Donald Trump described the people behind the Manchester attack as “evil losers.”

And he’s right.

Terrorists like Salman Abedi, identified by police as the suicide bomber who detonated an explosive device to deliberately massacre children and young people, are quite literally evil losers.

A growing body of work shows that radicalised ‘jihadis’ who proudly go on to murder and rape other people en masse are more likely to be depressed and socially isolated than others from similar backgrounds.

A new report by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in The Hague has thrown light on this line of inquiry, confirming a very real correlation between violent extremist sympathies, depressive symptoms and a sense of social alienation.

The psychology of radicalisation

In the Netherlands, 60 percent of suspected jihadis had a history of mental health issues, ranging from “psycho-social problems to psychiatric disorders.” Of these, 25 percent suffered from “severe mental health problems” and were also “very active in the leadership of local jihadi networks and in the recruitment of new foreign fighters.”

Some experts point out that radicalised jihadis have ‘abnormal’ personality characteristics such as “low self-esteem, need for self-aggrandisement, abnormally high level of aggression, and dysfunctional conscience.” These can be reinforced by a prolonged social defeat experience — the “negative experience of being excluded from the majority group” — which in turn can lead to psychosis.

The experts did not suggest this would lead to a full-fledged psychotic disorder, implying lesser moral responsibility; but rather an episode or episodes of psychosis. These could result in persistent delusions associated with certain beliefs in the individual’s role as a savior of Muslims chosen by Allah.

In other words, despite the image of bravado and comraderi that ISIS likes to promote about its recruits on social media, the reality is the opposite.

“We did find a correlation between extremist sympathies and being young, in full-time education, relative social isolation, and having a tendency towards depressive symptoms,” wrote Kamaldeep Bhui, professor of cultural psychiatry and epidemiology at Queen Mary University of London, and author of an earlier study on the issue.

“Frequency of religious worship and attending a place of worship were not correlated with extremist leanings,” he added.

Someone like Salman Abedi, of course, was not just a depressed loser. Lots of people are depressed. Lots of people are lonely. They don’t go out and murder innocents, let alone children, who in the Islamic faith are considered masum, which means ‘pure and sinless’.

“I instruct you in ten matters: Do not kill women, children, the old, or the infirm; do not cut down fruit-bearing trees; do not destroy any town; do not cut the gums of sheep or camels except for the purpose of eating; do not burn date trees not submerge them; do not steal from booty and do not be cowardly.” (Abu Bakr, first Caliph after Prophet Muhammad, Malik ibn Anas, Muwatta, ‘Kitab al-Jihad’, hadith no. 958)

Propaganda

So what is it that pushes someone from this confluence of depression, alienation, and ‘social defeat’ into violence? In the case of ISIS, the research to date shows that most people who join up or sympathise are attracted to the group’s promise of meaning — a twisted, but seductive theology of heroic salvation.

People who join Islamist extremist groups, for the most part, are not grounded in religious observance. Instead, usually (though not exclusively) their first major encounter with Islam is through contact with an extremist preacher or recruiter outside the traditional mosque circuit, or by finding extremist literature — often online.

According to Charles Farr, former Director General of the Office for Security and Counter Terrorism (OSCT) in the Home Office (now chair of the Joint Intelligence Committee), “violent radicalisation in mosques or other religious institutions comprises no more than 1% or 2% of the total cases of radicalisation.” (House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, 2012)

Extremist propaganda has thus shifted from the public space to more private spaces, like homes, clubs, laptops and mobile phones.

For some, this can lead to a longer process which ISIS has invested considerably in fine-tuning. They convince their prey that the cause of their alienation and depression is outside of them, in the society in which they find themselves, ‘the West’. And they combine this with powerful audiovisual propaganda highlighting ‘the West’s’ evil destruction of Muslim life in Iraq, Syria and beyond.

A recent study in the Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice looked at a range of ISIS videos produced by their al-Hayat Media Centre.

The authors found that the videos specifically targeted “potential Western recruits and sympathisers by portraying life in the IS [Islamic State] as spiritually and existentially fulfilling, while simultaneously decrying the West as secular, immoral, and criminal. By utilising well-produced propaganda videos that tap into the dissatisfactions of Western Muslims, al-Hayat was shown to deliver a sophisticated and ‘legitimate’ message that may play a role in the larger radicalisation process.”

Theological illiteracy is actually a useful precondition for the prospective recruit, from ISIS’ perspective. It permits them to effectively promote these ideas in such a way that they push a person into accepting the ISIS worldview. Because the prospective recruit lacks the theological resources and grounding to see ISIS ideology for what it is — a flagrant bastardisation of Islam.

Combine this with the symptoms of depression and social isolation, and you have the basic features of the kind of person ISIS targets for its obscene cause.

Inner emptiness

This dynamic is not unique to ISIS, or to Islamist extremism.

Extremist movements offer their adherents a sense of belonging, meaning and purpose that they cannot find around them.

We see the same sort of dynamics with gang violence. Young people who join gangs are more likely to be depressed and suicidal — and these mental health problems only worsen after joining. Young men are especially vulnerable. Despite the greater risk of being assaulted or killed in a gang, young people who join gangs feel safer in doing so.

And so here is the bitter, horrifying irony of the Manchester attack by a radicalised 22-year old man who decided to massacre the most innocent and vulnerable people in our society.

Because, of course, it goes without saying that being depressed and lonely is no excuse. Sure, as social scientists we identify the correlations and begin to understand the complexity of the multiple causes that lead to violent radicalisation. None of that absolves a person from ultimately choosing who they really want to be.

But what we’re seeing is that the epidemic of mental health issues, rooted in an intensifying crisis of meaning across our societies, cannot be untangled from the myriad forms of dysfunction, chaos and violence that results: whether it’s gang violence, far right extremism or Islamist terror, we are seeing a pattern: for some, the inability to resolve one’s internal turmoil translates into choices that are devastating for the people around them — aggression, anger, crime, and ultimately violence, murder and terror.

“For the younger generation, the course of boredom, disappointment, disillusion and demoralisation is almost inevitable,” says psychologist John Schumaker. “As the products of invisible parents, commercialised education, cradle-to-grave marketing and a profoundly boring and insane cultural programme, they must also assimilate into consumer culture while knowing from the outset that its workings are destroying the planet and jeopardising their future.”

Islamist militants seek to ideologically exploit this impact of modernity, finds a paper in the Journal of Social and Political Psychology.

Modernity “makes one feel small, insignificant and isolated in the larger scheme of things”, a sense compounded by broken “household politics” and skewed “gender roles”.

The pull of new “theological teachings concerning death likewise feed this process”, and in doing so pushes the target into believing that the only way out is “a violent response, often involving self-sacrifice, to reassert the balance, which allows Islamists to take advantage of death-related anxieties and exaggerate the sense of confrontation with the world through apocalyptic prophecies.”

“The name, the label, covers the poverty of your inner being; you are petty, shallow, and through identification you hope to escape from your own emptiness. So the name, the country, the idea, become all-important, and for that you are willing to die and to kill.”

J. Krishnamurti, Madras, India, 1947

Whoever Salman Abedi was, on 22 May 2017, he made his choice to become a sick, pathetic, disgusting man. This choice was his own, whatever the factors that influenced it.

We may choose to understand the psychological mechanics of how he got there, how he became vulnerable to adopting ideas and values of hate — because if we don’t do that, then what really is the point of even discussing this?

But those mechanics can only throw some light on the acute nature of this sickness that is violent extremism — they cannot absolve or justify it.

Violent extremism is the sort of profound sickness where a person makes choice after choice following their isolation and depression to project their inner emptiness onto someone else.

To find someone, something, to blame.

It is a choice to stay sick, and become sicker.

Partners

And this is where Trump is wrong.

While his characterisation of Abedi and his ilk as evil losers could not be more apt in capturing the pathetic inner reality that defines them; the US president’s prognosis reveals the very same pathology he condemns.

“The terrorists and extremists and those who give them aid and comfort must be driven out from our society forever,” declared Trump. How?

“This wicked ideology must be obliterated — and I mean completely obliterated — and the innocent life must be protected. All civilised nations must join together to protect human life and the sacred right of our citizens to live in safety and in peace.”

Yet just days earlier Trump had signed his very own pact with the devil: a $110 billion arms deal with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Trump has no intention of obliterating the ideology of ISIS. Instead he is partnering quite deliberately with the country he accused of complicity in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. “Take a look at Saudi Arabia, open the documents,” he demanded not long ago.

And rightly so. US and British intelligence have long monitored Saudi Arabia’s sponsorship of Islamist militant groups, including al-Qaeda, for several decades.

Mark Curtis, the leading revisionist historian of British foreign policy and author of Secret Affairs: British collusion with radical Islam, lays out a detailed exploration of just a fraction of the evidence demonstrating specifically British collusion in Saudi Arabia’s support for Islamist terror.

“The ‘war on terror’ is a joke when your leading ally is the world’s biggest sponsor of terrorism,” he writes. “The backing of Saudi Arabia is part of a broader story: that British governments, both Labour and Conservative, have, in pursuing the so-called ‘national interest’ abroad, colluded for decades not only with the arch-sponsor of radical Islamism in Riyadh but sometimes with radical groups themselves, including terrorist organisations. They have connived with them, and often trained and financed them, in order to promote specific foreign policy objectives.”

This was the case in 2012 in Syria, where the Pentagon privately admitted that the West, Gulf states and Turkey were funneling support to al-Qaeda affiliated extremists at risk of declaring a ‘Salafist Principality’ to weaken Bashar al-Assad.

Since then, British intelligence estimates that about 850 Britons travelled to Syria and Iraq to join Islamist militant groups there, including ISIS. The BBC reports that about half of these had returned to Britain by February.

Why, you might wonder, are we allowing these people in without questions, without more stringent security protocols, despite the extraordinary powers we already have under Schedule 7 — applied, for instance, to the British director of the human rights group Cage to obtain his phone and laptop passwords?

Rat-line

The answer is deeply uncomfortable, but was inadvertently revealed in June 2015, when UK courts sought to try Swedish national Bherlin Gildo. He was charged with attending an extremist training camp in Syria, receiving weapons training and possessing information on extremists.

In pre-trial hearings, prosecuting lawyer for the Crown, Riel Karmy-Jones, told the court that from 2012 to 2013, Gildo had worked with al-Nusra Front, the “proscribed group considered to be al-Qaeda in Syria,” many of whose followers went on to join ISIS. (Al-Nusra has since attempted to rehabilitate its image by publicly disassociating from al-Qaeda — a move which, however, was strongly supported by al-Qaeda largely for PR purposes.)

The British trial collapsed when Gildo’s defence team pointed out he had joined an anti-Assad group — al-Nusra — which had received British government support. This support went through a CIA-MI6 al-Qaeda-facilitated arms “rat-line” from Libya to Syria.

The trial ended up inadvertently confirming what I’d been told a year earlier by Charles Shoebridge, a former British Army and Metropolitan Police counter terrorism intelligence officer: that the US and UK “through the covert work of MI6 and the CIA… played a key role in facilitating the flow of arms and jihadist fighters to Syria from such places as Libya, the Caucuses and Balkans, with the aim of militarily boosting those fighting Assad.”

At the same time, while this ‘rat-line’ was going on, British authorities “turned a blind eye to the travelling of its own jihadists to Syria, notwithstanding ample video etc. evidence of their crimes there,” said Shoebridge:

“Despite such overseas terrorism having been illegal in the UK since 2006, it’s notable that only towards the end of 2013 when ISIS turned against the West’s preferred rebels, and perhaps also when the tipping point between foreign policy usefulness and MI5 fears of domestic terrorist blowback was reached, did the UK authorities begin to take serious steps to tackle the flow of UK jihadists.”

Yet such steps appear to have been undermined by the British government’s embarrassment over its own security agencies facilitating military and financial support to these jihadist groups.

The British government has so far denied that Abedi was directly connected to a wider network — but he had at one point come to the attention of MI5 as an associate of Isis recruiter Raphael Hostey, killed in a drone strike in Syria in 2016.

Shortly before embarking upon his act of mass murder, he had arrived back from a weeks-long trip to Libya (and possibly Syria). It wasn’t his first.

Abedi reportedly grew up in a tight-knit ethnically Libyan community heavily opposed to Ghaddafi’s regime, which in itself would be no surprise. But back in Libya, the Telegraph claims:

“A group of Gaddafi dissidents, who were members of the outlawed Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), lived within close proximity to Abedi in Whalley Range… Among them was Abd al-Baset Azzouz, a father-of-four from Manchester, who left Britain to run a terrorist network in Libya overseen by Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s successor as leader of al-Qaeda. Azzouz, 48, an expert bomb-maker, was accused of running an al-Qaeda network in eastern Libya. The Telegraph reported in 2014 that Azzouz had 200 to 300 militants under his control and was an expert in bomb-making.”

In NATO’s Libya intervention to topple Ghaddafi, the US and British partnered with the very same al-Qaeda affiliated groups, including LIFG.

In March 2011, Nato-backed Libyan rebel leader Abdel-Hakim al-Hasidi openly admitted that al-Qaeda jihadists who had fought Western troops in Iraq were fighting on the frontlines to topple Ghaddafi. “Members of al-Qaeda are also good Muslims and are fighting the invader,” he said.

According to former CIA officer Bruce Reidel at the time:

“There is no question that al-Qaeda’s Libyan franchise, Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, is a part of the opposition. It has always been [Muammar] Gaddafi’s biggest enemy and its stronghold is Benghazi.”

Canadian intelligence files show that senior Nato leaders knew military action would likely lead to “a long-term tribal/civil war” in Libya, especially if “opposition forces receive military assistance from foreign militaries”.

The opposition, intelligence agencies confirmed, were strongly tied to al-Qaeda and other violent Islamist groups.

Even the State Department conceded in its 2012 Country Reports on Terrorism that in early 2011, in the wake of the collapse of Ghaddafi’s regime, “LIFG members created the LIFG successor group, the Libyan Islamic Movement for Change (LIMC), and became one of many rebel groups united under the umbrella of the opposition leadership known as the Transitional National Council. Former LIFG emir and LIMC leader Abdel Hakim Bil-Hajj was appointed the Libyan Transitional Council’s Tripoli military commander during the Libyan uprisings and has denied any link between his group and AQ.”

Sit with that for a second.

The head of the US-UK’s favoured post-war regime in Libya in 2011 was a former al-Qaeda leader who in 1997 wrote a glowing letter of support to the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

Abedi’s school associate claimed that he had travelled to Libya that very year in 2011, and had returned to the UK completely changed, religiously head-strong.

The Kingdom and ISIS

As the collapsed UK trial of Bherlin Gildo corroborated, the Libya ‘rat-line’ led straight to Syria. There were close ties and weapons transfers between the NATO-backed operation in Benghazi and al-Qaeda affiliated rebels in Syria.

Trump, who took a keen interest in the secret documents Wikileaks obtained from Hillary Clinton and her staff, is no doubt aware that one leaked memo dated 17 August 2014, drew on “western intelligence, US intelligence and sources in the region” to conclude:

“We need to use our diplomatic and more traditional intelligence assets to bring pressure on the governments of Qatar and Saudi Arabia, which are providing clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIS and other radical groups in the region.”

The connection between reckless Anglo-American policies from Libya to Syria, and the erosion of our national security, lies before us in broad daylight.

Far from exerting “pressure” on Saudi Arabia to cease its “clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIS”, the Trump administration is instead supplying more arms to the very country which US government officials privately acknowledged is the chief state-sponsor of Islamist terrorism.

“The truth is that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is neither a stable, nor reliable nation — let alone a trusted ally”, said a statement on Tuesday by Kristen Breitweiser, Monica Gabrielle, Mindy Kleinberg and Lorie Van Auken of September 11th Advocates, whose husbands died in the 9/11 attacks:

“Too much evidence exists proving that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia financially and logistically supports groups like ISIS that commit lethal terrorist attacks around the globe…

“We respectfully reiterate that far from contributing to Middle East peace, this $110 billion weapons deal [with Saudi Arabia] will only foment more hatred, increase further violence, and contribute immeasurably to loss of innocent life at the diabolical hands of terrorists. Why would America or any American want to play any role in that — let alone a financial one, by knowingly cutting a deal and signing up for it?”

Yet Trump was merely following Theresa May’s lead.

Back in May, the Prime Minister defended the British government’s ongoing alliance with the world’s chief terror sponsor:

“… it’s important to engage, to talk to people, to talk about our interests and to raise, yes, difficult issues when we feel it’s necessary to do so.”

Prime Minister, is sponsorship of ISIS a “difficult issue” that you’ve discussed with the Kingdom lately?

Saudi Arabia, May said, was “important for us in terms of security,” and “important for us in terms of defence and yes, in terms of trade… But as I said when I came to the Gulf at the end of last year, Gulf security is our security and Gulf prosperity is our prosperity.”

That’s why after Trump’s announcement, stocks in the leading private military contractors went sky high. A further six giant energy companies are pitched to profit handsomely from the new Trump-Saudi mega-deals.

In this context, is it not thoroughly disingenuous to hear Trump promise to obliterate the “wicked ideology” responsible for the Manchester attack?

To hear Theresa May say, in all seriousness, that “we can continue to resolve to thwart such attacks in future, to take on and defeat the ideology that often fuels this violence and if there turn out to be others responsible for this attack to seek them out and bring them to justice”?

Conveniently, May’s immediate proposal for doing that involves no soul-searching whatsoever about Britain’s longstanding alliance with ISIS’ chief sponsor.

Instead, it involves deploying 5,000 British soldiers on the streets. We are militarising our society at home to protect our geopolitical alliances abroad.

And rather than recognise the fact that these very alliances have incubated the proliferation and consolidation of groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS, thus undermining US and British national security, Trump and May are hell-bent on keeping the show on the road.

Ideas, propaganda, need the lubrication of money to maximise their reach. The machinery of ISIS’ ideological indoctrination is funded by some of our closest allies in the Muslim world.

And the grievances this ideology uses to draw people to its cause is fueled by the death and devastation wrought with US and British support from Iraq to Yemen — where US and British arms are being used to massacre men, women and children from the air literally everyday.

Responsibility

“At some point there has to be a more concerted effort by the Muslim community to root out these people whose brains have been completely warped into thinking that this is the way they should be behaving,” said Piers Morgan on Good Morning Britain.

And I agree with him.

Muslims can and should do more.

Not because Piers Morgan said so — but because it is an integral part of our faith that we should speak and act against injustice when we see it.

And if a minority in our communities are turning to or sympathising with the mass murder of children in the name of our faith, then we have to accept that our religious institutions can do more.

They have to do more.

We have to do more.

This is not about blame. It’s about fact. And we need to admit to ourselves that our mosques and madrasahs and religious institutions are not providing many of our young people with a sense of meaning, belonging and purpose which connects them with wider society.

Nor are they informing them of the nuance, complexity and depth of our faith. And it is precisely within those gaps that groups like ISIS find their prey.

As Haroon Moghul writes, the Muslim world cannot simply pass the buck:

“The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, said a time would come to pass when Muslims would abandon Islam in droves, and the worst of people would be the most outwardly religious, and you have to wonder. Are we there yet?

And how much worse can it get?

I am not interested in people who demonize all of Islam; the vast majority of the world’s Muslims reject this violence. Wholeheartedly. I am instead interested in why so many millions can accomplish so little.”

Terrorism, Or What Shall Be Done I had refrained from writing anything about the horrific terrorist attack in...

Posted by Haroon Moghul on Tuesday, May 23, 2017

So should we Muslims do more? Yes. And many are actively trying to.

Yesterday, 37 (now 45) Muslim organisations from across the country signed a joint statement expressing outrage and condemnation of the Manchester attack. That’s in addition to dozens of individual statements put out by various Muslim groups, mosques and institutions.

BREAKING: 37 Muslim groups from across country sign joint statement of outrage against #manchesterattack / call for solidarity https://t.co/o5mZbJHHNl

— Dr Nafeez Ahmed (@NafeezAhmed) May 23, 2017

Several Muslim groups have launched crowdfunds to raise money for the victims. Muslim taxi drivers worked for free throughout the night of the attack, ferrying survivors and concert-goers to and fro; other Muslim groups offered shelter and food to people who needed help.

For my part, I and a group of British, American and European Muslims got together last March to create Perennial, a completely independent grassroots theological initiative to create in-depth online trans-sectarian resources on Islam’s approach to key questions — whether it be jihad, women, Shari’ah law, domestic violence, or other issues.

We did this because we believe that the tools of both Islamic and modern scholarship, which empower a person to distinguish between destructive ideology and authentic theology, are not widely available.

And the reality is this: such Islamic narratives which delegitimise the political theology of terror are anathema to ISIS. Fundamentally, ISIS views Muslims like me and my colleagues at Perennial — Sunni, Shi’a, Sufi — as apostates.

But as much as I see where Piers Morgan is coming from, there is a narrow logic to his argument that stems from a familiar inner emptiness. It disingenuously passes the buck.

It leads to Katie Hopkins saying “We need a final solution.”

Even if Hopkins knows nothing of Nazism - which I doubt - her "final solution" can only mean ethnic cleansing pic.twitter.com/U7SDYh4e8q

— Nick Cohen (@NickCohen4) May 23, 2017

It leads Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson to call for mass internment.

We need a State of Emergency as France has. We need internment of thousands of terror suspects now to protect our children. #Manchester

— Allison Pearson (@allisonpearson) May 23, 2017

It sanitises indiscriminate violence against ‘Them’, a logic which parallels ISIS’ own self-rationale for its indiscriminate violence against ‘Us’.

It diverts attention away from the reality that the highest British institutions do business with regimes in the Muslim world that partner with extremists.

It side-steps the deeply uncomfortable reality that the domestic leftovers of Britain’s military adventures abroad are emboldened networks of extremist sympathisers, which British authorities are literally afraid of prosecuting for fear of embarrasing MI5 and MI6 over their wanton liaisons with Islamist militants for geopolitical aggrandisement.

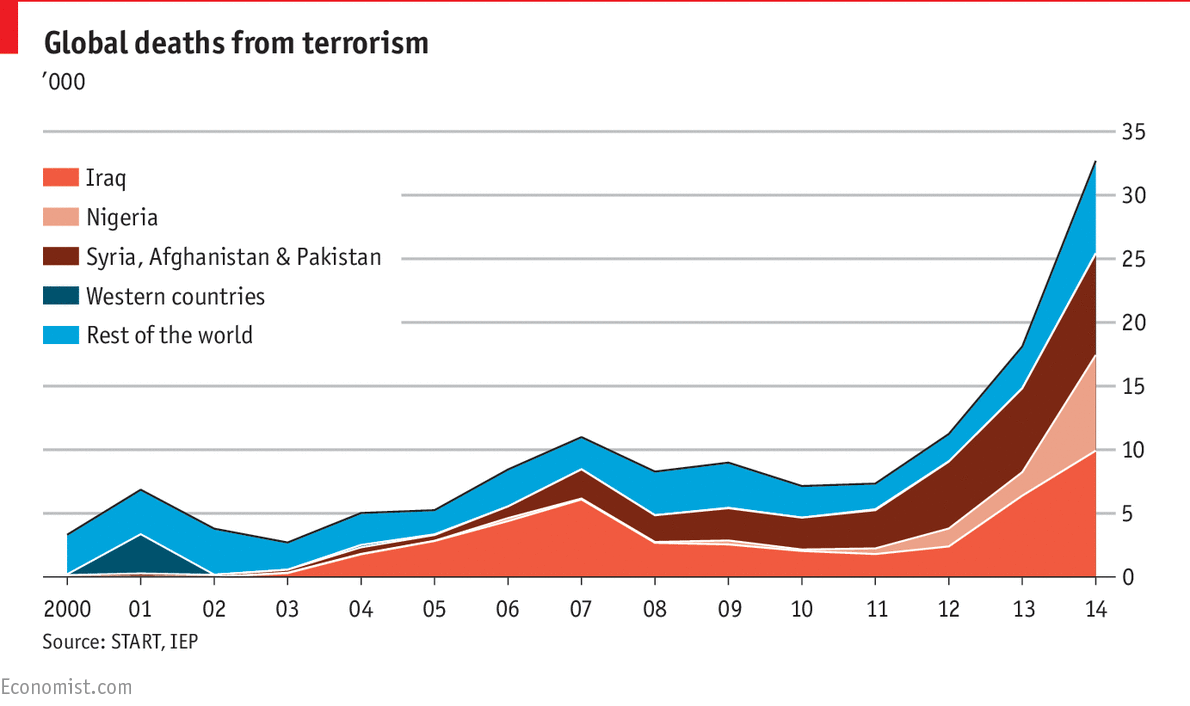

It is a convenient way of avoiding confrontation with the most inconvenient truth of all: that since 9/11, the staple tactics of the ‘War on Terror’ — military interventions, mass surveillance, drone assassinations, torture, rendition — have seen a massive acceleration in terrorist violence.

US State Department data shows that since 2001, terror attacks have skyrocketed by 6,500 percent, while the number of casualties from terror attacks has increased by 4,500 percent.

At what point are we going to wake up to the fact that the institutions of the ‘War on Terror’, too, have failed? Not just failed, but contributed to the violence we all fear?

At what point are we as a society going to stop pointing fingers at each other and accept co-responsibility for the failures of our institutions, secular and Muslim?

At what point will we recognise that terrorism is neither simply a ‘Western creation’ nor a ‘Muslim problem’ — but rather that the policies as well as the social, political, cultural and economic structures of both the Muslim and Western worlds have incubated a state of prolonged crisis from which the violence of extremist terror will continue to emerge without a drastic change of course?

At what point will we grow up and take responsibility?

I will close with a simple message: violent extremism of all kinds is a peculiar cancerous outgrowth of an inner emptiness. We cannot fill the void by hating the Other. We can only do it by embracing the Other.