Everyone’s talking about Brexit. Some about the French riots. But no one’s talking about why they are happening, and what they really mean. They might think they are, but they are usually missing the point.

On 6th May 2010, the Conservative Party took the reins of power for the first time since 1992, propped up with some help from the Liberal Democrats. Hours before the election result, I warned in a blog post that whichever government was elected, it would be the first step in a dramatic shift toward the far-right that would likely sweep across the Western world within 10 years.

“The new government, beholden to conventional wisdom, will be unable or unwilling to get to grips with the root structural causes of the current convergence of crises facing this country, and the world,” I wrote, describing the failure of all three political parties to understand why the heyday of economic growth was unlikely to return.

“This suggests that in 5–10 years, the entire mainstream party-political system in this country, and many Western countries, will be completely discredited as crises continue to escalate while mainstream policy solutions serve largely to contribute to them, not ameliorate them. The collapse of the mainstream party-political system across the liberal democratic heartlands could pave the way for the increasing legitimization of far-right politics by the end of this decade…”

My prediction was astonishingly prescient. The global shift to the far-right began within exactly five years of my forecast, and has continued to accelerate before the decade is even out.

In 2014, far-right parties won 172 seats in the European Union elections — just under a quarter of all seats in the European Parliament. In 2015, David Cameron was re-elected as Prime Minister with a parliamentary majority, a victory attributed in part to his promise to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union.

Unbeknownst to many, the Tories had quietly established wide-ranging links with many of the same far-right parties that were now capturing seats in the EU.

The following year in June, the ‘Brexit’ referendum shocked the world with its result: a majority vote to leave the EU.

Six months later, billionaire real estate guru Donald Trump shocked the world again when he became president of the world’s most powerful country. Like the Conservatives in the UK, the Republicans too had forged trans-Atlantic connections with European parties and movements of the extreme-right. Since then, far-right parties have made continued electoral gains across Europe in Italy, Sweden, Germany, France, Poland and Hungary.

We are on the cusp of a tidal wave, that looks poised to accelerate into a tsunami. Exactly as I had anticipated, far-right politics is no longer the province of the fringe, but is becoming increasingly normalised. This not an accident. It is the result of a system that is failing — and the efforts of a network of far-right groups to exploit the fractures emerging from this system-failure to tear everything down, and erect a new order of their own fashioning.

My prediction of the resurgence of the far-right was based on analysing the probable consequences of a long-term ‘system-failure’ in which we are unable to return to the levels of economic growth we had become accustomed to in the heyday of the 1980s and 90s. That system-failure, I explained, is rooted in the economics of the energy production that enables economic growth:

“…. a full and lasting recovery… is likely to be impossible in the constraints of the current system, because we’re running short on the physical basis of the last few decades of exponential (and fluctuating) ‘growth’ — and that is cheap, easily available hydrocarbon energies, primarily oil, gas and coal.

“The turning point has arrived, and without that global cheap energy source in abundant supply, we cannot continue growing, no matter what we do. Something has to give. Our economies need to be fundamentally, structurally, transformed. We need to transition to a new, clean, renewable energy system on which to base our economies. We need to transform the way money is created, so that it’s not linked to the systematic generation of debt. We need to transform our banking system on the same grounds. Whitehall, and the three political parties, recognize only facets of the picture, but they don’t see it as a whole.”

Turning point

The energy turning point is unequivocal. In the years preceding the historic Brexit referendum, and the marked resurgence of nationalist, populist and far-right movements across Europe, the entire continent has faced a quietly brewing energy crisis.

Europe is now a ‘post-peak oil’ continent. Currently, every single major oil producer in Western Europe is in decline. According to data from BP’s 2018 Statistical Review of Energy, Western European oil production peaked between 1996 and 2002. Since then, production had declined while net imports have gradually increased.

In a two-part study published in 2016 and 2017 in the Springer journal, BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, Michael Dittmar, Senior Scientist at the ETH Zurich Institute for Particle Physics and CERN, developed a new empirical model of oil production and consumption.

The study provides perhaps one of the most empirically-robust models of oil production and consumption to date, but its forecast was sobering.

Noting that oil exports from Russia and former Soviet Union countries are set to decline, Dittmar found that Western Europe will find it difficult to replace these lost exports. As a result, “total consumption in Western Europe is predicted to be about 20 percent lower in 2020 than it was in 2015.”

The only region of the world where production will be stable for the next 15 to 20 years is the OPEC Middle East. Everywhere else, concludes Dittmar, production will decline by around 3 to 5 percent a year after 2020. And in some regions, this decline has already started.

Not everyone agrees that a steep decline in Russia’s oil production is imminent. Last year, the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies argued that Russian production could probably continue to grow out to at least 2020. How long it would last thereafter was unclear.

On the other hand, the Russian government’s own energy experts are worried. In September 2018, Russia’s energy minister Alexander Novak warned that Russia’s oil production might peak within three years due to mounting production costs and taxes. In the ensuing two decades, Russia could lose almost half its current capacity. This sobering assessment is still broadly consistent with the Oxford study.

The following month, Dr Kent Moor of the Energy Capital Research Group, who has advised 27 governments around the world including the US and Russia, argued that Russia is scraping the bottom of the barrel in its prize Western Siberia basin.

Moor cited internal Russian Ministry of Energy reports from 2016 warning of a “Western Siberia rapid decline curve amounting to a loss of some 8.5 percent in volume by 2022. Some of this is already underway.” Although Russia is actively pursuing alternative strategies, wrote Moor, these are all “inordinately expensive”, and might produce only temporary results.

It’s not that the oil is running out. The oil is there in abundance — more than enough to fry the planet several times over. The challenge is that we are relying less on cheap crude oil and more on expensive, dirtier and unconventional fossil fuels. Energetically, this stuff is more challenging to get out and less potent after extraction than crude.

The bottom line is that as Europe’s domestic oil supplies slowly dwindle, there is no meaningful strategy to wean ourselves off abject dependence on Russia; the post-carbon transition is consistently too little, too late; and the impact on Europe’s economies — if business-as-usual continues — will continue to unravel the politics of the union.

While very few are talking about Europe’s slow-burn energy crisis, the reality is that as Europe’s own fossil fuel resources are inexorably declining, and as producers continue to face oil price volatility amidst persistently higher costs of production, Europe’s economy will suffer.

In September, I reported exclusively on the findings of an expert report commissioned by the scientific group working on the forthcoming UN’s Sustainability Report.

The report underscored that cheap energy flows are the lifeblood of economic growth: and that as we shift into an era of declining resource quality, we are likely to continue seeing slow, weak if not declining economic growth.

This is happening at a global scale. EROI is already beginning to approach levels seen in the nineteenth century — demonstrating how constrained global economic growth might be due to declining net energy returns to society.

Britain: the end of net energy growth

Britain, which is due to leave the European Union on 29th March 2019, is a poster boy for this brewing energy-economic crisis.

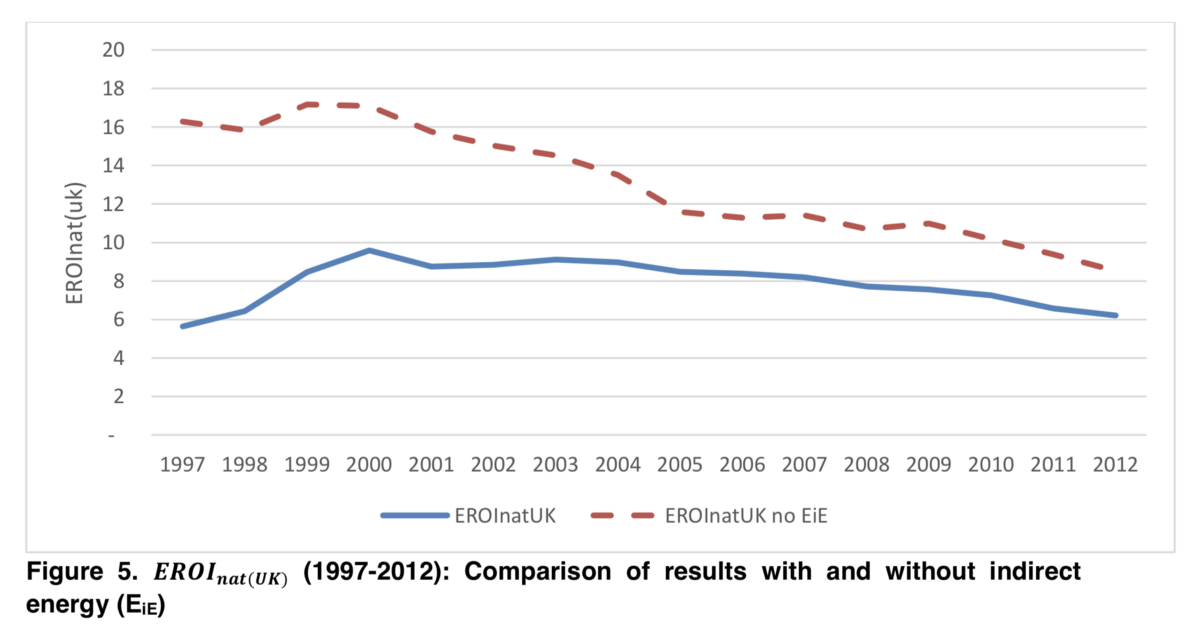

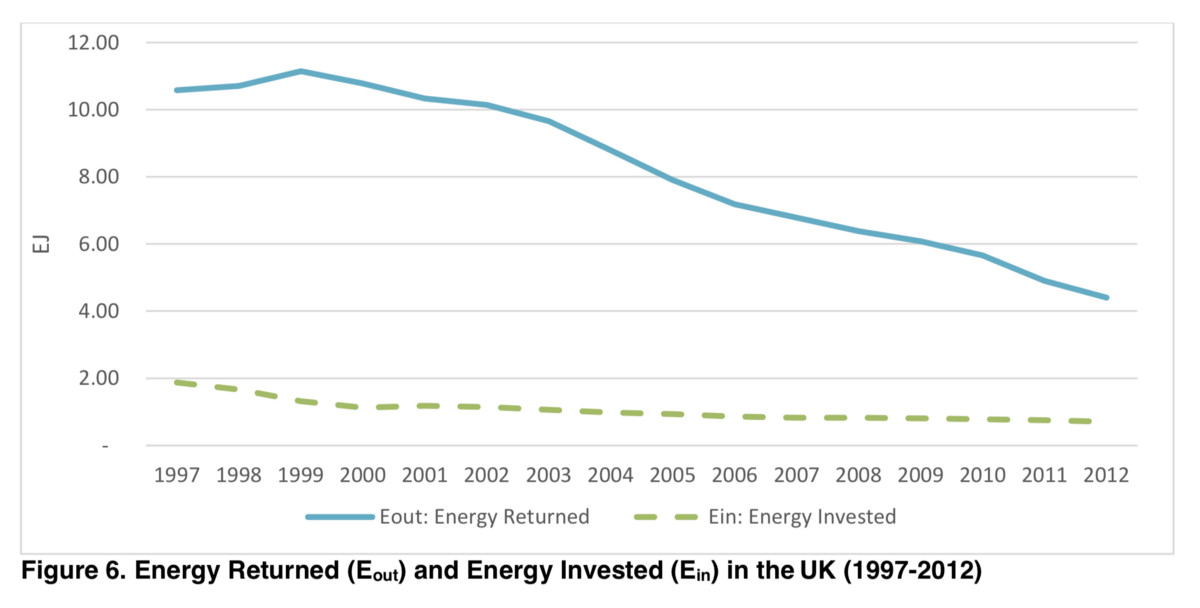

In January 2017, the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy run by the University of Leeds and London School of Economics, produced a startling analysis of Britain’s declining net energy problem. The study attempted to develop a methodology to examine national-level figures for Energy Return on Investment (EROI) — the amount of energy one uses to extract a particular quantity of energy.

The goal of the study was to pinpoint the EROI value as much as possible using Britain as a prime case-study. The concept of EROI fleshes out the recognition that a significant surplus of energy is required to fuel economic activity, separate to energy that is consumed precisely to extract energy in the first place.

The less energy we use to get new energy out, the more energy we have left to invest in the wider goods and services of economic activity. But if we keep using more energy just to get energy out, the amount of net energy we have left to fuel our economies decreases.

According to the study authors, Lina Brand-Correa, Paul Brockway, Claire Carter, Tim Foxon, Anne Owen and Peter Taylor:

“The higher the EROI of an energy supply technology, the more ‘valuable’ it is in terms of producing (economically) useful energy output. In other words, a higher EROI allows for more net energy to be available to the economy, which is valuable in the sense that all economic activity relies on energy use to a greater or lesser extent.”

The verdict on the UK predicament is stark. They find that “the UK as a whole has had a declining EROI in the first decade of the 21st century, going from 9.6 in 2000 to 6.2 in 2012… These initial results show that more and more energy is having to be used in the extraction of energy itself rather than by the UK’s economy or society.”

Citing the work of French economists Florian Fizaine and Vincent Court, which estimates a minimal societal EROI of 11 for continuous economic growth, the paper concludes:

“… the UK is below that benchmark.”

In other words, early last year, a major scientific study found that for the last two decades and beyond, Britain’s economic growth is fundamentally constrained by domestic net energy decline. But this groundbreaking news did not make the ‘news’.

Break-up

At the close of 2010, in my book A User’s Guide to the Crisis of Civilization, I predicted that large trans-national state structures like the European Union are likely to face challenges to their territorial integrity as a side-effect of these processes. The failure to address the systemic causes behind the 2008 financial crash, the incapacity to recognise it as a symptom of a system in decline, would lead to an increasingly authoritarian politics.

The integrity of large trans-national structures depends on the abundance of cheap energy flows to sustain them. If those flows come at greater cost and lower quality, then those structures will become increasingly strained and potentially even begin to break down. Costs to keep the system going increase while returns are squeezed, meaning that the surplus to invest in core social goods to maintain such structures declines.

That is why despite the so-called ‘recovery’ — tepid as it is and based on accelerating debt levels (in biophysical terms borrowing from the Earth today with promise of paying it back tomorrow with what has already been over consumed today) — in real terms, peoples’ purchasing power continues to decline.

The failure to understand and engage with the root, systemic causes of the crisis also means that policymakers put themselves in a position where they can only address surface-symptoms.

All too often, that means short-term, reactionary responses. And so in France, instead of addressing the question of how to galvanise a third industrial revolution to speed a post-carbon transition and infrastructure revival, Macron’s response to the climate crisis was to protect fossil fuel and nuclear producers while hiking up fuel taxes. He didn’t want to tackle the horrendous supply chains of big French corporations. He didn’t want to penalise the powerful oil, gas and nuclear lobbies that he hopes might help him get re-elected, and did next to nothing to speed a viable post-carbon transition that might transform economic prosperity on more sustainable foundations.

And so by placing the burden almost exclusively on French workers and consumers, Macron triggered the spiral of rage and riots. Protestors have set fire to banks, smashed and looted shops, and even targeted the Arc de Triomphe. They demand an end to corporate freeloading, along with nationalist demands such as ‘Frexit’, France’s departure from the EU, and preventing migration. It is telling that while some demands are compelling, there is no semblance of understanding the real planetary crisis beyond banal tropes about Big Banks. The French state has responded with its own violence, firing water cannons and tear gas on protestors, arresting over a thousand people, and threatening to bring in the French Army.

This is a microcosm of what can happen when states and peoples both fail to understand the deeper dynamics of a failing system: everyone responds to what is in front of them. Protestors blame Macron. The French state cracks down on violence. Politics becomes militarised, while scepticism of the liberal incumbency across the political spectrum finds vindication.

France’s riots therefore did not come out of the blue. They are part and parcel of a wider process of slow-burn EROI decline in which the returns to society from economic activity are being increasingly constrained by the higher energetic costs of that activity and productivity declines of the ageing centralised industrial-era infrastructure and technology. It was only a matter of time before the average person began to feel the impact of that squeeze in their day to day lives. Macron’s tax hikes were not the cause, but the trigger. They lit the match, but the tinder box was already fuming.

Brexit

But we’ve been here before, in Syria and beyond.

Brexit was triggered in the context of global system dynamics which remain poorly understood. Over the decade preceding the 2008 financial crisis, Britain’s economic growth was being undermined not merely by a debt-bubble in the housing markets, but by an ailing fossil fuel dependent energy system.

That ailing system was indelibly linked to the European migrant crisis, which saw over a million refugees from the Middle East and North Africa seeking sanctuary across Europe, including the UK and France, that fuelled the surge in nationalist populism sweeping across the continent.

The migrant crisis, too, did not come out of the blue, but followed hot on the heels of the turbulence of the Arab Spring. The destabilisation of Syria, Egypt, Yemen and beyond was a long time coming — but it was triggered by a perfect storm of crises. Domestic oil production declines which pulled the rug out from beneath oil-export dependent state revenues conspired with global oil price spikes thanks to the plateauing in world production of cheap conventional oil. A string of climate crises across the world’s major food basket regions led to crop failures and droughts which boosted food price spikes.

Global systemic crisis interacted with the breakdown in local national systems. As I’d reported in 2013, a natural drought cycle in Syria was massively worsened due to climate change, devastating agriculture and driving hundreds of thousands of Sunni farmers into Alawite-dominated coastal cities. As Syrian oil revenues plummeted, its domestic conventional oil production having peaked in the mid-1990s, the government’s slashing of critical fuel and food subsidies just as prices were spiking globally was the last straw. People could not even afford bread, so they hit the streets.

Bashar al-Assad responded with escalating brutality, including shooting civilians in the streets. When protestors picked up arms in response, the cycle of violence kicked in. Outside powers intervened to coopt their favoured sides, Russia and Iran backing Assad, the West backing various rebel groups — neither particularly interested in supporting Syrian civil society. The conflict escalated, devastating the country, and fuelling an unprecedented refugee crisis.

When NATO intervened in Libya, when the US and UK backed Saudi Arabia’s indiscriminate aerial bombardment of Yemen, it only destabilised the region further. The arc of collapse across the Middle East and North Africa resulted from a fatal combination: an earth system crisis, compounded by short-sighted and self-serving responses from human systems.

When families and children began turning up in their droves on European shores, the earth system crisis ‘out there’ came home. The West could not shield itself from the long-range consequences of the unsustainability of the very postwar system it had nurtured since the Second World War: structural dependence on fossil fuels, a patchwork of alliances with regional despotic regimes, laying the groundwork for converging climate change, crude oil depletion and the resulting domino effect of food and economic crises.

The earth system crisis that erupted in Syria triggered a wave of human system destabilisation of which Brexit was merely the first eruption.

And so the Syria crisis is indeed a taste of things to come. Europe is already a post-peak oil continent, whose domestic fossil resources are in decline. Most credible studies of Europe’s shale gas potential show that it is extremely weak and not similar to the American situation. If we are hell-bent on maintaining dependence on fossil fuels, we will be forced to import.

But as I showed in my scientific monograph for Springer Energy Briefs, Failing States, Collapsing Systems: BioPhysical Triggers of Political Violence (2017), if demand growth increases at current rates, it is unlikely that Central Asian and Russian suppliers will be capable of meeting that demand at costs we can cope with in coming decades.

Meanwhile, certain climate impacts are already locked in. Between 2030 and 2045, large parts of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are likely to become increasingly uninhabitable due to climate change. This is the same period in which oil production across the MENA region has been forecast to begin plateauing and declining. As the energy costs of fossil fuel production and imports increases, and as the EU is likely hit again by the challenge of large-scale migration from the Middle East due to climate devastation, the challenges to the EU’s territorial integrity will not go away.

Brexit is merely a ripple on the surface of deeper currents. It is a symptom of the great civilisational phase-shift to life after fossil fuels.

In this sense, the Brexit fiasco is an example of how distant we are as a species from the conversations we need to be having. Talking about being in or out of Europe and in what way is not unimportant, but it’s also a massive distraction from the deeper systemic crisis that is unfolding beneath the very issues driving our immediate concerns about Brexit.

Earth system disruption does not inevitably result in destabilisation of human systems. But if human systems refuse to engage and adapt to those disruptions, then they will be destabilised. As long as Britain, Europe and their citizens continue to obsess myopically on the symptoms rather than the causes, we will be incapable of responding meaningfully to those causes. Instead, we will fight with each other manically about the symptoms, while the ground beneath our feet continues to unravel.

The crisis of Brexit and the eruption of the riots in France are symptoms of a great unfolding civilizational transition, in which an old reductionist paradigm of materialist self-maximation is dying. Citizens and policymakers, activists and business leaders, need to wake up to what is actually happening to have the conversations that can kick-start meaningful approaches to systemic transformation.

This is not a far-flung crisis that is going to happen years in the future. This is now. This is happening and it is affecting you, your children, and those you love the most. And it will affect their children, and their children.

This is your legacy. This is your choice. This is your chance to engage with and become an agent of a new paradigm, one that speaks for all humans, all species, and the Earth itself. Maybe we don’t know exactly what the emerging paradigms will look like. But we know that it’s time to ask ourselves: where do we stand? With the old, or with the new?