The prevailing opinion among today’s political and economic elites is that economic globalisation is in some sense inevitable, perhaps even the summit of human achievement. The oft-repeated mantra is that ‘there is no alternative’ and we should adapt to it as best we can.

Rather than being inevitable, economic globalisation is, in fact, the result of a number of carefully chosen policies. Paradoxically, as we shall see, many of these directly contradict the basic tenets of classical free market economic theory, from which the proponents of economic globalisation draw much of their inspiration and authority.

By understanding the key reasons why the global economy behaves as it does today, we will be in a better position to discern the core patterns underlying economic behaviour and, if we choose, to change them. Two key drivers of today’s global economy are externalities and subsidies.

These two factors heavily skew market prices in favour of large-scale industrial goods and services and against small-scale and locally-based economies. These two drivers are further reinforced by the type of money systems that are dominant in today’s global economy that create a structurally dysfunctional growth imperative and wealth disparities with devastating impacts on health, social cohesion, as well as, national and international security. Kenny Ausubel, co-founder of Bioneers, has put it succinctly:

“The world is suffering from the perverse incentives of ‘unnatural capitalism’. When people say ‘free market’, I ask if free is a verb. We don’t have a free market, but a highly managed and often monopolized market. …we have banks and companies that are ‘too big to fail,’ but in truth are too big not to fail. The resulting extremes of concentration of wealth and political power are very bad for business and the economy (not to mention the environment, human rights, and democracy). One result is that small companies can’t advance too far against the big players with their legions of lawyers and Capitol Hill lobbyists, when in truth it’s small and medium-sized companies that provide the majority of jobs as well as innovation.”

Kenny Ausubel (in Harman 2013: 77)

The current, far from free, market system has permitted a progressively greater concentration of economic power in ever fewer hands in a way completely at odds with the vision held by the founding figures of classical economics, such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who imagined a free and competitive market occupied by a healthy diversity of predominantly small-scale producers serving largely local markets.

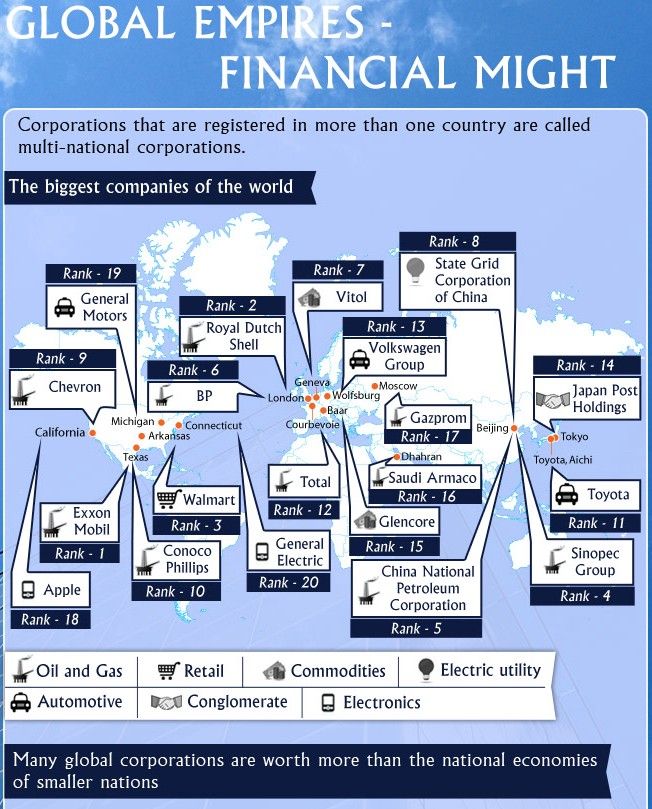

The global economy has come to be dominated by a relatively small number of vast corporations: today, 37 of the world’s 100 largest economies are corporations (Transnational Institute, 2014). The Transnational Institute, the International Forum on Globalization, and the Centre for Research on Globalization are three independent NGOs offering constant up-dates on the dangerous power imbalances in our globalized economy.

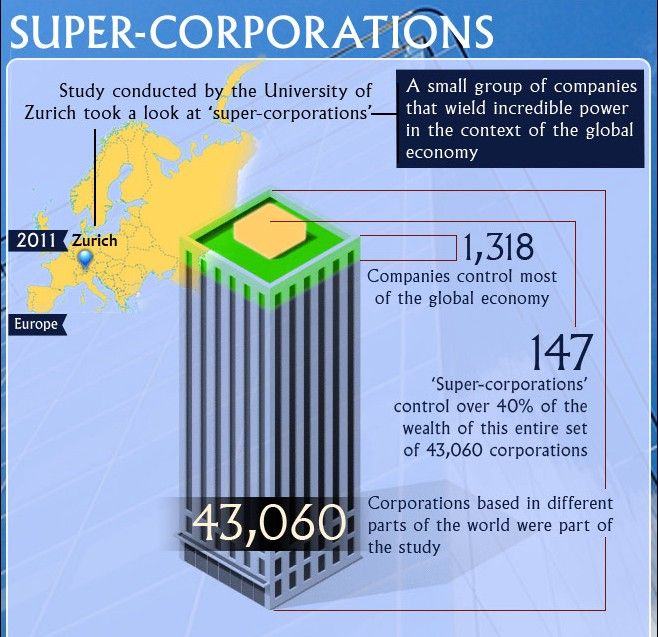

A 2011 study by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology analysed the network connections between 43,000 trans-national corporations and found that a relatively small number of them (147 corporations) form a highly-connected “super-entity” that controls almost 40% of the total wealth in the network (Coghlan & MacKenzie, 2011).

Multinational corporations not only rank amongst the planet’s biggest economies, their political lobbyists are affecting national and international policies in ways that make democratically elected governments of sovereign states respond to their bidding due to the huge economic power these corporations hold.

Externalities: privatizing the wins and socializing economic, environmental and social costs

‘Americans import Danish sugar cookies, and Danes import American sugar cookies. Exchanging recipes would surely be more efficient.’

— Herman Daly

Externalities is the term given to the many social and environmental costs that are not included in the price paid by the consumer of industrially-produced goods and services. Externalities occur when there are costs (or benefits) to anyone not in control of the transactions or decision-making process. Here is a short video (4 min.) explaining the disastrous impacts externalities can have.

Were externalities to be internalised — that is, were the true social and ecological costs associated with industrial products to be included in the price charged to the consumer — there would be a sharp increase in the costs of these products.

It is important to understand that “cheaper” products ar not actually cheaper, as we all end up paying indirectly for the social, environmental, and health costs associated with unsustainable patterns of production.

What we need is true cost accounting, also called environmental full cost accounting. Here is a short video (3 min.) created by the Lexicon of Sustainability explaining this approach using the example of food production.

Subsidies often incentivise degenerative activity

Large-scale industrial systems benefit from truly enormous subsidies of various kinds. It has been estimated that every year, the world’s tax-payers provide an estimated $700 billion of subsidies for environmentally destructive activities, such as fossil fuel burning, overpumping aquifers, clear-cutting forests and over-fishing (Brown 2008).

These include direct payments to industries that governments seek to protect. One sector in which such subsidies are common practice is agriculture, with governments in the industrialised world providing huge subsidies to their farmers. Other sectors that are supported by huge — and often hidden — subsidies are the fossil fuel and the nuclear industry,

‘There is something unbelievable about the world spending hundreds of billions of dollars annually to subsidise its own destruction’

— Subsidising Unsustainable Development, The Earth Council

Farm subsidies in the economically rich countries of the North have been estimated at $300b per annum, with the great majority going to the largest-scale farmers: some 78% of US agric subsidies (around $17 billion per annum), for example, go to the largest ten per cent of farmers. Subsidies to 250,000 US cotton farmers alone are greater than all US official aid to Africa, with a population 800 million (Norberg-Hodge 2003).

The removal of agricultural subsidies is consistently at the top of the agenda of the countries of the global South in international trade negotiations under the aegis of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), since their farmers simply cannot compete with the heavily subsidised products generated by Europe and the US. For example, EU subsidies encourage an annual surplus of six million tonnes of sugar, much of which is dumped in the markets of poor countries at below production prices (more information).

Large corporations also receive various other forms of indirect subsidies offered by national governments. These include:

- government research grants to universities and think-tanks whose research agendas are increasingly driven by corporate interests

- tax breaks and other incentives by national and local authorities to encourage large business to locate in their territory

- expenditure on transport infrastructure (roads, airports, ports) that is paid for by tax-payers but used disproportionately by the distributors of industrial products

- governments underwriting the loans of large industries

- investment in education systems that are geared to supply trained workers for large industries

- manipulating currency exchange rates in the global market to favour conditions for export

- the absence of a tax on aviation fuel.

“The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy is responsible for 85% of the world’s agricultural export subsidies, which may well qualify as the largest distortion of any sort of trade”

— Charlene Barshefsky, US trade representative

Part of the problem here is the progressively greater intertwining we have seen in recent years between government and business. In many countries, corporations fund the political process, in some cases providing finance to all political parties that are likely winners of elections. Individuals move easily between government and senior positions in business and many policy committees in parliaments all over the world are dominated by corporate interests. This makes it difficult either to remove perverse subsidies or to orient policies in a more ecologically- and community-friendly direction.

Even the International Monetary Fund has woken up to the disastrous environmental and social impacts of the vast subsidies that are currently supporting the fossil fuel industry. A 2015 IMF report estimates post-tax global energy subsidies to amount to 5.3 trillion $US in 2015, and concludes “environmental damage from energy subsidies are large and energy subsidy reform through efficient energy pricing is urgently needed” (IMF, 2015).

The Guardian (2015) has highlighted that these vast subsidies correspond to $US 10 million per minute supporting the fossil fuel industry. The newspaper supports the international campaign calling for ‘fossil fuel divestment’ which has been joined by large institutions like the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and has already reached a cumulative commitment of $US 2.3 trillion to divest away from fossil fuels (Gofossilfree, 2015).

The Guardian also helped to promote 350.org and Bill McKibben’s ‘Do the Math’ campaign arguing that we cannot burn most of the current fossil fuel reserves if we want to avoid run-away climate change and stay well below and average global warming of below 1.5ºC. Here is a video (11:30 min.) explaining why we need to keep most of the remaining fossil fuel reserves in the ground and make the shift to renewable energy sources as quickly as possible.

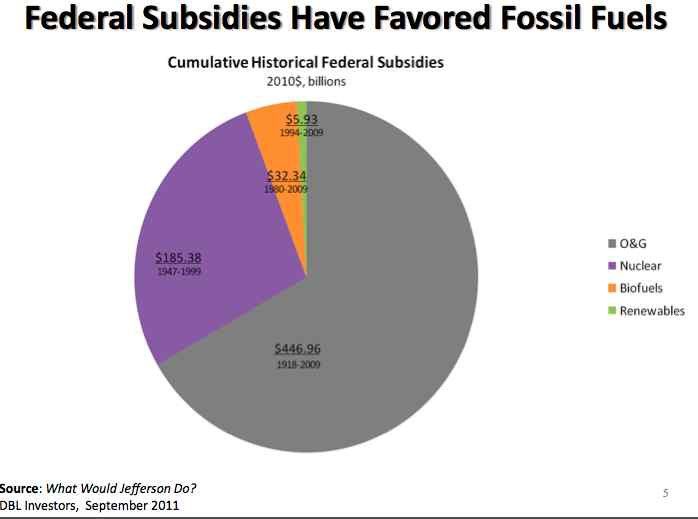

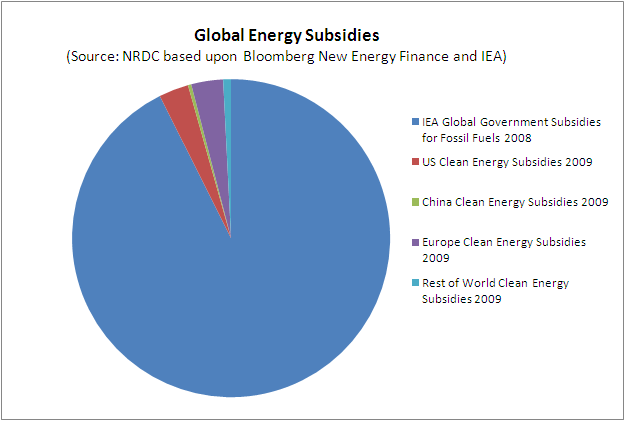

The Union of Concerned Scientists in the USA published a report in 2011 demonstrating that nuclear energy had never been and is still not viable without vast government subsidies. (UCSUSA, 2011). While governments around the world spend vast amounts of money to subsidize the fossil and the nuclear fuel industries, the subsidies that flow into the support of renewable energy are by comparison very small and are often the first subsidies to be cut in an economic downturn. The graph below shows this mismatch.

Other examples of ‘perverse subsidies’ include vast payments to keep fishermen in jobs and catches high while most of the world’s fisheries are close to collapse (Cowe, 2012a). Subsidies to large international water companies are keeping water prices artificially low and exacerbate the already excessive over-pumping of the world’s aquifers and use of fresh water (Cowe, 2012b).

For more detailed information on different types of subsidies and their effects you can take a look at the Subsidy Primer by Ronald Steenblik of the International Institute for Sustainable Development, who is a contributor to the Global Subsidies Initiative aiming encourage individual governments to act on unilateral reform of subsidies to deliver clear social, environmental and economic benefits.

The existing systemic structures around subsidies to industries with a severely degenerative impact on people and planet, along with the existing economic practice of externalising the devastating social, ecological, and economic impacts of these industries and their globalized system are critical stumbling blocks on the way towards regenerative economies. Without addressing these issues and the fact that many of the largest corporations in the world are too big not to fail, it will be very difficult to create the vibrant bioregional economies that would drive widespread regeneration while serving diverse regenerative cultures and their thriving communities.

NOTE: this article is adapted from an abridged excerpt of the ‘Economic Design Dimension’ of Gaia Education’s online course in ‘Design for Sustainability’ which I wrote in 2015.