A report commissioned on behalf of a cross-party group of British MPs authored by a former UK government advisor, the first of its kind, says that industrial civilisation is currently on track to experience “an eventual collapse of production and living standards” in the next few decades if business-as-usual continues.

The report published by the new All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Limits to Growth, which launched in the House of Commons on Tuesday evening, reviews the scientific merits of a controversial 1972 model by a team of MIT scientists, which forecasted a possible collapse of civilisation due to resource depletion.

The report launch at the House of Commons was addressed by Anders Wijkman, co-chair of the Club of Rome, which originally commissioned the MIT study.

At the time, the MIT team’s findings had been widely criticised in the media for being alarmist. To this day, it is often believed that the ‘limits to growth’ forecasts were dramatically wrong.

But the new report by the APPG on Limits to Growth, whose members consist of Conservative, Labour, Green and Scottish National Party members of parliament, reviews the scientific literature and finds that the original model remains surprisingly robust.

Authored by Professor Tim Jackson of the University of Surrey, who was Economics Commissioner on the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission, and former Carbon Brief policy analyst Robin Webster, the report concludes that:

“There is unsettling evidence that society is tracking the ‘standard run’ of the original study — which leads ultimately to collapse. Detailed and recent analyses suggest that production peaks for some key resources may only be decades away.”

The 1972 team used their system dynamics model of the consumption of key planetary resources to explore a range of different scenarios.

As Professor Jackson and Webster explain in the new APPG report:

“In the standard run scenario, natural resources (for example oil, iron and chromium) become harder and harder to obtain. The diversion of more and more capital to extracting them leaves less for investment in industry, leading to industrial decline starting in about 2015. Around 2030, the world population peaks and begins to decrease as the death rate is driven upwards by lack of food and health services.”

Not all the model’s scenarios result in this outcome, but the majority of them “show industrial output declining in the 2020s and population declining in the 2030s. The researchers didn’t put precise dates on their projections. In fact, they deliberately left the timeline somewhat vague.”

Resource decline

The new APPG report flags up two major challenges facing global society: the overconsumption of planetary resources and raw materials, and the breaching of critical ‘planetary boundaries’ triggering irreversible environmental changes.

According to recent peer-reviewed scientific studies reviewed by the APPG’s report, key resources like phosphorous (essential for fertilising soil in agriculture), coal, oil and gas have “either already reached peak production or will do so within the next 50 years.”

The report in particular assesses evidence regarding ‘peak oil’ — the point when oil production hits its maximum possible production, after which it begins to decline. One recent model, the report finds:

“… suggests that overall oil production is in fact peaking already. The combination of declining conventional oil with increasing unconventional oil supplies then results in a ‘plateau’ in supplies to the end of the century, before a decline begins.”

Global fossil fuel production, the model indicated, “is likely to peak in around 2025” — which is less than 10 years away:

“World fossil fuel production is likely to peak in around 2025… largely as a result of Chinese coal production peaking. In short, unconventional oil seems to buy us several more decades before resource depletion starts to bite.”

An important and often misunderstood issue clarified by the report is that the risk of collapse is not because resources are running out, but because the quality of the available resources is declining, while the cost of extracting this lower-quality resource is increasing.

Collapse happens not due to “the absolute exhaustion of resources but from a simple and inevitable decline in resource quality.”

Planetary boundaries

The overconsumption of planetary resources has increasingly led industrial civilisation to disrupt ecological processes regulating land, ocean and atmosphere, which underpin a ‘safe operating space’ for human survival.

Four of these ‘planetary boundaries’ — biodiversity loss, damage to phosphorous and nitrogen cycles, climate change and land use — have already been crossed.

“Humanity has changed the natural environment so profoundly that we may have created a new — and far more unpredictable — geological epoch, according to recent research. The relatively stable environment of the Holocene, an interglacial period that began about 10,000 years ago, has provided the conditions for human societies to develop and thrive. Now, however, the world has entered a new era known as the Anthropocene, where the activities of humans are the dominant influence on the atmosphere and environment.”

The world has just 6 years left to “completely decarbonise the economy” and thereby avoid a rise in global average temperatures of 1.5 degrees Celsius — beyond which we enter the realm of dangerous climate change.

Permanent recession

The combination of these converging crises shows that continued economic growth is reaching limits inherent to humanity’s relationship with the environment.

“The reasoning behind the claims of the Club of Rome is, in my view, clearly still valid,” said Dr. Rupert Read, a political philosopher at the University of East Anglia and chair of the Green House Think Tank. “And some of their scenarios model alarmingly closely what the world is like, now, 44 years on.”

According to APPG co-chair Barry Gardiner, Shadow Minister for Energy & Climate Change, speaking at the House of Commons launch event, he attended a recent IMF meeting where it was openly recognised that: “Austerity is not working, and instead more new investment is needed in low carbon technologies.”

According to the report authors, growth could well be coming to an end, permanently.

They point out that even Larry Summers, a former World Bank chief economist who served as Treasury Secretary under Clinton and Director of the White House National Economic Council under Obama, has argued that the world is in a new era of ‘secular stagnation’ — a condition in which developed economies show no prospect of ever returning to previous levels of economic growth.

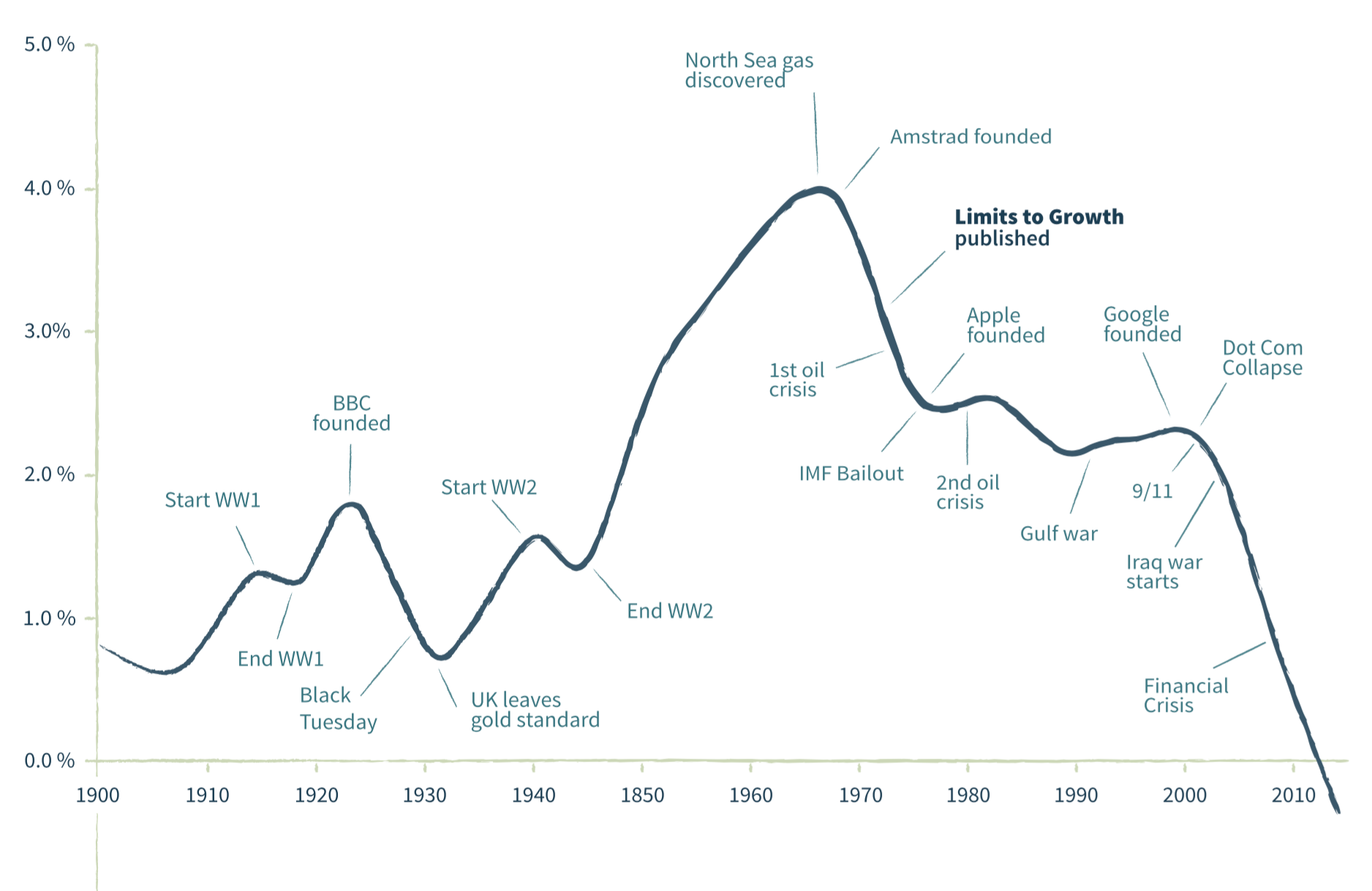

Productivity growth has slowed down dramatically in the US, and is even worse in the UK.

The APPG on Limits to Growth report cites Bank of England data revealing that UK productivity growth has been on a negative trajectory for over a decade — ever since the Dot Com collapse.

The APPG on Limits to Growth is chaired by Caroline Lucas (Green Party); and co-chaired by George Kerevan (SNP), Daniel Zeichner (Labour), Stuart Andrew (Conservative), Barry Gardiner (Labour) and Baron Howarth (Labour).

Its secretariat is the University of Surrey’s Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP), led by Professor Tim Jackson. Previously, Jackson had founded and run the university’s Sustainable Lifestyles Research Group, with joint funding from the UK Department for Environment and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), and the Scottish government.

From 2005 to 2010, lead APPG report author Jackson provided extensive advice on sustainability and economics to a range of UK government departments including DEFRA, the Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS), the Cabinet Office and the Home Office, as well as the UN Environment Programme and the European Commission.

Despite 40 years of mounting scientific evidence since the original ‘limits to growth’ study was released, he and his co-author lament, policymakers have largely failed to act.

“Many business leaders are now openly preparing for a world of resource constraints,” concludes the Jackson report. “But governments are still reticent to think beyond the short-term. The demands of Limits to Growth suggest an urgent need for policy-makers and politicians to take a longer term perspective: not just on urgent challenges such as climate change but also on resource horizons which are at best a few generations away.”

The current trajectory, the report recommends, should give new impetus to efforts to re-defining prosperity in a way that is more in tune with human nature, the natural environment, and their interrelationships:

“It is clear enough from this analysis that the economy cannot realistically countenance much more in the way of material growth… Visions for prosperity which provide the capabilities for everyone to flourish, while society as a whole remains within the safe operating space of the planet, are clearly at a premium here. A number of such visions already exist. Developing and operationalising them is vital.”

Among the mechanisms to do so, Club of Rome co-chair Anders Wijkman told the audience at the APPG’s launch, is shifting taxation from people to environmental “bads” and their causes. Another is to mobilise popular pressure on the financial sector itself: “One thing you can do tomorrow: ask your pension fund about their sustainable investment strategies.”

Ultimately, he said, the measure of GDP is deeply flawed, failing to capture the “full picture” regarding quality of life and human well-being — we need a “new measure” in which society is at the centre of how economic prosperity is defined.

APPG chair Caroline Lucas, Green Party MP of Brighton and Hove, said that this logic must be applied to the national budget: “We need to find a way to green the Treasury — because it has power over relevant ministers’ portfolios.”

But perhaps the most succinct advice summarising the new parliamentary group’s remit came through comments from the floor from Oxford University economist Kate Raworth:

“We need an economy in which we thrive whether we grow or not. Not the other way around.”