What’s needed — and what’s on offer — is a truly proactive, economic solution. One that actually creates many more jobs, regenerates resources + capital, and as important, provides leadership for industries full of cowardice as well as confusion.

You may have heard by now about Patagonia’s new effort to sue the Trump administration over national park monuments. As contributing GQ writer Cam Wolf describes it, “…The fact remains: this is still Patagonia’s most masterful branding exercise since its ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ campaign.” It has to make you wonder about the company’s true intentions and its real priorities.

Branding exercises aside, all of the earth’s major environmental problems boil down to a single equivalent: resource regeneration.

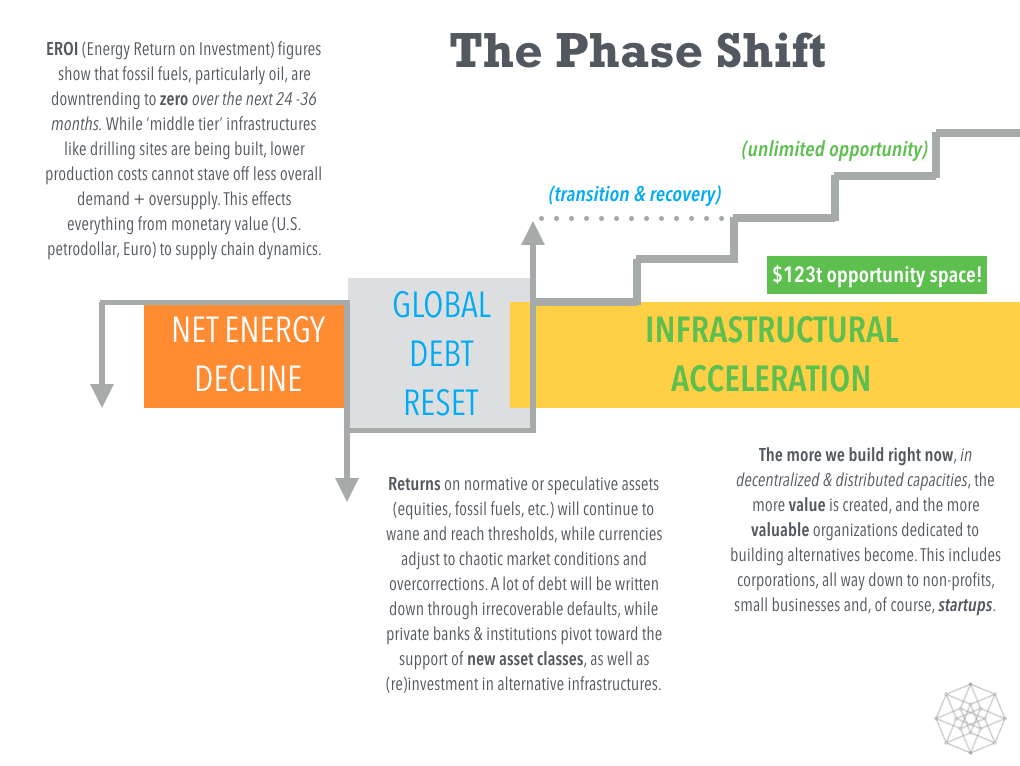

Yes, climate change is very real, and yes, we are seeing cataclysmic effects to include rising ocean levels, and yes, we can also look to sensible measurement constructs such as net energy decline to realize that the opportunity to overturn the damage created from corporate extraction practices is literally right at our fingertips.

So what’s the hold-up? Why isn’t a company like Patagonia leading the charge in creating the ultimate alternative to the way companies operate on this precious planet?

As most of us in business and operations also know, more than 70% of the earth’s known natural resources are controlled, extracted and owned by 147 multinational corporations. And of course, very little if any of those resources are regenerated in any substantial way, even if some of those corporations implement ‘operational appendages’ like biomass conversion and carbon reduction units. By substantial, we mean that supply chains are completely transformed in the way that a company like Mondragon can actually carry stable economic growth by supporting its partners and constituents, and scale its business footprint horizontally by actually doing right by people and planet. In other words, through a real, thriving, open ecosystem.

In vertical industry spaces, and amidst those pesky product ‘ecosystems’, sustainable development has become a veritable joke. While a bunch of bureaucrats shuffle papers around, arguing over the language and use of SDGs (sustainable development goals), claims to ‘100% sustainability’ bubble to the surface in the hopes that CEOs will rally each other past shareholder value and develop policies that supposedly protect local resource and labor pools… Which, of course, they haven’t, and most likely never will.

The Paris Accords are an even more glaring example of how detached we really are from the realities of our global ecological crisis. Under the auspices of ‘climate reform’ and ‘carbon taxation’, a bunch of corporate stakeholders, climate scientists and political cronies sit at the algonquin rountable trying to ‘standardize’ a punishment for corporations who violate the agreement to keep temperatures below X, while taxpayers foot the bill for the so-called indiscretions described as Y. There is very little mention of new manufacturing practices, no real willingness to share resources openly, no real strategy that outlines how these companies and special interests will actually help the economy by making their own adjustments to the damage they have caused themselves. To boot, this model actually disincentivizes smaller, ecologically minded players from entering the market, which is a form of economic suicide.

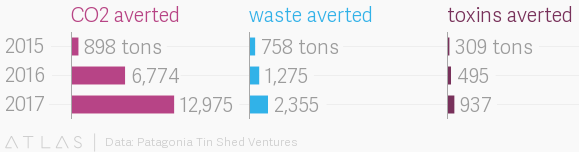

Meanwhile, ‘environmentally led’ companies like Patagonia and REI work on supply chain innovations — or create their own self-sustaining ones — that endeavor to have a ‘negative net impact’ on the planet and labor pools. In Patagonia’s case, its corporate venture arm considers the impact of its investments through metrics of ‘aversion’.

As many pundits have explained in great detail, measurement vehicles such as carbon neutrality and offsetting address the effects of the problem, not the problem itself.

The core problem is current supply chain production and scale, and a lack of viable, scalable alternatives.

As we’ve addressed in other posts, there are $289+t (yes, trillion) earmarked for ‘impact’ investments across funds all over the world, with less than 3% having been allocated for active deployment. What are these funds investing in? Mostly offset-type plays, since many investors have lost their shirts in renewables and biofuels due to poor vetting and operational practices. Not much at all has involved alternative infrastructure or supply chains.

Apart from the fact that deploying just 20% of that $289t would have sweeping economic effects, specifically eradicating national and global debt-to-GDP (we are currently at around 325% of global debt-to-GDP), we, as in the royal we, are blowing it, big time.

The ecological advancements we could make by creating new resources, regenerating them, and developing emerging natural asset classes are the real opportunity. This is the kind of ‘growth’ economists and academics shy away from, even though it’s the best and only way forward.

So let’s look at this logic matrix for just a moment, and really let a certain reality sink in.

On one hand, we are depleting resources at unprecedented scale, and can actually do something about it within a relatively short window of time. On another hand, we are then ‘offsetting’ the damage done by those depleted resources, yet unable to keep up with the damage itself, even though we wouldn’t even need offsets if things like biomass conversion processes were fully integrated into supply chains. Then, to sum it all up, we have more than enough capital to create alternative supply chains, yet aren’t making those investments to have any real impact on the global economy.

Cap-and-trade, impact investing, standardized sustainability metrics… all misguided, and all band-aids being applied to a severely broken leg.

Have we all lost our minds?

According to this recent article in Outside magazine, the big internal tension inside of Patagonia concerns ‘growth’: Founder Yvon Chouinard wanted to limit the company to 5% YTY growth, while current CEO Rose Marcario has boosted the company to annual growth of 14%. The implication is that the company doesn’t need to grow more profitable (it doesn’t), but that it has anyway because of management chops and solid culture.

But this isn’t really the point. Both Chouinard and Marcario are right for complementary reasons.

For Chouinard, equating growth to operational footprint meant that the company would lose its integrity and its products would suffer. For Marcario, the company would develop its innovations around a product and supply chain ecosystem that would preserve integrity AND bolster sales. Which it has.

Yet, both are overlooking an opportunity to completely reinvent growth and scale, and apply it on the ground, regeneratively, right now. This has enormous implications on Patagonia’s organic growth, and scale that will actually rise all boats with the same tide.

In his seminal book “Surviving the Future — Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy”, David Fleming writes about how the complications of largeness lead to four things:

- a loss of elegance, as large infrastructures (the intermediate economy) have to be maintained in order to enable the simple act of living; [ex: rundown towns like Detroit]

- a loss of judgment, as inflexible standardised solutions and ideologies (aka rationalism) destroy the local detail — that living part of the urban ecology on the which the rest depends; [ex: the Paris Accords]

- a loss of presence and direct participation, as people surrender the power to build the institutions they want, which would enable lives that make sense to them. The system as a whole sacrifices the intelligence it needs: it loses its minds; [ex: pervasive lobbying in the form of ‘resistance’]

- and the fourth problem: material waste tends to be lost from the system rather than recycled, as it runs up against a specific difficulty facing large-scale systems. [ex: massive, accelerated resource depletion]

So, growth would be the thing that enables businesses to develop products and services that a market actually needs, while scale would be the way growth is managed across supply chains and industries.

The brilliance of what Fleming has identified leads to the greatest inference imaginable — that the only thing we’re not doing as industries is proactively creating, regenerating and protecting resources at the local level, and doing it not (just) as an ecological imperative, but as a financial necessity that can scale across supply chains and other industries.

Fleming goes on to discuss how this very approach, via small scale, can bolster supply chain development in ways that are commensurate with the capabilities and resource efficiencies of a local ecology. If you look at local ecologies in aggregate, then you have the makings of a healthy economy.

With Patagonia, upon first glance, there appears to be a major caveat regarding what we call managed scale. If you look at its famous organic cotton case study, you see that the company has clearly taken big steps to green its supply chain through a comprehensive ‘fiber-to-fabric’ approach. This approach most definitely has positive affects on partners and constituents, yet there are still major issues with monitoring, management and scale simply because the process removes manufacturing layers rather than actually sharing broader pools of resources and developing more lines of business across supply chains that can regenerate supply, while doing the most good for people and planet.

What we are experiencing is an abject failure of strategy due to a reliance upon an ill-informed ideology, market complacency, and perhaps the most nefarious, a general unwillingness to reframe what the problem + opportunity spaces really are.

Case in point: While Patagonia has successfully developed its own organic cotton supply chain, the fact remains that the vast majority of the world’s cotton is produced by GMO companies.

The company itself has written: “While we were able to achieve two of our goals, the last goal — influencing other clothing companies to also convert to organic cotton — has been mostly a failure. Early on, there were a couple of companies that were inspired by our lead, but few have remained consistent in using organic cotton and the adoption we were hoping for has yet to come. When we first launched our organic cotton line in 1996, organic cotton was less than 1% of all cotton grown and it still is today. This compares with genetically modified cotton that was also less than 1% and is now close to 90% in the U.S. and higher in other countries.”

This confirms our entire position: That unless a company like Patagonia can rise all boats with the same tide, at the end of the day, all of the well intentioned efforts will add up to little more than a massive historical failure. Of which companies like Patagonia must take full responsibility — right away — if they are to do what the world today requires of them.

Alas, there is a silver lining in all of this.

An Unlikely Savior: Privatization

To be really clear, Patagonia is sort of an accidental tourist in the game of environmental protection and corporate sustainability. What we mean by this is that the company is wildly successful and has done a lot of good things… Yet, what it isn’t doing has ramifications that are dire for the future of this planet. Ironically, this also means that it is leaving an awful lot of money on the table both for itself and for its supply chain partners, as well as for its startup ventures.

In terms of privatizing emerging market growth, all we need to do is observe how broken civic and government systems are giving steady rise to new capital + resource streams. The difference between now and yesterday comes down to practicality: instead of subsidizing infrastructural efforts through private debt (private equity), private groups are partnering up with real skin the game, matching capabilities and operational footprints in innovative ways. This is also redefining how public-private partnerships are being created.

Let’s drill down in terms of what this all means in terms of regeneration and ecosystems.

Many U.S. towns, cities and even states are in bankruptcy (the most recent is Illinois), or facing serious fiduciary concessions that have drastic effects on the citizenry, not to mention the mindful use of precious resources. This interdependency between concessions and resources shows us that very few if any companies are taking whole systems approaches to how they manufacture, distribute and build markets that can actually sustain themselves.

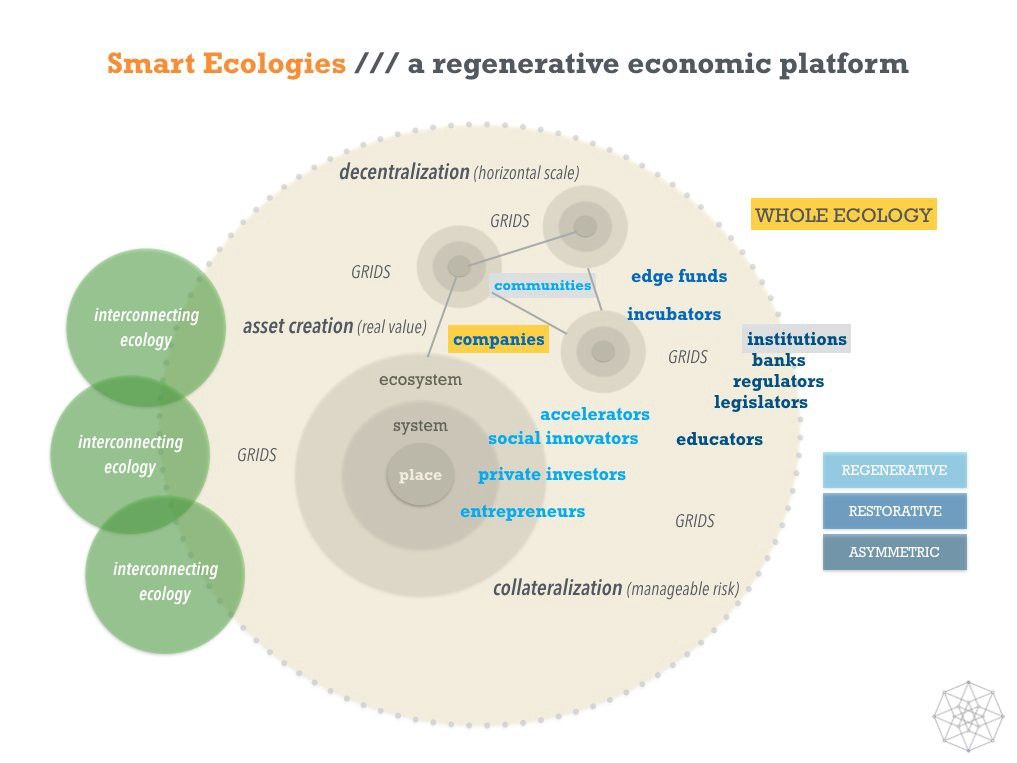

Another way to put it: Companies and their supply chains can’t do business going forward without directly supporting the very markets in which they operate, and, their performance must be tied to what they create in terms of jobs, resources and utilities, not so much what they reduce or avert. This is a very crucial distinction. And, this is the essence of our Smart Ecologies platform.

There are three core axioms for companies in the new paradigm:

I. private resources become public-private subsidies;

II. those resources emerge as new assets + asset classes, then regenerate both their value and their returns on (re)investment;

III. those asset classes create an abundance of new jobs and vocational sets.

Keep in mind that many companies create resources and some have the ability to regenerate them. The challenge lies in the fact that those resources are typically not pooled, shared or redistributed through methods that are discernible and applicable across industries. This is precisely how companies become ecologically relevant AND financially sound.

A New Leadership Edict: The Knock Down Effect

Leadership has been a major issue in terms of how companies can transform their supply chain practices. With shareholder and capital pressures, it’s understandable that CEOs and other upper management folks struggle to implement the necessary changes. However, it’s no excuse, and can’t continue to be one.

In our work with multinationals, family businesses and startups, we’ve seen that economic fatigue is directly tied to how leaders internalize their change practices. In other words, leaders must have real skin in the game and must commit to their own personal disciplines if the intent to step into new operational territories is real and actually possible.

There are three primary lenses leaders must consider as they make decisions for ecological impact:

- their own relationship to tangible + regenerative economic outcomes;

- tying their own performance to those outcomes, and;

- actually being accountable for themselves, their employees and their partners such that growth & scale are interpersonal and ecosystemic.

As we explain in greater detail in Simon and Maria Moraes Robinson’s new book, “Customer Experiences with Soul: A New Era in Design”, it’s an acute association between breaking down old models and seeing market opportunities as civic requirements:

“… the real story is what’s possible when all the normative mental models are broken down and companies can focus on the actual civic requirements of a market — what people and communities really need in terms of natural, intellectual and creative resources. Civic requirements equate to a total market opportunity that is in the trillions. Here in the United States, all you need to do is travel to cities like Detroit, Topeka and East Camden to see both the devastation and the opportunity for yourself.

"Here’s the thing: companies historically have never really thought about how closely aligned their operational footprints and addressable market opportunities are, mostly because they segment populations as ‘consumers’ rather than human beings with socioeconomic attributes and conditions which constantly change. This is the boon in the ‘sustainability’ or regenerative economy equation.”

The even bigger reality is that leaders who can consider a much bigger vision for the planet and society beyond their own career trajectories will make them the stewards of the new paradigm — a business and market opportunity with untold prosperity.

Immediate Next Steps

The slate is wide open in this very moment to commit to the new paradigm. Industry leaders like Patagonia will need to leverage their untapped potential and see a broader, more vibrant and way more stable landscape. Other smaller players will continue to emerge, not only disrupting markets, but in developing their own grassroots ecosystems.

What matters in the immediate term is that we all look at how operational practices, ecosystemic designs, startup investments and adaptive leadership disciplines are wholly integrated to produce the outcomes that can actually make a difference on the planet.

We are committed to this reality. Are you?

Postscript: We spoke with the head of Patagonia’s investment arm, Tin Shed Ventures, and he claimed to be aligned with everything presented in this article. When we presented him with a solution to build a regenerative supply chain ecosystem — one that the company, to date, has not been able to build on its own — he declined the invitation to collaborate. Instead, he was proud to announce that the company had earned a new set of sustainability certifications, even though not much has really changed about its operations nor the effects of the supply chain ecosystem overall.

RELATED ARTICLES & ACTIVE USE CASES:

[INSURGE’s Symposium: Pathways to the Post-Carbon Economy]

[broader perspectives and infrastructural efforts]