Everywhere we look we see multiple, overlapping crises accelerating at exponential rates - climate-related disasters, a pandemic, war in Europe, cost of living, energy and food scarcity, to name just a few.

As these crises intensify anxiety, uncertainty and suffering the world over, it’s becoming increasingly obvious that conventional solutions are no longer working. Politicians have few persuasive answers. Existing institutions are overwhelmed. There is a rising sense of disillusionment and apathy about the future.

But in reality, as we move through the eye of the needle, humanity is on the cusp of something momentous. The story that you’re not being told, that most conventional analysts and institutions fail to recognise, is that we are on the verge of the next great leap in our evolution as a species; that there is a future we can build together well within reach – a bright future of abundance, regeneration and prosperity for all.

And the strangest thing of all is that the frightening trends we're seeing escalate today are actually signs of that emerging future.

Global civilisation is in the throes of a fundamental transformation of unprecedented scale. As the warning signals of the global climate and ecological emergency sound louder and louder, it’s only by recognising this new possibility space – and moving toward it as rapidly as possible – that we can navigate this age of transformation and reach a desirable destination.

The old system is falling away. A new system is being born. Exponential crises are racing head-to-head with exponential technologies which could provide us the levers for total transformation. Yet neither crises, nor technologies, will ultimately determine our fate - that will be a question of our choices, our values, our worldviews, our organising structures, and beyond.

Change is inevitable: but the destination is not. The future rests on the knife-edge of what we choose today.

With the right choices, some of the most robust scientific data available is showing us how we can leave the era of scarcity and conflict behind us. And we can do it far more quickly and cheaply than most politicians and pundits would have you believe.

But it will be all too easy to be derailed by the wrong choices. To avoid that, we need to understand the complex interplay between the massive rise in polarisation today that we see across our politics and culture, and our distance from the earth itself.

The new authoritarian normal

Over the last decade or so, if not longer, Western politics has shifted relentlessly toward the normalisation of authoritarianism. Britain’s exit from the European Union in 2016 was just one key moment in this wider process in which the liberal heartlands of Western democracies have increasingly absorbed and mainstreamed the once marginal politics of the far-right.

But this process has not come out of the blue. It’s intimately related to a deeper and wider earth system crisis that reveals how the overarching systems that define global civilisation are crumbling under their own weight.

I had anticipated this abrupt shift in the Western political system back in 2010. That year on 6th May, the Conservative Party took the reins of power for the first time since 1992, propped up with some help from the Liberal Democrats.

Hours before the election result, I warned that whichever government was elected, it would be “unable or unwilling to get to grips with the root structural causes of the current convergence of crises facing this country, and the world”. This would therefore be the first step in a dramatic shift toward the far-right that would likely sweep across the Western world within 5-10 years, culminating in “the increasing legitimisation of far-right politics by the end of this decade”.

The global shift to the far-right began within five years of my forecast, and continued to accelerate through to the end of the decade.

Human system destabilisation: The shift to extremes

In 2014, far-right parties won 172 seats in the European Union elections — just under a quarter of all seats in the European Parliament. In 2015, David Cameron was re-elected as Prime Minister with a parliamentary majority, based largely on his nationalist populist promise to hold a referendum on Britain’s EU membership.

The following year in June, the ‘Brexit’ referendum shocked the world with a majority vote to leave the EU. Six months later, billionaire real estate guru Donald Trump shocked the world again when he became president of the world’s most powerful country.

Like the Conservatives in the UK, the Republicans had forged trans-Atlantic connections with European parties and movements of the extreme-right.

Since then, far-right parties made electoral gains across Europe in Italy, Sweden, Germany, Austria, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Poland, Hungary and elsewhere. The election of the Biden administration did not fundamentally change this abrupt and permanent shift in the nature of Western politics. The genie is now out of the bottle. Far-right politics is no longer the province of the fringe, but has become a staple of power.

The rapid, sudden shift in American, British and European national attitudes was the cumulative result of a complex chain of causality stretching from the Middle East and North Africa, where the profound impacts of a deep crisis in the earth system was unfolding beneath the radar.

In 2016, Europe was experiencing a massive, unprecedented surge in migration like nothing it had ever seen before, from war-torn countries including Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya and beyond. Many of these migrants were attempting to cross into the UK, even as Britain was experiencing a large wave of immigration from Eastern Europe. The preceding year, 1.3 million people had arrived on Europe’s shores requesting asylum, the highest number since the Second World War. The vast majority of the asylum-seekers (nearly half) were Syrian, with a fifth from Afghanistan and a tenth from Iraq.

The series of wars that escalated across these regions was instrumental in the capacity of politicians like Nigel Farage to mobilise the politics of fear into a political victory. Far more than any other concern, anxiety over immigration played a pivotal role in the Leave vote, helping to reinforce the growing breakdown of trust with incumbent politicians.

According to the British Social Attitudes survey, 73% of Britons expressing fears about immigration voted Leave.

The xenophobia around the Brexit campaign even played a crucial role across the Atlantic in Trump’s 2015 election campaign. In ads promising to end “massive illegal immigration”, Trump’s campaign brazenly used images of Syrian refugees traveling through Hungary to Austria in September that year. Trump had even called himself “America’s ‘Mr Brexit’”, and promised that his coming election victory would amount to “Brexit times 10.”

But the drivers behind the migration which populist politicians used in their campaign propaganda trace back to the sudden, rapid descent of parts of the Middle East into protracted conflict.

Earth system disruption: Syria

Among the underlying triggers for the pulse of regional violence that was centred around Syria was a convergence of energy and climate crises.

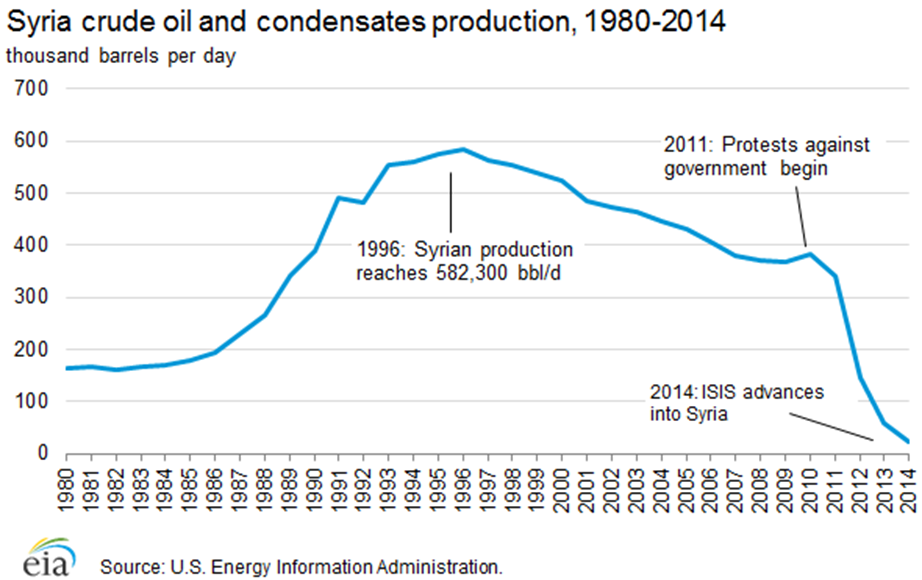

From 2001 to 2009, Syria’s oil production had declined by a third from 581,000 barrels per day (bpd) to 375,000 bpd. The decline had started around 1996, when its conventional oil production had peaked.

As a result, a country that had once been a net oil exporter suddenly found that one of its most crucial sources of state revenue was haemorrhaging. By 2014, Syria’s oil production had largely collapsed – the same year that the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) advanced into the country.

The collapse of Syria’s oil revenues eroded the government’s capacity to manage domestic crises, especially from mounting agricultural challenges exacerbated by water scarcity. From 2007 to 2010, Syria was experiencing a natural drought cycle whose severity had been greatly amplified by climate change. According to one major study, this was one of the worst droughts on record in the country. The drought exacerbated neoliberal agricultural mismanagement, culminating in widespread crop failures.

Although some have argued that the role of climate change in the drought has been overplayed compared to Assad’s mismanagement, one of the world’s foremost experts on global water and climate issues, Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute, has concluded that the role of climate change in amplifying drought conditions and driving migration, even if it interacted with other issues, cannot be denied.

Since then, other scientists have corroborated Gleick’s view with more extensive data. In 2018, a team of Austrian scientists decided to test the claim that climate change was actually causing people to migrate in Middle East conflicts, including Syria.

Publishing their findings in Global Environmental Change, one of the most respected journals in the field, they described how they had examined an exhaustive dataset of asylum-seeker applications for 157 countries. Their research uncovered a clear empirical connection between migration trends and regional countries facing climate-linked conflicts.

From 2010 to 2015, they concluded, climate change drove long-running droughts which exacerbated local and national tensions, and laid the groundwork for political violence that culminated in people fleeing their homes for safety.

“Our results indicate that climatic conditions, by affecting drought severity and the likelihood of armed conflict, played a significant role as an explanatory factor for asylum seeking in the period 2011–2015,” they wrote.

Differences in the severity of drought episodes… are able to significantly explain differences in the onset of conflict in the period between 2011 and 2015.

The onset of droughts exacerbated by climate change was particularly powerful in explaining the “emergence of armed conflict in the context of the Arab spring and the Syrian war, in addition to war episodes in Sub-Saharan Africa” from 2010 to 2012.

In other words, the sequence of conflicts that erupted in the wake of the ‘Arab Spring’ was not just a political crisis. It was, fundamentally, an earth system crisis.

In Syria, as crops collapsed around 2007, tens of thousands of primarily Sunni farmers from the south migrated with their families, desperate for new work and homes, to Syria’s coastal cities. The latter were dominated by the Ba’athist Alawite classes linked to the Bashar al-Assad regime.

The influx stoked simmering sectarian tensions between the Sunni working class and Alawite elite. As Syria’s oil export revenues evaporated, so did Assad’s appetite for public spending. He slashed government fuel and food subsidies which were so indispensable for keeping domestic prices affordable in a country with a huge and rapidly growing population of impoverished young people. But doing so cut off the last lifeline for millions.

When protestors hit the streets in wave after wave, Assad decided to respond with intensifying brutality. Some took up arms against the regime. Taking a leaf out of George W. Bush’s book, Assad declared that he was simply fighting ‘terrorists’, and scaled up the police and military response. The result was an escalating cycle of violence that became a recruiting sergeant for regional extremists, sucking in a diverse array of armed groups including Islamist militants from Iraq.

As the conflict intensified, international geopolitics reared its ugly head. The US, Britain, France and other European countries, the Gulf states, Turkey, Iran, Russia and even China – all saw Syria as a highly strategic location for the future of the region. And so they began throwing money, millions and eventually billions of dollars, at their favoured factions in the conflict. As Syria descended into internecine warfare, the remnants of al-Qaeda in Iraq metamorphosed with other groups and turned into the so-called ‘Islamic State’.

The rise of ISIS escalated regional conflict, led to a spate of Islamist terrorist attacks in the UK and Europe, and stoked the global ‘war on terror’. Muslim minorities in the West came under renewed scrutiny from media, police and national security agencies. As Syria’s war intensified, the collapse of much of the country’s infrastructure drove hundreds of thousands to flee.

And so we come full circle. By the time of the Brexit referendum, a million people, nearly half from Syria, had arrived on the shores of Europe, desperate for a safe haven from the devastation and terror they were witnessing at home.

They had travelled thousands of miles across vicious terrain and harsh waters, unsure of whether they would live or die, certain only that they could not go back. But their arrival in Europe threw another match to the flames.

Their presence became cannon-fodder for anti-immigrant and far-right movements, accelerating the rise of a new nationalist politics across the Western world that culminated in the rise of Trump in US and Brexit in the UK.

The earth system chaos that had erupted in Syria was not contained in Syria. It resulted in a string of polarising geopolitical disasters, crowned by the permanent transformation of the very heartlands of Western liberal democracies.

A global crisis

Yet the Arab Spring and even the climate shocks that preceded it represent only one facet of the story. The turning point in the global system that most of us will be familiar with occurred a few years earlier, in 2008, with the global financial crisis. The sudden collapse of the banking system, beginning in housing markets and rippling across the world, took most governments and financial institutions by total surprise.

Like the authoritarian turn in Western politics, I had been expecting it. On 20th November 2007, I had delivered a lecture at Imperial College, University of London, predicting an imminent collapse of the global banking system that would begin in the housing sector due to the unravelling of unsustainable levels of debt. Existing macroeconomic tools would be unable to solve or forestall the crisis, I’d said.

Yet it was the preceding year that I’d first become alive to the risk of an impending global economic collapse.

“US financial analysts privately believe that ‘a collapse of the global banking system is imminent by 2008’”, I reported in August 2006 - about a month before Nouriel 'Dr Doom' Roubini famously warned of an impending global financial crisis at the IMF.

I was recording the contents of an extraordinary meeting I’d had that month with a top Pentagon advisor who had high-level connections to the Washington military, financial and intelligence establishment.

Sitting in a quiet corner of the hotel lobby during his visit to London, we sipped afternoon tea and ate fine biscuits while the official spoke of a coming convergence of energy, climate and economic crises that was about to derail the stability of the international system. The official described how he had been told privately by US financial analysts that “a collapse of the global banking system is imminent by 2008.” Although the contagion would be centred around the housing markets, he said, one of its major triggers would be an energy crisis.

Although most conventional economists don’t recognise it, he explained, the health of the global economy is intimately connected to the global energy system. Energy is the bedrock of all economic activity – because all material flows enabled by the movement of economic wealth are ultimately dependent on the availability of energy.

The growth and expansion of industrial civilisation over the last two hundred years has been partly enabled by the exploitation of cheap, abundant energy derived from fossil fuels, at first in the form of coal, and later from oil and gas.

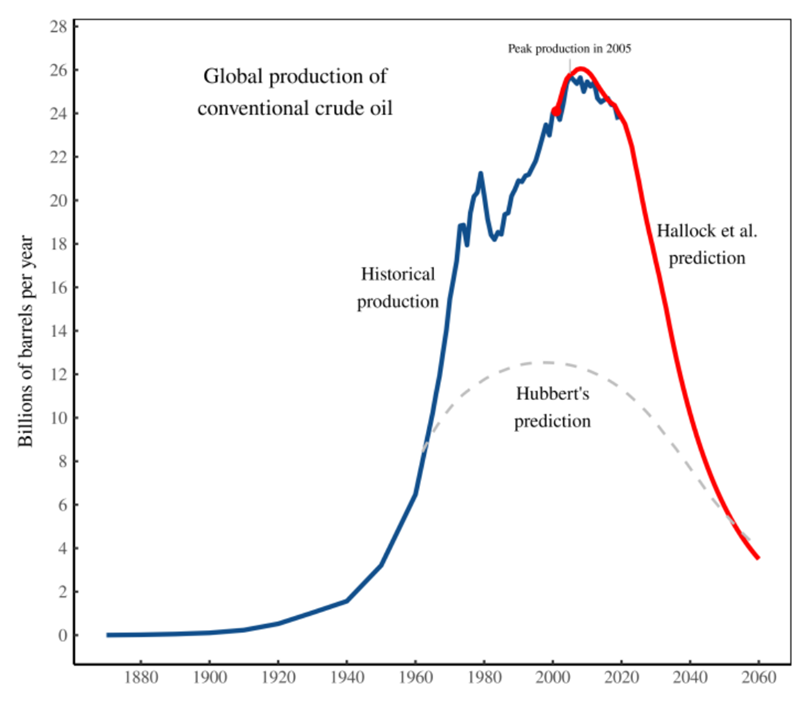

But around 2004 to 2005, something deep had shifted in the global energy system. The global production of cheap, conventional oil appeared to have hit a ‘peak’. Instead of continually growing, production had started to slow, cap off, and was now plateauing. Oil industry experts say that a resource ‘peaks’ in production at roughly the point when half its reserves are depleted. After that point, the rate of production gradually tapers off.

“Global oil production most likely peaked two years ago”, the Pentagon advisor told me.

In fact, it wasn’t all oil production that had peaked, only the cheapest kind that is easiest to extract, known as ‘conventional’ oil.

As Sir David King, the UK Government’s former chief scientific advisor, clarified in a recent study, this peak did not mean that we are running out of oil. It reflected that as we are now shifting to more difficult-to-extract sources, we’re using more energy just to get the oil out, leaving us with less for wider society.

According to Toronto-based political economist Dr Blair Fix, the current plateau and decline of conventional oil production has closely tracked a peer-reviewed model produced by Dr John Hallock Jr of the New York State Department of Transportation.

As a result, oil prices had begun to rise dramatically, getting higher and higher as production shifted to more expensive forms of unconventional oil, like shale. The Pentagon advisor believed that price spikes would have a recessionary effect helping to trigger an economic crisis.

He was right. The conventional view is that the 2008 financial crisis was all about a meltdown in housing markets which had over-borrowed. This is only partly true. As Professor James Hamilton, an economist at the University of California, told the US Congressional Joint Economic Committee in 2009, it was the global oil crisis that punctured the housing bubble.

From 2005 to 2007, as total world oil production declined for the first time in history, demand for oil continued to boom driven by huge growth in GDP. From 2004 to 2005, GDP rose 9.4 percent. Then from 2006 to 2007, it rose another whopping 10 percent.

As rocketing demand hit the ceiling of dwindling supply, oil prices doubled between June 2007 and June 2008. This drove up costs of living to unaffordable levels. Consumers stopped spending – they couldn’t afford to – and as their ability to afford things suddenly deteriorated, so did their capacity to sustain debt-repayments.

And it wasn’t just oil. With energy as the bedrock of the economy, the oil price spikes drove up costs of everything. Manufacturing, transport, construction, food and beyond. So when the housing bubble burst due to the unravelling of huge build-ups of debt coupled with all manner of shady financial practices, this was just the beginning.

The global banking collapse coincided with a sequence of intensifying climate events all around the world. From 2008 to 2011, every major food-basket region experienced devastating extreme weather events that crashed their ability to keep growing some of the world’s most critical staple crops, such as wheat and corn. The resulting global shortages drove food prices up to record levels. With both oil and food prices spiking at an unprecedented scale, financial speculators rushed in to scoop up lucrative shares in oil and food commodities. This further hiked up prices even further.

In many parts of the world, the oil and food price spikes led to unbearable levels of impoverishment. Across the Middle East and North Africa, people could not afford to buy basic staples such as fuel or bread. Toiling in regimes of repression, these brutal economic conditions were a match to the flames.

That’s why at the time, scientists at the New England Complex Systems Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, concluded that the Arab Spring was effectively a giant, regional food riot, driven by rampant commodity speculation. The sudden jump in food prices was so sharp, it triggered scarcity on the ground in many Arab countries heavily reliant on food imports. When the Tunisian street food vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set fire to himself in December 2010 in an act of supreme despair and defiance, it resonated with people across the region. By early 2011, the Arab world was aflame.

That verdict probably went too far, ignoring how the food crisis amplified long-simmering political tensions and economic problems - but it highlighted the role of the global food system and a deeply unequal economy in tipping over highly fragile systems into a series of cascading crises.

Institutional blindness

When crises in the earth system erupted, the human system was overwhelmed, too caught up in grappling with the rapidly crumbling mountains of debt that were tearing down institution after institution in a ruthless, indiscriminate avalanche of economic destruction.

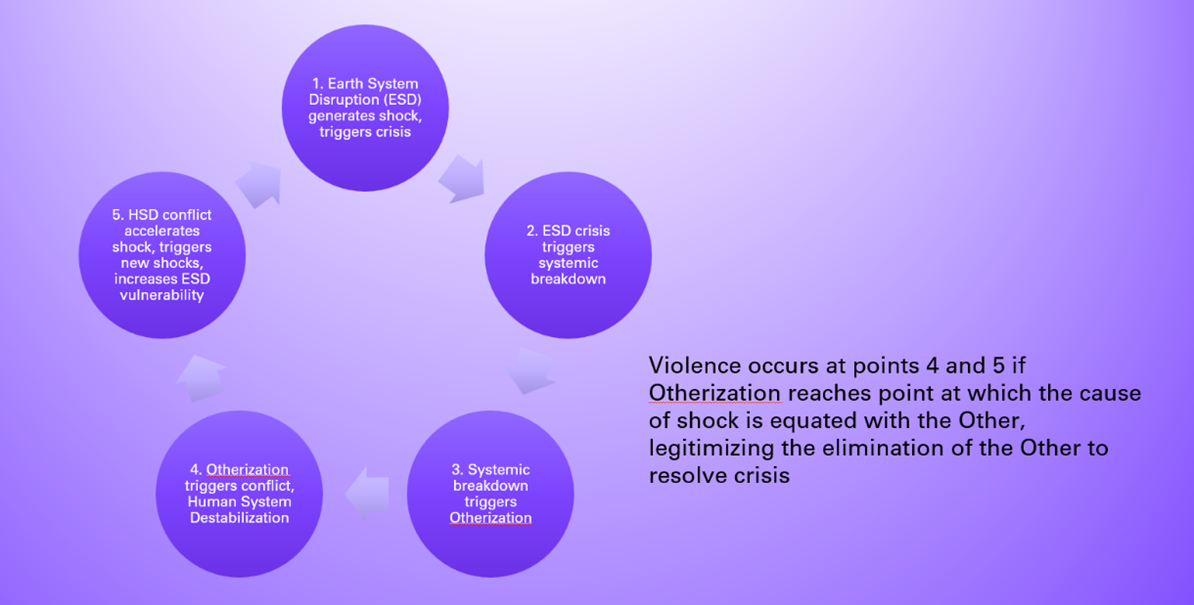

The energy, climate and economic crises unfolding on a global scale were simultaneously erupting from within at regional, national and local levels. In many ways, what had unfolded in Syria was merely a microcosm of what was happening on a macro-scale to the global system.

If any of this sounds familiar, it’s because it is. All the data today suggests we are entering another similar energy, climate, food and economic crisis convergence cycle.

Our institutions do not, by and large, recognise what is happening. Instead, our political and media leaders respond to the surface symptoms of crisis – hordes of people arriving at the doorstep – rather than to its root, systemic causes.

Earth system disruption across climate, environment, energy and food is driving the destabilisation of human social, economic and political systems. In turn, the destabilisation of those systems has inhibited our capacity to recognise and respond to what’s going on in the earth system. The result is that we become even more vulnerable to the next earth system crisis because we never really did anything about its root, systemic causes – because we were myopically obsessed with the surface symptoms: ‘Other’ people, threatening to take ‘our’ stuff.

We’ve spent the last decade bogged down in fighting the fires of identity politics and culture wars, while the real issues have only worsened.

The irony here is that this doesn’t prove one way or another that the nationalist political turn is inherently bad or wrong: but simply that it is ultimately irrelevant to what’s really going on behind the scenes.

The changes to people’s lives, and the emotions and hardships occurring as a result are happening due to wider, tectonic shifts in the global system that we ignore at our peril: because if we gravitate to a politics that sees and responds only to symptoms, we cannot respond to and transform the underlying systems.

The end result of doing so is a worst of all worlds scenario: we end up trapped in a vicious cycle of diminishing returns – an amplifying feedback loop between earth system disruption and human system destabilisation that drives a protracted process of societal decline.

And this is why, by the end of 2021, a somewhat familiar sequence of energy, climate, food and economic crises once more began to rear its ugly head. Gas price spikes in Europe. Electricity shortages and property debt in China. Government debt in the US. Global wheat shortages due to production shortfalls in Canada, Russia, France and elsewhere.

In 2017, I’d warned that the world needed to “brace for the next oil, food and financial crash”, coming in the years shortly after 2018. Three years later, the processes I had described had become visible.

The civilisational-scale amplifying feedback loop between earth system destabilisation and human system disruption had not gone away, but was continuing in motion through that decade – largely undetected by incumbent political and economic institutions. It was only a matter of time before the unresolved contradictions and vulnerabilities in the global system re-erupted.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, it dramatically accelerated these processes, creating a geopolitical and economic climate that weakened many of the institutional safety measures in place to respond to crisis.

The complex interconnections of these crises in multiple systems across time and space suggests that they are facets and episodes of a single, global systemic crisis.

The accelerating cultural and ideological polarisation we’ve witnessed in recent years is directly related to the widening ecological polarisation between the global human system and the natural world: in other words, our increasing ecological distance from the planet is deepening the rift between and within human societies.

These are not two different things. They are part of the same process in which the global system is rapidly moving out of its equilibrium, which peaked toward the end of the twentieth century, into a new phase of instability and decline.

But as we'll see in my next post, while all this signals the rapidly approaching demise of the current life-cycle of civilisation, it simultaneously heralds the dawn of a new life-cycle that contains the seeds of a new form of sustainable superabundance within planetary boundaries.

If you appreciated this piece, you can keep this free newsletter alive and thriving by joining our community as a Supporter for the price of a cup of coffee a month.

Already have an account? Log In