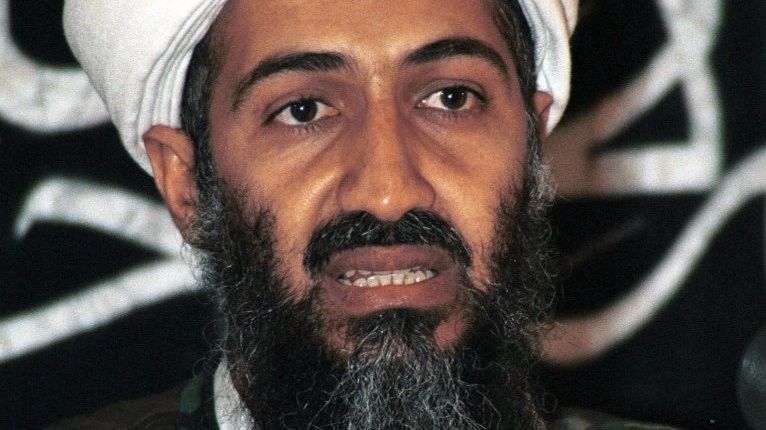

The White House’s story of how US special forces hunted down and assassinated arch terrorist Osama bin Laden in his secret lair in Pakistan is unraveling.

The official narrative of the bin Laden raid is that for over a decade, US intelligence hunted for the terror chief until a surveillance/torture-enabled breakthrough tracked him to a secret compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. On 1st May 2011, US Navy Seals entered the compound and assassinated him in a furious firefight.

The operation demonstrated how far the US military intelligence community had come since the days of 9/11, proving how its disparate agencies had now developed a tremendous capacity to share and process often obscure intelligence data, to guide precision covert counter-terror missions.

After killing bin Laden, the al-Qaeda leader was buried at sea. When the raid was officially announced, Pakistan, a key US ally in the fight against al-Qaeda, was incensed at the US operation on its own soil.

According to veteran reporter Seymour Hersh’s scoop in the London Review of Books, all this is a convenient fairy-tale. Rather, Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) captured and detained bin Laden in 2006 with the support of another US ally, Saudi Arabia.

Bin Laden’s location was brought to the CIA’s attention in August 2010, by a former ISI officer and CIA consultant who wanted to claim the reward money. In 2011, the US staged the military intelligence ‘raid’ on bin Laden’s compound with ISI complicity.

There was no firefight. Bin Laden was torn to pieces quickly and easily under rifle-fire, and his remains were thrown out of a helicopter over the Hindu Kush mountains.

Hersh’s account has been rejected by some on the grounds that he relies on unverifiable anonymous sources. This investigation conducts a systematic review of open sources and key journalistic reports relevant to the events leading up to the bin Laden raid.

While much corroboration for Hersh’s reporting is uncovered, elements of his account and the Official History contradict a wider context of critical revelations disclosed by many other pioneering journalists. When that context is taken into account, a far more disturbing picture emerges.

The geopolitical relationship between the US, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan played a central role in identifying and locating Osama bin Laden far sooner than officially acknowledged — yet nothing was done. The role of a former ISI officer in blowing the whistle on the ISI’s protection of bin Laden in August 2010, brought his concealment out into the open and triggered high-level White House discussions on how to resolve the situation: to kill or not to kill?

Declassified documents, official government reports and intelligence officials confirm that since before 9/11, and continuing for the decade after, the US intelligence community was systematically stymied from apprehending Osama bin Laden due to longstanding relationships with Saudi and Pakistani military intelligence.

Despite specific intelligence available to elements of the US intelligence community on bin Laden’s location in Pakistan, under the protection of US allies, no action was taken to apprehend bin Laden for years. That failure to act coincided with the launch of an anti-Iran US covert operations programme around 2005, pursued in partnership with Saudi Arabia, to finance Islamist Sunni militants including al-Qaeda affiliated groups.

Bin Laden’s assassination in 2011 followed an escalating split within al-Qaeda between the terror chief and his most senior deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri. Contrary to US claims, bin Laden was positively identified and monitored in the months leading up to the raid, with the assistance of Saudi, Pakistani and Afghan intelligence agencies.

The decision to do so coincided with an extraordinary proposal made to al-Qaeda from British intelligence: to accept a renewed ‘covenant of security’, whereby Western forces would withdraw from Afghanistan and give al-Qaeda a free-hand, on condition that they refrain from targeting British interests.

Bin Laden refused the British offer. Four days later he was assassinated.

In the wake of his death, and under the leadership of al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda expanded its operations in many of the countries that had experienced turmoil in the wake of the ‘Arab Spring’ revolutions that year.

Since then — as official Pentagon and other sources confirm — the West’s allies, the Gulf states and Turkey, deliberately sponsored al-Qaeda-affiliated groups in Syria to hijack the revolution and destabilise the Assad regime, a strategy that was covertly supported by the West in 2012, but now openly admitted.

US government officials have scrambled to conceal the facts around the bin Laden raid.

They hope to suppress public recognition that the primary factor in bin Laden’s ability to oversee al-Qaeda until 2011 was US collusion with his state-sponsors, for short-sighted geopolitical purposes.

Corroboration — four years ago

Hersh’s critics, for the most part, have taken issue with his heavy reliance on anonymous sources. As that makes the story supposedly unverifiable, contradictions between Hersh’s narrative and other Known Facts in the ‘war on terror’ Official History mean that Hersh’s narrative must be false.

There is one big problem with this response: Hersh was not the first to break the story.

US national security journalist Dr. Raelynn Hillhouse, a former University of Michigan political scientist and Fulbright scholar who has broken a number of exclusive stories on the privatisation of the US intelligence community, punched holes in the Obama administration’s narrative of the bin Laden raid before Hersh. At that time, her story was blacked out by the US media, but picked up elsewhere such as The Telegraph and New Zealand Herald.

In August 2011, in a series of articles on her national security blog, Dr. Hillhouse cited senior unidentified sources in the US intelligence community who told her that the US government had received notice of bin Laden’s whereabouts from a Pakistani ISI informant, seeking the $25 million State Department reward. Hillhouse’s sources said that “the Saudis were paying off the Pakistani military and intelligence (ISI) to essentially shelter and keep bin Laden under house arrest in Abbottabad.”

What happened then according to Hillhouse’s sources only raises further questions:

“The CIA offered them a deal they couldn’t refuse: they would double what the Saudis were paying them to keep bin Laden if they cooperated with the US. Or they could refuse the deal and live with the consequences: the Saudis would stop paying and there would be the international embarrassment.”

The upshot, Hillhouse reported, is that the ISI and Pakistani military cooperated with the US on the bin Laden raid.

In an interview with The Intercept, Hillhouse confirmed that it seemed clear her sources were different to those who had spoken to Hersh, as they did not consult for US Special Operations Command.

She also said that her own sources had independently confirmed the same facts to her about the disposal of bin Laden’s remains over the Hindu Kush — except that she had decided not to mention this as she couldn’t corroborate it at the time. Hersh’s reporting provided that corroboration.

But the person who first broke this story was neither Hersh, nor Hillhouse. Just days after the raid, former CIA and State Department counter-terrorism official Larry Johnson cited active intelligence sources who told him:

“The US Government learned of bin Laden’s whereabouts last August when a person walked into a US embassy and claimed that Pakistan’s intelligence service (ISI) had bin Laden under control in Abottabad, Pakistan… The claim that we found bin Laden because of a courier and the use of enhanced interrogation is simply a cover story.”

Johnson also confirmed that US intelligence had “learned that key people in Saudi Arabia were sending Pakistan money to keep Osama out of sight and out of trouble.” He also adds some other interesting details, notably that Leon Panetta, then CIA director, ensured that all intelligence leading up to the operation was highly compartmentalised, and fed directly to him.

The charge to assassinate bin Laden was led by Panetta, who wanted to launch the operation as early as February 2011. But it was opposed by Valerie Jarrett, a senior advisor to Obama. The US president “initially sided with Jarrett. The White House spin that Obama had to persuade senior advisors to go after Osama is pure unadulterated bullshit.”

The corroboration of the Hersh account from Johnson and Hillhouse adds weight to its credibility. But other evidence in the public record confirms that it is by far not the whole story: and that the cover-up of events leading to the decision to kill bin Laden occurred precisely to avoid public scrutiny of a wider context of unsavoury geopolitical relationships.

Both the Official History, and the alternate accounts offered by Hersh, Hillhouse and Johnson, agree that the White House did not know of Osama bin Laden’s whereabouts, and that US intelligence was eagerly hunting him down.

But there is already credible evidence in the public record which suggests that while some sections of the US intelligence community were trying to locate bin Laden, other elements of that community had been aware of the likely location of bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, for years, and knew that Pakistani military intelligence was protecting him — but did nothing about it.

2004: Musharraf and ISI

In 2004, three months before the release of the 9/11 Commission Report, executive director of the government-appointed Commission, Philip Zelikow, requested a high-level Pakistani to produce a report that would “fill in the gaps about what was happening behind the scenes in Pakistan in the period immediately preceding the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington.”

The report was perhaps the most extensive piece of research on Pakistan’s connections to terrorism, and was based on interviews across the country with sensitive sources including former and active government officials, senior military officers and ISI personnel.

Although the document arrived too late to be included in the final report, like many other sensitive interviews and materials obtained by the Commission, it was not published and remains classified.

Leaks about the content of this classified addendum to the 9/11 Commission Report showed that it had concluded that senior ISI officers had known in advance about the 9/11 attacks, that Osama bin Laden was being protected by Pakistani military intelligence officials, and that President Pervez Musharraf himself had approved for the terror chief to be treated for renal problems repeatedly at a military hospital near Peshawar.

Zelikow, currently a consultant to the Office of the Secretary of Defence, was a former White House National Security Council staffer in the first Bush administration, and a member of President Bush Jnr.’s 2000–2001 transition team, before joining the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) until 2003. During his tenure, he played the lead role in re-drafting the Bush administration’s new National Security Strategy. After his directorship of the 9/11 Commission, he was appointed Counselor of the State Department for Secretary of State Condaleeza Rice. More recently, under the Obama administration he served once again on the PFIAB from 2011 to 2013.

The existence of this classified report to the 9/11 Commission demonstrates that the US government had received detailed intelligence confirming the protection of bin Laden by senior Pakistani government, military and intelligence officials as early as 2004.

2006: Abbottabad flagged

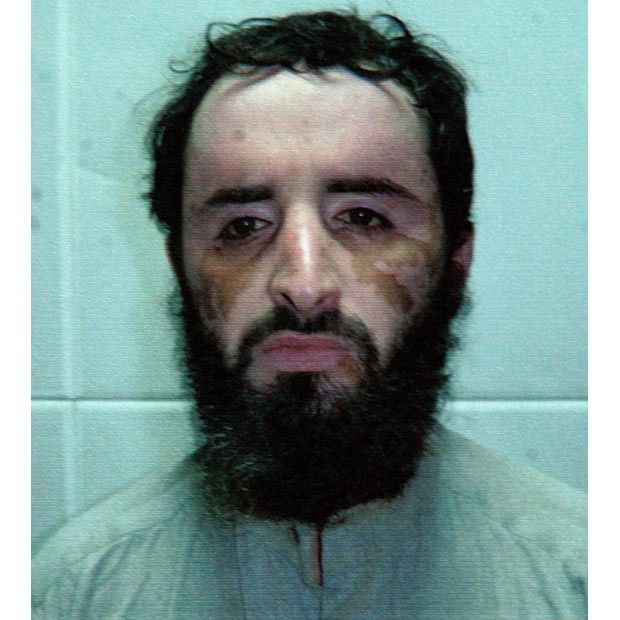

Bin Laden’s specific location in Abbottabad had been flagged up in a secret September 2008 US Department of Defence memorandum from Joint Task Force Guantanamo to the Commander, US Southern Command. The memo contained information obtained from Abu Faraj al-Libi, al-Qaeda’s “operational chief” and third in command.

Al-Libi is described by the document as manager of al-Qaeda operations in Iraq, as well as a “senior commander of operations in Pakistan who maintained communication with senior al-Qaeda leadership including UBM [Osama bin Laden].”

Detained by Pakistani security forces and passed to the CIA in May 2005, the document recorded that he had “provided safe havens for UBL and senior al-Qaeda leader Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri in 2001 and 2003.”

The document goes on to say that in July 2003 — the year that al-Libi provided a safe haven for Osama bin Laden:

“… detainee [al-Libi] received a letter from UBL’s designated courier, Maulawi Abd al-Khaliq Jan… UBL stated detainee would be the official messenger between UBL and others in Pakistan. In mid-2003, detainee moved his family to Abbottabad, PK [Pakistan] and worked between Abbottabad and Peshawar.”

Thereafter, Abu al-Libi continued to be “the main contact between UBL and Islamic extremists operating inside Pakistan,” and was described as “the communications gatekeeper for UBL and al-Zawahiri.”

According to Gareth Porter, citing Mehsud tribal sources in South Waziristan, Pakistan, al-Libi himself had been tasked with finding the best location for bin Laden and his family to reside, and had “suggested Abbottabad.”

The document thus reveals that al-Libi had moved to Abbottabad precisely to carry out his appointment as bin Laden’s official emissary — a major indicator of bin Laden’s likely presence in Abbottabad. He was simultaneously to act as a communications gatekeeper for al-Zawahiri — a major indicator of al-Zawahiri’s likely presence near bin Laden in Abbottabad.

Al-Libi had been passed onto the CIA by Pakistani security forces in late May 2005, during which he provided detailed information on plans by UK-based cells to attack nightclubs and the “subway” network in London, before being moved to Guantanamo the following year.

CIA records show that the torture and interrogation of al-Libi had exhausted the retrieval of information long before his transfer to Guantanamo in September 2006. After more than a month of continually applied ‘enhanced interrogation techniques,’ the decision was eventually made to cease their use as “CIA officers stated that they had no intelligence to demonstrate that Abu Faraj al-Libi continued to withhold information, and because CIA medical officers expressed concern that additional use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques ‘may come with unacceptable medical or psychological risks.’”

So the information filed in the 2008 Pentagon report, which collated the basis for recommending al-Libi’s prosecution, had in fact been extracted by the CIA prior to his move to Guantanamo in September 2006.

Therefore, as early as 2006, the CIA had compelling evidence that bin Laden had planned to operate from Abbottabad since 2003, and was communicating with militants in Peshawar and elsewhere through al-Libi.

That document disproves claims by Hersh’s sources that bin Laden moved to Abbottabad in 2006 as a result of his betrayal by locals who handed him over to the ISI for money — rather, the al-Qaeda chief had begun that move three years earlier of his own accord.

2006: NATO spots bin Laden

Hersh’s account asserts that bin Laden had been detained under “house arrest” at the Abbottabad compound since 2006 by the Pakistani ISI as part of a deal with Saudi Arabia, but that the US was not privy to this arrangement.

Yet in the same year, secret US military intelligence documents confirmed not just one, but regular monthly sightings of bin Laden in Pakistan at al-Qaeda planning meetings. A NATO threat report from the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan — part of the Afghan War logs published by Wikileaks — stated:

“Reportedly a high-level meeting was held in Quetta, Pakistan, where six suicide bombers were given orders for an operation in northern Afghanistan. Two persons have been given targets in Kunduz, two in Mazar-e-Sharif and the last two are said to come to Faryab… These meetings take place once every month, and there are usually about 20 people present. The place for the meeting alternates between Quetta and villages (NFDG) on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan… The top four people in these meetings are Mullah Omar [the Taliban leader], Osama bin Laden, Mullah Dadullah and Mullah [Baradar].”

Although the paucity of reports on bin Laden in the Afghan War logs is testament to the terror chief’s largely successful efforts at discretion, they show that as early as 2006, having surmised bin Laden’s location in or near Abbottabad, US intelligence and its assets on the ground had repeatedly sighted bin Laden.

From 2003 to 2009, as the few other intelligence reports in the logs reveal, bin Laden moved around Pakistan routinely, playing a key role in galvanising and planning terrorist operations. He was certainly not under house arrest.

2007: NSA confirms bin Laden in Pakistan

According to top secret National Security Agency (NSA) documents leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden, US intelligence had confirmed bin Laden’s location in Pakistan in 2007, and been able to track his communication from Pakistan to al-Qaeda operatives in Iraq and Iran:

“SIGINT [signals intelligence] uncovered a message from Usama bin Laden (UBL) intended for al-Qa’ida’s #1 man in Iraq… The message was dated 12 February 2007 and was passed via a communications conduit. The movement of the letter from Pakistan to Iran provided the US intelligence community with unique insights into the communications path used by senior al-Qa’ida leaders in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan to communicate with al-Qa’ida leaders in Iraq and Iran.”

The intelligence report on the bin Laden communication — clearly confirming his residence in Pakistan and homing in on the “communications path used by senior al-Qa’ida leaders” — was circulated to the Vice President, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, and the Attorney General, who gave it “rave reviews.”

2008–2009: bin Laden’s “villa” in Abbottabad

After the May 2011 bin Laden raid, renowned ABC News correspondent Christiane Amanpour revealed that precise intelligence on bin Laden’s location had been available much earlier.

She recalled that during a live interview with Bill Maher in early 2008, she had told her host that a senior US intelligence officer informed her of bin Laden’s location in a villa in Pakistan:

“I just talked to somebody very knowledgeable… This woman who is in American intelligence thinks that he’s in a villa — a nice comfortable villa in Pakistan.”

When Maher joked whether the villa was in Cabo, Amanpour replied that bin Laden was “in Pakistan. Not a cave.”

The detail is worth noting — the source appeared to be aware of bin Laden’s location down to the comfort of his building.

India’s external intelligence service had also provided specific information to its US counterparts on bin Laden’s presence in “a cantonment area” — a military or police quarters — “in a highly urbanised area near Islamabad.” The intelligence also included “definite information that his [bin Laden’s] movement was restricted owing to his illness and that it would have been impossible for him to go to an ordinary hospital. We told the Americans that only in a cantonment area could he be looked after by his ISI or other Pakistani benefactors.”

The US did not show much interest in these revelations, according to a senior Indian security source.

The main “cantonment area” nearest to Islamabad is precisely the Pakistani military garrison city of Abbottabad, which is just 75 miles north of the capital. Bin Laden’s compound was 800 odd yards from the Pakistan Military Academy, the equivalent of America’s West Point.

Even Pakistan’s own government believed that Abbottabad served as an al-Qaeda haven. According to an official statement from the Pakistani Foreign Ministry, the ISI had been monitoring bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad for years, and was providing specific intelligence to the US about the compound since 2009.

Abbottabad generally had been “under sharp focus of intelligence agencies since 2003” due to its role as an al-Qaeda stronghold, according to the Foreign Ministry statement:

“The fact is that this particular location [of bin Laden’s compound] was pointed out by our intelligence quite some time ago to the US intelligence. The intelligence flow indicating some foreigners in the surroundings of Abbottabad continued until mid-April 2011. It is important to highlight that taking advantage of much superior technological assets, CIA exploited the intelligence leads given by us to identify and reach Osama bin Laden.”

Pakistan had purportedly urged the US to identify the occupants of the compound, as the US had “much more sophisticated equipment to evaluate and to assess” what was going on inside.

The CIA and the White House did not deny that this intelligence was shared by Pakistan with its American counterparts.

Other Pakistani ISI sources went further than this official statement in off-the-record interviews with Pakistani Army officer Brigadier General Shaukut Qadir. They told Qadir that they had identified the Abbottabad compound as a likely terrorist base in July 2008, and asked the CIA to conduct surveillance of the building.

In his book, Operation Geronimo (2012), Qadir — who has no ISI affiliation — writes that these ISI sources were unaware of bin Laden’s presence at the compound at the time, but confirmed that the building was being investigated for connections to terrorism. National security journalist Gareth Porter reports:

“Five different junior and mid-level ISI officers told Qadir they understood Pakistan’s Counter Terrorism Wing (CTW) had decided to forward a request to the CIA for surveillance of the Abbottabad compound in July 2008.”

Abbottabad safe-house

Satellite photographs show that bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound was not present in 2001, but appears on images in 2005, confirming it was built that year.

Yet according to the Associated Press, bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad had been “known” to the US intelligence community “for years” — in what sense it was known, AP does not clarify:

“The walls surrounding the property were as high as 18 feet and topped with barbed wire. Intelligence officials had known about the house for years, but they always suspected that bin Laden would be surrounded by heavily armed security guards. Nobody patrolled the compound in Abbottabad.”

According to one ISI official speaking to the BBC: “Just look at the house — it sticks out like a sore thumb from a mile off. You’ve been to Abbottabad — you know how these small towns are. Everybody knows everything about everybody, and secretive people are routinely investigated, especially by the police.”

In October 2010, a senior NATO official “with access to some of the most sensitive information in the NATO alliance” told CNN that both bin Laden and his deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri were believed by the intelligence community “to be hiding close to each other in houses in northwest Pakistan, but are not together.”

The CNN report explained:

“… al Qaeda’s top leadership is believed to be living in relative comfort, protected by locals and some members of the Pakistani intelligence services, the official said.”

This report suggested that NATO intelligence had pinpointed both bin Laden’s and al-Zawahiri’s location to particular “houses” in northwest Pakistan — but, contrary to the Official History, that NATO was fully aware of their protection by ISI officials. This corroborated the CIA intelligence extracted from al-Libi between 2005 and 2006 on the proximity of bin Laden and al-Zawahiri in Abbottabad, under ISI tutelage.

Therefore, the evidence is overwhelming that by 2008, the US intelligence community was in receipt of detailed, specific information from Indian, Afghan and Pakistani intelligence, locating Osama bin Laden in a military cantonment area in Abbottabad — and pinpointing the location of his compound.

Surveillance

If Hersh’s account is correct, this means that despite all this intelligence pinpointing the Abbottabad compound, the CIA waited several years before establishing a safe-house nearby to conduct extensive surveillance on the premises using telephoto lenses, eavesdropping equipment, infrared imaging, and radars — only after walk-in source exposed bin Laden’s concealment in August 2010.

The CIA also, according to the Official History, deployed dozens of high-altitude stealth drones in Pakistani airspace for months before the raid to capture high-resolution video.

In the context of the evidence of mounting intelligence pinpointing bin Laden in the Abbottabad compound, the Official History raises the following question: Why, in the wake of all the intelligence that bin Laden was in Abbottabad, and despite receiving the request from a Pakistani counter-terrorism agency to investigate the Abbottabad compound in July 2008 — as reported by Brig. Gen. Qadir — did the CIA wait until late 2010 to do so?

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the CIA inexplicably sat on intelligence pointing to bin Laden’s presence in the Abbottabad compound for over two years, and perhaps much longer.

When the CIA finally began moving into action, the Official History has it that these efforts were done in such secrecy that even Pakistani intelligence, which was also monitoring the compound, did not know about the CIA surveillance operation (despite having requested it in 2008).

And despite the sophistication of that operation, the Official History has it that the CIA was never able to identify Osama bin Laden. Instead, they managed to catch a glimpse of a man taking regular walks through the compound’s courtyard, who roughly fit bin Laden’s description, and whom intelligence officers dubbed “the pacer.”

Former Canadian Army officer and electronic communications specialist Prof. Sunil Ram, who teaches members of the US Armed Forces at the American Military University in West Virginia, dismissed the idea that such sophisticated surveillance could not have identified bin Laden:

“The public farce around the months of CIA surveillance to determine if it was bin Laden defies logic.”

This is backed-up by Jack Murphy, an eight year US Army Special Operations veteran, in a 2011 article for Sofrep, the news and analysis website run by former US military and special operations officers:

“In reality, Bin Laden was not tracked to the Abbottabad compound by following his courier network. That story was ludicrous when it was first leaked and got even sillier in Bigelow’s movie. Also, the use of stealth aircraft and reports of UAVs conducting electronic jamming operations to obscure the radar signature of the helicopters was also a myth. The truth is that the highest levels of the Pakistani government knew that the [SEAL Team Six’s] Red Squadron assaulters were coming. At least two Pakistani Generals were informed, and this is how Operation Neptune Spear was able to take place so deep into Pakistan without the Pakistani military scrambling fighter jets or troops to the scene.”

Murphy’s confirmation that “at least two Pakistani Generals” had advanced knowledge of the raid, corroborates Hersh’s identification of former Army chief Gen. Ashfaq Kayani and ISI director Gen. Ahmed Shuja Pasha, as the senior Pakistani generals complicit in the raid.

Corroboration for these assertions comes in the form of an ISI source who spoke to Robert Fisk, one of the few journalists who had interviewed bin Laden face-to-face. “I called up one of the [ISI] men I know last night,” Fisk told al-Jazeera, “and put it to him, ‘look, you know, this house was very big, come on, you must have have had some idea.’

“What he said to me was ‘sometimes it’s better to survey people than to attack them.’

“And I think what he meant was that as long as they knew where he [bin Laden] was, it was much better to just watch rather than stage a military operation that may bring about more outrages, terrorism, whatever you like to call it.”

If the ISI had long monitored the compound, and requested the CIA to monitor it too, the idea that they had no idea the CIA was also monitoring it beggars belief.

Indeed, New York Times journalist Carlotta Gall, who has spent over a decade reporting from Afghanistan and Pakistan, cites Pakistani officials who give a completely different picture of bin Laden’s presence at the compound, consistent with the sparse reports already discussed from Wikileaks’ Afghan War logs.

Far from being holed-up to avoid detection, or under house arrest, bin Laden “occasionally traveled to meet aides and fellow militants,” wrote Gall.

One Pakistani security official told her:

“Osama was moving around. You cannot run a movement without contact with people.”

Gall added:

“Bin Laden traveled in plain sight, his convoys always knowingly waved through any security checkpoints.”

She cites a Pakistani Interior Ministry report (conducted therefore by Pakistan’s domestic intelligence agency, Intelligence Bureau), which confirmed in 2009 that bin Laden had met with Qari Saifullah Akhtar, leader of the group Harkat ul-Jihadi al-Islami, the first Pakistan-based jihad network formed during the Afghan war against Soviet occupation. According to the Pakistani intelligence report, the two discussed militant operations against Pakistan.

The meeting, and its monitoring by Pakistani authorities, is significant for several reasons. It shows that Hersh’s narrative that bin Laden was under “house arrest” in Pakistan under the alleged arrangement with the Saudis is incorrect. If that arrangement existed, Pakistani authorities had guaranteed bin Laden’s freedom of movement in the country.

The report also corroborates the sources reviewed above asserting that Pakistan had been closely monitoring the Abbottabad compound for some years. But those sources did not acknowledge the implied kicker of Gall’s piece: the positive identification of Osama bin Laden inside Pakistan by certain government authorities in 2009, and the meticulous surveillance of his movements by Pakistani intelligence.

Fateful triangle: US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan

The Official History claims that the bin Laden raid was fundamentally and solely a US operation.

Hersh’s account claims that events leading up to the raid revealed that bin Laden was under house arrest by the Pakistani ISI, with Saudi financial support.

But the preceding reports indicate that bin Laden was never under house arrest, that his residency in Abbottabad had been confirmed to US intelligence at least three years before the raid, and that his meetings with militants were being routinely tracked by Pakistani intelligence — which was urging the CIA to investigate the Abbottabad compound as of July 2008.

Yet a further extraordinary report discredits the official and Hersh accounts even further. Both Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, who were harbouring bin Laden in the first place, were also conducting extensive surveillance of bin Laden’s movements in the months leading up to the raid, on behalf of the US.

In other words, in early 2011 the US was working directly with the same Saudi and Pakistani governments that had been protecting bin Laden in Abbottabad.

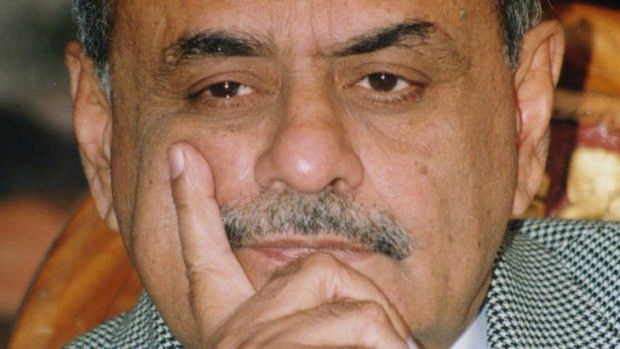

The report was authored two months before the raid by the late Syed Saleem Shahzad, Pakistan bureau chief for the Hong Kong-based Asia Times and the Italian news agency, Adnkronos. Shahzad was described by the New Yorker as being“known for his exposés of the Pakistani military.”

In his Asia Times article, Shahzad reported that the CIA had launched a series of covert operations in the Hindu Kush mountains of Pakistan and Afghanistan after receiving “strong tip-offs that al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden has been criss-crossing the area in the past few weeks for high-profile meetings.” Bin Laden had been tracked to “Kunar and Nuristan for meetings with various militant commanders and al-Qaeda bigwigs.”

US “decision-makers have put a lot of weight on the information on Bin Laden’s movements as it has come from multiple intelligence agencies, in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia.” Intelligence officials now believe they have “top-grade accounts as they come from the inner circles of militant camps.”

Intelligence officials, Shahzad wrote, were “‘stunned’ by the visibility of Bin Laden’s movements, and their frequency, in a matter of a few weeks in the outlawed terrain of Pakistan and Afghanistan.”

He cited “leaks” from the “inner circle” of the militant group, Hizb-e-Islami Afghanistan (HIA), confirming that weeks earlier, bin Laden had met with the group’s leader, “Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the legendary Afghan mujahid… in a militant camp in thick jungle on the fringes of Kunar and Bajaur provinces in Afghanistan.”

During the Cold War, Hekmatyar’s HIA received the largest share of military and economic assistance from Saudi Arabia, supervised by the CIA and delivered through the Pakistani ISI.

After the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan, HIA was among the many insurgent groups, including the Taliban, that targeted NATO troops and Afghan security forces. But in the years preceding the bin Laden raid, this changed as the US sought ways to end the insurgency and stabilise Afghanistan’s Hamid Karzai regime. Saleem Shahzad noted that:

“Hekmatyar’s representatives of the HIA have been in direct active negotiations with the Americans and have also brokered limited ceasefire agreements with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces in Afghanistan.”

Journalist Edward Girardet, in his book Killing the Cranes: A Reporter’s Journey through Three Decades of War in Afghanistan (2011), reports that in 2009, he was told by former HIA supporters in Kunar, eastern Afghanistan, that “Hekmatyar was operating from the Pakistani frontier tribal agencies of Mohmand and Bajaur with the support of the ISI.”

Thus, throughout this period, bin Laden’s movements appear to have been heavily monitored by the ISI, which even knew precise details about bin Laden’s discussions with Hekmatyar. Shahzad refers to “intelligence sources” that were “privy to the meeting in Bajaur,” where the two terror chiefs discussed a future “grand strategy.”

Corroboration for Shahzad’s report of Osama bin Laden being on the move comes from an interview of a senior official of the Taliban faction, the Haqqani network, by BBC reporter, Syed Shoaib Hasan. The Haqqani network member told the BBC that “he met Bin Laden near the town of Chitral two months ago” — that is, two months before the raid.

Shahzad’s report flies in the face of claims that bin Laden could not be identified by CIA surveillance because he never left his compound, or that he was under perpetual house arrest at the behest of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. It also corroborates the other reports showing that bin Laden had significant freedom of movement, albeit under the watchful eye of the ISI, and extensive patronage of ISI-sponsored groups, HIA and the Haqqani network.

But more strikingly, Shahzad’s report shows that elements of Pakistani, Saudi, and Afghan intelligence agencies were all involved in monitoring bin Laden’s movements, and were regularly sharing intelligence on bin Laden with the CIA. Clearly, though, this hitherto unacknowledged joint surveillance operation was highly compartmentalised, and known to only certain specialised units in these agencies.

Given that therefore both the Official History and Hersh’s account omit this revelation, the question must be asked as to how long the US was in fact cooperating with Saudi and Pakistani intelligence to monitor bin Laden as he moved back and forth from his base in Abbottabad?

At the end of May 2011, nearly a month after the bin Laden raid, Shahzad was tortured and murdered.

A Human Rights Watch investigation concluded that Shahzad had been assassinated by the Pakistani ISI. Obama administration officials later revealed that classified intelligence proved the culpability of senior ISI officials in directing the operation.

The fact that the US government had such intelligence on the inner high-level workings of the ISI in itself demonstrates the extent of the US intelligence community’s penetration of the Pakistani agency and its secrets.

Walk-in?

Under Hersh’s account, the walk-in provided the breakthrough intelligence that allowed the US government to begin putting together the assassination plan against bin Laden.

The evidence reviewed here shows that the US already had precise intelligence indicating bin Laden’s presence at the Abbottabad compound since 2008 at latest — yet the CIA failed to act on this information until an ISI officer walked into the US embassy and spilled the beans to CIA staff in return for a lucrative reward.

This means that neither the courier cover-story, nor the ISI walk-in, were the real sources of intelligence on bin Laden’s presence in Abbottabad. Rather, the numerous reports of his movements across Pakistan to meet leaders of various militant groups indicate that bin Laden was identifiable to multiple intelligence agencies months and years before the raid.

And there is no avoiding the fact that two months before the raid, information on bin Laden’s movements had come to the CIA via the intelligence agencies of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan — the very agencies involved in the secret operation to protect Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad.

Indeed, the US had obtained precise information on bin Laden’s movements from all its main regional allies, including Pakistan.

There are related anomalies. As national security reporter Gareth Porter points out, the retired Pakistani military officer, Brig. Gen. Qadir, found from interviews with locals in the area of bin Laden’s compound that there was no evidence whatsoever of the compound being guarded by the ISI, in a manner consistent with Hersh’s account of bin Laden being held captive. Security forces were nowhere to be seen guarding the complex.

In fact, during the course of his investigation, Qadir had also come across the same ‘walk-in’ story. But Qadir discounted it for being implausible in the fraught climate of Pakistan’s intelligence world.

“Qadir had picked up the walk-in story,” relates Porter, “complete with the detail that the Pakistani in question was a retired ISI officer who had been resettled from Pakistan — from American contacts in 2011.” In his book, the Brigadier General writes: “There is no way a Pakistani Brigadier, albeit retired, could receive this kind of money and disappear.” For such a betrayal, the ISI’s retaliation would be ruthless and immediate.

This suggests that the walk-in played a different role to that assumed by Hersh and his sources: rather than being instrumental in identifying bin Laden’s location, the walk-in was simply instrumental in triggering the events leading to his assassination: he blew the whistle on a highly compartmentalised intelligence operation, bringing bin Laden’s presence in the heart of Pakistan’s military intelligence community to the attention of disbelieving CIA staff in August 2010, and forcing the wider US intelligence community to take action.

Intelligence asset

Several compelling accounts confirm that bin Laden’s presence at the Abbottabad compound was sanctioned at the highest levels of Pakistani military intelligence. In the New York Times, Carlotta Gall reports that the “handling” of Osama bin Laden himself was a closely-guarded ISI operation, and that bin Laden himself was an ISI asset.

“According to one inside source, the ISI actually ran a special desk assigned to handle Bin Laden,” reports Gall.

“I learned from a high-level member of the Pakistani intelligence service that the ISI had been hiding Bin Laden and ran a desk specifically to handle him as an intelligence asset… It was operated independently, led by an officer who made his own decisions and did not report to a superior. He handled only one person: Bin Laden. I was sitting at an outdoor cafe when I learned this, and I remember gasping, though quietly so as not to draw attention. (Two former senior American officials later told me that the information was consistent with their own conclusions.) This was what Afghans knew, and Taliban fighters had told me, but finally someone on the inside was admitting it. The desk was wholly deniable by virtually everyone at the ISI — such is how supersecret intelligence units operate — but the top military bosses knew about it, I was told.”

This is possible due to layers of careful compartmentalisation, not just between the ISI and other government agencies, but also within the ISI itself.

“In 2007, a former senior intelligence official who worked on tracking members of al-Qaeda after Sept. 11 told me that while one part of the ISI was engaged in hunting down militants, another part continued to work with them.”

It is therefore not surprising that other ISI officials, although they knew that a raid was occurring, had no idea that the target was bin Laden. “They gave us a grid and told us that they were going there after ‘a high-value’ target. There are certain protocols when that happens — we take care of the outer security, while they go in and do their work. We certainly didn’t know who exactly was in there.” The same official, like US Army special operations veteran Jack Murphy, dismissed claims that the US had jammed Pakistani radars.

But certain senior ISI officials were involved. Corroborating Hersh’s account, in a report for Asia Times from 12th May 2011, Syed Saleem Shahzad reported that “Pakistan’s military and intelligence community was fully aware of and lent assistance to the United States mission to get a high-value target in Abbottabad.” But Shahzad’s sources also told him: “What it did not know was that it was Osama bin Laden who was in the crosshairs of US Special Forces.”

In reality, Shahzad’s sources did not know, but according to Hersh’s and Murphy’s sources, two Pakistani Generals did know bin Laden was the target. And Hersh’s sources specifically identified the officials as Pakistani Army chief Ashfaq Kayani and ISI Director-General Lieutenant Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha.

Shahzad’s previous report from before the raid had already put paid to the idea that bin Laden’s presence in Abbottabad was unknown to Pakistani intelligence. It showed that Saudi and Pakistani intelligence were tracking bin Laden’s meetings with militants on behalf of the CIA months before the raid — indicating that bin Laden’s presence and movements from his base in Abbottabad were known to senior ISI officials.

Shahzad’s May piece further corroborated Hersh’s account in reporting meetings between Pasha, Kayani, and US officials. Before the raid, he wrote, the US and Pakistan were negotiating a deal under which the US would have the unilateral right to conduct attacks on “high-value targets” like bin Laden and his deputy Dr Ayman al-Zawahiri, in return for “better economic deals” for Pakistan and “a greater role in the Afghan end game.”

To facilitate the deal, “top Saudi authorities” were called in, including “Prince Bandar bin Sultan,” to play a “pivotal role in fostering a new strategic agreement of which the Abbottabad operation was a part.”

As we shall see later, Saudi Arabia and Prince Bandar’s role in facilitating the agreement under which the Abbottabad raid took place is highly significant. During this negotiation period, bin Laden was already under extensive surveillance by US, Saudi, Pakistani, and Afghan intelligence.

Then in early April, ISI chief Ahmad Shuja Pasha visited the US to discuss “intelligence cooperation.” Shahzad’s security sources told him that “the new security arrangement” being negotiated between the US, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, “was high on the agenda.”

According to Hersh, a retired US government official was at that April meeting with Pasha: “Pasha told us at a meeting in April that he could not risk leaving bin Laden in the compound now that we know he’s there. Too many people in the Pakistani chain of command know about the mission… Of course the guys knew the target was bin Laden and he was there under Pakistani control.”

In the last week of April, Shahzad reported, the US’s top man in Afghanistan, Gen. David Petraeus, met with Pakistani military chief Gen. Kayani “and informed him of the US Navy Seals operation to catch a high-value target. The deal was done.”

By Hersh’s account, as early as January 2011, according to his retired US official, Kayani had agreed to a lethal strike on bin Laden: “He eventually tells us yes, but he says you can’t have a big strike force. You have to come in lean and mean. And you have to kill him, or there is no deal.”

That the ISI had a super secret unit dedicated solely to the task of ‘handling’ Osama bin Laden — and that “former senior American officials” had concluded the same — raises a host of issues. If bin Laden had a dedicated ISI handler, by definition he was operating as an agent on behalf of the ISI. And at least some senior US officials were aware of this.

If that is the case, then it also raises questions about the very nature of the intelligence sharing arrangements by which Pakistan was passing on intelligence to Americans relating to Abbottabad and Osama bin Laden.

How much did the Americans know about this operation? Reports from the Pakistan Foreign Ministry, Brigadier General Qadir, Syed Saleem Shahzad, among other sources, showed that Pakistan was routinely sharing intelligence on bin Laden’s movements and the Abbottabad compound with the US.

If Pakistani intelligence on bin Laden was, indeed, compartmentalised to a secret unit within the ISI under the authority of the most senior ISI officials, then the sharing of intelligence on his movements with the US (which apparently occurred about three months before the raid) could only have occurred as part of the same ‘handling’ arrangement, and with the approval of those officials — who would have exerted absolute control on how the ISI dealt with all intelligence related to bin Laden.

In internal emails obtained by Wikileaks, Stratfor’s Vice President for Intelligence Fred Burton — former deputy counter-terrorism chief at the State Department — told colleagues about information available to US government investigators:

“Mid to senior level ISI and Pak Mil with one retired Pak Mil General that had knowledge of the OBL arrangements and safe house. Names unk [unknown] to me and not provided. Specific ranks unk to me and not provided. But, I get a very clear sense we (US intel) know names and ranks.”

The leaked email stated that up to a dozen Pakistani ISI officials knew of bin Laden’s Abbottabad safe-house, and were in routine contact with the al-Qaeda chief.

In the context of the evidence already explored, the Stratfor correspondence suggests that contrary to official denials, US authorities not only knew that senior Pakistani military intelligence officers were harbouring Osama bin Laden since 2004, they knew that they were harbouring him in his Abbottabad compound for years, and by early 2011 they were working with the ISI in ongoing surveillance of the terror chief and his movements outside Abbottabad.

Collusion

Carlotta Gall’s account of bin Laden as an ISI intelligence asset is further corroborated by astonishing statements from former Pakistani Army and ISI chief, Gen. Ziauddin Butt, at a conference in October 2011.

Butt told conference attendees that bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad was in fact a safe-house used by a Pakistani intelligence agency, the Intelligence Bureau. He identified retired Intelligence Bureau chief Brigadier Ijaz Shah as the official responsible for keeping bin Laden there, with the knowledge and approval of Gen. Musharraf. If true, this would suggest that Brig. Ijaz Shah was bin Laden’s appointed ISI ‘handler.’

Lending credence to his claims, Pakistani intelligence officials had warned journalists present at the conference not to report Gen. Butt’s explosive revelations.

The Intelligence Bureau connection is crucial, as in the same NYT report, Gall refers to a Pakistani Interior Ministry Intelligence Bureau report documenting the surveillance of bin Laden’s movements outside Abbottabad to meet militants in 2009. This means that the intelligence unit that housed him was also the intelligence unit that monitored him.

Other senior ISI sources have also confirmed that bin Laden’s Abbottabad mansion was a safe-house used by the ISI. And a local police officer familiar with the compound said that the location was being used by Hizbul Mujahedeen, a militant group operating in disputed Kashmir, which has received extensive military and financial support from the ISI.

According to Pakistani security specialist Arif Jamal, writing for the Washington DC-based Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor journal, “As an ISI officer he [Ijaz Shah] was also the handler for Omar Saeed Sheikh, who was involved in the kidnapping of Wall Street Journal journalist Daniel Pearl in 2002. Omar Saeed Sheikh surrendered to Brigadier Shah who hid him for several weeks before turning him over to authorities.”

Jamal refers to an interview in 2000 with a Pakistani security official, who disclosed Shah’s relationship with Ahmed Omar Sheikh Saeed on condition of anonymity.

Brig. Shah’s connection to Omar Sheikh Saeed is deeply troubling. Sheikh Saeed was not simply accused of murdering Daniel Pearl — he was al-Qaeda’s finance chief during the 9/11 attacks. After 9/11, Indian intelligence officials confirmed that then ISI director Gen. Mahmoud Ahmad had ordered Omar Saeed to wire at least $100,000 to the chief 9/11 hijacker, Mohammed Atta.

As I documented in my books The War on Truth (2005) and The War on Freedom (2002), which was among 99 books selected for the 9/11 Commissioners to use as part of their inquiries, multiple US intelligence investigations corroborated the Indian allegations. US authorities had further confirmed that Sheikh Saeed had wired as much as $500,000 if not more to several of the 9/11 hijackers — all at the behest of the ISI. Despite this, US authorities took no measures to designate or extradite either Sheikh Saeed or his ISI boss, Mahmoud Ahmad.

As former British Cabinet Minister Michael Meacher observed: “It is extraordinary that neither Ahmad nor Sheikh have been charged and brought to trial on this count [of financing 9/11]. Why not?”

In his memoirs, In the Line of Fire, Gen. Musharraf revealed that Omar Sheikh Saeed was a MI6 agent who had executed certain missions on behalf of the British intelligence agency, before travelling to Pakistan and Afghanistan where he met Osama bin laden and Mullah Omar.

Sheikh Saeed was first recruited by MI6 while at the London School of Economics, recounts Musharraf. The agency persuaded him to join anti-Serb demonstrations during the Bosnia conflict, and later sent him to Kosovo to join the jihad. Musharraf argues that at some point, Saeed likely became “a rogue or double agent.”

Musharraf’s claims are no doubt self-serving, deflecting from the widely-reported fact that Sheikh Saeed was an ISI asset. But they chime with other facts in the public record.

Former US Justice Department prosecutor John Loftus, for instance, who held top secret national security clearances, has confirmed that MI6 was working with leaders of the now banned British group al-Muhajiroun — Omar Bakri Mohammed, Abu Hamza and Haroon Rashid Aswat (who would later become bin Laden’s bodyguard) — to recruit British Muslims to fight in Kosovo in 1996.

Sheikh Saeed would have been part of that MI6-backed funnel. Others in Musharraf’s government were convinced that Sheikh Saeed was also a CIA asset. In a little-noted article on Saeed’s murky background in March 2002, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review reported that: “There are many in Musharraf’s government who believe that Saeed Sheikh’s power comes not from the ISI, but from his connections with our own CIA.” Officials believe that “Saeed Sheikh was bought and paid for.”

Some senior US intelligence officials agree. John Newman, a former executive assistant to the director of the NSA who spent 20 years in the US Army Intelligence and Security Command, pointed out that despite Sheikh Saeed’s kidnapping of British citizens and related terror offenses, he faced no indictments from the US or Britain, and was even able to travel back to London in January 2000. He had also kidnapped American citizens, but faced no indictments from the US until after 9/11.

“Did the United States not indict Saeed Sheikh because he was a British informant? Did the agency [CIA] receive information provided by Saeed Sheikh from British or Pakistani intelligence?” asked Newman rhetorically at a 2005 Congressional briefing on the findings of the 9/11 Commission Report.

“This would help explain why Saeed Sheikh was not indicted and escaped justice for his crimes and traveled freely around England… If the foregoing analysis has any merit, Western intelligence agencies were receiving reports from a senior al-Qaeda source. Once again, however, al-Qaeda had used Western intelligence to accomplish its own mission. Saeed Sheikh was probably a triple agent.”

Ahmed Omar Sheikh Saeed’s role in the 9/11 attacks on behalf of the head of the ISI, Newman noted, was completely ignored by the 9/11 Commission Report. But the revelation that Sheikh Saeed was likely a triple agent of the ISI, CIA and MI6, also raises questions about bin Laden’s protection by the ISI after 9/11. The failure of US authorities to out Sheikh Saeed’s 9/11 role suggests that his freedom of movement before 9/11 was very much enabled by what Newman describes as his “triple agent” status.

In other words, bin Laden and Sheikh Saeed — apparently a CIA and MI6 asset — shared the same ISI handler, Brig. Ijaz Shah.

Newman argues, essentially, that the Sheikh Saeed story shows how US and British determination to maintain an intelligence asset in the heart of bin Laden’s operations, gave him and his associates an extraordinary freedom of impunity that blew up in our faces on 9/11.

Our jihadists

The Saudi-Pakistani arrangement at Abbottabad provided bin Laden with significant freedom of movement, and an ability to continue maintaining direct contact with al-Qaeda militants. Yet it also coincided with the acceleration of a covert US strategy launched to empower Sunni jihadists.

Around the middle of the last decade, the Bush administration decided to use Saudi Arabia to funnel millions of dollars to al-Qaeda affiliated jihadists, Salafi militants, and Muslim Brotherhood Islamists. The idea was to empower these groups across the Middle East and Central Asia, with a view to counter and rollback the geopolitical influence of Shi’ite Iran and Syria.

Seymour Hersh himself reported in detail on the unfolding of this strategy in the New Yorker in 2007, citing a range of US and Saudi government, intelligence and defence sources. The US-backed Saudi funding operation for Islamist militants, including groups affiliated with or sympathetic to al-Qaeda, was active as far back as 2005 according to Hersh — the same year that bin Laden’s move to Abbottabad under Saudi financial largess was approved.

The thrust of Hersh’s 2007 report has been widely confirmed elsewhere, including by several former senior government officials speaking on-the-record.

The existence of a US covert programme of this nature was corroborated by ABC News that very year.

Then in 2008, a US Presidential Finding disclosed that Bush had authorised an “unprecedented” covert offensive against Iran and Syria, across a huge geographical area from Lebanon to Afghanistan, permitting funding to anti-Shi’a groups including Sunni militant terrorists like the pro-al-Qaeda Jundullah, Iranian Kurdish nationalists, Baluchi Sunni fundamentalists, and the Ahwazi Arabs of southwest Iran. The CIA operation would receive an initial influx of $3–400 million.

Although spearheaded under Bush, the strategy escalated under the Obama administration.

Alastair Crooke, a retired 30-year MI6 officer and Middle East advisor to EU foreign policy chief Javier Solana, explained that the US-Saudi alliance would generate a resurgence of al-Qaeda jihadists:

“US officials speculated as to what might be done to block this vital corridor [from Iran to Syria], but it was Prince Bandar of Saudi Arabia who surprised them by saying that the solution was to harness Islamic forces. The Americans were intrigued, but could not deal with such people. Leave that to me, Bandar retorted.”

This regional strategy, Crooke said, involved the sponsorship of extremist Salafis in Syria, Libya, Egypt, Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq “to disrupt and emasculate the [Arab Spring] awakenings that threaten absolute monarchism.”

The continuation of the strategy under Obama was also confirmed by John Hannah, former national security advisor to Vice President Dick Cheney, who remarked that:

“Bandar working as a partner with Washington against a common Iranian enemy is a major strategic asset.”

Mobilising extremist Sunnis “across the region” under “Saudi resources and prestige,” wrote Hannah, can “reinforce US policy and interests… weaken the Iranian mullahs; undermine the Assad regime; support a successful transition in Egypt; facilitate Qaddafi’s departure; reintegrate Iraq into the Arab fold; and encourage a negotiated solution in Yemen.”

The activation of the strategy was perhaps most clearly confirmed in a 2008 US Army-sponsored RAND Corp report, which recommended eight strategies for prosecuting the ‘war on terror’ in the region.

Among them was a recommendation to exploit “fault lines between the various SJ [Salafi-jihadist] groups to turn them against each other and dissipate their energy on internal conflicts,” for instance between “local SJ groups” focused on “overthrowing their national government” and transnational jihadists like al-Qaeda. The US “could use the nationalist jihadists to launch proxy IO [information operation] campaigns to discredit the transnational jihadists.”

The US could also “choose to capitalise on the Shia-Sunni conflict by taking the side of the conservative Sunni regimes in a decisive fashion and working with them against all Shiite empowerment movements in the Muslim world… to split the jihadist movement between Shiites and Sunnis.” The US would need to contain “Iranian power and influence” in the Gulf by “shoring up the traditional Sunni regimes in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Pakistan.”

Although this would mean empowering al-Qaeda’s chief financial backers among Sunni states, the widening Sunni-Shia sectarian conflict would “reduce the al-Qaeda threat to US interests in the short term,” by diverting Salafi-jihadist resources toward “targeting Iranian interests throughout the Middle East,” especially in Iraq and Lebanon, hence “cutting back… anti-Western operations.”

The same US Army-backed RAND report confirmed that this “divide and rule” strategy had already been activated in the region, specifically in Iraq:

“Today in Iraq such a strategy is being used at the tactical level, as the United States now forms temporary alliances with nationalist insurgent groups that it has been fighting for four years… In the past, these nationalists have cooperated with al-Qaeda against US forces.”

Bringing all this together implies that in the same year that the Pakistani ISI received funding from Saudi Arabia to harbour bin Laden in his custom-built mansion in Abbottabad, the US had covertly partnered with Saudi Arabia to support al-Qaeda affiliated groups as part of a highly clandestine divide-and-rule strategy to counter Iranian influence.

Quoting Hersh from his 2007 report, a US government consultant told him that Prince Bandar bin Sultan and other Saudis had assured the White House that:

“… they will keep a very close eye on the religious fundamentalists. Their message to us was ‘We’ve created this movement, and we can control it.’ It’s not that we don’t want the Salafis to throw bombs; it’s who they throw them at — Hezbollah, Moqtada al-Sadr, Iran, and at the Syrians, if they continue to work with Hezbollah and Iran.”

Thus, the key US contact in Saudi Arabia responsible for the covert ‘redirection’ strategy at its origination was Prince Bandar bin Sultan, then Secretary-General of Saudi’s National Security Council.

As reported by Saleem Shahzad, Prince Bandar — who knew bin Laden personally from their Cold War days — had also met with US and Pakistani officials in the months leading up to the bin Laden raid.

In other words, Prince Bandar was the same senior Saudi official who helped negotiate the agreement under which the Abbottabad operation would be executed in 2011, and who had been tapped under both Obama and Bush to accelerate Saudi funding of Islamist militants to counter Iran.

Yet US officials knew that Bandar was linked directly to the events of 9/11. In tapping the Prince to assist with the anti-Iran strategy and the Pakistan-bin Laden strategy, US officials knowingly collaborated with a Saudi royal who had financed the 9/11 hijackers.

In his book Intelligence Matters (2004), Senator Bob Graham, co-chair of the Congressional Inquiry into 9/11, discusses the contents of a top secret CIA memo dated 2nd August 2002 about two 9/11 hijackers, Khalid Almihdhar and Nawaf Alhazmi. The CIA memo concluded that there is “incontrovertible evidence that there is support for these terrorists within the Saudi government.”

The 28 page section of the Congressional report including discussion of the CIA memo was classified, but some of its contents were leaked, and related issues revealed in press reports. Early in 2000, when Almidhar and Alhazmi arrived at Los Angeles airport, they were picked up by a fellow Saudi, Omar al-Bayoumi, who gave them $1,500 in cash, moved them into his apartment building, and helped them apply for flight school.

Al-Bayoumi worked for Dallah Avco, a Saudi-based airline chaired by Prince Bandar’s father, Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz. The firm is a major contractor for the Saudi Ministry of Defense and Aviation.

In the following months, al-Bayoumi and his associates received regular cashier’s cheques of around $2,000 a month, totaling tens of thousands of dollars. These came from Prince Bandar and his wife, Princess Haifa bint Faisal. Both Bandar and his wife claimed the money was donated for charitable purposes (one payment track was made after one of al-Bayoumi’s associates requested assistance from the Saudi embassy for thyroid treatment), and that they had no idea it was being diverted to fund the 9/11 hijackers.

After 9/11, British authorities questioned al-Bayoumi in London about the Saudi money trail to bin Laden’s hijackers. They had discovered secret papers with the private phone numbers of senior Saudi government officials concealed beneath the floorboards of his flat in London. The investigation went nowhere: al-Bayoumi was soon released, and disappeared into Saudi Arabia.

This disturbing background shows that Prince Bandar was connected to the 9/11 attacks, but protected by US authorities; that he was the White House’s point-man to launch the wider US-Saudi covert arrangement to fund al-Qaeda affiliated groups (coinciding with bin Laden’s move to Abbottabad with Saudi funding); and that by 2011, he was privy to Pakistan’s harbouring of al-Qaeda’s leader and the US-Pakistan arrangement that led to his assassination.

Throughout this period, senior US intelligence officials have said that Osama bin Laden was actively engaged in directing the very al-Qaeda terror activity that Saudi Arabia was busy financing, while also financing bin Laden’s ISI-controlled base in Abbottabad.

“This compound in Abbottabad was an active command and control center for al Qaeda’s top leader and it’s clear… that he was not just a strategic thinker for the group,” said one official. “He was active in operational planning and in driving tactical decisions.”

That claim is consistent with information on bin Laden’s activity contained in the Afghan War logs. The overwhelming implication, and the consistent role of Prince Bandar in the alignment of these events, is that the US-backed Saudi programme to “control” who bin Laden-affiliated Salafis “throw bombs” at, gave bin Laden a free-hand to accelerate his terrorist activity under the auspices of the ISI.

The US-led strategy had, it seems, enabledthe Saudi-Pakistani arrangement with the al-Qaeda founder as a matter of geopolitical convenience to undermine Iran.

The great escape

Credible reports of bin Laden’s connections to the Haqqani network also point to the role of the Saudi and Pakistani states in protecting bin Laden.

Two months before the US raid on his Abbottabad mansion, a BBC interview with senior officials of the Haqqani network confirmed a meeting with Osama bin Laden in Chitral in the northwest Pakistan frontier region.

The Haqqani network points directly to the ISI. In his testimony before the US Senate in September 2011, then outgoing chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, said that “credible intelligence” confirms that “the Haqqani network… acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency.”

This intelligence goes back many years. In 2008, for instance, confidential NATO reports and US intelligence assessments circulated among senior White House officials confirmed that Pakistan’s ISI at the highest levels had provided military support to Taliban insurgents, particularly the Haqqani network. Gen. Ashfaq Kayani, who according to Hersh was complicit in protecting bin Laden in Abbottabad, had been identified as sanctioning provision of military aid to insurgents affiliated to bin Laden.

In fact, US and British intelligence analyses from just before 9/11 right up until the bin Laden raid not only show that the ISI has supported such al-Qaeda linked insurgent groups in Pakistan and Afghanistan throughout that period, but that US and British officials were well aware of the same.

Various credible sources report that the Haqqani network, with assistance from the ISI, had played a key role in bin Laden’s escape from the Tora Bora complex in 2001 into Pakistan in the wake of the US bombing campaign.

In the New Yorker, Dexter Filkins cites Afghanistan’s intelligence chief from 2004 to 2010, Amrullah Saleh, who told him that ISI operative Syed Akbar Sabir had escorted bin Laden from Chitral to Peshawar in Pakistan: “We believed that he was part of the ISI operation to care for bin Laden.”

Another ISI agent, Fida Muhammad, had confessed to the Afghans that he had been escorting Haqqani insurgents from Pakistan into Afghanistan to fight the NATO occupation for the previous decade. But his most “memorable” job was in December 2001, when he participated in a major ISI covert operation — sanctioned at the highest levels — to help al-Qaeda fighters escape from Tora Bora.

There were dozens of ISI teams operating on the ground at the time who successfully evacuated as many as 1,500 militants from Tora Bora and other jihadist camps.

In his New Yorker story, Filkins quotes former CIA counter-terrorism officer Bruce Riedel on former ISI chief Nadeem Taj, whom he described as being “deeply involved with Pakistani militants, particularly those fighting against India.”

But as Filkins observes:

“Before taking over the ISI, Taj was the commandant of the Pakistani military academy in Abbottabad. That is, he was the senior military official in Abbottabad at the time that American officials believe bin Laden began living there. Taj retired from the Pakistani Army in April, just days before the raid in Abbottabad. Attempts to track him down in Pakistan were unsuccessful.”

According to a 2009 Senate Committee on Foreign Relations report into the Tora Bora debacle, US intelligence had confirmed bin Laden’s presence among al-Qaeda fighters, during the December 2001 bombing campaign — a matter confirmed by the official history of the US Special Operations Command.

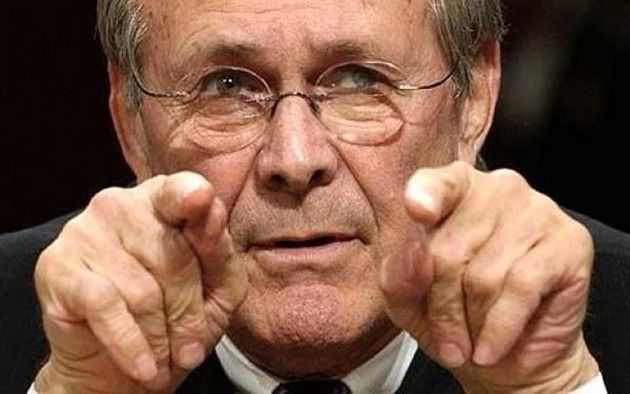

Yet the commander of the operation, General Tommy Franks, Vice President Dick Cheney, and other senior officials claimed falsely that “the intelligence was inconclusive about the Al Qaeda leader’s location.”

Gen. Franks to this day justifies the decision on an outright lie: “I have yet to see anything that proves bin Laden or whomever was there.”

In reality, the Senate report proves that White House and military officials knew bin Laden was there, and were warned repeatedly that the failure to mobilise US forces to block the wide-open routes into Pakistan would result in his escape.

Henry Crumpton, head of special operations for the CIA’s counter-terrrorism division and chief of its Afghan strategy, had told the Bush administration that “we’re going to lose our prey [bin Laden]” without bringing in US marines already stationed in Kandahar to block those routes.

“The decision not to deploy American forces to go after bin Laden or block his escape,” the Senate report noted, “was made by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and his top commander, General Tommy Franks.”

“The implications of these statements are that bin Laden was alive and was allowed to escape,” said Prof. Sunil Ram of the American Military University, writing in the respected Canadian defence journal, Frontline Defence.

Just a month earlier, the Pentagon was directly complicit in secret Pakistani military airlifts into Kunduz which rescued beleaguered Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters from America’s elite Delta Force units on the ground. A CIA official and a Delta Force military analyst told Seymour Hersh for the New Yorker that “the Administration ordered the United States Central Command to set up a special air corridor to help insure the safety of the Pakistani rescue flights.”

The operation was purportedly undertaken to save Pakistani military and intelligence operatives on the ground in Kunduz, whose deaths under US bombing would jeopardise the political survival of Pakistan’s then leader, Gen. Pervez Musharraf.

Yet on 21st November, in response to questions from journalists about reports of the airlifts, Rumsfeld denied the Pentagon’s involvement while also inadvertently revealing his knowledge of the operation’s foreseeable consequences:

“Any idea that those people should be let loose on any basis at all to leave that country and to go bring terror to other countries and destabilise other countries is unacceptable.”

In other words, senior White House and Pentagon officials were complicit in ISI operations that foreseeably “let loose” Laden’s Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters to “go bring terror to other countries.”

According to Prof. Ram, who was a senior military strategy advisor to the Saudi Royal family for over a decade:

“The Battle of Tora Bora obviously raises the question why was he [bin Laden] allowed to escape? … if US Special Forces had killed or captured him in Tora Bora in 2001, the basic justification for the Global War on Terror would have been eliminated and the subsequent (and false) claims of links between al-Qaeda and Iraq would have been meaningless.”

He points out that many of the “expansionist policies” subsequently pursued by the Bush administration as outlined by the neoconservative think-tank, the Project for a New American Century, would have had little traction had al-Qaeda been routed and bin Laden killed in Tora Bora.

“The US would have been hard pressed to convince anyone of the need to invade Iraq or continue the war in Afghanistan,” concludes Ram, who was previously an editor at SITREP, the defence journal of the Royal Canadian Military Institute, where he sat on the Defence Studies Committee. “Thus, logic dictates that bin Laden was allowed to escape into Pakistan in late 2001.”

The Haqqani network, which appeared to have been integral to the post-9/11 ISI operation “to care for bin Laden,” to quote Afghanistan’s former intelligence czar, Amrullah Saleh, also remains connected to Saudi Arabia.

The latest batch of confidential Saudi diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks contains documents revealing that the Saudi ambassador to Pakistan met in February 2012 with Nasiruddin Haqqani, the jihadist group’s chief fundraiser at the time, and the son of Jalaluddin Haqqani, the group’s founder. Nasiruddin was later killed in a shooting in Islamabad in November 2013.

The documents show that Nasiruddin asked the Saudi ambassador to convey to the Saudi king his father’s wish for treatment in a Saudi hospital, and mentions that Jalaluddin Haqqani holds a Saudi passport. Another document shows that a senior Saudi foreign ministry official then recommended that the treatment go ahead — although it remains unclear whether it actually did.

Previous US diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks confirmed US intelligence has been well aware for years that Taliban and Haqqani network fundraisers and associates were routinely residing in or travelling to Saudi Arabia, where they engaged in fundraising activities.

While documenting apparent Saudi cooperation with the US to disrupt terror support activities inside Saudi Arabia, the new leaked Saudi cables show that Saudi officials at the highest level are still courting the same militant networks abroad.

In other words, senior Saudi and Pakistani government officials until well after the bin Laden raid have retained close ties to the Haqqani network — the same network which under ISI purview facilitated bin Laden’s escape from Tora Bora in 2001, and with which bin Laden met just months before the May 2011 raid.

The split

But despite bin Laden’s ongoing involvement in directing militant activity, often in liaison with groups supportive of al-Qaeda like the Haqqani network, there can be little doubt that his role in al-Qaeda had significantly reduced.

According to Pakistani tribal sources cited by Gareth Porter who were familiar with bin Laden’s presence in South Waziristan shortly after 9/11, bin Laden had been increasingly sidelined by other al-Qaeda leaders, including his deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri.

But Porter vastly overstates his case in arguing that bin Laden’s role in al-Qaeda had become virtually mute — an idea put forward by the US West Point Military Academy’s Counter Terrorism Center which released the bin Laden files.

The latest detailed analysis of the documents from the Abbottabad compound show that bin Laden had overseen the dispatch of al-Qaeda forces across the Middle East from Yemen to Libya, where for instance one of his deputies informed him of “an active Jihadist Islamic renaissance underway in Eastern Libya (Benghazi, Derna, Bayda and that area).”

The Abbottabad documents also confirmed that in the months before bin Laden’s death, al-Qaeda’s leadership and sponsors in the Pakistani ISI were — as with Hekmatyar — actively seeking some sort of accommodation with the Americans.

The documents recorded former ISI chief Hamid Gul telling his al-Qaeda contacts: “We are putting pressure on them [America] to negotiate with al-Qaeda . . . [and] that negotiating with the Taliban separate from al-Qaeda is pointless.”

But the most intriguing revelation is that Bin Laden’s deputy, Atiyah Abd al-Rahman, told bin Laden in early 2011 that UK security services were in contact with Libyan al-Qaeda operatives in Britain:

“British Intelligence spoke to them (these Libyan brothers in England), and asked them to try to contact the people they knew in al Qaeda to inform them of and find out what they think about the following idea: England is ready to leave Afghanistan [if] al Qaeda would explicitly commit to not moving against England or her interests.”

This proposal had been relayed through an al-Qaeda operative in Libya, then in hiding in Iran, who was in contact with “some Libyan brothers in England.”

It should be noted that in 2007, documents leaked by Snowden showed that the NSA had acknowledged tracking a “communications path” from Osama bin Laden in Pakistan to al-Qaeda leaders in Iraq and Iran.

The new proposal offered a repeat of what British security officials have described as an informal ‘covenant of security’ with Islamists that had been in place during the Cold War and through the 1990s.

According to Lieutenant Colonel Crispin Black, a former UK Cabinet Office intelligence advisor to the Prime Minister, under the ‘covenant of security’ Islamist militants would be able to reside unmolested in Britain and plot to their hearts’ content, as long as they refrained from targeting Britain or British interests.

Al-Rahman went on in the letter to explain how he had already responded to the British proposal:

“I wrote: we can consider the matter and come up with something appropriate along this vein. I will convey the idea to the leadership. He may have told the Libyan brothers by now, and they may have told the British.”

However, bin Laden was intent on rejecting the proposal. A letter to al-Rahman from bin Laden dated 26th April 2011 records the latter’s conviction that UK forces were “sure of being defeated”:

“Regarding what you mentioned about the British intelligence saying that England is going to leave Afghanistan if al-Qaeda promised not to target their interests… I say that we do not enable them on that, but without slamming the door completely closed.”

For bin Laden, the emphasis was on avoiding any such accommodations with the West, telling al-Rahman: “We would like to neutralise whomever we possibly can during our war with our bigger enemy, America.”

Al-Qaeda had, in that context, offered a truce to bin Laden’s Pakistani benefactors, on condition that they cease cooperation with the US: “You became part of the battle when you sided with the Americans. If you were to leave us and our affairs alone, we would leave you alone.”

Extraordinarily, bin Laden was able to use his position from Abbottabad to freely threaten Pakistan with further domestic al-Qaeda terrorist attacks due to the government’s ongoing coordination with the Americans.

The documents show that bin Laden remained obsessed with organising a “large operation inside America [that] affects the security and nerves of 300 million Americans.”