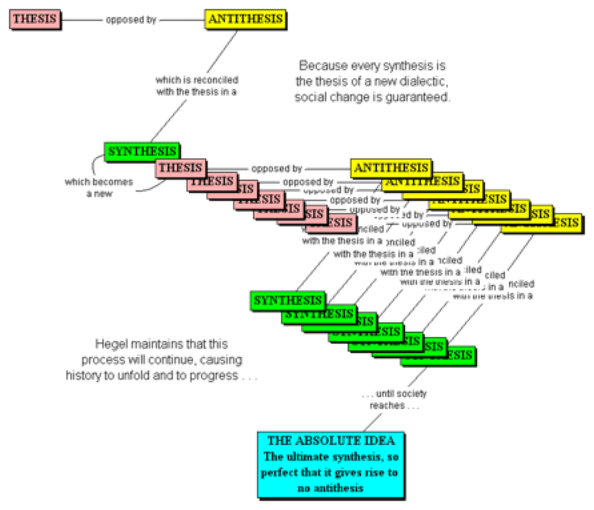

You may be familiar with the Hegelian Dialectic.

In a nutshell, Marx, Engel, Hegel and others helped advance a way of understanding the world that is predicated on this notion of problem, reaction, solution.

One example is ‘terrorism’, which plays on the fears of people who carry different religious and sociocultural beliefs, to the extent that they often refuse to look at the source of the problem itself. What manifests is a kind of panic and apathy in the public sphere that drives policy maneuvering which perpetuates more of the same problem.

The clinical construct for this is reflected in the components of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. The construct is based on opposition, or what we have come to know as resistance.

The implication, or the grand (mis)assumption, is that society somehow reaches a point of dialectical sophistication, such that social change is guaranteed. As Hegel maintained, the process evolves, creating ‘ultimate synthesis’, to which ideas are perfected, resulting in utopian, or dystopian, versions of reality, or the future.

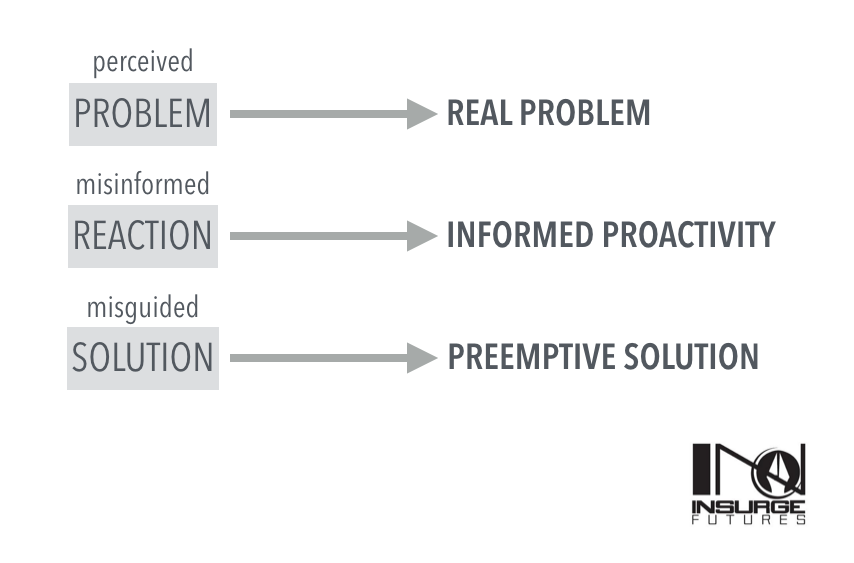

The fundamental challenge with this, as we’ll explore in cursory steps here, is that the problems are mostly perceived, the reactions are predominantly misinformed, and the solutions are often misdirected.

Neoliberalism has promulgated the idea, or the illusion, that institutional vehicles such as philanthropy and impact investing are doing their parts to solve the planet’s greatest societal and environmental issues, when in reality, they are doing just the opposite.

What this really means is that a system has been cleverly designed to seduce people into thinking that their acts of ‘resistance’ are in fact doing good in the world.

It is no great mystery then as to how governments continue to engage in warfare, how institutions mercilessly extract resources from local economies, and how, as a society, we continue to experience racial, cultural and political divides, and as a result, we often endure disenfranchised personal and professional relationships.

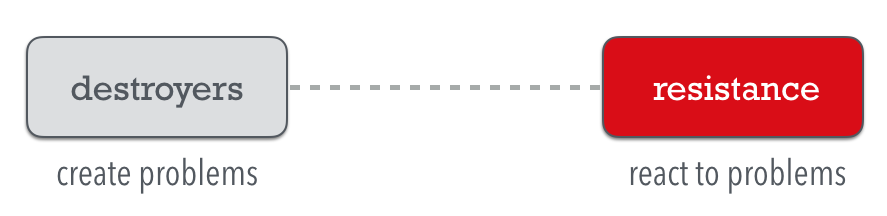

From a strategic perspective, the class of special interests that continues to destroy the planet on all sociocultural, socioeconomic and sociopolitical levels uses resistance as an integral part of its plan to continue to dominate and oppress the masses.

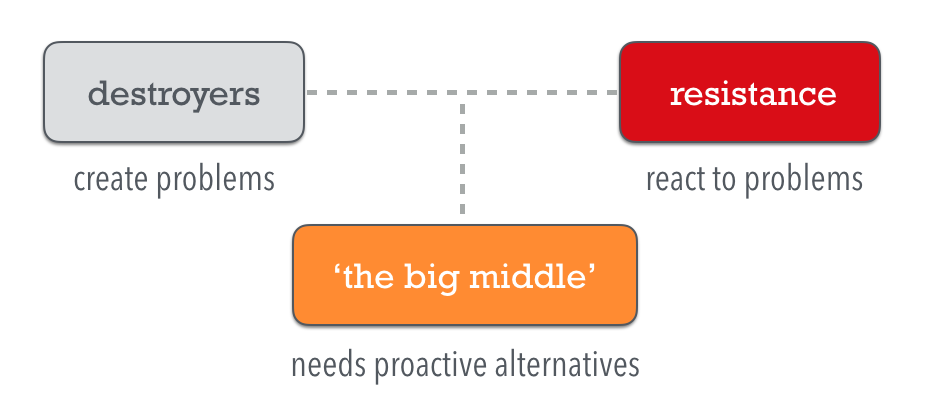

That said, we can break this down into a much simpler construct, based on the duality that already exists. Imagine two main groups — ‘the destroyers’ and ‘the resistance’. The former creates problems, and the latter reacts to them.

What’s really happening is that liberal-progressive movements are playing directly into the hands of a machine — a machine that continues to profit at any cost to the people of the world, and the planet we all inhabit. All the while, the action that needs to happen in ‘the big middle’ is largely being ignored.

Keep in mind that both sides of the machine — the ‘left’ and the ‘right’ — are responsible for the ‘controlled chaos’ that ensues in the current system. Sure, there are green parties and independent groups who advocate for variations of a system that is more just, more equitable, and in some senses more functional, yet relatively little is being done to create change that is transformative, let alone sustainable.

So the point is this: If we are trapped in thinking that our purported solutions can only come from a system that is supported by the very elements that cause mayhem in the world, then we, as ‘changemakers’, are stuck from the onset.

Welcome to the trap that has enslaved western civilization.

Taking Back Reason & The Anomalies Overlooked by Common Sense

As a mental exercise, imagine something for a moment.

If you can, quiet your mind, mute your preexisting beliefs, and try to envision a world that you desire. A place you, your family, your friends and your colleagues can enjoy, feel safe in, participate in, and in general, feel good about. Imagine the elements, everything from the food we eat, to our housing, to our educational systems, to our monetary systems, to our ways of finding health and wellness.

What do you see?

It might be difficult to imagine what this world actually looks like, a different world, and how it operates, given that our notions of what is possible are blighted by what we think we already know.

Thinking or intellectualizing concepts plays a big role in the ways we become separated from the realities that occur ‘on the ground’. It is a determining factor in the cognitive dissonance and cognitive distance we experience as we try to make sense of the world, or the ways we hope it will somehow get better.

Most of us of have deeply neurophysiological reactions to information itself; it is one thing to embrace a concept, it’s another to apply it in the real world and observe how our own assumptions can be ruled out by what we see or experience.

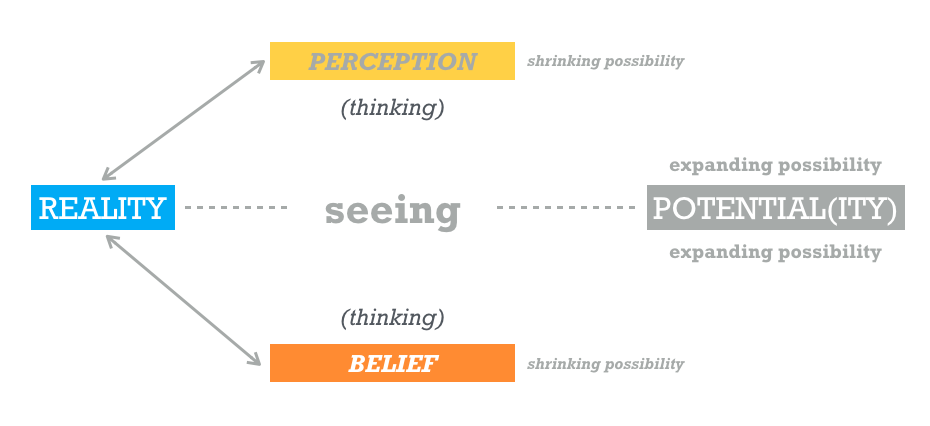

Beliefs and perceptions constrict our capabilities to ‘think outside the box’ — that is precisely why it is much more convenient to adopt ideologies and accept them as truth. However, when we test our assumptions against reality, then we have an opportunity to see what’s actually in front of us. This expands the field of possibility.

For example, if you were to ask most people how they’ve come to certain conclusions or judgments about socioeconomic realities such as poverty, it is likely that they have never actually visited a prison, been on a native reservation, worked with high-risk youth, or actually witnessed how government or financial systems operate. They might be certain that their beliefs are representative of these realities, but they likely don’t really know, firsthand. They are left to believe whatever it is their preconceptions tell them, and are drawn to media and other forms of information that corroborate what they want to believe.

Common sense carries its own forms of compliance and various levels of confusion. Our institutions teach us to choose sides politically, to utilize one hemisphere of the brain or the other, and perhaps as nefarious, not to question the motives of a side that is chosen.

It is also interesting to observe that in doing so, it is rare that we land upon anomalies in what we consider to be ‘common sense’. Anomalous experiences can be had when we leave our comfort zones. Yet, how often does that really happen?

Even more challenging is to consider that we might engage in activities in which we see certain things, such as economic strife, but we are still bound to what we want to believe. This is where correlations can be conflated with causes.

This leads to reactionary measures, such as welfare programs or carbon offsets or accountability standards, that don’t really move the needle in terms of removing problems at their core. From there, it becomes far easier to build programs and initiatives that perpetuate a distorted view of reality, and in turn, suppressing alternative solutions that would require a massive shift in thinking as well as the capabilities to take actions that really matter.

So how might we find those anomalies overlooked by common sense?

Even better, how can we act upon them?

Negative or Inverse Dialecticism

Eastern Indian mystics, spiritual leaders and philosophers have long maintained a view of dialecticism that called upon observers of reality to ground themselves in various forms of negation in order to get to kernels of truth, mostly by way of circumstance. Negation simply meant that conclusions could be reconsidered or removed altogether when making assessments of reality.

Platonian explorations have showed up in public forms of this kind of discourse, in which members of society would occupy physical spaces (such as public squares) and undergo exercises which would paint realities in a different light. Whether these realities were in fact perceivable to all participants or found to be aligned was not the intention; rather, the goal was to enable people to see distinctions in what they perceived as real, and further, to experience the differences in those perceptions such that they would consider other options for living or for serving the public good.

Western philosophers in the 50s and 60s, such as Theodor Adorno, expanded on negative dialectics, poking holes in the Hegelian approach, and, challenged Popper’s and Heidegger’s positions on post-World War II realities. Many of these explorations influenced modern western notions of enlightenment.

Whether or not one actually subscribes to such an inversion is relative. Our forms of communication in culture writ large have centered on Cartesian approaches to understanding the world, and of course, reflect the predominance of Hegelian rationalism. This rationalism is not only fiercely dualistic, but keeps most of us separated from the capability to be logical outside of what is considered ‘normal’.

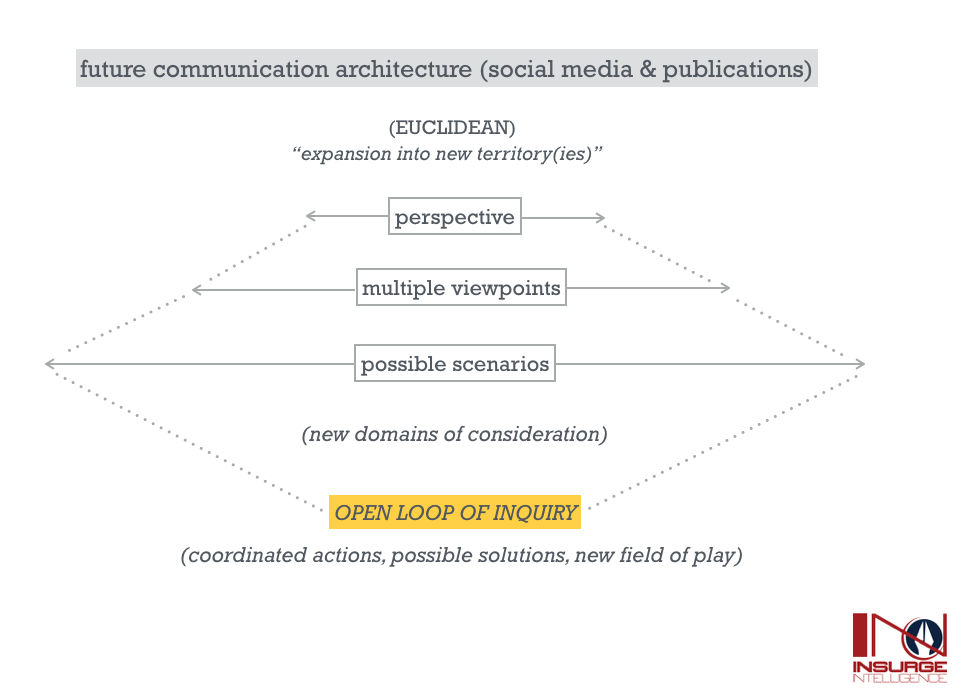

Alas, changing the conversation dynamic, and the rules by which we interact, is a massive initial step forward.

Where this leads us is to a triplet of fundamental Euclidean axioms.

- Change is personal.

- Disruption is internal.

- Nothing is absolute or predetermined other than physical death.

The safety net by which we carry out political, social or environmental discourse is therefore subject to the complacency of the individual. If he or she is committed to not being ‘right’ or being absolute, different outcomes emerge.

This is how will, curiosity and persistence become so vitally important.

Investigative Training & Solutioning

The language of persuasion that permeates our town halls and civic forums has very corrosive effects on our abilities to actually build alternative solutions.

Let me provide a use case that my colleagues and I experience almost on a daily basis.

Nowadays, building things —alternatives — typifies a set of responses from people that is, well, challenging in terms of taking risks and learning from the outcomes as seen or observed in real world contexts.

In our case, we build technology and information solutions to critical issues that range from media systems to education to corporate and government policy, as well as the environment.

Here is a basic framework we use.

What we come across a lot are fixed premises, or wild assumptions, about the world which deliver an unrelenting bias in the prevention of developing sustained solutions. And of course, persuasion is a primary characteristic of this way of interacting.

For example, many groups we’ve interacted with have prefixed notions about money or capitalism. There is a common belief that ‘money is bad’ or ‘capitalism is evil’. Whether these beliefs are true in certain contexts or not isn’t really the point. The point is that, behaviorally, many people are rendered inert in their capacities to explore options simply because they feel that they have to mold behaviors in order to guarantee certain outcomes. Money itself is a behavior that has existed for thousands of years. It all boils down to how it is applied to doing things that can serve the public good.

And, there is a major difference between molding behaviors and enabling various behaviors that are reflective of the true needs in a community, a society, or a cultural group.

So, what often happens are declarative statements that more or less halt the possibility to collaborate, get uncomfortable, and explore territories that are unusual or unknown.

“Prove it to me.”

“Convince me that you’re right and I’m wrong.”

“I don’t believe you’re actually doing these things.”

“That’s not possible.”

“There’s no way you can pull this off.”

“What makes you think you can change anyone or anything.”

“Have you thought this through?”

So on and so forth.

Notice how statements like these externalize problem sets. In other words, there is an absence of will and personal responsibility in the mere task of experimenting with different ways of living and working in the world.

The greatest gift one could have is to accept that no one really knows anything.

This gift does not manifest in a nihilistic sense, but existentially, in learning by doing.

Internalizing Possibility vs. Hopefulness

Many of the same people who act this way are also woefully untrained. The type of training that is required to see the world differently, or to imagine a different world entirely, is one of rigor, consistency, strength and endurance.

As Mari Sandoz once wrote: “I don’t recognize any hopelessness in any struggle with nature. Defeated we are, of course, for death is inevitable, but to the people that seem interesting to me the struggle is a magnificent one in any event.”

One way to look at this is to understand that when we externalize our struggles, we avoid them. Yet, dissonance experienced through struggle is a tool that stretches far beyond cognition. It is rooted the value that experience provides us — negative emotions and all.

And then there’s hope. See if any of these statements ring a bell.

“I hope things change.”

“I hold out for the hope that things will get better.”

“I’m very hopeful that we can find solutions.”

“Hopefully, we can find the strength and fortitude to pull ourselves out of this mess.”

“Hopefully, they will come to their senses.”

So on and so forth. And again, designations such as ‘they’, ‘them’ and ‘it’ tend to externalize problems.

Whether egoistic, collectivist, or a combination of both, these statements also tend to abdicate all responsibility to present and future outcomes.

Experiential Modeling

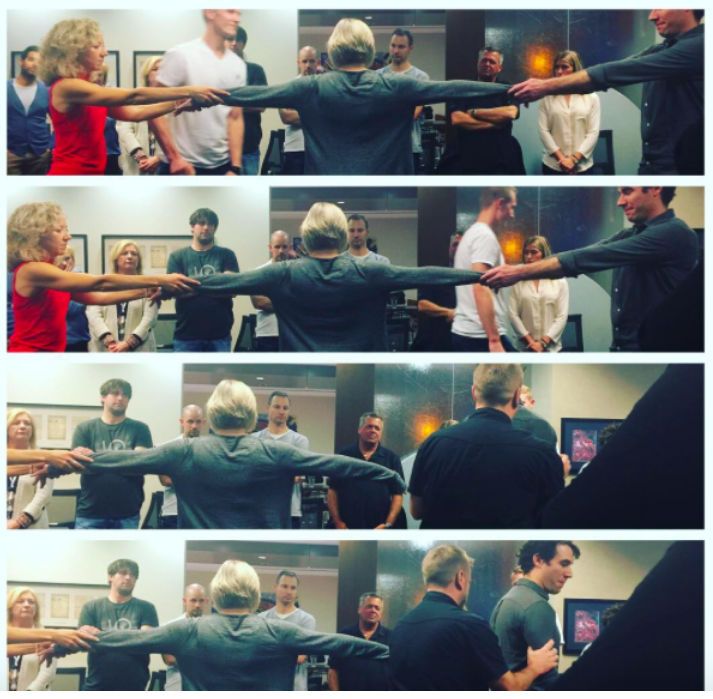

One of the mechanisms we’ve really honed over the years is in designing experiences for people (‘stakeholders’) in physical spaces.

This is important because we all have broken relationships to information which need to be ‘reset’. The information we receive, process and carry forward must be intuited through sensations in the body if we expect different outcomes from our actions.

In more severe contexts, such as in areas of great oppression, experiential design entails a weaving of harsh elements such that people who do not live in these areas or frequent them can begin to develop a sensory relationship to the struggles that local groups or indigenous communities undergo.

Much of this work also requires intense trust-building.

Look into the eyes of a gangster, for example, and he’ll know right away if you’re for real, and if you can be trusted.

A Dynamic Way Forward

With all that has been written here, it really is worth reiterating that no one really knows anything. We can make associations, inferences, and connect dots to the extent that we see things for what they really are.

We can continue to learn and make discoveries by way of experience.

As for you, perhaps someone longing to have a greater impact, a more purposeful presence on the planet, or a simple but concise path towards coming into your own being, there is the opportunity, in this moment, to let go.

Once you do, ask yourself: “What do I see?”

You might be surprised as to what happens from that moment onward.