A new United Nations report published this February has criticised prevalent approaches to countering ‘radicalisation’ as ineffective, conceptually flawed, and more likely to reinforce extremist narratives than prevent them.

The report to the UN Human Rights Council is authored by Ben Emmerson QC, the UN Special Rapporteur on Counter Terrorism and Human Rights.

Emmerson is a leading British lawyer, deputy High Court Judge, and British judge on the Residual Mechanism of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

His new report to the UN criticises “[m]any programmes directed at radicalisation” for being “based on a simplistic understanding of the process as a fixed trajectory to violent extremism with identifiable markers along the way.”

Despite volumes of research and huge expenditures, he points out, “there are no authoritative statistical data on the pathways towards individual radicalisation.”

To make matters worse, Emmerson concludes, “States have tended to focus on those [approaches] that are most appealing to them, shying away from the more complex issues, including political issues such as foreign policy and transnational conflicts.” This has led to a misguided “focus on religious ideology as the driver of terrorism and extremism”, and an escalating resort to repressive and discriminatory measures targeted at Muslim communities.

Far from preventing extremism, this is fuelling it. Emmerson refers to an earlier warning from the UN Human Rights Commissioner that “any more repressive [an] approach would have the reverse effect of reinforcing the narrative of extremist ideologies”, and warns that this is precisely what is now coming to pass.

80% of terrorism studies are bullshit

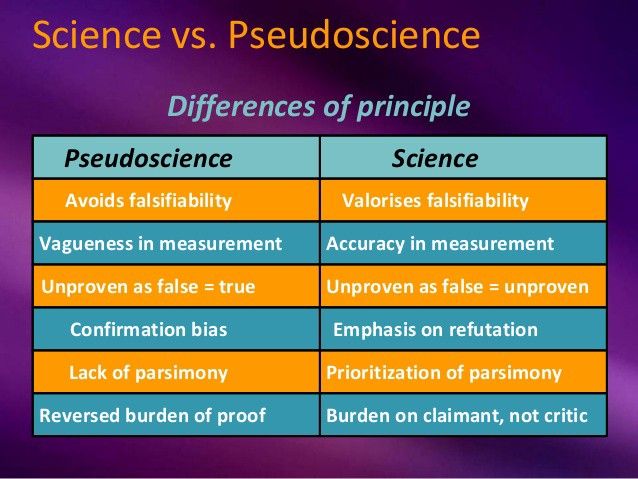

Yet this important UN report barely scratches the surface of how truly crap the state of the science is when it comes to understanding what ‘radicalisation’ even is, let alone countering it.

Over thirty years ago, Alex P. Schmid, former Office-in-Charge of the UN’s Terrorism Prevention Branch and Albert Jongman of Leiden University’s PIOOM Foundation (Interdisciplinary Research Programme on Root Causes of Human Rights Violations) reviewed over 6,000 academic studies of terrorism published between 1968 and 1988. Shockingly, as they explained in their seminal book Political Terrorism, they found that “perhaps as much as 80 percent of the literature is not research-based in any rigorous sense.”

Of course, that’s a very polite, typically academic way of putting it.

The thing is, when an academic tells you that your work is “not research-based in any rigorous sense”, what she’s basically saying is that your work has very little, if any, scholarly merit. It doesn’t actually make an original contribution to knowledge.

In short, for all intents and purposes, it’s bullshit.

When evidence is lacking: recycle

In any other discipline, academic research that is “not research-based in any rigorous sense” would mean you fail to get your degree — let alone fail to get published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Not in terrorism studies.

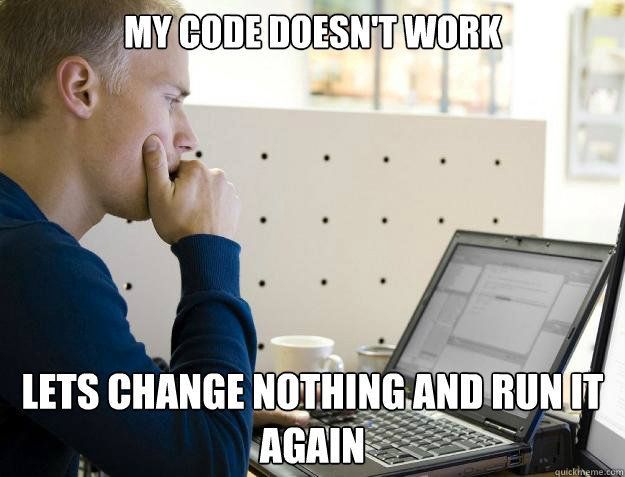

In terrorism studies, decades of ‘scholarship’ that is “not research-based in any rigorous sense” is being continuously recycled to regurgitate ‘new’ theories and policy recommendations which, however, have little if any evidential support.

By 2001, Professor Andrew Silke of the University of East London — a counter terrorism specialist who advises the UN and the UK government’s Cabinet Office — wrote in the journal Terrorism and Political Violence that the situation had still barely improved.

Despite decades of scholarship, he concluded, terrorism studies still struggled “in its efforts to explain terrorism or to provide findings of genuine predictive value.”

Most of the ‘scientific’ literature on terrorism, Silke found, recycled information from previous secondary sources, with only about 20% of publications offering genuinely original and novel data.

When Silke updated his analysis of the field in his contribution to the 2009 Routledge anthology, Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda, he found that despite some marginal progress, the field was still characterised largely by an over-reliance on secondary sources and a dearth of empirical data.

Numerous other terrorism experts have admitted this problem. A 2006 report by the NATO Programme for Security in Science, Tangled Roots: Social and Psychological Factors in the Genesis of Terrorism, examined 1535 academic papers on terrorism between 2000 and 2004. It concluded:

“… a careful review reveals that genuine new data was reported in less than 10% of that subgroup.”

Other reviews have been even more damning. That year, a major study of the literature in Campbell Systematic Reviews concluded that “only 3% of articles from peer-reviewed sources appeared to be based on some form of empirical analysis.” Another 1% consisted of case studies, and the remaining 96% consisted essentially of “thought pieces.”

Which means that a whopping 96% was recycled bullshit.

That was ten years ago, so have things gotten better since then?

Pseudo-science echo chamber

Not really.

In 2011, Professor Adam Dolnik, Director of Terrorism Studies at the Centre for Transnational Crime Prevention (CTCP) at the University of Wollongong in Australia, observed in Perspectives on Terrorism that the continual dependence on secondary sources means that terrorism studies represents a “highly unreliable closed and circular research system, functioning in a constantly reinforcing feedback loop.”

The continual transmission of contradictory truisms within the field, has meant that terrorism experts are not really advancing knowledge of terrorism or extremism, and how to deal with it — they’re just repeating the same stale assumptions and prescriptions again and again.

Of course, that’s not to say that all terrorism research is useless. There is good research going on — but it’s few and far between, and the best work doesn’t necessarily impact on policy.

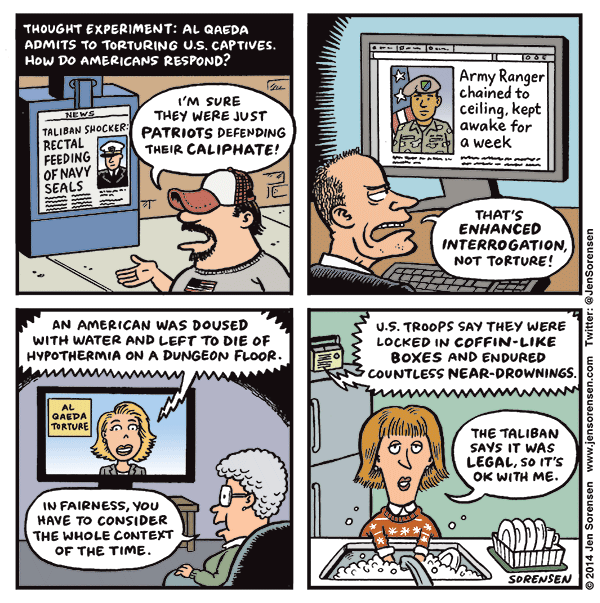

In any other discipline, the chronic inability to produce meaningful and original contributions to knowledge would justify wholesale dismissal as the work of cranks and pseudo-scientists.

Unfortunately, the one saving grace is that when the best counter-terrorism specialists are able to apply scientific standards to the field, among the most consistent findings is that the field is full of very serious, beard-stroking, speculative conjecture dressed up as ‘theory.’

In 2013, a background note by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in The Hague conceded that, despite some important improvements in the gathering of empirical data:

“A lack of research based on primary sources has been one of the major impediments to progress in the field of (counter-) terrorism studies… As numerous leading experts have warned, the consequences of an overreliance on secondary sources of information, such as newspapers, has led to a great amount of theorising based on a perilously small empirical foundation.”

That year, the Scientific Approach to Finding Indicators of and Responses to Radicalisation (SAFIRE) project of the leading Pentagon contractor RAND Europe similarly found that despite offering “numerous insights into the process of violent radicalisation… only a minority of the literature consisted of empirical and/or causal research, which could explain the causes of violent extremism and terrorism.”

Ironically, this has the effect that all these wonderful “insights” may really just be reflections of the prejudices of those involved in the research:

“In other words, one can only have limited confidence that the results from the literature accurately reflect the characteristics of the violent extremist and terrorist population, and not the assumptions and biases of those that have reported the characteristics of violent extremists and terrorists to the researchers.”

This is another polite, academic way of admitting that the bulk of the literature is full of unsubstantiated, self-referential bullshit — while also trying to project a semblance of scholarly credibility.

“The lack of causal research in relation to factors associated with violent extremism and terrorism suggests that the findings from the literature cannot, on the whole, be used to explain what drives people to violent extremism or terrorism or to predict outcomes,” concluded the SAFIRE report.

Translation: the, ahem, “findings” from the literature cannot, on the whole, be treated as actual scientific “findings” that can “explain” or “predict” anything concerning extremism or terrorism.

Forensic psychiatrist and former CIA operations officer Marc Sageman was far more harsh in his 2014 review published in Terrorism and Political Violence.

“Despite over a decade of government funding and thousands of newcomers to the field of terrorist research, we are no closer to answering the simple question of ‘What leads a person to turn to political violence?’” he lamented.

He blamed this “state of stagnation” on government funding of academic research while still withholding access to sensitive primary source information guarded by the intelligence community:

“This has led to an explosion of speculations with little empirical grounding in academia, which has the methodological skills but lacks data for a major breakthrough… Nor has the intelligence community been able to achieve any breakthrough because of the structure and dynamic of this community and its lack of methodological rigor. This prevents creative analysis of terrorism protected from political concerns.”

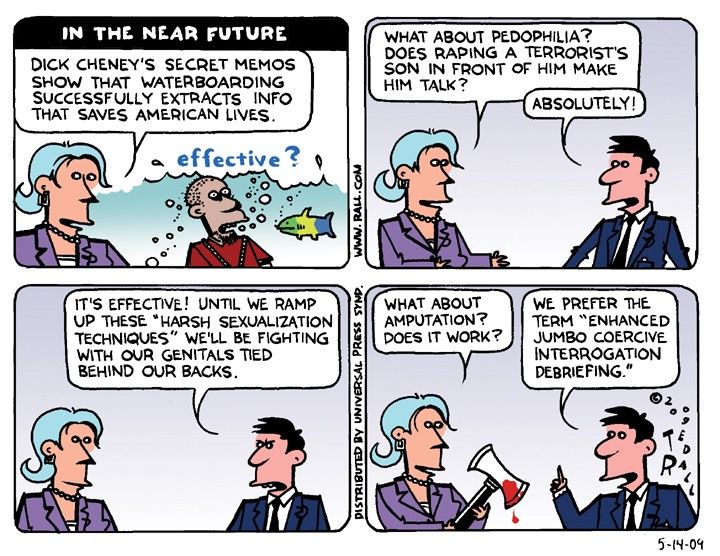

Sageman’s answer is for governments to give academics access to sensitive data gleaned from the intelligence community, such as evidence from interrogations of detained extremists and terrorists. That’s assuming that, somehow, such intelligence is not itself compromised or politicised.

This was, of course, the case with much of the 9/11 Commission Report. My first book, The War on Freedom: How & Why America was Attacked, September 11, 2001, was among 99 books made available to the 9/11 Commissioners as part of their investigations. It was also the first book read by the Jersey Girls, the well-known group of 9/11 widows who had played a key role in the 9/11 Family Steering Committee, which set out key lines of inquiry for the Commission to explore.

Yet according to NBC News, more than a quarter of the final report’s footnotes refer to interrogations of detainees acquired by torture, including three alleged senior al-Qaeda leaders who were repeatedly waterboarded.

As Philip Shenon observed in Newsweek:

“This has troubling implications for the credibility of the commission’s final report. In intelligence circles, testimony obtained through torture is typically discredited; research shows that people will say anything under threat of intense physical pain.”

Among these sources, one of the main ones is ‘Abu Zubaida’, whose real name is Zain al-Abidin Mohamed Hussein. Zubaida in particular is repeatedly referenced throughout the 9/11 Commission Report, where he is described as a key operational planner of the 9/11 attacks, a senior al-Qaeda lieutenant and operations chief, a close associate of Osama bin Laden, and so on.

But according to Daniel Coleman, a 31-year veteran FBI agent intimately familiar with Abu Zubaida’s case, the terror suspect was, in fact, mentally ill:

“Looking at other evidence, including a serious head injury that Abu Zubaida had suffered years earlier, Coleman and others at the FBI believed that he had severe mental problems that called his credibility into question. ‘They all knew he was crazy, and they knew he was always on the damn phone,’ Coleman said, referring to al-Qaeda operatives. ‘You think they’re going to tell him anything?’… Much of the threat information provided by Abu Zubaida, Coleman said, ‘was crap.’”

Coleman would also tell Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Ron Suskind:

“This guy is insane, certifiable, split personality.”

Zubaida’s claims under torture led to multiple new arrests of other alleged senior al-Qaeda leaders and whole new reams of investigation, much of which also ended up as part of the narrative put out in the 9/11 Commission Report. Dozens of other ‘terror suspects’ detained at Guantanamo (and eventually released without charge) had been linked to him.

Yet by 2009, even the US government was forced to concede that its entire narrative about Zubaida was basically, largely, bullshit. According to the transcript of court proceedings that year:

“The Government has not contended in this proceeding that Petitioner [Abu Zubaida] had any direct role in or advance knowledge of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.”

Er, say what?

The US government went on to concede that Zubaida was not involved in any other previous terrorist attacks, was not actually a member of al-Qaeda, and was not even a member of the Taliban.

“… for purposes of this proceeding the Government has not contended that Petitioner had any personal involvement in planning or executing either the 1998 embassy bombings in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, or the attacks of September 11, 2001…

“… the Government has not contended in this proceeding that Petitioner was a member of al-Qaida or otherwise formally identified with al-Qaida… Respondent does not contend that Petitioner was a ‘member’ of al-Qaida in the sense of having sworn bayat (allegiance) or having otherwise satisfied any formal criteria that either Petitioner or al-Qaida may have considered necessary for inclusion… Nor is the Government detaining Petitioner based on any allegation that Petitioner views himself as part of al-Qaida as a matter of subjective personal conscience, ideology, or worldview… The Government does not contend in its factual return that Petitioner was a ‘member’ of the Taliban…”

The government thus effectively erased the entirety of its own narrative about the operational planning behind the 9/11 terrorist attacks, rendering the vast bulk of the 9/11 Commission Report’s findings null and void.

No wonder Zubaida remains indefinitely detained without charge in Guantanamo — imagine the impact of a trial forcing the US government to release him: it would amount to an official admission that the White House-sanctioned narrative of the 9/11 operation is largely a torture-driven fantasy of CIA and Bush administration sadists.

So what exactly, then, is the US government contending? Not much, according to the court transcript:

“Rather, Respondent’s [the US government’s] detention of Petitioner [Abu Zubaida] is based on conduct and actions that establish Petitioner was ‘part of’ hostile forces and ‘substantially supported’ those forces.”

Whatever this means — and the US government has still refused to charge Zubaida, who is currently detained in Guantanamo — it is somewhat consistent with Suskind’s conclusion:

“Zubaydah was a logistics man, a fixer, mostly for a niggling array of personal items. Like the guy you call who handles the company health plan, or benefits, or the people in human resources. There was almost nothing ‘operational’ in his portfolio. That was handled by the management team. He wasn’t one of them.”

So essentially, this is the sort of deeply compromised ‘intelligence’ that terrorism scholars imagine might help them do more scientifically robust research.

Further translation: it’s pretty much all bullshit. So please give us more funding to try and turn this decades of mounting bullshit into gold; and some more ‘intelligence’ because at least then we can maintain a semblance of credibility by pointing to ‘primary sources.’

Dithering over Violent Extremism (DVE)

No wonder, then, that the policy recommendations that emerge from the field appear to have achieved very little — if not failed dramatically.

This is unambiguously clear from the practical results of a burgeoning sub-field of terrorism studies: preventing or countering violent extremism (PVE or CVE).

Understandably, given governments’ eagerness to be seen by their publics to be ‘doing something’ about terrorism, a veritable industry has ballooned around the urgent task of creating community-level strategies that stop people from being radicalised in the first place.

But like the wider field of terrorism studies, the scientific evidence that prevailing PVE/CVE strategies actually work is thin, to say the least.

You won’t hear government spokespersons admitting this in any formal capacity — but internal assessments and reviews tend to show that privately, the bankruptcy of existing CVE programmes is widely, if reluctantly, recognised.

There have been at least two internal evaluations of the UK Government’s flagship Prevent programme — the Channel Project — which tasks public sector workers to detect signs of potential extremism in schools, hospitals, local authorities, universities, and other forums. Under Channel, referrals to the police of individuals who appear to be ‘vulnerable’ to radicalisation results in an assessment process, and an ensuing social intervention of some sort to prevent radicalisation.

Unfortunately, the government’s formal evaluations of Channel have not been published. But in 2010, internal Home Office slides admitted:

“… hard evidence of intervention projects capability [was] not yet established.”

That year, I’d been invited by a senior police officer in charge of the Channel Project to an internal exercise, to see how the programme worked, and to provide advice on its implementation. One of the problems that stood out, and that I’d highlighted in previous conversations with the officer, is that the model of ‘vulnerability’ to radicalisation was so vague as to potentially encompass most normal people.

‘Risk indicators’ included amorphous generalities like, sudden changes in behaviour — for instance, the way you dress or appear, an interest in politics or foreign affairs, a sudden interest in religion, or activism, or even a shift in a person’s friend circle. Basically, most teenagers.

A senior Home Office counter-terrorism official at the exercise with responsibility for managing the national Prevent strategy told me that the vast majority of referrals to Channel would, after being assessed, be dismissed as not requiring any intervention.

“In fact, we see this as a success of the programme,” he said enthusiastically. “The more referrals that come in and are dismissed, the greater the success.”

I looked at him skeptically.

“What you’re saying is that millions of pounds of taxpayers money will be spent on training, organising and assessing pointless referrals of endless numbers of perfectly innocent people who are not at risk of radicalisation,” I said.

The Home Office official nodded, still trying to look enthusiastic.

“Meanwhile,” I continued, “people who are actually developing a real interest in violent extremist ideologies, or even planning terrorist activity, are going to adapt very quickly and do everything they can to avoid being referred.”

The official, and his colleagues who were present, were all genuinely perplexed, but the visage of enthusiasm had now been replaced by the sort of strained look of someone who needs to fart really badly but is trying not to let it out loudly.

“Okay, but what else are we supposed to do?” was what the Home Office official eventually told me in exasperation after we discussed this obvious conundrum.

That was six years ago. Sadly, no one at Channel seems to have taken my advice.

A parliamentary inquiry into both Prevent and Channel by the Select Committee for Communities and Local Government did draw extensively on my criticisms as part of its 2010 report, but the Tory-led government simply ignored most of its recommendations.

The lack of evidence that Channel could ever do more than alienate the very communities that need to be engaged applies to the UK Prevent programme more generally.

“It remains exceedingly difficult to gauge the real success of Prevent,” concluded a 2015 study in the Journalism of Terrorism Research, published by St. Andrews University’s Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence. The paper went on to admit that:

“… very few effective tools aside from anecdotal evidence exist to measure one’s vulnerability to becoming involved in extremism and the effect certain programs may have at reversing such processes… it is unclear as to whether such programmes have actually been successful in deterring extremist ideology.”

Reinforcing Violent Extremism (RVE)

But it’s not just the UK Prevent programme — the entire CVE field is a confused and somewhat redundant mess.

Eight years ago, a team of criminologists at George Mason University systematically reviewed global counter-terrorism strategies. To describe their findings as ‘dire’ would be a disservice to the gravity of their analysis:

“Overall, we found an almost complete absence of evaluation research on counter-terrorism strategies and conclude that counter-terrorism policy is not evidence-based… there is an almost complete absence of evaluation research on counter-terrorism strategies. This is startling given the enormous increases in the development and use of counter-terrorism programs, as well as spending on counter-terrorism activity.”

The few evaluations that did exist either proved that prevailing counter-terrorism strategies didn’t work, or that they were worsening the risk of radicalisation:

“Even more disconcerting was the nature of the evaluations we did find; some programs were shown to either have no discernible effect on terrorism or lead to increases in terrorism…There has been a proliferation of counter-terrorism programs and policies as well as massive increases in expenditures toward combating terrorism. Yet, we know almost nothing about the effectiveness of any of these programs or continue to use programs that we know are ineffective or harmful.”

Yet there has been little, if any, progress since then. In 2014, Steven Heydemann, Vice President of Applied Research on Conflict at the US government-funded United States Institute for Peace, offered the following scathing evaluation of the CVE sector. Despite rapid growth, he wrote:

“CVE has struggled to establish a clear and compelling definition as a field; has evolved into a catch-all category that lacks precision and focus; reflects problematic assumptions about the conditions that promote violent extremism; and has not been able to draw clear boundaries that distinguish CVE programmes from those of other, well-established fields, such as development and poverty alleviation, governance and democratisation, and education.”

One of the most comprehensive reviews of the state of the research on countering extremism was undertaken last year by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) at the University of Maryland. The review was commissioned by the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the US Department of Defense’s (DoD) Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) office, and the resulting document reported straight back to those departments.

The report’s findings are disturbing.

“Most literature addressing counter‐terrorism, counter‐insurgency, and/or countering violent extremism does not include empirical evaluations of specific policies,” it concluded.

“While multiple authors hypothesise that countering extremist narratives is critical to reduce the appeal of violent extremism, there has been very little scholarship in terms of empirical studies to test the efficacy of counter‐narratives in general or of specific strategic communication programs or content.”

As if to hammer this message home, the START report added that there is a serious “shortage of empirical analyses of counter‐terrorism, counter‐insurgency, and CVE policies and programs.” And generally, “within the literature as a whole, there is a shortage of rigorously designed empirical analyses.”

One of START’s flagship projects is the Influencing Violent Extremist Organisations (I-VEO) Knowledge Matrix, an online tool for counter-terrorism practitioners which “identifies and gauges the level of empirical support for more than 180 hypotheses about influencing VEOs [Violent Extremist Organisations], from positive incentives to punitive actions.”

Founded in 2012, I-VEO’s lead investigator, Gary Ackerman, described it as “explicitly designed to be a one-stop shop for capturing and synthesising the breadth of existing scientific knowledge related to influencing VEOs and to highlight those areas where, despite often vigorous assertion, the empirical evidence is lacking.”

Unfortunately, three years later, this US government-funded project showed that most CVE approaches completely lack evidential support.

“As previously found under the I‐VEO effort, many hypotheses regarding influence operations have either not been empirically tested or have been supported merely through anecdotes,” concluded the 2015 START literature review. “This is especially true regarding non‐coercive strategies.”

Amazingly, out of the 183 counter-terrorism methodologies explored in the database, 50 “did not have any relevant empirical evidence to support or contradict” them, while “fifty-seven of the hypotheses had multiple qualitative and/or quantitative studies with contradictory conclusions.”

In the end, there were only sixcounter-terrorism hypotheses that received “the highest level of empirical support.”

So utterly crap, in other words, is the state of the scientific literature on countering extremism, that policymakers have been left floundering — which is perhaps why they are quite literally making shit up as they go along. In the understated words of the START report to the DoD and DHS:

“The state of play in the academic literature regarding counter‐terrorism, counter‐insurgency, and countering violent extremism creates difficulties for providing robust guidance to policymakers regarding policy options.”

Translation: basically, most of our “findings” consist of unsubstantiated bullshit, so it’s difficult to give governments decent counter-extremism advice which isn’t, well, unsubstantiated bullshit.

The few empirically robust findings that can be extracted from the available data, however, raises serious questions about the direction of prevailing PVE/CVE approaches — and whether they might actually be making things worse.

“A majority of studies with evaluation find that use of coercive methods such as repression (especially when used exclusively and indiscriminately) tend to produce backlash effects,” noted the START report to the Pentagon. “Indiscriminate” repression in particular is “unlikely to work in the long‐term and may produce backlash effects that result in more, rather than less, political violence.”

No shit, Sherlock.

The report also found that the practice known as ‘target hardening’ — visibly strengthening the security of a building or infrastructure to prevent or reduce the risk of a successful attack — “may make attacks on those targets less likely”, but may also “result in violent extremists shifting their targeting strategy rather than reducing their overall level of violence.”

In other words, more intrusive security measures like increasing anti-terror powers, flooding the streets with more cops, and trying to monitor everyone will only lead terrorists to adapt, by innovating new techniques to avoid detection.

How not to make friends and influence extremists

It comes as no surprise, then, that in his report, UN Special Rapporteur on Counter Terrorism, Ben Emmerson, documents how PVE/CVE strategies have so far disproportionately targeted and alienated Muslim communities.

Criticising “the elasticity of the term ‘violent extremism’, and the lack of clarity on what leads individuals to embrace violent extremism”, Emmerson concluded that as a consequence, “a wide array of legislative, administrative and policy measures are pursued, which can have a serious negative impact on manifold human rights. In addition, targeted measures to counter violent extremism can stigmatise groups and communities, undermining the support that governments need to successfully implement their programmes, and having a counter-productive effect. They can also be used to limit the space in which civil society operates, and may have a discriminatory impact on women and children.”

This has in some cases served to exacerbate “conditions conducive” to terrorism or violent extremism, including “prolonged unresolved conflicts, dehumanisation of victims of terrorism, lack of rule of law and violations of human rights, ethnic, national and religious discrimination, political exclusion, socio-economic marginalisation and lack of good governance.”

The other empirically robust findings of START’s I-VEO Knowledge Matrix are worth noting. One is that: “If the adversary sees that there are no benefits to restraint, it will work against the deterring party.”

Another is that where there are “multiple” violent extremist organisations, negotiating with just one of them is unlikely to work, as it “may lead to increased bad behavior by VEOs left out of negotiations.”

In other words, there should be obvious incentives to ceasing violence, and those incentives should be offered to all the relevant groups, rather than attempting to play off different groups against each other — which is likely to escalate, not ameliorate, extremism.

Perhaps most significantly, the START database also found abundant empirical evidence that:

“On the whole, positive inducements seem more effective than negative ones in deradicalizing/disengaging.”

The very concept underlying prevailing PVE/CVE approaches, then, is deeply questionable. And finally:

“Political reforms can lower VEO activity.”

This, of course, ties into the issue of developing tangible “benefits” in return for the reduction of violence, and addressing deeper causal factors by inculcating social and political reform.

Other empirical studies provide further grounds for recognising that the current PVE/CVE trend is going nowhere, fast.

One New York University study of terrorist attacks between 1980 and 2008 across 56 countries found that high levels of unemployment correlated significantly with increased instances of terrorism, especially in countries which had already experienced previous terrorist attacks.

A University of Texas empirical analysis of 2448 suicide terrorist incidents from 1998 to 2010 found that “foreign occupation and government transition are greatly associated with suicide terrorist attacks.”

The researchers also concluded that government social services were an important alleviator of transnational suicide attacks, but that “military spending is not effective at curbing transnational suicide terrorism,” raising questions about providing foreign counter-terrorism assistance “to countries beset with such attacks.”

In 2011, a study by the London School of Economics and University of Essex, published in the Journal of Peace Research, examined terrorist attacks on Americans by foreigners between 1978 and 2005.

Their model showed that US military support to foreign governments had “substantively strong effects on foreign terror on Americans.” A significant rise in military aid, for instance, produced an increase in anti-American terrorism by 135%.

The new Government Actions in Terrorist Environments (GATE) dataset provides further insights. A preliminary University of South Carolina study found that with regard to Palestinian terrorism, “when significant, [Israeli] repression is associated with more [Palestinian] terrorism (backlash) and conciliation is associated with less terrorism. This finding is especially strong when the actions are indiscriminate and during the Second Intifada.”

Similar conclusions applied for the wider region:

“For the remaining Middle Eastern countries, repression is either ineffective, or associated with more terrorism; and conciliation is either ineffective or associated with less terrorism.”

Likewise, in Canada, “al-Qaeda inspired extremism was very sensitive to actions by the Canadian Military in Afghanistan.”

Last year, a paper in the Journal of Deradicalization published by the Modern Security Consulting Group in Berlin, examined the evidence of causation between different types of military intervention, and the radicalisation process, including the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the US-led drone programme, and coalition strikes against ISIS. The paper, noting that this issue has been largely overlooked in the wider terrorism literature, found that:

“… intervention by a foreign power can encourage the process of radicalisation, or ‘de-pluralisation’ — the developing perception that there exists only one solution, extreme violence — to take place. However, it finds that the type of intervention plays a critical role in determining how individuals experience this process of depluralisation; full-scale intervention can result in a lack of monitoring alongside frustrations (about lost sovereignty for example), a combination which paves the way for radical ideology. Conversely, airstrikes present those underneath with unequal and unassailable power that cannot be fairly fought, fuelling interest in exporting terrorism back to the intervening countries.”

The critical role of state repression, then, is absolutely clear from the available data — but has had little tangible impact on the narcissistic echo chamber of state counter-terrorism strategies.

The state we’re in, but ignore

This suggests that much of what passes for ‘research’ in terrorism studies on the intricacies of the radicalisation process is fundamentally misguided.

Pinpointing multiple pathways to violent radicalisation, numerous overlapping risk-factors and complex interlinked causes has borne little fruit, because the whole enterprise is premised on the assumption that the focal point of analysis should be an internal, psychological change applying to an individual.

As a result, the wider historical, social, cultural, economic, political and ideological context of the radicalisation process has been neglected.

The failure of terrorism studies is not simply a matter of lack of data, but down to the bankruptcy of its very foundational assumptions, the very framing of the problem, and the questionable political and ideological context of that framing: state counter-terrorism policies.

And this brings us back to the central question of empirical analysis. To what extent have self-styled ‘terrorism experts’ really engaged with the empirical reality of terrorism?

The answer is not at all: because the vast bulk of terrorism studies is obsessed exclusively with the radicalisation of individuals, and networks of individuals. But the biggest perpetrators of terrorism, defined as political violence against civilians, are states themselves.

The problem is that primary sources of empirical data on terrorist incidents are either governments themselves, or government-sponsored think tanks and academic groups — which means that they systematically exclude data on terrorist incidents perpetrated by those governments.

A University of Illinois study by political scientist Gregory Holyk — a senior researcher for ABC News’s leading public poll provider Langers Research Associates — compared the lethality of US state terrorism and non-state terrorism between 1968 and 1978. The study found that “the mean number of people killed in state-sponsored terrorist events was significantly greater than the mean number killed in non-state terrorist events,” and cast doubt on the “focus on non-state terrorism in the literature.”

In her seminal 2009 Routledge study, State Terrorism and Neoliberalism: The North in the South, Professor Ruth Blakeley, Head of the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Kent, provided a further wealth of evidence on the vast extent to which Western states perpetrated terrorism during and after the Cold War. The death toll of this continuum of terror far outweighs the scale of atrocities by al-Qaeda and ISIS.

Even less palatable is the ongoing role of Western states in allying with other state-sponsors of Islamist terrorism, such as Pakistan, the Gulf states and Turkey — all of which have been implicated by credible primary source data in deliberately supporting extremist terrorist groups — for geopolitical purposes.

The emerging sub-field of ‘critical terrorism studies’, pioneered by the likes of Blakeley and others, is beginning to subject conventional academic discourses on terrorism to critical scrutiny. Researchers are opening up new historical, sociological and empirical approaches to understanding both non-state and state-terrorism.

Unfortunately, there’s still a long way to go before this research is able to do more than shine a somewhat unsavoury light on the mountains of shameless bullshit that has accumulated over the last few decades.