In the name of ‘counting every casualty,’ the Pentagon is systematically undercounting deaths from the ‘war on terror’ and the ‘war on drugs,’ in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Latin America. Complicit in this great deception are some of the world’s most respected anti-war activists.

In this exclusive investigation, Insurge Intelligence reveals that a leading anti-war monitoring group, Iraq Body Count (IBC), is deeply embedded in the Western foreign policy establishment. IBC’s key advisers and researchers have received direct and indirect funding from US government propaganda agencies and Pentagon contractors. It is no surprise, then, that IBC-affiliated scholars promote narratives of conflict that serve violent US client-regimes and promote NATO counter-insurgency doctrines.

IBC has not only systematically underrepresented the Iraqi death toll, it has done so on the basis of demonstrably fraudulent attacks on standard scientific procedures. IBC affiliated scholars are actively applying sophisticated techniques of statistical manipulation to whitewash US complicity in violence in Afghanistan and Colombia.

Through dubious ideological alliances with US and British defense agencies, they are making misleading pseudoscience academically acceptable. Even leading medical journals are now proudly publishing their dubious statistical analyses that lend legitimacy to US militarism abroad.

This subordination of academic conflict research to the interests of the Pentagon sets a dangerous precedent: it permits the US government to control who counts the dead across conflicts involving US interests — all in the name of science and peace.

“Publishing in a peer reviewed journal is no guarantee that something is right… Peer review is an ongoing thing. It is not something that ends with publication. Everything in science is potentially up for grabs, and people are always free to question. Anyone might come up with valid criticisms… Science is a ruthless process. We have to seek the truth.”

— Professor Michael Spagat

1 — The Pentagon’s ‘peace’ network

In 2006, the leading British medical journal, The Lancet, published a comprehensive scientific study by a team of public health experts at John Hopkins University, which concluded that 655,000 Iraqis had died due to the 2003 Iraq War, mostly through violence. By extrapolation, the study implies that the total death toll to date now approximates 1.5 million Iraqis.

The Lancet estimate was rejected by the US and British governments, who favoured the lower estimates.

Researchers affiliated to Iraq Body Count (IBC), a leading British NGO tracking casualties through collation of open source reports, published several damning peer-reviewed scientific papers concluding that The Lancet’s 2006 findings were fundamentally flawed due to serious methodological errors, and even deliberate fraud.

Since then, The Lancet figure has been largely ignored as an erroneous outlier, with most scholars and journalists deferring to the IBC, whose database of casualty reports puts the civilian death toll since the 2003 invasion at 154,875 violent deaths. It is now widely assumed by journalists that IBC’s figures offer the most reliable insight into the scale of deaths in Iraq due to the war.

According to IBC, its figures “are not estimates” but rather constitute “a verifiable documentary record of deaths.”

But the debate over the death toll is not over. In March 2015, Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), a Nobel Peace Prize-winning doctors group, released a 97-page report concluding that approximately one million Iraqis had died since the dawn of the ‘war on terror’ due to its direct and indirect impacts.

So who is right?

IBC, Oxford Research Group, and the US government

The most widely-cited peer-reviewed critique of The Lancet’s 2006 Iraq death toll study, published in the Routledge journal Defense and Peace Economics, is authored by Prof. Michael Spagat, Head of Economics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Spagat’s startling conclusion was that “this survey cannot be considered a reliable or valid contribution towards knowledge about the extent of mortality in Iraq since 2003.” Many apparent anomalies identified by Spagat in the 2006 Lancet study are derived from his comparisons of Lancet data with the IBC dataset, which is put forward as a reliable litmus test of violent deaths.

When IBC was first founded by John Sloboda, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Keele University, and Hamit Dardagan, its work was done largely in partnership with the Oxford Research Group (ORG), where Sloboda was executive director from 2005 to 2009. Prof. Sloboda then became co-director, along with Dardagan, of ORG’s Every Casualty program.

In 2010, the same year that Spagat published his celebrated critique of The Lancet study, Spagat became a paid consultant to the ORG for its casualty recording program. From 2010 to 2012, he received a grant from ORG for over 10,000 pounds.

From 2012 to 2014, Spagat continued to collaborate with Sloboda and Dardagan under this program, which built on the data collection and analysis techniques established through IBC. The program claimed to aim for every single death through armed violence to be recorded.

The ORG Every Casualty program, however, is not an ideologically independent research project. The two-year initiative that ran from 2012 to 2014, ‘Documenting Existing Casualty Recording Practice Worldwide,’ was funded by a US government-backed agency which played a key role in the 2003 Iraq War.

USIP: neocon front agency

USIP was established by Congress in 1984, ostensibly as an independent, non-profit counterweight to the Pentagon that would function as a private, publicly-funded institution to promote peace. In reality, from inception USIP receives all its funding from the US Treasury, and has been closely tied to the executive branch, the US military intelligence community, and right-wing power.

According to a report by the Institute for Policy Studies’ (IPS) Right Web project, USIP’s board of directors has consistently been a veritable “who’s who of rightwing academia and government,” and its research suffers from a “conservative bias.”

USIP was established via an appendix to the 1985 Defense Authorization Act, which states that USIP’s Board of Directors would consist of fifteen voting members, namely the Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, the president of the Pentagon’s National Defense University in Washington DC, and twelve other Presidential appointees.

The legislation tasks the Institute to “respond to the request of a department or agency of the United States Government to investigate, examine, study, and report on any issue within the Institute’s competence, including the study of past negotiating histories and the use of classified materials.” Accordingly, the Act confirms that USIP “may obtain grants and contracts, including contracts for classified research for the Department of State, the Department of Defense, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the intelligence community, and receive gifts and contributions from government at all levels.”

USIP’s entire purpose is to function as a research arm of the executive branch and intelligence community, under the guise of being an independent private body.

As the legislation further clarifies: “The President may request the assignment of any Federal officer or employee to the Institute by an appropriate department, agency, or congressional official or Member of Congress”; and also: “The Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the Director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Director of Central Intelligence each may assign officers and employees of his respective department or agency, on a rotating basis to be determined by the Board.”

USIP has open access to classified intelligence community materials, and is directed by the legislation to utilize “to the maximum extent possible United States Government documents and classified materials from the Department of State, the Department of Defense, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the intelligence community.”

According to former University of California (Berkeley) sociologist Dr. Sara Diamond, an expert in US right wing politics, USIP was essentially set up to function as a “funding conduit and clearinghouse for research on problems inherent to US strategies of ‘low intensity conflict.”

“The USIP is an arm of the US intelligence apparatus,” wrote Diamond, and “intersects heavily with the intelligence establishment.” It is therefore little more than “a stomping ground for professional war-makers.”

USIP and Iraq

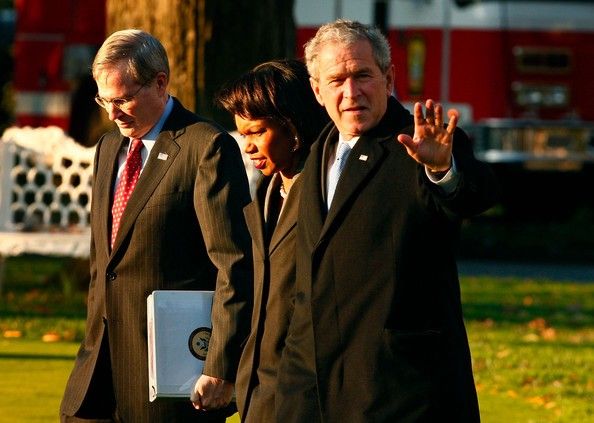

It is perhaps fitting, then, that the current chairman of USIP’s Board of Directors is Stephen Hadley, Bush Jnr’s National Security Adviser after Condoleeza Rice, and a former defense secretary for international security policy. After finishing his term at the Bush administration, he became a senior advisor for global affairs at USIP.

Hadley played a key role in the Iraq War. According to the Public Accountability Initiative, he “was the Bush White House official responsible for inserting faulty intelligence about Iraq’s nuclear capabilities (the ‘yellowcake forgery’) in Bush’s State of the Union in 2003.” He is also on the public affairs board of arms manufacturer, Raytheon.

In November 2003, President Bush signed the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act for Defense and for the Reconstruction of Iraq and Afghanistan, which came into force in 2004. Under the Act, Bush had authorized $10 million for USIP to conduct “activities supporting peace enforcement, peacekeeping and post-conflict peacebuilding” in Iraq.

By early 2004, USIP was directly involved in the occupation and efforts to legitimize and extend it on-the-ground. It had set-up its own office in Baghdad, where it began training pro-US “Iraqi facilitators and mediators” and providing 800 Iraqi government officials with a “decision-making training program.” USIP staffers also worked closely with US military Provincial Reconstruction Teams, US embassy staff, senior US military officers from coalition headquarters, and senior Iraqi government officials including aides to Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki.

In 2006, USIP convened and organized the bipartisan Iraq Study Group appointed by US Congress, which described “the use of force by the [US-backed] government of Iraq” as “appropriate and necessary to stop militias that act as death squads or use violence against institutions of the state.”

The Iraq Study Group report published in December 2006 argued that the bulk of violence was not the responsibility of the US, but of “a Sunni Arab insurgency, Shi’ite militias and death squads, al-Qaeda, and widespread criminality.” The US should therefore “support as much as possible central control by governmental authorities in Baghdad, particularly on the question of oil revenues.”

The report even advocated the delusion that “the presence of US troops is moderating the violence.”

In this context, the Group’s recommendations for monitoring violence in Iraq are worth noting. The report complained about “significant underreporting of violence in Iraq” because certain types of violence tend to be filtered out of US databases, such as a “sectarian attack” resulting in the “murder of an Iraqi,” or a roadside bomb that targets but “doesn’t hurt US personnel.” The presumption here is that the main source of violence being “underreported” was from sectarian and insurgent groups, rather than the US military and its client-regime.

The report thus recommended that the “Director of National Intelligence” and the “Secretary of Defense” support changes “in the collection of data about violence and the sources of violence in Iraq.” It called for the CIA to develop a joint “counterterrorism intelligence center” with the Iraqi government that would “facilitate intelligence-led police and military actions” — in other words, more US-Iraqi government violence against groups opposing US military occupation.

As investigative reporter Peter Byrne noted in 2007, USIP supported seven Iraq experts, the most prominent of which was Rend al-Rahim Francke, founder and director of the Iraq Foundation on Sunni/Shia Relations. Byrne reported that Francke, an Iraqi expatriate, had “along with the infamous Ahmed Chalabi abetted Bush-Cheney-Powell-Rice-Rumsfeld as they bullied and lied their way into invading Iraq in 2003. Francke later became the representative to the United States for the puppet government in Baghdad.”

Other USIP Iraq specialists, wrote Byrne, included many “former military officers” and others who had “learned the art of war inside the National Security Council, National Defense University and the Office of Secretary of Defense.” USIP had also “ heavily lobbied the Iraqi congress to pass the hydrocarbon law that privatizes Iraqi oil fields for Big Energy.”

USIP and IBC

USIP, with its pro-war sanitization and promotion of US violence in Iraq, is currently a funder of the very same executives, John Sloboda and Hamit Dardagan, who run the Iraq Body Count project.

The month after USIP’s Iraq Study Group released its report, Sloboda delivered a presentation via audio link at an off-the-record meeting hosted by USIP in Washington DC. His presentation criticized the use of survey samples to measure civilian casualties, and specifically targeted the related 2006 Lancet study. Many of the points Sloboda identified were later taken up by Michael Spagat.

The meeting was already biased against that Lancet study. While Les Roberts, a co-author of the Iraqi mortality survey, was present, he was outnumbered. Apart from Sloboda, the other panelists included Colin Kahl, then coordinator of the Obama Campaign’s Iraq Policy Expert Group, and a former Council of Foreign Relations fellow seconded to the Pentagon to work on counterinsurgency, counterterrorism and stability operations. From 2009 to 2011, Kahl was Obama’s deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East. He is currently, National Security Advisor to the Vice-President and deputy assistant to the President.

In a paper in International Security later in 2007, Kahl cited IBC data to argue that despite the regrettable loss of civilian life in Iraq, the US military has a far better track record of minimizing civilian deaths in Iraq than it did for previous wars.

In the acknowledgements to his 2010 critique of the Lancet study in Defence and Peace Economics, Spagat thanks Colin Kahl, indicating that a senior member of Obama’s Pentagon reviewed his manuscript before submission and publication.

The other panelist was Michael O’Hanlon, a signatory of a postwar statement on Iraq from the pro-Bush neoconservative Project for a New American Century (PNAC), an avid invasion supporter, and senior author of the Brookings Iraq Index. The latter, like IBC, relies on press reports for its estimates of the Iraq War death toll.

During his own presentation, Prof. Sloboda sycophantically told USIP that there has been “general identification of us as an ‘anti-war’ group. Well, we were — and remain — passionately opposed to THIS war… But where individual IBC members stand on other wars is a matter for them and them alone.”

Sloboda’s statement before USIP and its pro-war panel contradicts the IBC’s official rationale for what they call “our work: why we do what we do”: namely, “War’s very existence shames humanity.”

“Our own view is that the current death toll could be around twice the numbers recorded by IBC and the various official sources in Iraq. We do not think it could possibly be 10 times higher,” Sloboda added.

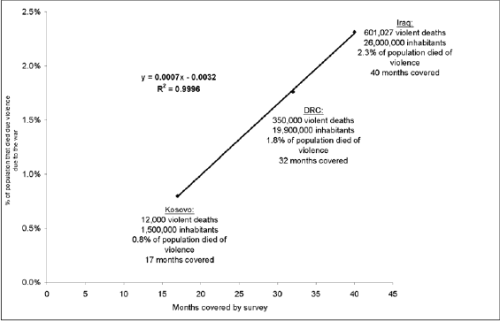

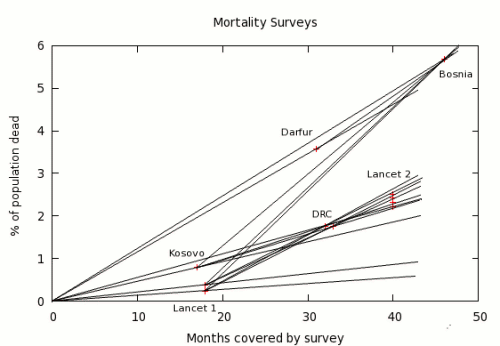

But as the 2011 Global Burden of Armed Violence report points out, it is widely recognized that “the limitations of incident reporting” in conflicts are “pronounced.” Various studies of “undercounting in specific conflicts reveal that the number of direct conflict deaths could, in extreme cases, be between two and four times the level actually captured by passive incident reporting systems.”

Depending on the nature of the conflict, the gap could be much higher than even 4. During the worst periods of violence in Guatemala’s civil war, for instance, only 10% of violent deaths were reported. The gap would be even higher when accounting for indirect deaths.

In Iraq, very few media outlets, Arab or Western, were able to travel outside the Green Zone, and were situated largely in Baghdad, although areas outside Baghdad were also subjected to massive violence. Even in Baghdad, most violent deaths were not reported by the media.

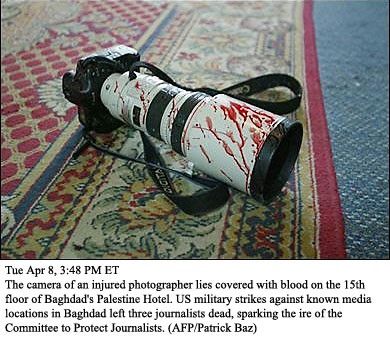

Dahr Jamail, one of the few unembedded journalists in Iraq who reported from outside the Green Zone, recounts an incident from eyewitnesses, including Iraqi police officers, where American troops opened fire on a civilian car driving home from work for no reason. When the police attempted to extract the body, they were also fired upon from US Humvees, despite their uniforms and police cars being plain to see.

“Events like this had become commonplace in occupied Iraq,” wrote Jamail in his seminal book, Beyond the Green Zone (2007). “Driving in Baghdad on any given day, funeral announcements on black banners hung everywhere from buildings, homes and fences. Yet these announcements of untimely Iraqi deaths never made it into the Western media, or even into most Arab media outlets.”

In other words, the degree to which IBC undercounts Iraqi violent deaths cannot be quantified so easily. Anyone with the slightest familiarity with the reality of the conflict of the ground would know this.

This was even acknowledged by a 2008 RAND analysis sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, which concluded that IBC’s dataset is “problematic,” because “its reliance on media reports may ‘favor’ particular types of attack, such as ones with higher fatalities, and regions where media outlets are concentrated, such as Baghdad. Therefore, undercounting is likely.”

Sloboda’s insistence that it is impossible for the death toll to be 10 times higher than the IBC count has no a priori nor statistical basis. Generic comparisons to other recent conflicts are misleading, as the 2003 Iraq War was ultimately an unprecedented invasion and occupation led by the world’s largest superpower.

Fronting for Western foreign ministries

Sloboda closed his USIP talk with a subtle plea for funding:

“With more substantial financial means, and the full co-operative involvement of nations and relevant international bodies, much more could be known, known to a higher degree of reliability, and known more quickly.”

And USIP funding is what Sloboda received. ORG’s Annual Report filed with the Charity Commission for the year ending 2010 confirms IBC as a “partner” of ORG’s USIP-funded ‘Recording the Casualties of Armed Conflict.’ The document mentions that IBC had by then calculated the Iraq War death toll at “over 122,000.”

In November 2012, the ORG casualty recording program led to the launch of a report at USIP in Washington DC. At the event Raed Jarrar, who had contributed to the IBC’s earliest 2004 casualty count based on a door-to-door survey, “highlighted the major discrepancies in the casualty figures from the Iraq war among the various recorders, including Lancet, Iraq Body Count, Opinion Research Business and the Associated Press.”

In June last year, IBC founding directors Sloboda and Dardagan set up and incorporated Every Casualty as a new, independent charitable company.

Both, including Michael Spagat, were appointed as directors of the company, which announced its launch in September. Spagat is also listed on the website as the organization’s ‘Casualty Recording and Estimation Advisor.’ As of October, Sloboda and Dardagan stepped down as company directors to take-on paid managerial posts at the new organization.

Every Casualty now lists its core funders as USIP, the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the German Federal Foreign Office, and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Despite Switzerland’s reputation for neutrality, all three European governments have supported US foreign policy in Iraq. Even Switzerland, in 2007, came under fire after revelations the government had sold arms destined for Iraq through Romania.

The IBC, of which Sloboda and Dardagan remain directors, is listed as a member of Every Casualty’s ‘International Practitioner Network,’ along with the Conflict Resource Analysis Center (CERAC), an organization founded and set-up by Michael Spagat in Bogota, Colombia. CERAC director Jorge Restrepo had also presented at the 2012 USIP-hosted Every Casualty event in Washington.

UPDATE (5th May 2015):

In a response to this report, Dr. Patrick Ball of the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG), states that my criticisms of USIP are “excessive and inaccurate,” and goes on to point out that HRDAG scientists I cite below along with other scientists “deeply critical of US policy” have received grants from USIP. Dr. Ball also criticizes what he calls my “speculation about how such funding might affect their substantive conclusions.”

Unfortunately, Ball’s criticisms here miss the mark. Due to USIP’s institutional and structural connections to the US government, foreign policy, and defense establishment, USIP will inevitably seek out types of project that fit its overarching ideological goals.

USIP’s deep-seated structural ideological biases are in fact widely understood in the peace research community, and have been demonstrated in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Prof. Sreeram Chaulia, for instance, in his study in the International Journal of Peace Studies published via the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University, finds that USIP “has been consistently used by US foreign policy elites as an instrument to counter the peace movement.” Research funded by USIP, Chaulia finds, functions:

“… by projecting the US as a benevolent hegemon that unswervingly pursues peace in various conflict zones… USIP is an ideational weapon that subjugates the knowledge of the American peace movement on behalf of the state… by validating certain ideological strands of peace research as ‘objective’ while disqualifying others as biased or ‘unscientific.’”

The goals of foreign policy departments are complex and do not preclude sponsorship of beneficial or critical projects, as long as they still fit the above ideological framework and goals. Ball’s dismissal of this critically important issue, as if who funds and frames research that purports to be ‘scientific’ is irrelevant to the integrity of the scientific process, is fundamentally problematic.

Secondly, it is due to this very question that natural and social scientists are expected as a matter of ethical obligation and academic integrity to disclose their funding sources for their research, and any other relevant affiliations which may pose a conflict of interest. In all of their research outputs, neither Spagat nor his colleagues at IBC ever chose to declare to the journals in which they published their funding sources and organisational affiliations to USIP, US military, and European foreign policy agencies. Dr. Ball offers no comment on this matter. Spagat’s and IBC’s data disclosures to Ball and his team are welcome but do not ameliorate this particular ethical breach.

Thirdly, Dr. Ball ignores the central revelation of this part of my investigation, which is that the historical and empirical record demonstrates unambiguously that USIP’s involvement in Iraq has from the outset been deeply politicized, and deeply influenced by the foreign policy agenda of the US government — to the extent of USIP having established an office in Baghdad through which senior USIP officers and representatives worked closely with the occupying power in Iraq. That USIP has funded positive scientific peace research in areas unrelated to Iraq has no bearing on the fact that USIP’s entire relationship to Iraq is deeply and directly embedded in official US government goals. Dr. Ball, for instance, ignores the very specific evidence I report above from the USIP-convened Iraq Study Group report on the question of casualty counting, demonstrating that USIP’s priorities undermined and whitewashed the task of assessing US forces’ role in violence. This is clear empirical evidence of USIP’s ideological bias on the issue of casualty counting and responsibility for violence in Iraq. Dr. Ball’s untenable and unscientific suggestion is that this bias should simply be ignored in assessing the integrity of USIP’s selection of an IBC-affiliate for funding. It should not.

[END]

Embedded anti-war activists

Michael Spagat, the loudest and most widely cited critic of the 2006 Lancet survey of Iraqi deaths due to the war, received his paid position as a consultant to the ORG’s casualty monitoring research program in 2010, the same year he released his main academic paper criticizing The Lancet’s survey.

That paper, ‘Ethical and data-integrity problems in the second Lancet survey of mortality in Iraq,’ was published in the Routledge journal Defence and Peace Economics in April 2010. The paper declared that he had no conflict of interest.

Three months later, Spagat received his two-year grant from ORG’s casualty recording program, run by Sloboda and Dardagan.

Spagat, however, had already been collaborating closely with IBC in preceding years, specifically in relation to fine-tuning NATO counter-insurgency practices.

In December 2008, Spagat published a paper in PLOS Medicine co-written with then IBC director, Dr. Madelyn Hsiao-Rei Hicks. Spagat and Hicks advocated that US and UK armed forces should use new casualty tracking tools, based on their own ‘Dirty War Index’ (DWI). The DWI, they wrote, “systematically identifies rates of particularly undesirable or prohibited, i.e., ‘dirty,’ war outcomes inflicted on populations during armed conflict.”

A month after the online publication of his critique of The Lancet’s 2006 Iraq study, Prof. Spagat posted a comment on his PLOS paper celebrating that NATO was now using the tool the IBC authors had previously recommended, in an adapted form called the ‘Civilian Battle Damage Assessment Ratio’ (CBDAR).

Spagat referred to a 2009 paper co-authored by himself, Hicks, and Ewan Cameron, a serving senior British Army official in Afghanistan, published in the British Army Review. Spagat described how this earlier work “was adapted to fit more productively with NATO military psychology and language, and to link directly with the existing military monitoring system of the ‘Battle Damage Assessment’ for ease of application.” Since October 2009, he wrote, the resulting “CBDAR methodology has been used by NATO forces in Southern Afghanistan… The methodology has identified a number of military activities that historically lead to civilian mortality that has led to NATO changing procedures.”

A quite different assessment is offered by Prof. Marc W. Herold of the Whittemore School of Business and Economics, University of New Hampshire, using a similar methodology to IBC. Herold, whose dossier on Afghan civilian deaths first inspired Sloboda and who is listed as a “consultant” to the IBC, found that in the period 2009 to 2010, deaths of Afghan civilians were not decreasing.

The myth of their decrease, widely reported in the media, has been supported by figures produced by the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA). But Prof. Herold documented that UNAMA, whose source data cannot be verified, undercounted Afghan civilians killed by coalition forces by 30% in 2008, and by 60% in 2009 — accounting for the supposed decline in civilian deaths trumpeted by Spagat. While in this period NATO forces decreased the use of indiscriminate air strikes, they replaced them with more deadly and secretive night-time special operations raids, which largely go unreported.

“The absolute number of Afghan civilians killed by foreign occupation forces is not declining,” wrote Herold in March 2010:

“The mainstream western media with few exceptions and organizations… de facto serve the Obama news management effort by severely under-reporting Afghan civilians killed by foreign forces.”

Since then, NATO’s appropriation of the Spagat and Hicks ‘death metric’ in Afghanistan has been deployed to great propaganda effect. While flawed UN figures documented a jump in violent incidents of 40% in the first eight months of 2011, NATO was citing its new DWI-based CBDAR ratio to claim that enemy attacks had dropped by 10% over the same overlapping period.

But the effort by IBC’s Hicks and Spagat to ingratiate themselves with NATO counter-insurgency efforts was the tip of the iceberg.

ORG’s Annual Report to the Charity Commission for the year ending 2009 confirmed that officials from the ORG Every Casualty research program, run by IBC directors Sloboda and Dardagan, had presented their proposals “in face-to-face private meetings with senior officials of several governments, including Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, and the UK.”

The following year, another British Army Review paper co-authored by IBC’s Sloboda and Dargagan with Col. Richard Irons, clarified that the recording of civilian casualties was seen as a tool to help NATO win wars by addressing the perceptions of local populations.

The “military stands to gain” from casualty recording, they wrote, because such openness “indicates that it respects locals enough to deal with them honestly.” Military-supplied casualty data can also be used to provide “a credible foundation to military claims… that they do all they can to reduce civilian casualties” — thus helping to justify military operations both at home and abroad.

Currently, there is no “convincing evidentiary base” to back up this claim, “but that base could easily be provided,” no doubt with the help of the IBC and its affiliated researchers. Most importantly, the ORG-IBC paper proclaims that there “are clear operational benefits to effective recording efforts. Modern operations recognise protection of civilians from insurgent coercion or intimidation as critical to success; hence one of the most important measures of effectiveness (MOE) of military operations is the level of civilian casualties.”

Rather than casualty recording being seen as a mechanism to end war, the IBC’s directors are selling casualty recording as a way to legitimize military operations, and increase the effectiveness of counter-insurgency responses to armed resistance.

IBC’s new metric to whitewash war-crimes

Yet far from offering an accurate picture of ‘dirty war’ atrocities against civilians, Spagat and Hicks’ DWI tool does the opposite.

PLOS Medicine senior editor Amy Ross points out that “the reliability of the DWI is tied to the reliability of the data sources available, which tend to be poor from areas of armed conflicts.”

Yet as other commentaries in PLOS Medicine showed, if data sources for DWI are largely unreliable and poor in the very areas of heightened armed conflict where civilian casualty tracking is especially needed, then the tool becomes exponentially more useless the more ‘dirty war’ violence is occurring.

Prof. Nathan Taback of University of Toronto’s Dalla Lanna School of Public Health explained in his PLOS Medicine article that a database of conflict incidents based on “secondary sources such as media reports or hospital records… inevitably leads to selection bias… the health effects of conflict upon civilians in the sample are not representative of health effects due to conflict in the civilian population as a whole.”

He adds that “many of the denominators” used in the Hicks and Spagat DWI calculations “such as total number of civilians injured, may not be readily available for most conflicts.” Inaccuracies in the total estimate would fatally compromise DWI assessments.

The most damning critique of DWI, however, comes from the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG), an interdisciplinary San Francisco-based network of statistical scientists analyzing conflicts, founded under the American Association for the Advancement on Science.

In a paper lead-authored by UN statistical consultant Prof. Amelia Hoover Green of Drexel University, HRDAG criticizes DWI as fundamentally misleading. Hoover et. al note that “accuracy claims about the DWI depend on the unmet assumption that rates of over- or under-counting (sampling bias) are equal across space, time, armed group and other dimensions.”

They point this out with a simple example. If only 25% of civilian deaths and 75% of combatant deaths are recorded, for instance, then the DWI measure would under-measure the proportion of ‘dirty’ incidents by half the true proportion. Other types of under-recording could lead to worse levels of inaccuracy.

The “accuracy and comparability of DWI statistics depend fundamentally” on the idea that data on violence is over or under counted equally across a conflict. But this assumption “is entirely implausible in a conflict situation. Reporting rates for violent incidents vary in complex and unpredictable ways within any given conflict: by region, by perpetrator, and by key victim characteristics such as gender, race, ethnicity and combatant status.”

The HRDGA team are particularly scathing on IBC’s favoured data sources:

“Passive surveillance systems, such as media reports, hospital records, and coroners’ reports, when assessed in isolation, lack even the benefit of a defensible confidence interval. Like most data about violence, these are convenience samples — non-random subsets of the true universe of violations. Any convenience dataset will include only a fraction of the total cases of violence… fractional samples can never be assumed to be random or representative.”

In a separate analysis by Patrick Ball and Megan Price of HRDAG, they point out:

“… we are skeptical about the use of IBC for quantitative analysis because it is clear that, as with all unadjusted, observational data, there are deep biases in the raw counts. What gets seen can be counted, but what isn’t seen, isn’t counted; and worse, what is infrequently reported is systematically different from what is always visible… As is shown by every assessment we’re aware of, including IBC’s, there is bias in IBC’s reporting such that events with fewer victims are less frequently reported than events with more victims.”

This does not mean that large events or events with more victims will always be counted. Especially large massacres committed by US forces in areas outside Baghdad, for instance, may be systematically overlooked, due to a dearth of media presence as well as censorship and editorial constraints on reporting.

Ball and Price go on:

“We suspect there are other dimensions of bias as well, such as reports in Baghdad vs reports outside of Baghdad. Small events are different from large events, and far more small events will be more unreported than large events. The victim demographics are different, the weapons are different, the perpetrators are different, and the distribution of event size varies over time. Therefore, analyzing victim demographics (for example), weapon type, or number of victims over time or space — without controlling for bias by some data-adjustment process — is likely to create inaccurate, misleading results.”

This analysis is set out in more detail in their recent paper in the SAIS Review of International Affairs.

This means that extrapolating general trends in types of violence from an IBC-style convenience dataset, which is inherently selective, is a meaningless and misleading exercise. It cannot give an understanding of the true scale and dynamics of violence. Yet this is precisely what IBC-affiliated researchers have been doing. That they have been able to publish these deeply misleading analyses in scientific public health journals is a disturbing indication of how little the academics sitting on the review boards of these journals actually understand the on-the-ground dynamics of conflict, and the statistical sleight-of-hand required to promote them as definitive.

It is not surprising that IBC’s DWI is seen as such a useful tool by NATO. The inherent inaccuracy built into the DWI means that it systematically conceals and obscures violence in direct proportion to the intensification of violence. In the hands of the Pentagon, DWI provides a useful pseudo-scientific tool to mask violence against civilians.

Hoover et. al write that:

“Perhaps the most analytically frustrating source of bias in violence statistics is violence itself: violent areas or situations are often inaccessible to human rights observers, government officials or other monitors, such that particularly extreme outbursts of violence may be severely underreported until well after the fact. Areas of extreme violence are likely to have high proportions of ‘dirty’ outcomes, and unlikely to be available for measurement. In this situation, DWI statistics would inflate the proportion of ‘clean’ outcomes, obscuring what they are intended to measure.”

In other words, DWI is particularly useful for the Pentagon in theatres where it is conducting “extreme violence” against civilians. The more civilians are killed in extreme underreported violence, the less likely they are to show-up via DWI-measures:

“Conflict may ‘reduce the numerator’ by annihilating an at-risk population, such that ‘dirty’ outcomes become decreasingly likely. Furthermore, members of the population at risk may choose to migrate or cease involvement in political activity as a result of earlier violence, decreasing both the numerator and the denominator. Thus, a stable or declining DWI may reflect the success of earlier dirty campaigns, rather than a true reduction in illegal strategies.”

Hoover et. al then provide empirical support for their demonstration of “the unreliability of various DWI measures, using data from El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia and East Timor.” In those cases, instead of offering an objective assessment of the conflicts, “DWI measures reflect the considerable errors and biases of the given single data source.”

Their final verdict is sobering:

“We question the basic utility and applicability of DWIs in the context of armed conflict. More generally, we argue that inattention to issues of bias promotes the over-confident, and therefore irresponsible, use of statistics in policy debates affecting human rights and human security.”

Yet the IBC went on to vindicate the utility of DWIs using its own database on Iraq, resulting in a 2011 study published in PLOS Medicine.

That paper by Hicks, Spagat, Sloboda and Dardagan, who were at the time funded by the US government-backed ORG Every Casualty program, concluded that although coalition forces had a higher dirty index rating than anti-coalition forces, “the most indiscriminate effects on women and children in Iraq were from unknown perpetrators firing mortars — with a dirty war index (DWI) rating of 79 — and using non-suicide vehicle bombs, with a DWI of 54, and from coalition air attacks, with a DWI of 69.”

No mention in the paper was made of the USIP funding received.

Their study thus conveniently fit the framework established by the USIP-convened Iraq Study Group: that most of the violence in Iraq was being perpetrated by sectarian insurgents. In an interview with Reuters, IBC’s Prof. Hicks further absolved US forces from moral culpability, stressing that coalition forces had not necessarily “killed more women and children, but that there was a high proportion of women and children among the civilians they killed.”

In other words, these IBC scholars, Spagat, Hicks, Sloboda, Dardagan, et. al — unwittingly or otherwise — were using their database to develop a metric that would permit NATO counterinsurgency operatives to accelerate and obscure civilian deaths.

Counter-insurgency shill in Colombia

Michael Spagat’s role as NATO’s numerical casualty sanitizer, based on the creation of a fundamentally flawed metric, is by no means the only interest of his that would raise questions about the integrity of his critique of The Lancet’s 2006 Iraq mortality findings.

From 2004 to 2007, Prof. Spagat received three grants totaling $334,135 from a little-known US defense contractor, Radiance Technologies, to develop databases on armed violence in Colombia and Mexico.

The Radiance website describes itself as a US weapons development and intelligence company providing “operational support for the Department of Defense (DoD), armed services, intelligence agencies, and other Government organizations… Radiance has repeatedly met the DoD’s increasing demand for innovative technology.”

Radiance’s ‘Intelligence Systems Group’ “proudly supports most of our nation’s intelligence community” including the Defense Intelligence Agency; US Cyber Command; National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency; National Reconnaissance Office; Strategic Command; Office of Naval Intelligence; the Army’s Intelligence and Security Command; the Air Force Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Agency; Special Operations Command; among others.

In the same period Spagat received this funding, Radiance Technologies was managing a controversial geographical research project on behalf of the US Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO), called ‘Mexico Indigena,’ which began in 2005 and ended in 2008.

Mexico Indigena was a prototype project of the American Geographical Society’s Bowman Expeditions, funded by the US Army’s FMSO, which “conducts analytical programs focused on emerging and asymmetric threats, regional military and security developments, and other issues that define evolving operational environments around the world.” The project was essentially a giant mapping exercise to support global US counterinsurgency planning.

“Indigenous peoples’ demand for land tenancy and territorial autonomy challenge Mexico’s neoliberal policies — and democracy itself,” warned Prof. Peter Herlihy and Prof. John Dobson, the academic administrators of the US Army-backed project in a July 2008 article published in Geographical Review.

Their project reports to Radiance Technologies also discussed “newly forming team[s] working in the Antilles, Colombia, Jordan and Iraq.”

In the preceding years, the US had backed considerable state violence against indigenous social movements. One movement organizer in Mexico, Aldo Gonzalez, head of the Union of Organizations of the Sierra Juarez, said: “The US military authorities who are behind the mapping project, have an interest in the privatization of communally held lands. Throughout their mapping investigations, they are seeking to understand the communities’ resistance to privatization and identify mechanisms to force them to join PROCEDE [a government privatization scheme]. Bowman Expeditions clearly state that they are collecting information so that the US government can make better foreign policy decisions.”

Naturally, that was not how the project was sold to the public. “FMSO’s goal is to help increase an understanding of the world’s cultural terrain,” opined Herlihy and Dobson on the project’s website to address growing concerns, “so that the US government may avoid the enormously costly mistakes which it has made due in part to a lack of such understanding.”

Not quite.

According to geographer Prof. Joe Bryan of the University of Colorado, Boulder, writing in his Weaponizing Maps: Indigenous Peoples and Counterinsurgency in the Americas (2015), the approach of this US Army-sponsored Radiance-run project was to draw on “research done by civilians” and compile “their findings into a database accessible to military personnel. Instead of focusing on war zones, this effectively turns all of society — all of the planet — into a potential battle zone… the Bowman Expeditions helped elevate counterinsurgency from a tactic to a strategy.”

Under the brand of his Colombia-based conflict think-tank, CERAC, Spagat and his CERAC co-authors published an extraordinary paper accusing Amnesty International (AI) and Human Rights Watch (HRW) of having “substantive problems in their handling of quantitative information.”

The alleged evidence for this was based on Spagat et. al checking AI and HRW written output against CERAC’s own “unique Colombian conflict database.” They drew the sweeping conclusion that both human rights organisations were guilty of “a bias against the government relative to the guerrillas,” and that: “The quantitative human rights and conflict information produced by these organizations for other countries must be viewed with scepticism along with cross-country and time series human rights data based on Amnesty International reports.”

As usual, Spagat et. al’s complaint was that their “massacre numbers… are almost always high” and that their assertions of systematic “government-paramilitary collusion” in perpetrating severe human rights abuses was thin. They claimed that just 3% of massacres committed between 1988 and 2004 in Colombia could be “definitively proved” to involve “government-paramilitary collusion.”

Sound familiar?

The paper acknowledged receiving comments from frequent Spagat co-author, IBC director Madelyn Hicks, among others, as well as funding from Colombia’s state-run Central Bank. It did not acknowledge that Spagat had received nearly half a million dollars from the same US defense contractor managing the US Army’s regional counter-insurgency mapping exercise.

Spagat’s anti-AI/HRW missive was thoroughly refuted in a detailed response by Prof. José Miguel Vivanco, director of HRW’s Americas division, formerly an attorney for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights at the Organization of American States (OAS).

HRW highlighted the statistical manipulation to produce the 3% figure:

“Here the paper introduces what appears to be a statistical distortion: the paper recognizes that HRW’s ‘main efforts’ to document ‘government-paramilitary collusion’ are two reports: The Ties that Bind and The Sixth Division, published in 2000 and 2001, respectively. But instead of comparing the documented cases in those reports with the total number of massacres committed in the years mentioned in the reports (mostly massacres committed in the late 1990s or 2000), which might have yielded a higher percentage of collusion in massacres, the paper compares them to the total of all massacres committed in ‘1988 to 2004.’ A more precise and useful analysis would have compared the documented cases of collusion for each year with the number of massacres in each year.”

In any case, the figure, HRW pointed out, is a statistical irrelevance:

“While we have done significant work on military-paramilitary links, this work cannot, as the authors seem to imply, be reduced to documentation of cases of direct military-paramilitary collusion in abuses. Rather, we have consistently described a much broader relationship, in which certain military units ‘promote, work with, support, profit from, and tolerate paramilitary groups.’… Although direct military involvement in abuses has occurred, toleration of paramilitary abuses has been the more chronic and intractable problem… The problem of toleration has been compounded by the generalized impunity for cases involving military collaboration with paramilitaries.”

Ultimately, regardless of the accuracy of Spagat’s 3% figure, “it says very little that is meaningful about the serious and complex problem of military-paramilitary ties.”

HRW concludes that although the organization is “accustomed to charges of bias” from “both government representatives and guerrillas… Rarely, however, are such charges dressed up so elaborately. Your paper’s extended analysis, complete with graphs and footnotes, gives it a superficial veneer of academic rigor. Yet closer scrutiny reveals serious and systemic errors in the analysis, which thoroughly undermine the value of the paper’s conclusions.”

USAID and CERAC

Spagat’s statistical sleights-of-hand on behalf of the US-backed Colombian regime are no accident. His Bogota think tank, CERAC, describes itself opaquely as being funded by “multilateral institutions and governments.” A significant quantity of this funding, however, comes from the US government (as well as the Swiss and Canadian governments).

The 2013 Annual Report for the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Colombia Human Rights Program III confirms that CERAC is among six sub-contractors funded by USAID in “support of human rights activities.” The total quantity of the program funding, and the specific amount granted to CERAC, has been redacted from the publicly released document.

The USAID document shows that its financial support of CERAC focuses on “situational analysis” including “baseline” and “monthly monitoring” assessments on “human rights violations and efforts to prevent and respond to these violations” — that is, building the CERAC database of violent incidents.

Like USIP, USAID is no impartial arbitrator in Colombian violence. USAID has given millions of dollars to Colombian paramilitary groups involved in drug-trafficking, all in the name of fighting the ‘war on drugs.’

“Plan Colombia is fighting against drugs militarily at the same time it gives money to support palm, which is used by paramilitary mafias to launder money,” said Colombian Senator Gustavo Petro. “The United States is implicitly subsidizing drug traffickers.”

In their seminal book, Cocaine, death squads and the war on terror (2012) Colombia scholars Dr. Oliver Viller of Charles Sturt University and Dr. Drew Cotton of the University of Western Sydney, show how the US government has fostered alliances with drug traffickers and paramilitaries, while propping up Colombian state repression and the cocaine industry.

Colombia’s paramilitary forces, they write, “function… as a vanguard force of the counterinsurgency strategy” on behalf of the US-backed regime to eliminate obstacles to foreign investment and corporate exploitation of resources, in the form of indigenous citizens inhabiting resource-rich land.

In the same period that Spagat’s research on armed violence in Colombia was funded by Radiance Technologies on behalf of the US Army, he and his CERAC team began producing papers claiming that lethal violence in Colombia was on the decline, due to the paramilitary demobilization initiated by the Colombian government to provide fighters amnesty and incentives for laying down arms. This work, according to Royal Holloway’s submission to the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise, was “used by the American Ambassador.”

But as Amnesty International reported:

“… the [paramilitary demobilization] process has abjectly failed to ensure that such fighters are genuinely removed from the conflict, that the paramilitaries and their backers are properly held to account for serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law, and to offer full reparation to the victims and their families. The collusion of sectors of the state apparatus, and some of those in business and politics, with paramilitary groups, and to a lesser extent with guerrilla groups and drugs-related organized crime, continues to pose a serious threat to the rule of law.”

CERAC’s US-government funded database of armed violence is derived in much the same way as IBC’s, through passive surveillance techniques monitoring “press, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations, research centers etc.” Needless to say, the notion that international and Colombian press (itself deeply compromised) report all violence in the country is difficult to take seriously.

It is not surprising, then, that Dr. Patrick Ball, executive director of the Human Rights Data Analysis Group, and his colleagues demonstrated that Spagat et. al’s consistent claims that lethal violence had declined in the wake of paramilitary demobilization were unsupported. Instead, Ball et. al found that “police reporting of lethal violence varies over time and across regions,” and that CERAC’s database likely undercounts total homicides.

CERAC’s triumphant declaration of a successful US-Colombian backed paramilitary demobilization program could even be concealing an increase in violence, explained Ball: “We show further that if the potential underreporting biases were corrected, the rate of homicides after the demobilization might be greater than the rate before the demobilization.” Spagat et. al’s “claims that homicides have decreased in the post-demobilization period likely rest on analytic artefacts that resulted from changes in the data collection process.”

And so we are left with the alarming conclusion that Spagat sits at the centre of a ‘virtuous circle’ of recycled statistical spin. While the US government funds CERAC’s inherently flawed database of human rights abuses, it then uses spurious pseudo-scientific extrapolations from CERAC to justify and vindicate its support for the Colombian regime’s ongoing human rights abuses.

Academia and US information operations

Prof. Spagat’s work as a US Army counterinsurgency sub-contractor has illustrious roots. From 1994 to 1996, Spagat received a ‘special projects’ $15,000 grant from the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) for research on the Russian transition to a market economy. Within the same period, he received a separate $55,000 grant from the National Council for Eurasian [formerly Soviet] and East European Research (NCEEER).

Both IREX and NCEEER are intimately related to US government propaganda operations.

IREX’s past Annual Reports show that its most consistent major funder is the US State Department. Its latest Annual Report shows that it’s other major funders include the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Swiss Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the US Agency for International Development (USAID), various US embassies, and USIP — the same agencies and institutions which fund IBC-affiliated researchers today.

From around 2005, the USAID Iraq Civil Society and Media Support Program funded IREX to create the National Iraqi News Agency (NINA) to “help Iraqi media outlets provide their audiences with impartial, accurate information.”

Privately, though, the US government had very different ideas. According to George Washington University’s National Security Archive, secret documents obtained under Freedom of Information showed that:

“American, British, and Iraqi media experts would be hand-picked to provide ‘approved USG information’ for the Iraqi public, while an ensuing ‘strategic information campaign’ would be part of a ‘likely 1–2 years… transition’ to a representative government… Defense Department planners envisioned a post-invasion Iraq where the US, in cooperation with a friendly Baghdad government, could monopolize information dissemination.”

NINA is now partnered with BBC Arabic, and functions variably as a mouthpiece for the Iraqi government and other powerful interests. A 2013 policy brief by BBC Media Action, the BBC’s international development charity, found that:

“The inability to find sufficient revenue from outside the donor community has led to a number of initiatives that were started with international support to either fall by the wayside or become subject to partisan influence following the conclusion of their international funding. The National Iraqi News Agency (NINA) set up by IREX with USAID funding offers a good case in point.”

Once NINA’s US government patronage expired, the agency solidified its relationship with the Iraqi Journalists Syndicate, which receives an annual budget of $7 million from the Iraqi government. In 2009, the Syndicate made a deal for its members to receive state lands at nominal prices “in return for positive coverage of government policies.”

So it is worth noting that Iraq Body Count recently told Foreign Policy that the IREX-founded NINA is “a reputable source.” IBC counts NINA among its key sources for violence in Iraq, among its top 12 media contributors out of over 200.

IBC has never expressed any concern about NINA’s lack of impartiality, which might affect its reporting on violent incidents, particularly those involving US and Iraqi government forces.

The other body that funded Prof. Spagat around the same time as IREX was the NCEEER, which also receives much of its funding from the US State Department. Its website boasts that its “support for research on this area has produced direct benefits for US policymakers” and “American business.”

NCEEER’s Board of Directors is staffed by two former senior State Department officials. The first, Richard Combs, was an advisor for Political and Security Affairs in the US Mission to the UN, before becoming a US-Soviet expert in the State Department.

But before his State Department stint, from 1950 Combs was chief investigator, counsel and senior analyst for Senator Hugh Burns’ Fact Finding Committee on Un-American Activities.

The Burns Committee was, according to the late Frank Donner — former director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Project on Political Surveillance — tied to a “network” of “patriotic, veteran, agribusiness, and right-wing” organizations.

In his classic history, Protectors of Privilege (1990), Donner reports that Combs was “venerated in political intelligence and countersubversive circles.” He secretly “orchestrated a network of informers… apprentice sources, investigators, and contacts cloaked in secrecy and intelligence hugger-mugger (drops, code names, safe houses).” It later transpired that Combs was keeping thousands of files on “a score of legislatures” in the House and Senate.

Combs’ anti-Communist witch-hunt, supported by US intelligence agencies, led him to target black people and Muslims in America. As documented by Indiana University historian Claude Andrew Clegg, in the Burns Committee’s eleventh report to the California legislature, Combs’ report found the “Negro Muslims” to be “un-American” purveyors of anti-white sentiment in schools for African American children.

Combs played a major role in inaccurate and unwarranted persecution of the black civil rights movement and the Nation of Islam, which was mischaracterized as a conduit for a “Communist conspiracy” fostering “progressive disillusionment, dissatisfaction, disaffection and disloyalty.”

The second former State Department official on the NCEEER board, Mary Kruger, had been a public affairs officer at the US embassy in Ukraine, and a consul general at the US embassy in St. Petersburg, Russia.

But Kruger was also, by the late 1990s, described as a “USIS representative” by the Sabre Foundation, a charity which donates millions of dollars worth of books to “transitional countries.” Sabre receives most of its funding from the US State Department, USAID, and US Information Agency.

USIS, of which Mary Kurger was an employee, is the United States Information Service, a foreign cultural arm of the US Information Agency (USIA). USIA’s mission according to the 1999 Foreign Affairs and Restructuring Act was “to understand, inform and influence foreign publics in promotion of the national interest.”

During the Cold War, the USIA mobilized a wide range of media instruments, including books, magazines, and radio, to counter Soviet propaganda with the US government’s own propaganda around the world. After 1999, the USIA was closed down, and its functions shifted to the State Department.

From 2008–2009, the Sabre Foundation, which had been funded by the USIA under Mary Kruger’s tutelage a decade earlier, received “$50,000 and over” from the US State Department for Iraq, according to Sabre’s Annual Report for that period.

Spagat’s early career connections to IREX and NCEEER, both conduits for US State Department propaganda operations, as well as to Radiance Technology, USAID, and USIP, raise serious ethical questions, as well as questions about the reliability and impartiality of his work, and that of IBC.

This tapestry of connections between IBC affiliated researchers and the militaries of key NATO members, demonstrates that IBC’s characterization of itself as an independent anti-war group doing reliable and credible research on civilian casualties is false.

On the contrary, over the last decade, IBC has increasingly found itself, its data and its questionable research methods willfully co-opted by the very governments prosecuting the wars it claims to oppose.

2 — The Pentagon’s Iraq mortality pseudoscientist

In his paper published in Defence and Peace Economics in 2010, Prof. Spagat reaches the startling verdict that the 2006 Lancet survey “cannot be considered a reliable or valuable contribution to knowledge.” Yet close analysis reveals the same types of analytical sleights-of-hand he has perpetrated for the Colombia conflict.

In what follows, I interrogate the specific arguments of Prof. Spagat’s landmark critique of the 2006 Lancet survey, to explore whether they really support that conclusion.

AAPOR

Spagat’s first line of attack was in the observation that the Lancet study was in breach of several rules in the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Code of Professional Ethics & Practices. He followed this up with scrutiny of the questionnaires used and the overall study design. This is perhaps the most compelling element of Spagat’s critique, and contains valid points. However, their implications are over-stated.

As the Washington DC-based doctors group, Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) pointed out in its report last month, “the Lancet authors are not even members of the association,” and so were under no ethical obligation to adhere to its rules.

Disclosure

In particular, Spagat cited AAPOR to claim that the study’s lead author Prof. Gilbert Burnham has unreasonably refused to make either questionnaires or the data for the study available for inspection.

Yet Spagat ignored the fact that, according to the New Scientist, “Burnham has sent his data and methods to other researchers, who found it sufficient.” In fact, Burnham, New Scientist reported, had been told by his superiors at the John Hopkins Bloomberg School “not to supply AAPOR with the requested additional material since neither Burnham nor the Bloomberg School are AAPOR members, and therefore AAPOR had no right to play judge in this case.”

One main reason all the data has not been made available to others is because, as Spagat points out, in some cases the actual questionnaires used contained identifying markers. Their release, as the PSR report also notes, would have violated confidentiality. These identifying markers should not have occurred as a matter of ethical procedure, but had been missed by the lead researchers due to language issues. Bloomberg School censured Burnham for this error, but noted that no one had been harmed precisely because Burnham had ensured that the data itself was kept confidential and not simply handed out to the wider scientific community.

Spagat’s insinuations regarding potentially nefarious motives for not fully disclosing all the data, departed fundamentally from the conclusion of the Bloomberg School’s internal investigation of the study, which he himself cites only selectively.

After a careful review of the 1,800 original questionnaires, the Bloomberg School investigation concluded that the questionnaires were indeed authentic, and found no evidence of falsification, fabrication, or manipulation: “The information contained on the forms was validated against the two numerical databases used in the study analyses. These numerical databases have been available to outside researchers and provided to them upon request since April 2007. Some minor, ordinary errors in transcription were detected, but they were not of variables that affected the study’s primary mortality analysis or causes of death. The review concluded that the data files used in the study accurately reflect the information collected on the original field surveys.”

Doorsteps

Spagat goes on to make much of the ethical conundrums of the Lancet team interviewing Iraqis on their doorstep, which he speculates would have put them at risk from local militias:

“Approaches to potential respondents were essentially public events at the local level and could often have been known by local militias or criminals. A person could answer the door and refuse to be interviewed but he or she might still not be able to demonstrate to intimidating observers that he or she had truly refused. Local militia members, for example, may have simply assumed that someone who had been approached by the survey had disclosed information detrimental to the interests of the militia. Such an individual might have suffered simply from answering the door, regardless of whether or not he or she had actually consented to be interviewed.” [emphasis added]

Spagat’s critique is replete with this sort of speculative conjecture. I asked several Iraqis who had lived in the country during the post-invasion period what they thought of Spagat’s criticisms, and they all agreed that they were largely irrelevant.

If Iraqis felt they should not conduct doorstep interviews due to fears regarding safety, they said, they would simply not answer the door. The fact that interviews were conducted on doorsteps in this manner itself demonstrated that the respondents themselves were perfectly comfortable with conducting the interviews in a relatively public context. Given that Spagat fails to provide any actual evidence that the procedure resulted in anyone coming to harm, it is not clear that the procedure in fact posed any risk. If it had done, Spagat should have been able to substantiate this by pointing to evidence of the risk materialising in actual harm. Since he did not, this suggests that the risk was indeed minimal, a notion supported by the Iraqis I spoke to.

The concern for confidentiality is a reasonable question, but there is no simple solution: If interviewers insisted on being permitted to enter homes, or did not establish that sort of climate of trust, it could have generated other unacceptable security risks for both the research team and respondents.

Neighbourhood trust-building

Spagat also made much of the fact conceded by Lancet authors Burnham and Roberts that to minimise risks to the interviewers, they allowed locals, including children, to inform the wider neighbourhoods of their presence, and wore white-coats to identify themselves.

For Spagat, this created the following problem:

“By encouraging neighbours, with a particular emphasis on neighbourhood children, to explain the purpose of the study, the field teams set in motion uncontrollable dynamics that may have distorted the perceptions of L2’s [Lancet 2006] potential respondents. It is no longer possible to reconstruct how individual participants, many of whom would have first learned about the study from a neighbour (adult or child), understood the purpose of the study at the moment they consented to be surveyed.”

Yet as Burnham explained, the sole purpose of informing locals and children within “a cluster of houses close to one another” was to ensure that it was understood that they were not affiliated to any militias, or the government, but were neutral scientists conducting a survey. In any case, the specific purpose of the survey was explained directly to respondents before consent was received. Spagat raises speculative questions, but once again provides no actual evidence to suggest that this procedure either endangered locals or fatally distorted perceptions of those surveyed.

On the contrary, the Iraqis I interviewed, who are personally familiar with the tense environment of the time, said that this procedure would have greatly aided the research team in establishing trust with the local communities to obtain access to households. Spreading the word among locals and children within particular household clusters would have helped assure potential respondents that their intention was indeed benign, and had no relationship to local sectarian or governmental interests.

White-coats

The use of “unusual” white-coats, Spagat says further, in such a public context would have undermined the confidentiality of the interviews. However, he overlooks the fact, as my Iraqi sources explained, that by spreading the word of the survey relatively in advance, the research team established a local climate that was far more conducive to the safety of respondents in the event that they agreed to conduct the doorstep interviews. Ultimately, locals themselves would have been far more aware of potential local risks than the interview team, and this procedure gave them the opportunity to decide whether they were comfortable or not with being interviewed.

As above — the concern for confidentiality is a reasonable question, but there is no simple solution: If interviewers insisted on being permitted to enter homes, or did not establish that sort of climate of trust, it could have generated other unacceptable security risks for both the research team and respondents.

All the points raised here by Spagat offer valid questions about how to improve such procedures and minimize risks in conflict environments, and suggest that more could have been done. On the other hand, Spagat ignores that in the context of the conflict there were inevitably trade-offs to be made. Ultimately, though, most of his criticisms are speculative and based on theorizing risk dynamics without evidence or understanding of the actual nature of militia activity in Iraq.

George Soros

Surprisingly, given Spagat’s own systematic reticence in disclosing his own conflicts of interest and funding sources, he alleges that the 2006 Lancet authors failed to disclose that their research was funded by the Open Society Institute (OSI) of George Soros. Spagat quotes an article in the National Journal which reported that OSI funds had come through the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

But Spagat here repeats a falsehood disproved two years earlier. As MIT’s John Tirman told the British journalism watchdog Media Lens in January 2008:

“Open Society Institute funded a public education effort to promote discussion of the mortality issue. The grant was approved more than six months after I commissioned the survey, and the researchers never knew the sources of funds. As a result, OSI, much less George Soros himself, had absolutely no influence over the conduct or outcome of the survey. This was told to the authors of the National Journal article at least twice. One must conclude that their misrepresentation of this — among many other issues — was intended to sensationalize their version of the story and color the readers’ opinion about ‘political bias.’ This is contemptible malpractice on their part.”

The survey had been commissioned long before the Open Society Institute funding, with internal funding from MIT’s Center for International Studies. Further, the OSI funding had nothing to do with supporting the actual survey or funding its research. Correspondence between Tirman and the author of the National Journal article, Neil Munro, obtained by Media Lens proved that Munro had been fully aware of these facts, but went ahead and printed his falsehood anyway.

Despite this being in the public record for years, Spagat went ahead and further repeated Munro’s falsehood despite its being discredited.

Data entry

While independent experts and the Bloomberg School’s own internal investigation all confirmed that the questionnaires used for the survey were entirely appropriate for the research, Spagat — who unsurprisingly was not granted access — managed to obtain “the English-language list of questions and a data entry form” from Munro, who claims to have received them from “a third party who had apparently obtained it from an L2 author.” He then subjected these to a critique.

Every source in this chain is questionable: Spagat himself, whose conflicts of interest and vested interest raise all sorts of questions; Neil Munro, who demonstrably lied in his National Journal article; and the unidentified “third party” who supposedly obtained these materials from an unidentified Lancet author.

Spagat spends some time picking apart the form trying to prove that inexact wording would lead to imprecise questions and, therefore, potentially misleading answers. All this is irrelevant, though, because Spagat is ultimately analysing materials he obtained from a journalist who deliberately reported a falsehood to defame the study in question. There is no independent evidence proving that what he is analysing had anything to do with the Lancet survey.

Main street

After raising these ethical questions, Spagat attempts to get substantive. He reiterates the ‘main street bias’ argument, which argues that as most of those interviewed were families residing on main streets, this would lead to an overestimate of deaths because families were at greater risk of violence on main streets as opposed to anywhere else.

Spagat references an earlier paper where he and his co-authors attempt to show that main street bias could lead to overestimates by a factor of 3. But a working paper version by Spagat putting forward the same argument was quickly demolished by science blogger Dr. Tim Lambert of the University of New South Wales, who writes for National Geographic’s scienceblogs.com.

Lambert pointed out, citing a conversation between Prof. Stephen Soldz and Dr. Jon Pedersen — head of research at the Fafo Institute for Applied International Science — that “if there was a bias, it might be away from main streets [by picking streets which intersect with main streets].” Pedersen, Lambert noted, “thought such a ‘bias,’ if it had existed, would affect results only 10% or so.”

The biggest problem with the main street bias argument is the strange presumption that most Iraqis were killed at their homes on main roads. Spagat et. al fail to provide any evidence for this presumption beyond frivolous speculation, and references to IBC data. The latter, as seen above, is deeply selective and cannot offer any basis to extrapolate trends of violence that are not simply statistical artifacts, as Ball et. al have proven decisively.

Once again, Spagat and his colleagues rely on their own ignorance of the real dynamics of the Iraq conflict on-the-ground, and the credulity of readers who are looking to the experts for that sort of insight.

As the Lancet authors rightly point out, most violence in Iraq occurred in public spaces. A car bomb exploding in a market, for instance, would injure and kill people from throughout the neighborhood. Attacks consisted of air strikes, random shootings, shelling, raids, and death squad assassinations. Iraqis were killed on rooftops, on roadsides, at check-points, in markets, shops, as well as in their homes. The assumption that violence was concentrated disproportionately to target homes on residential main roads should never have made it into an academic journal.

As Lambert concluded, “the only way” Spagat et. al were able to make ‘main street bias’ significant as a “source of bias was by making several absurd assumptions about the sampling and the behaviour of Iraqis.”

Success rate

Following from the main street bias theory, Spagat’s next move is to compare the 2006 Lancet’s success rate in finding respondents at home for interview, to the success rate for previous studies — primarily, the first 2004 Lancet study; a UN Development Program survey conducted in partnership with the Iraqi Ministry of Planning and Development Corporation, called the ‘Iraq Living Conditions Survey’ (ILCS); and a survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) with the Iraqi Ministry of Health (MoH), the ‘Iraq Family Health Survey’ (IFHS).

He argues that since the 2006 Lancet survey reported a very high success rate, while the previous surveys had a lower success rate, something must be amiss: in the period between the older and newer surveys, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis fled or were displaced, so we would expect that the research team would be less successful in finding people at home to interview, not more. He then attempts to quantify the odds of the Lancet’s claimed success at finding more respondents at home than the other studies. Those odds are at least “190 to 1,” and more likely “nearly 100,000 to 1.”

Spagat concludes:

“… these comparisons provide some evidence of fabrication and falsification both in L2’s reported success rates in visiting selected clusters and in L2’s reported contact rates with selected households.”

Ironically, the most obvious explanation for the higher success rate of the Lancet authors is mentioned by Spagat himself. As the research team made a point of giving locals within a certain cluster of households a degree of advance notice to increase trust and minimize risks to the research team, they increased the probability that locals would choose to be at home. This easily explains why the 2006 Lancet study, the only Iraq death toll survey to have used this procedure, had a marginally higher response rate than the other studies.

This example in itself demonstrates the specious nature of Spagat’s critique. Based on unfounded assumptions and generalizations, the ‘improbabilities’ he calculates as evidence of falsification or fabrication are themselves merely statistical artifacts that ignore the complexities of the real-world.

The other issue, of course, is his curious selectivity. Spagat uses other studies as a baseline for normality, but fails to subject their methods to the same level of scrutiny. He therefore has no idea whether those studies offer an accurate baseline.

As noted in a paper led by Prof. Christine Tapp of Simon Fraser University published in the journal Conflict and Health, there were significant limitations with the ILCS. The survey was “conducted barely a year into the conflict,” had “a higher baseline mortality expectation, and differing responses to mortality when houses were revisited.” Tapp et. al note that criticisms of the study acknowledged by its authors, which Spagat ignores, include “the type of sampling, duration of interviews, the potential for reporting bias, the reliability of its pre-war estimates, and a lack of reproducibility.”