A new scientific study led by the China University of Petroleum in Beijing, funded by the Chinese government, concludes that China is about to experience a peak in its total oil production as early as next year.

Without finding an alternative source of “new abundant energy resources”, the study warns, the 2018 peak in China’s combined conventional and unconventional oil will undermine continuing economic growth and “challenge the sustainable development of Chinese society.”

This also has major implications for the prospect of a 2018 oil squeeze — as China scales its domestic oil peak, rising demand will impact world oil markets in a way most forecasters aren’t anticipating, contributing to a potential supply squeeze. That could happen in 2018 proper, or in the early years that follow.

There are various scenarios that follow from here — China could: shift to reducing its massive demand for energy, a tall order in itself given population growth projections and rising consumption; accelerate a renewable energy transition; or militarise the South China Sea for more deepwater oil and gas.

Right now, China appears to be incoherently pursuing all three strategies, with varying rates of success. But one thing is clear — China’s decisions on how it addresses its coming post-peak future will impact regional and global political and energy security for the foreseeable future.

Fossil fuelled-growth

The study was published on 19 September by Springer’s peer-reviewed Petroleum Science journal, which is supported by China’s three major oil corporations, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China Petroleum Corporation (Sinopec), and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC).

Since 1978, China has experienced an average annual economic growth rate of 9.8%, and is now the world’s second largest economy after the United States.

The new study points out, however, that this economic growth has been enabled by “high energy consumption.”

In the same period of meteoric economic growth, China’s total energy consumption has grown on average by 5.8% annually, mostly from fossil fuels. In 2014, oil, gas and coal accounted for fully 90% of China’s total energy consumption, with the remainder supplied from renewable energy sources.

After 2018, however, China’s oil production is predicted to begin declining, and the widening supply-demand gap could endanger both China’s energy security and continued economic growth.

The lead author of the study is Professor Jianliang Wang an energy systems expert from the China University of Petroleum’s (CUP) School of Business Administration, along with co-authors Jiang-Xuan Feng and Lian-Yong Feng of the CUP; as well as Jiang-Xuan Feng of the University of Bedfordshire Business School and Hui Qu of the CNPC.

Multiple forecasts

The study, which says its aim is “to help policymakers better understand the future long-term supply of China’s fossil fuel resources”, conducts a thorough review of the scientific literature forecasting China’s oil, gas and coal production.

There are considerable differences in previous forecasts for a peak of conventional oil production, ranging from 2002 to 2037.

One of the main causes for such different forecasts, the authors find, is a failure to distinguish properly between conventional and unconventional resources.

According to a paper last July in Frontiers of Energy co-authored by Sir David King, the UK government’s former chief science advisor, conventional oil is relatively cheap, but on a global scale, production stopped rising around 2005. To meet demand, the shortfall is made up from unconventional oil resources, which despite existing in abundance, are “more costly to produce, provide less net energy and cause more GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions.”

Often Chinese authorities carry out resource assessments which do not adequately account for the economic costs of production, thus overestimating the extent to which these resources might be commercially recoverable.

An oil reserve is said to ‘peak’ when it reaches maximum production at a point when about half the reserve is depleted. After this it becomes geophysically more difficult and economically more costly to extract from the reserve, leading production to gradually decline.

The study does not argue that peak oil means China is running out of fossil fuels — rather as conventional fossil fuels decline, there is an accelerating shift to more expensive unconventional fuels. While these might exist in abundance, the economic costs of exploitation are far higher, leaving some economically unrecoverable.

The end of China’s oil boom

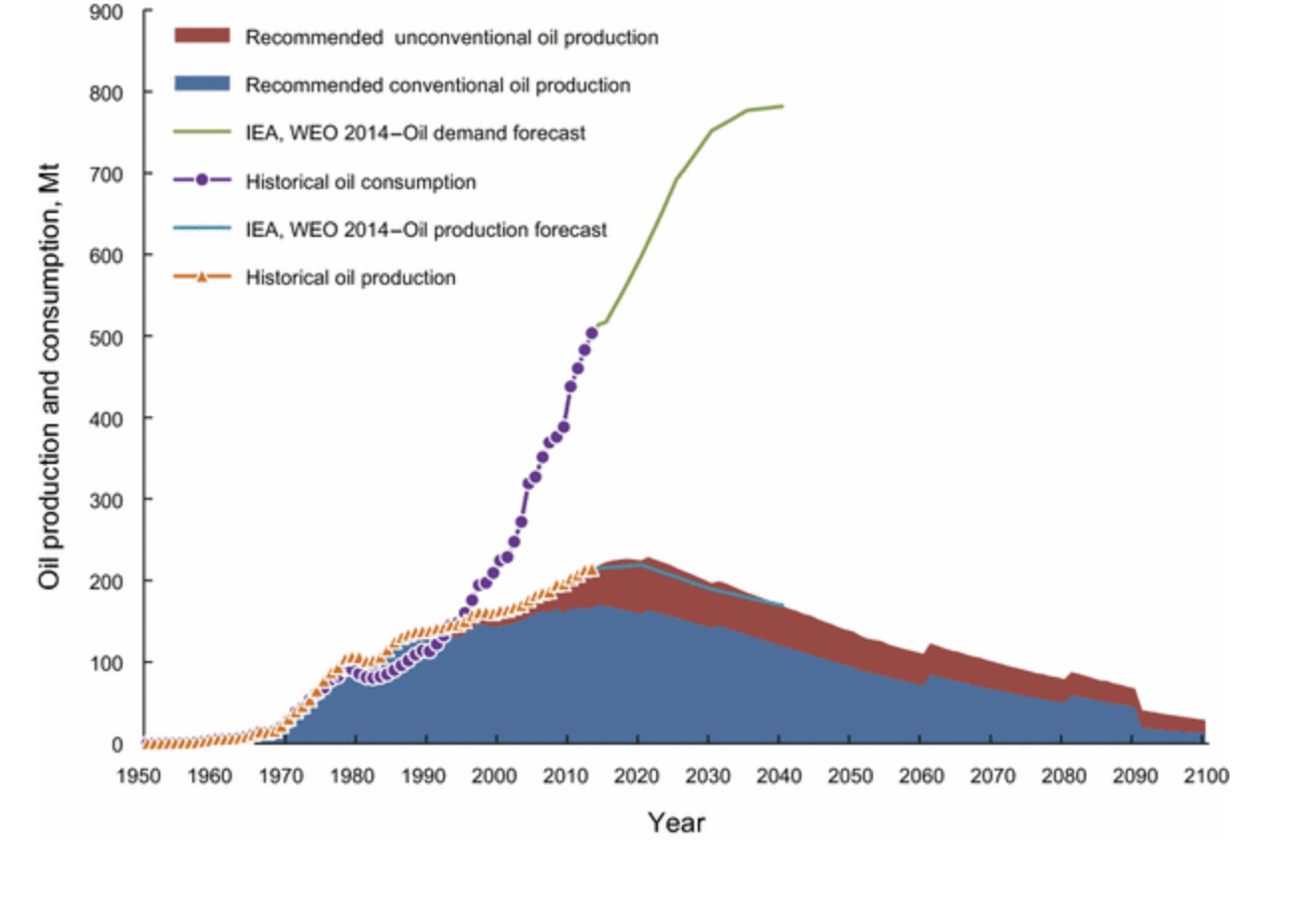

The study’s core finding is that China is about to become a post-peak nation. China’s conventional oil production most likely already peaked in 2014, and the country’s unconventional oil production is likely to peak in 2021.

Assessing China’s total conventional and unconventional oil production together puts its overall ‘peak oil’ date at 2018.

The challenge is that China is simultaneously forecast to experience rapidly increasing oil demand, which would have to come from oil imports — dramatically impacting world oil markets.

From now to 2040, the gap between domestic demand and domestic oil production will increase by 2.7% on average every year. Therefore, the authors conclude that:

“… oil supply security will remain a serious concern for China. Unless demand for oil falls dramatically, there is no other way to meet this supply gap except by oil imports. In such case, it can be expected that the international oil market will be affected significantly by China’s oil import trend.”

Gas

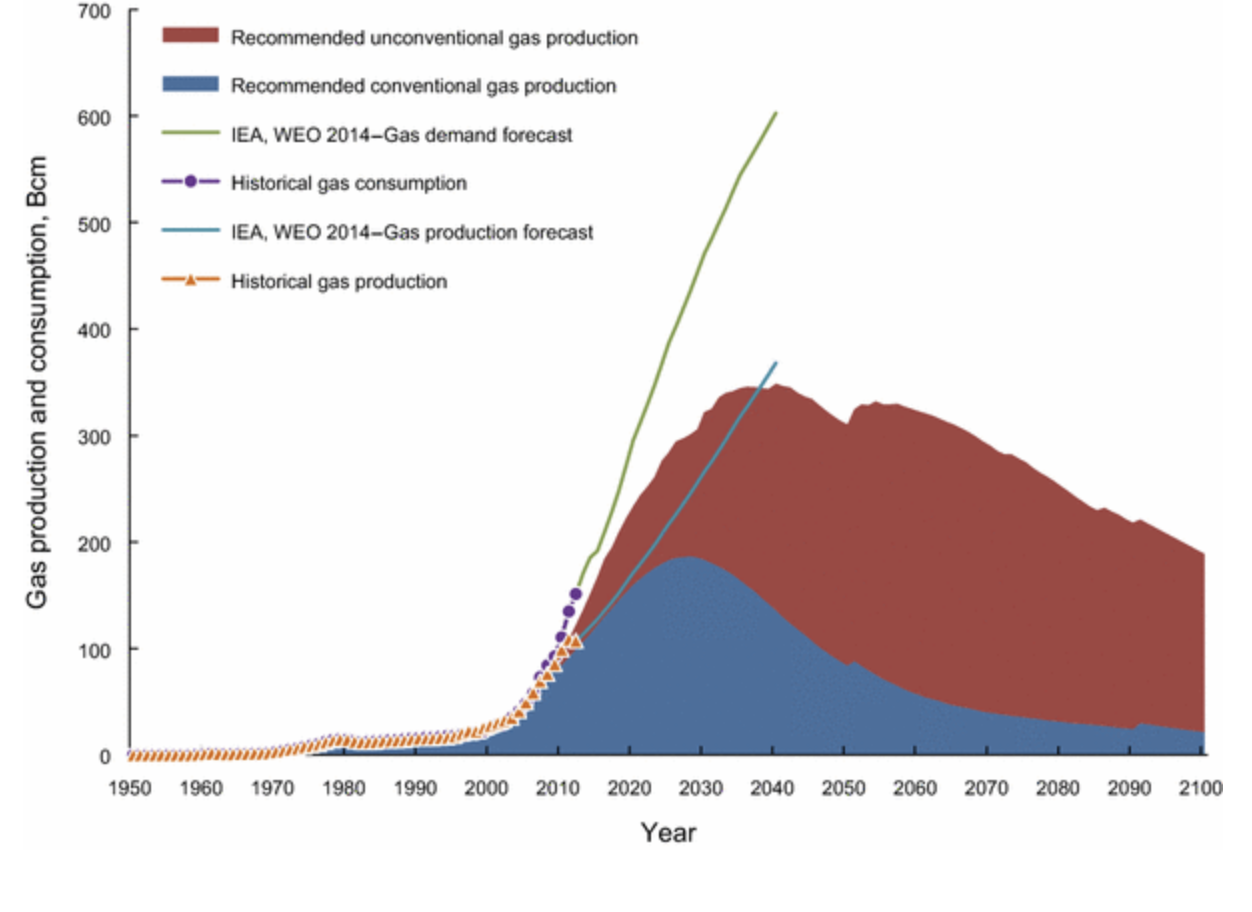

The paper also arrives at new forecasts of China’s gas and coal production. China’s total gas production is likely to peak around 2040, with unconventional gas production surpassing conventional gas around 2034.

Even this scenario could be an overestimate as actual gas production will likely be constrained by “water issues [which] may be the most significant constraining factor for China shale’s gas development.”

China suffers from “high” average exposure to water stress over its shale oil and gas area, the study observes.

Yet China’s gas demand is expected to increase so rapidly, that even “impressive” production increases from unconventional gas resources will not be sufficient to meet demand.

By 2040, gas demand is projected at 600 billion cubic meters (Bcm) per year, nearly double China’s expected total gas production that year at 350 Bcm/year. From there, the supply-demand gap for gas will continue to increase rapidly as domestic production declines.

Climate change?

The impact of water scarcity would not just affect China’s gas production. Other studies set out how it will likely impact on China’s food production.

Projections show that global warming along with land conversion and water scarcity could reduce Chinese food production substantially in coming decades.

Last year, a major study published by the Bulletin of the World Health Organization found that by the 2040s, climate change could reduce China’s per-capita cereal production by 18 percent, compared with 2000 levels.

Out to 2030–2050, loss of cropland resulting from further urbanization and soil degradation could lead to a 13–18 percent overall decrease in China’s food production capacity — compared with that recorded in 2005.

These declines could result in “continued or recurring food shortages” posing a “substantial threat to overall community health and well-being, social stability and human nutrition.”

Coal

Finally, the study takes aim at the government’s exuberance on domestic coal reserves. Coal currently accounts for some 66% of China’s total energy consumption.

China’s coal reserves are believed to be so huge that there is no risk of shortages. The study argues instead that such estimates have little meaning, as it is not clear how much can be produced commercially “under existing economic and political conditions with existing technology.”

Far from China’s coal resources supplying abundant energy for the foreseeable future, the new paper forecasts that China’s domestic coal production is due to peak imminently — around 2020.

This could change depending on domestic demand, as China is spearheading efforts to curb coal consumption.

“The production of coal may peak soon if the demand keeps increasing,” lead author Professor Jianliang Wang told me. “Thanks to the declining coal demand since 2014, China may not see a supply peak of coal if the demand keeps declining in the future.”

Economic impacts of net energy decline

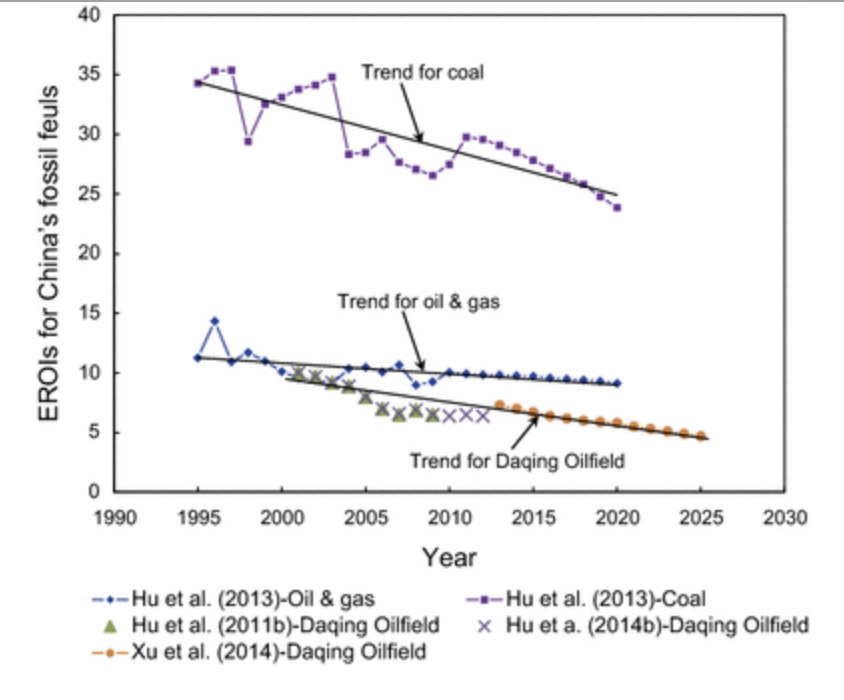

Perhaps the study’s most salient implications are set out in relation to the concept of Energy Return on Investment (EROI), which measures the quality of a resource by calculating the amount of energy needed to extract energy out.

This calculation allows scientists to come to an assessment of a society’s ‘net energy’, and thus how much ‘surplus’ energy is available for investment in economic services outside of the energy system — such as manufacturing, health, food, and so on.

Earlier in the twentieth century, fossil fuel resources were of much higher quality, meaning that very little energy input was required to extract these resources. Their EROI values were at various times higher than 30 and sometimes up to 100 and over.

But the global picture has now dramatically changed “due to the rapid depletion of high-quality fossil fuels after about the year 2000”, which has reduced “the EROI, and hence the amount of energy surplus of fossil fuels to society.”

That’s the global picture, which goes some way toward explaining the inability of the global economy to escape consistently slow-growth.

Within China, available data demonstrates unequivocally that the EROI of fossil fuels exhibits “a declining trend mainly due to the depletion of shallow-buried coal resources and to the move away from conventional oil and gas resources.”

Whereas in the 1990s, the EROI of China’s coal was at around 35, this had declined to about 29 by 2012. It is forecast to drop to 25 and below in coming years.

Similarly, the EROI of China’s oil and gas had reached a high of around 14 in the late 1990s, declining to 9.9 by 2012. It too is predicted to plateau slowly downwards in coming decades.

China’s largest field, the Daqing oil field, provides a clear case study of this process. Just to maintain existing production levels and to reduce the decline rate, China has had to use advanced enhanced oil recovery techniques known for their “high cost and environmental impact”, leading to a lower net energy yield.

This has led Daqing’s EROI to drop as low as 6.4 in 2012.

China’s debt bubble

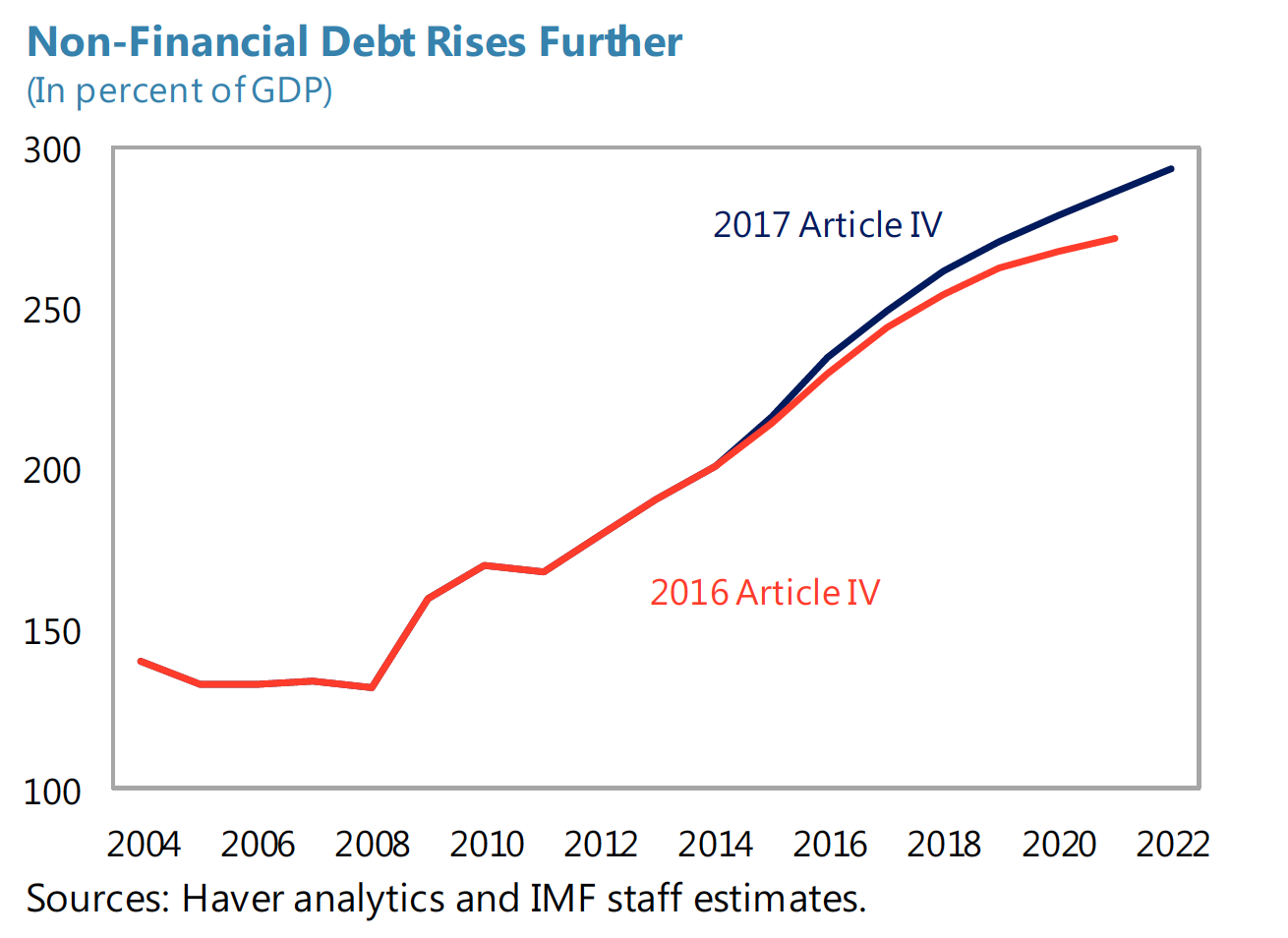

The risk of China’s economic growth is compounded by the fact that it has been fuelled not just by high energy consumption premised on the availability of high-EROI fossil fuels, but also by the meteoric rise in non-financial debt, which includes household, corporate and government debt.

This debt was already 242 percent of GDP in 2016, and according to the IMF will rise to 300 percent by 2022. Viewed in isolation, the unsustainability of this debt-bubble “raises concerns for a possible sharp decline in growth in the medium term”, the IMF found in a report this August.

Risks

Funding for the Petroleum Science study came from a cross-section of Chinese state-backed institutions, including the National Natural Science Foundation, the National Social Science Foundation, the Chinese Ministry of Education’s Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation, and the China University of Petroleum, itself sponsored by the Ministry of Education.

I asked Professor Wang whether this indicated that Chinese policymakers were beginning to take seriously the risk of peak oil.

“Many experts, including those from the government, have already known about our papers and the peak oil issues,” said Wang, explaining that their research group were the first to have introduced the concept of peak oil to China. “The Chinese government has taken measures for years to deal with the problem that China’s domestic oil and gas production can’t meet its demand.”

But he added that while some official agencies supported the basic research, senior Chinese policymakers did not necessarily understand the problem.

Although a significant number of Chinese energy experts agree that “peak oil in China is real and may come soon, they don’t think peak oil in the world is real,” said Wang:

“Therefore, if China can import enough oil with reasonable cost, the impacts on the economy is not considered the key issue by the government. What they care about is the import cost, the world oil price. If the price is too high, this will affect the Chinese economy significantly.”

The study encapsulates this risk succinctly. The authors warn that:

“… supply constraints of oil and gas resources are likely to have very serious impacts on China’s oil and gas security. The gap between domestic production and demand of oil and gas is forecast to increase rapidly. In addition, coal supply constraints show that that a high coal demand scenario is unlikely to be met from purely domestic production.”

These concerns are compounded in the context of China’s mounting debt-bubble, and the intensifying impacts of climate change on China’s water and food availability, which in turn would lead to an escalating dependence on imports of fossil fuels and food — amplifying the total costs on the economy.

Global oil crunch?

All these risks would be compounded if global oil markets experience a supply squeeze of some kind. According to Wang, a peak in total global oil production is likely to arrive sooner rather than later:

“Our group thinks the global oil peak may arrive much early than most people think. So if it happens, the import quantities and import cost will be the big issues that China must consider.”

Last year, INSURGE exclusively published in full a confidential HSBC report concluding that 81% of the world’s total liquids production is in decline, and that this could lead to an oil supply squeeze in 2018.

That view has been partly corroborated by Ed Morse, head of global commodities at Citigroup, who recently said that OPEC producers are for the most part already at maximum capacity, largely due to a lack of investment in exploration and development.

The HSBC report, however, went further than this, concluding that while economic factors are a major issue, most OPEC producers are now facing geophysical constraints which they are unlikely to be able to surpass.

Not everyone agrees with this, with some observers pointing out that even if a supply squeeze kicks in, the price hike could incentivize US shale producers to come online in a matter of days.

Yet either way, the overall picture is that as China’s highest quality fossil fuels are depleted, it will not be able to easily avoid growing pressure from rising energy costs.

China’s rapidly rising dependence on fossil fuel imports further suggests that after 2018, world oil markets will be increasingly strained by the country’s escalating demand. This could well be another potential major driver of a global oil squeeze in or after 2018, in a way that most mainstream forecasts have overlooked.

Highlighting the “steady declining trend” in the EROI ratios of coal, oil and gas, the study notes that this is “generally consistent with the approaching of peaks of physical production of the fossil fuels”.

A decline trend in EROI means that more and more energy inputs are needed to produce the same amount of energy output:

“Such a situation will be unsustainable for Chinese society if China cannot find new and abundant energy sources with high EROI values, or find some way to support one and one half billion people at a dignified standard of living by much less energy-intensive means.”

War for oil?

In response to this looming challenge, China could buckle down on business-as-usual, seeking to consolidate access to new oil and gas sources as part of a wider ‘oil security’ strategy.

This could see China adopt a much more aggressive approach to untapped oil and gas resources in the South China Sea, where Vietnam, Indonesia, Malasyia and the Philippines, alongside China, have contested claims to different offshore oil and gas fields.

Meanwhile, ExxonMobil, whose former CEO Rex Tillerson is now Secretary of State under President Donald Trump, has systematically forged oil deals with all these countries. This implicates the firm — and potentially the US government — in a strategy of encroachment to access South China Sea’s fossil fuel resources.

All this heightens the risk of conflicts in the South China Sea related to energy resource claims, not only between China and local Asian powers, but potentially between China and the US.

Toward a renewable-powered regional super-grid?

China could, of course, adopt an alternative strategy focused on deliberately reducing fossil fuel consumption. China’s current target aims to transition 20% of its energy supply to renewables by 2030.

The projected demand data put forward in the Petroleum Science study suggests, though, that this would still not be sufficient to meet the projected fossil fuel supply gap.

China is also working on a timeline to phase out oil-powered vehicles. For such an initiative to work, China may have to move even faster than it already is.

The study authors suggest that one option is for China to explore “much less energy-intensive means” to support its population, suggesting a concerted shift to lifestyles based on lower consumption.

According to Christian Breyer, Professor of Solar Economy at Lappeenranta University of Technology (LUT), Finland, a rapid Chinese transition to renewables remains feasible and “would allow a high domestic energy supply.”

In 2016, Breyer and his colleague at LUT, Dmitrii Bogdanov, released a peer-reviewed study published in the Energy Conversion and Management journal, showcasing the findings of a detailed model simulation testing the feasibility of a 100% renewable energy system in Northeast Asia.

The model showed that a regional ‘super-grid’ interconnecting Mongolia, Japan, South and North Korea, China and Tibet could provide a secure, reliable energy supply from renewable sources, meeting projected demand-levels out to 2030. And it could do so at significantly lower cost than either nuclear power, or fossil fuel-based carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies.

Breyer and Bogdanov’s model demonstrates that a 100% renewable energy system would be far more viable if countries in the region work together to share and distribute their available resources across an integrated trans-regional smart electricity grid.

But, Professor Breyer told me, China’s mix of solar, wind and hydroelectric sources is excellent, and China would not need such a regional grid to succeed: “China can do that alone, without any doubt.”

He added, though, that “very high shares of renewables” — higher perhaps than China is currently aiming for — “are mandatory… for reasons of fossil fuel availability, energy economics, energy security constraints, military considerations, societal constraints, environmental impacts and health issues. The only question is how fast the transition can be done.”

Given the new study, this transition may well be a matter of survival — not just for China’s future prosperity, but for regional and international security.