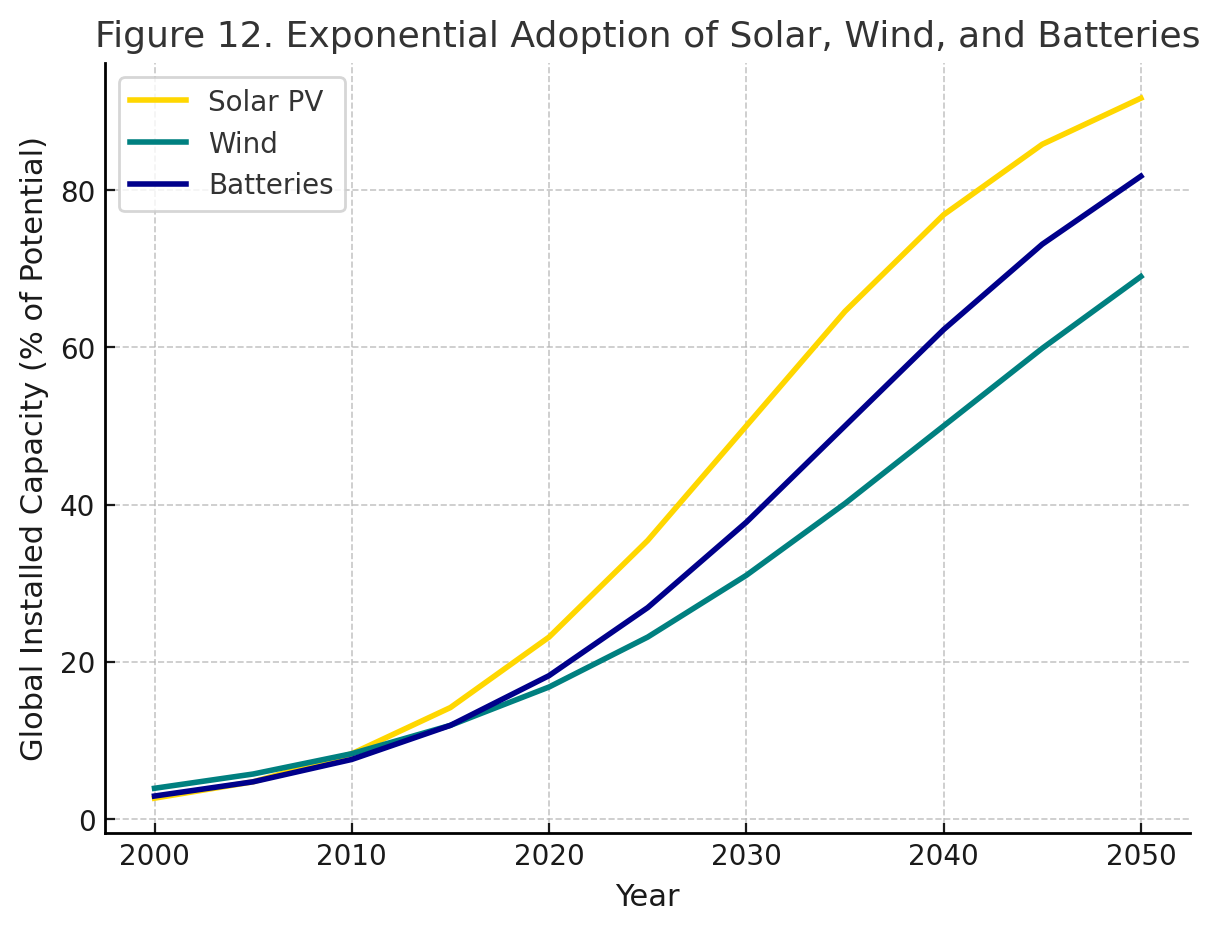

Think first about energy. For two centuries, industrial civilisation was powered by fossil fuels. That era is drawing to a close. On one side, we have the terminal decline of fossil fuel net energy: the falling energy returns of oil, gas, and coal that I described earlier (Ahmed 2024, p.12). But on the other side, a very different pattern is taking shape. Over the last two decades, the costs of solar, wind, and battery technologies have fallen exponentially, while their adoption has accelerated.

The graphs are unmistakable: steep downward cost curves paired with steep upward adoption curves. Project them forward, and the evidence suggests that by mid-century solar energy will dominate global electricity production on economics alone. This is not speculation. It is the empirical signature of a disruptive phase transition.

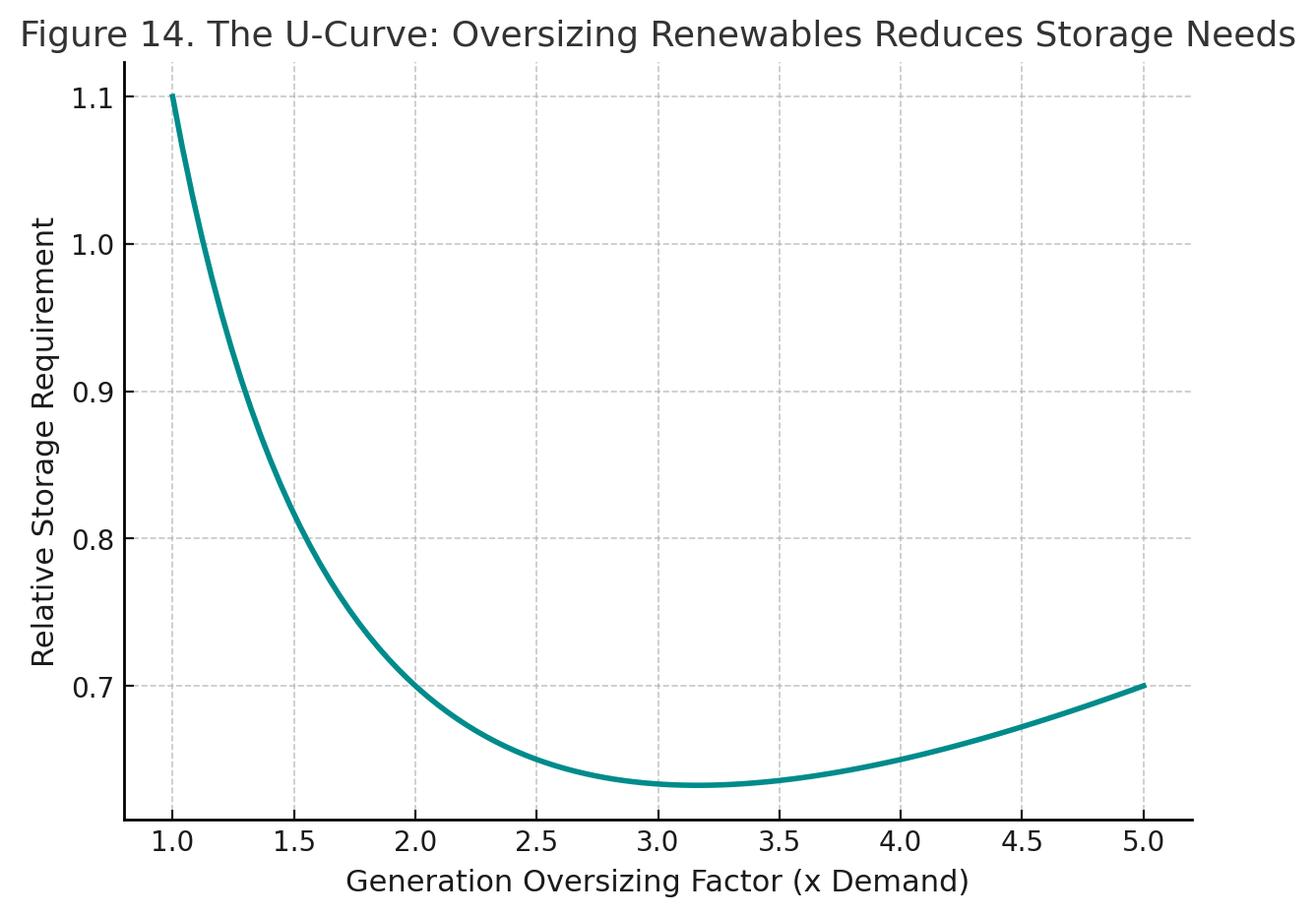

One objection always raised is storage: “the sun doesn’t always shine, the wind doesn’t always blow.” But here the data delivers a surprise. Analysis shows that by supersizing solar and wind capacity relative to demand, you can actually slash the amount of storage required — a counterintuitive “U-curve” relationship (Ahmed 2024, p.16).

Rather than making the system more expensive, this design principle makes it cheaper, more reliable, and less resource-intensive. In other words, if we design it well, the clean energy system ahead is not one of scarcity, but of superabundance: surplus near-zero marginal cost electricity for much of the year, with a materials footprint potentially hundreds of times lighter than the fossil system it replaces.

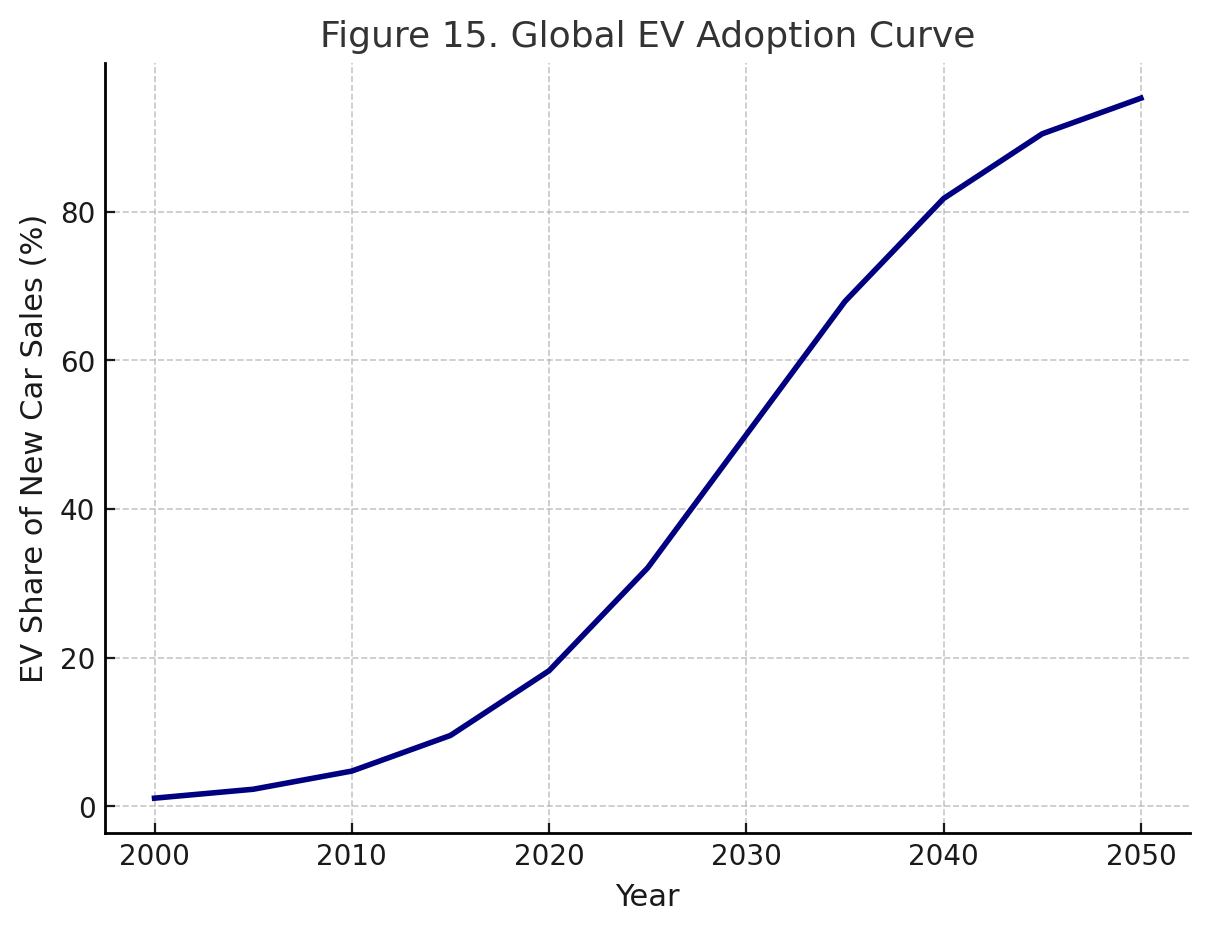

Now turn to transport, a sector that has always been tightly bound to energy. Here, too, the signs of transition are clear. Electric vehicles (EVs) are scaling globally on an unmistakable S-curve (Ahmed 2024, p.17). At the same time, autonomous driving technology is following a learning curve that, if maintained, will reach maturity by the mid-2030s (Ahmed 2024, p.18).

Combine these two trends and you don’t just get cleaner cars. You get the possibility of a fundamental shift in the mobility model itself: Transport-as-a-Service. Instead of private ownership, fleets of autonomous EVs could provide mobility that is cheaper, cleaner, and more efficient, while reducing materials demand and integrating seamlessly with oversized renewable grids. Of course, if EVs are simply bolted onto today’s car-ownership paradigm, they could worsen congestion and resource pressures. The point is that the possibility space is already open.

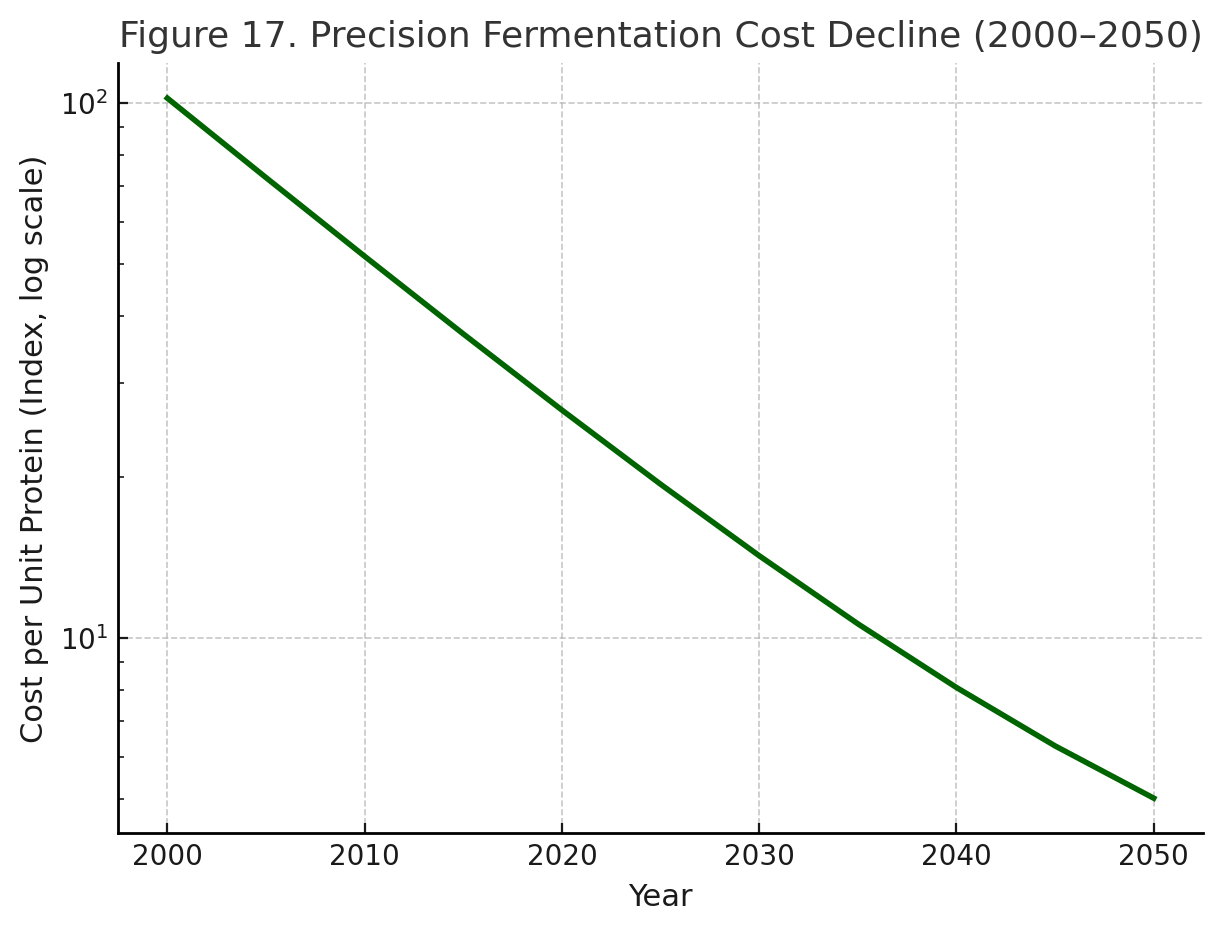

The same dynamic is unfolding in food systems. Industrial livestock farming is one of the largest drivers of land-use change, emissions, and biodiversity collapse. But it is also on the cusp of disruption. Precision fermentation and cellular agriculture — technologies that brew proteins the way we brew beer — have seen costs fall exponentially, with adoption projected to accelerate through the 2030s (Ahmed 2024, p.18–19).

If powered by renewables, these methods can be an order of magnitude more efficient than conventional farming, freeing up to billions of hectares of land for regenerative agriculture, rewilding, and carbon sequestration. Here again, the risk is path dependence: if these new protein systems scale on fossil fuel energy, they could entrench the very problems they are meant to solve. But the alternative is unprecedented: a food system that feeds humanity more efficiently harnessing both technological and natural means, while healing rather than devouring the planet.

Want deeper insights? Get access to detailed macrointelligence, scientific white papers, and investor briefings by subscribing to premium...

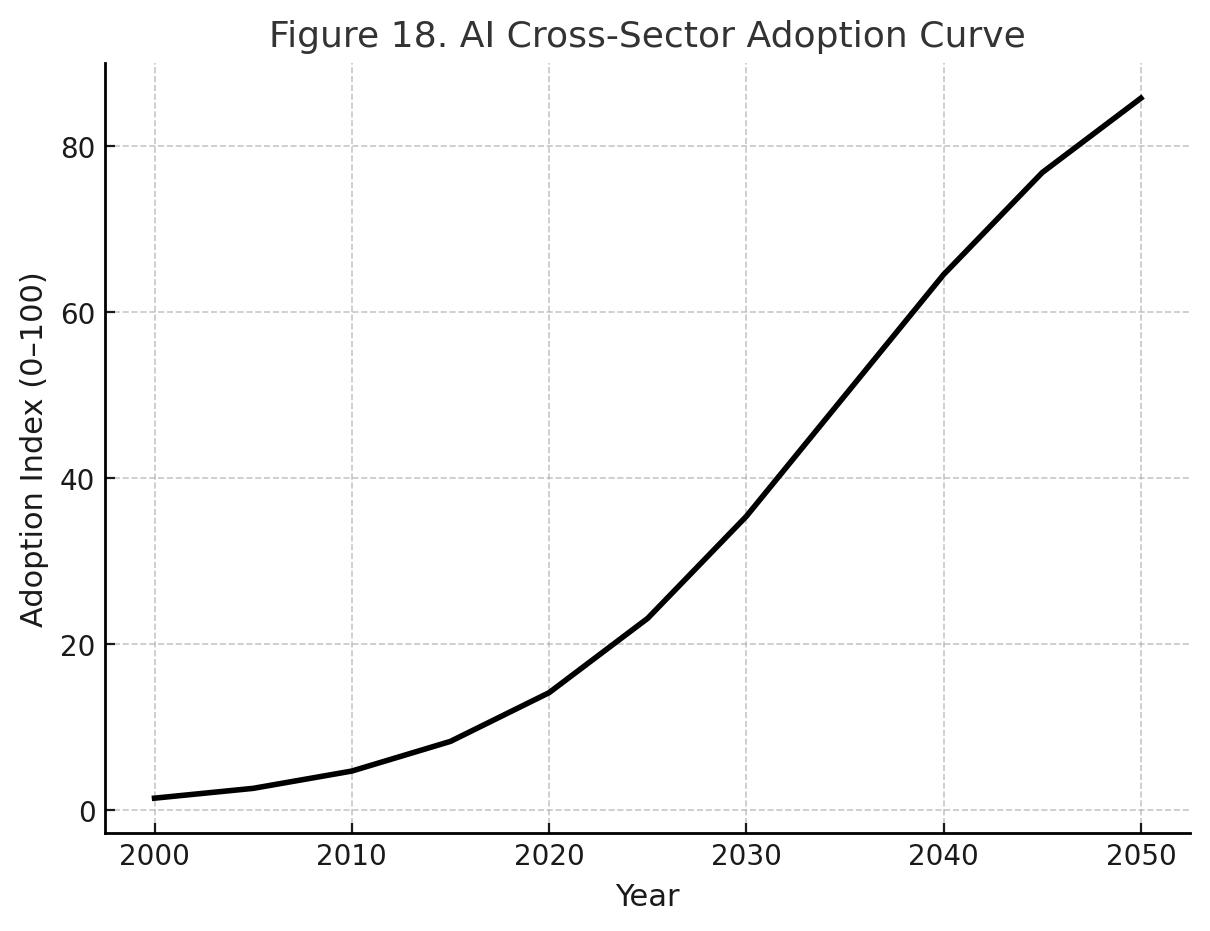

Finally, consider information, the realm where Clark’s instincts about media fragmentation were sharpest. Here too, a phase shift is visible. Artificial intelligence is diffusing rapidly across every sector, its costs falling, its performance rising, its adoption accelerating (Ahmed 2024, p.19).

At its best, AI can act as a coordination accelerator — balancing grids powered by variable renewables, optimising transport flows, enhancing the efficiency of food production. At its worst, inside today’s industrial-era organising systems, AI becomes a tool of surveillance, monopolisation, and disinformation. Whether it tips one way or the other will depend not on the technology itself, but on how we organise it.

What ties all these transformations together is a profound asymmetry. The hardware of civilisation — the material systems of energy, transport, food, and information — is changing faster than its software — the organising systems of politics, economics, culture, and governance. This is precisely what we expect in the back loop of the adaptive cycle (Ahmed 2024, p.20–22). The production system is evolving toward a new paradigm, but the organising system designed for the fossil fuel age cannot manage it. That is why our politics feels chaotic, our economies fragile, our cultures polarised. The mismatch between the hardware and software of civilisation is the defining tension of this planetary phase shift.

And this is also where the opportunity lies. The release of the old opens the space for reorganisation. The question is not whether energy, transport, food, and information will be transformed — that is already happening. The question is whether we will redesign the organising systems that govern them in ways that distribute their benefits, respect planetary boundaries, and enable a regenerative civilisation. That choice will determine whether the planetary phase shift leads to renewal or collapse.

Reframing Security and Geopolitics for the Back Loop

For Clark, the heart of the crisis is geopolitical. He sees a new world of multipolar rivalry, shaped by Russia’s war on Ukraine, China’s assertiveness, and Donald Trump’s America retreating from alliances. He reads Trump and Putin as corrosive forces intent on dismantling the order built after 1945. And in a narrow sense, he is right. But to stop there is to misread symptom as cause. These geopolitical convulsions are not the drivers of collapse. They are the ways industrial-era states are maladaptively responding to the release phase of civilisation’s life-cycle.

Here’s what that means. In the planetary phase shift, environmental and energy shocks drive what I call Earth System Disruption (ESD). Droughts, heatwaves, wildfires, food price spikes, floods, and storms all hit societies at once, eroding their economic base and straining state capacity. These shocks then reverberate through the human system as Human System Destabilisation (HSD): polarisation, institutional breakdown, protest, insurgency, and violence (Ahmed 2017, p.37; Ahmed 2024, p.9).

The problem is that most states interpret these crises through the lens of conventional security. Instead of addressing the underlying Earth system shocks, they double down on coercion, militarisation, and repression. The effect is to intensify HSD while leaving ESD untouched. This is the collapse feedback loop in action (Ahmed 2024, p.9). The more states securitise, the more brittle they become.

We have already seen this pattern play out. The Syrian civil war was not caused by climate change alone, but climate-linked droughts, collapsing oil revenues, and global food price spikes created the conditions for state failure (Ahmed 2017, pp.49–53). The Arab Spring more broadly was fuelled by the convergence of energy, food, and climate crises that governments could no longer buffer (Ahmed 2017, p.57). The same dynamics helped drive the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria, regime instability in Egypt, and escalating migration from the Sahel (Ahmed 2017, pp.61–68). In each case, authoritarian clampdowns and militarised interventions did not solve the problem; they amplified it.

Seen through this lens, the post-2022 intensification of Russia’s hybrid warfare in Europe, or Trump’s assault on U.S. alliances, look less like discrete events and more like systemic symptoms of states trapped in maladaptive responses. Russia’s war is not only a project of imperial ambition. It is also a response to the fragility of a petro-state facing declining net energy returns, climate disruption at home, and the erosion of legitimacy through stagnation. Trump’s retreat from multilateralism is not just a matter of ideology. It reflects the exhaustion of U.S. hegemony in an age when its own domestic economy has been hollowed out by energy decline and inequality.

This is why the true security frontier of the 21st century is infrastructural and planetary. The vulnerabilities that matter most are not whether NATO troops are stationed in Poland or Canada feels slighted by Washington. They are whether grids can withstand climate extremes, whether food systems can buffer price shocks, whether cities can cope with water scarcity, and whether energy transitions are designed for resilience rather than fragility. In short: the battlefield of the back loop is not the line of control between rival armies. It is the material foundations of life.

Clark closes his essay by warning that neutrality is not an option: Europe, he insists, must choose between democracy and authoritarianism. Again, he is right, but only half right. The deeper choice is whether to cling to the old organising system of militarised fossil modernity — a system already collapsing under its own contradictions — or to reorganise around infrastructures of regeneration. In the back loop, that choice is existential. Neutrality is indeed impossible. But the line that matters is not East versus West. It is collapse versus renewal.

Scenarios for the Back Loop

The back loop of the adaptive cycle is not an ending but a fork. Release clears space for reorganisation. But what emerges is not preordained. To make this clear, let me sketch two pathways — one where breakdown cascades into collapse, another where release opens into renewal.

Scenario One: The Spiral of Collapse

By the 2030s, industrial states cling ever harder to the fossil fuel paradigm even as its net energy erodes. To prop up flagging output, governments turn further to energy-hungry shale, tar sands, and deepwater drilling into new territories and former nature reserves. As the oil industry consumes more and more of the energy it produces just to keep pumping, economies are forced to spend more to subsidise them. These are concealed in evermore elaborate policy structures, but the net result is a collapse in public spending and the degradation of modern infrastructure (Ahmed 2024, p.12).

AI, hailed as the solution, is pressed into service — but under fossil fuel conditions. Models are trained and cooled in vast server farms drawing on coal and natural gas, competing with agriculture for freshwater, worsening both emissions and scarcity. Rather than accelerating transition, AI becomes an amplifier of collapse: optimising depletion, accelerating extraction, and perfecting disinformation systems that fracture public meaning.

At the same time, precision fermentation is rolled out without a renewable base. Instead of freeing land and cutting emissions, it locks food production into carbon-intensive grids and deepens dependence on fragile supply chains. Water stress intensifies: megadroughts empty reservoirs while aquifers collapse under relentless pumping. Crop failures trigger food price spikes that cascade into unrest.

Societies polarise. Authoritarian leaders promise security but deliver repression. Trust in science and institutions collapses, replaced by echo chambers and conspiracy. Clark’s intuition of “the end of modernity” materialises here as lived despair: the grand narrative dissolves not only in politics, but in daily life, where people experience dislocation, meaninglessness, and chronic insecurity.

What emerges is not apocalypse in one blow, but a grinding polycrisis spiral: AI reinforcing authoritarianism, fossil fuels devouring themselves, water and food systems collapsing in tandem, and societies losing the capacity to make sense of what is happening. By the 2040s, industrial civilisation might still exist, but in a diminished, brittle form — patchworks of fortified enclaves and degraded ecosystems haunted by the memory of abundance.

Scenario Two: Regenerative Reorganisation

Now imagine another path. In this future, the starting point is not technology but commitment: an intentional civilisational decision to renew our relationship with the Earth. The recognition spreads that prosperity cannot be sustained by extracting and degrading, but by aligning human systems with planetary boundaries. Out of this ethos, new institutions and values emerge — stewardship, reciprocity, participation.

This cultural shift unlocks the potential of the very disruptions now underway. Solar and wind are not just deployed, they are supersized and coupled with storage, grids, and governance that treat clean electricity as a common good (Ahmed 2024, p.16). That surplus powers precision fermentation and cellular agriculture, making proteins at a fraction of today’s energy and water use, and in turn freeing land for regeneration (Ahmed 2024, p.19).

AI is designed for abundance only within limits: powered by firm renewable power, cooled through closed-loop water systems, and governed transparently to prevent monopoly and ensure public stakeholder ownership given AI has been trained on collective human intelligence. Rather than fuelling disinformation, this allows AI to be harnessed to balance grids, manage distributed transport fleets, optimise circular economies and enhance distributed knowledge.

In mining and materials, new governance models emerge. Communities participate in decision-making; circular economy protocols ensure that extraction is minimised and ecological restoration is prioritised. Ownership diversifies: energy cooperatives, public trusts, and commons-based systems distribute the benefits of abundance rather than concentrating them.

Crucially, these transformations do not unfold in isolation. They generate positive feedback loops: solar abundance makes PF/CA cheap and clean; PF/CA land release allows ecosystems to recover, stabilising climate; AI orchestrates energy and transport, increasing efficiency; regenerative governance builds resilience and public trust, which in turn accelerates adoption.

By the 2040s, the outlines of a new life-cycle are visible. This is not techno-utopia. It is turbulent, contested, and uneven. But it is also a civilisation re-anchored: producing more than enough energy, food, and mobility within planetary limits, while restoring ecosystems and deepening democracy. The story that emerges is not the end of modernity, but the birth of a planetary civilisation committed to renewal.

Want deeper insights? Get access to detailed macrointelligence, scientific white papers, and investor briefings by subscribing to premium...

Conclusion: The Real Fork in the Road

Christopher Clark is right to sense that something immense is ending. The world we once called “modernity” — powered by cheap fossil energy, stabilised by Cold War bipolarity, glued together by mass media and national parties — is disintegrating before our eyes. But he misreads this as the end of an idea. What we are really living through is the end of a civilisational life-cycle.

Seen through the lens of the planetary phase shift, today’s turbulence is not random: it is the release phase of industrial civilisation. Declining net energy, breached planetary boundaries, and compounding feedback loops between Earth system disruption and human system destabilisation have eroded our institutions. The collapse of trust, the rise of authoritarian populism, the fragmenting media sphere — these are the surface symptoms of a system whose material metabolism can no longer sustain its old form (Ahmed 2024, pp. 9–13).

But release is not the end. It is the opening into reorganisation. Already, we can see new patterns forming: clean energy systems capable of superabundance, food systems that could regenerate land rather than devour it, information systems that can accelerate coordination rather than confusion. The question is whether we will design the organising systems — the politics, ownership models, and cultural commitments — that allow these production transitions to reinforce each other in ways that sustain life within planetary boundaries (Ahmed 2024, pp. 20–22).

That is the real fork in the road. We can cling to the industrial organising system and spiral into collapse: AI in the service of fossil fuel extraction and depletion, water and food crises feeding authoritarianism, meaning itself dissolving in disinformation. Or we can embrace a planetary ethos of stewardship, reciprocity, and regeneration, unleashing amplifying feedback loops of abundance within limits.

So yes, neutrality is not an option. But the line that matters is not between East and West, liberalism and authoritarianism, modernity and post-modernity. The real choice is between collapse and renewal. Between clinging to a dying system, or co-creating the birth of a new civilisational life-cycle. Between an ending that consumes us, and an ending that makes space for a beginning.

If you appreciated this piece, sign up to get this newsletter delivered straight to your inbox for free. Or join premium to get access to deeper insights, white papers, scientific research and macrointelligence reports