From a certain perspective, the great gift to be gleaned from the latest presidential race and subsequent election is to become very clear that this experiment in democracy unique to the United States and other western societies is in fact just that, an experiment.

The founding fathers of America were irrevocably influenced by Enlightenment values, particularly the principles of egalitarianism and rationality. They crafted this crazy experiment called democracy out of these principles, and over the last few centuries a whole host of elements have been added to the core axioms set forth in the Declaration of Independence and were then codified in the Constitution.

The history and agendas, however, behind the founding of America are not quite as romantic as some might think. Many times throughout the history of the United States it becomes apparent— much like we are seeing now — that the departure from monarchy has not directly translated into the adopted notions of civil freedom, or voting rights, or racial and gender equality.

As John Randolph of Roanoke once said: “I love liberty. I hate equality.”

Whereas in other eras this fact shows up as obvious — the massacre of native peoples, the enslavement of Africans, refusing women the vote, segregation and massive race inequality — in the present era the picture is not so clear. Yes, we can point to serious issues around wealth concentration, unchecked corporate power, inner-city poverty, and police brutality to name but a few.

But the real issue at the center of any viable democracy is choice; the ability to choose leadership and influence policy in a way that supports society and human beings at their very best.

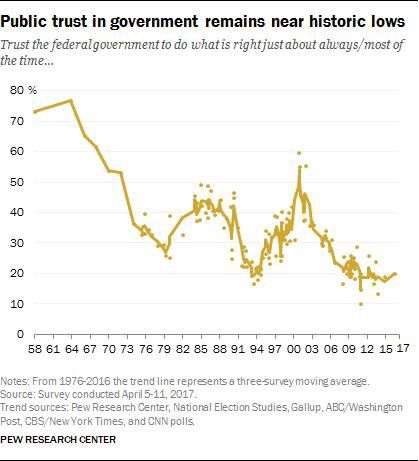

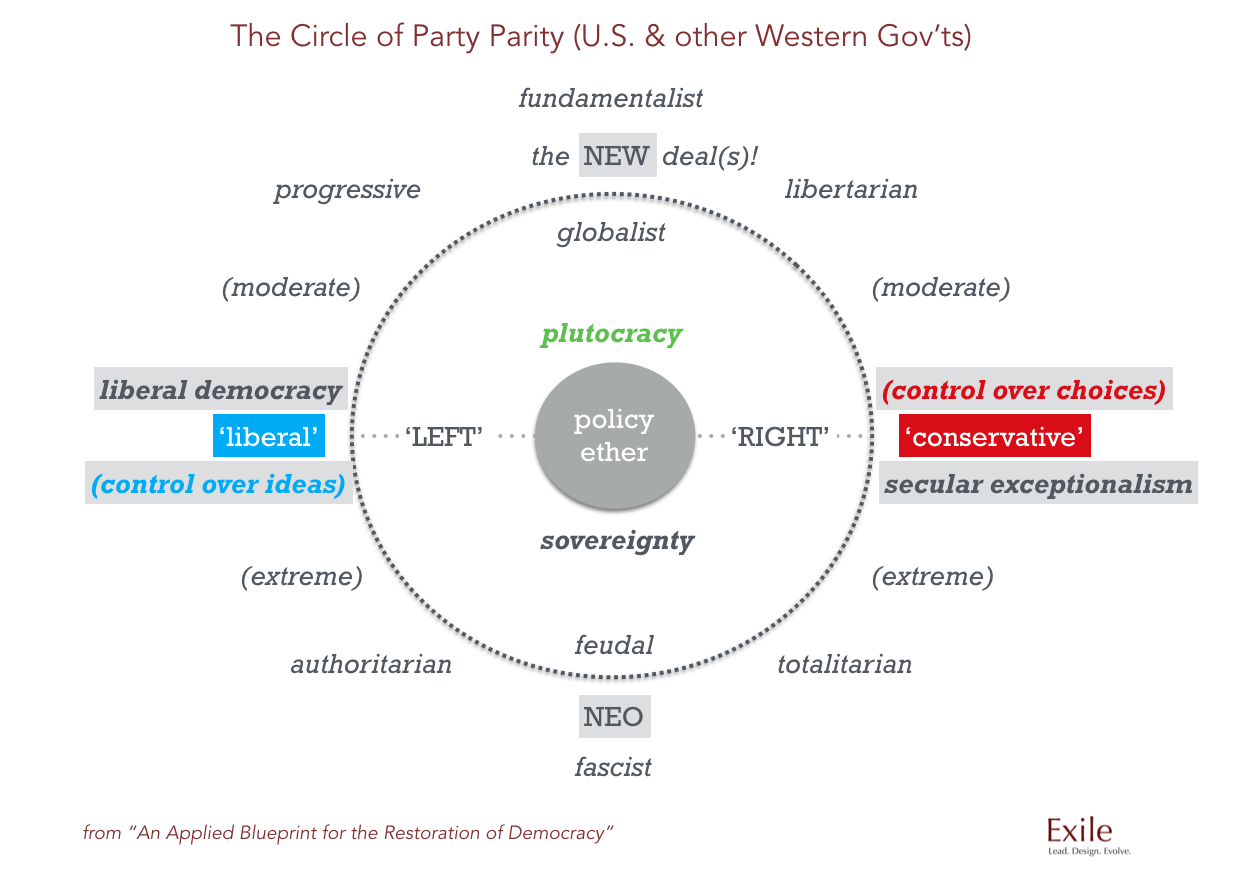

This election cycle, perhaps more than any before, helps us to see how representative choice and the power of an informed electorate live on as ideals but have very little relationship to reality. We created this graphic to illustrate a situation that millions of citizens sense; the current democratic system provides little more than the illusion of choice. As a voter, one can cast a vote in favor of a party in service to the control over ideas, or cast a vote in favor of a party in service to the control over choices.

This barren democratic landscape, of course, can easily seduce us into a state of apathy and resignation. But, if we keep in mind that democracy is an experiment of history, and we are creators of history, we know that something can be done.

The fundamental mistake, however, that people make when examining what is “wrong” with the system is to try and change, modify or improve upon it. Such a move is a grave error, and not in keeping with the energy and daring nature of the original founders. Further, it is actually pointless when you realize — per the graphic above — that party parity reveals a single, non-adaptive system.

Instead, the move today is to prototype an evolutionary step-change that does not try to correct anything. Looked at from the perspective of an evolutionary process, what we see is the experiment in American Democracy going through a necessary period of creative collapse.

One way to understand what is going on today is to look at what happened to science, particularly the realm of physics, in the middle of this last century. Scientists then were confronted with the collapse of the most basic and rudimentary laws of science, laws that had stood for centuries. In the face of new data and new perspectives leading scientists faced a choice: Ram the new data and perspectives into the old laws because the laws were sacrament, or let the new dissolve the solidity of the old. They chose the latter.

We are forced to make the same choice today when considering what our responsibilities are as citizens to this grand system of democracy. We can stubbornly hold on to the old laws that govern a liberal democracy, or we can create new ones that will support a true civic engagement model for democracy.

We are certain that in every measure, a civic engagement model is more coherent and closely aligned to this moment in history. In this writing we will lay it all out for you.

I. Grounding Insights

As a starting point, we must make some critical acknowledgments about this thing we call the public sphere, a place and set of spaces that have been marginalized by the presiding power structures, intentionally and unintentionally. Complacency and confusion among the voting populace have all but replaced creativity and freewill in the quest for political constituencies to shape democracy into a vehicle for very few, select interests.

Our vision for the next evolutionary level of democracy is straightforward: We see a burgeoning polycultural system in which people can live and work on their own terms.

Our certainty around this shift emerges from two primary insights.

First, we connect the breaking down and collapse of familiar institutional elements such as financial and educational systems, monetary policies and political platforms as a welcome and necessary consequence of the systemic entropy found within the current monocultural paradigm. Creative collapse, within an evolutionary framework, is a good thing. It means we are evolving.

Secondly, we know from experience and from history that radical ingenuity — a singular type of creativity capable of world changing effect — only arises when people face down an existential pressure. When commonplace people become, in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a maladjusted, creative minority, there emerges a unique opportunity for them to change the ways they think and act in the world. They challenge and discard their commonplace practices and commonsense ways of dealing with the world.

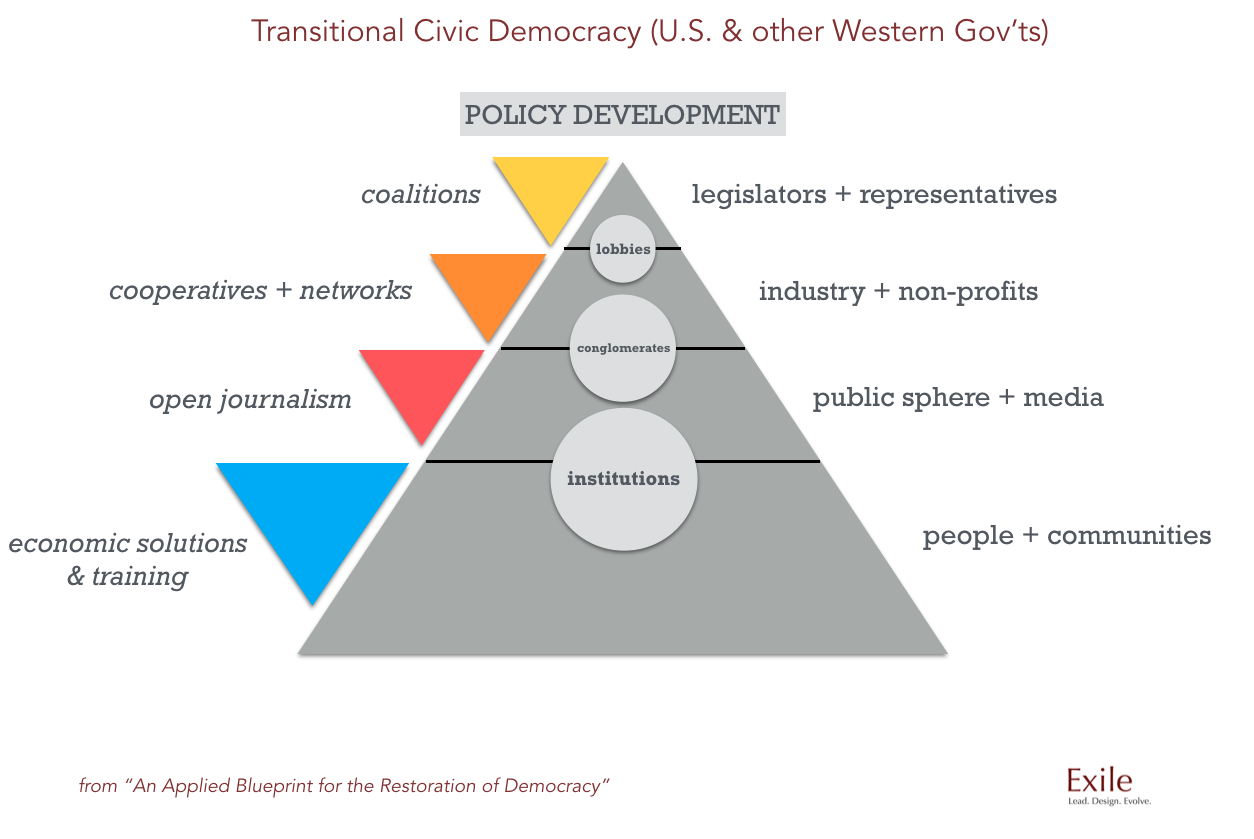

Between legislation, industry, media and community activations, we find tensions between coalitions, networks, journalistic practices, and the ways we train for economic opportunity. Nowadays, most often this comes in the form of suppression — of ideas, of data, of perspective. The most visible forms of these tensions arise in lobbies (AIPAC), corporate conglomerates (News Corp.) and institutions (Tavistock), but these are not truly democratic platforms as we would like to understand them, since they only serve special interests.

Yet, we find that latent pressure — specifically, forms of protest and support found in policy advocacy (MoveOn, CREDO, etc.) — has temporary effects on policy development. The issue here, of course, is that in order to sustain pressure in the form of checks and balances, we have to participate beyond petitions and donations, which are important elements, but in and of themselves still very passive.

Coalitions, networks, along with independent journalism and other non-academic groups that actually generate economic solutions (rather than ideologies) are the critical catalysts in recreating and maintaining democratic checks and balances.

The abiding truth of democracy, and any form of governance for that matter, is that governments are always a direct reflection of the capabilities, skills, power, morality and imagination of the people over whom they preside. Reflexively and conversely, people are the direct representations of governments. The same can be said of corporations and other institutional bodies.

In the U.S., it has been expressed quite clearly by our forefathers: No democracy really exists where the people do not take on the direct responsibilities of guiding policy and keeping powers in check. The failings of this couldn’t be more more obvious with our representative democracy. More proactively, reinventing traditional power structures and cultivating new forms of it are the hallmarks of an evolutionary democracy.

Thus, it can be easily asserted that we do not actually live in a democracy as it were. Call it a republic, a nation state, a corporate totalitarian state, an oligarchy, a polygarchy, a plutocracy, a plutogarchy or whatever you like, but we must do away with the illusion that ‘we the people’ are in control of a runaway train.

What we are in control of, however, is an array of possibilities and future scenarios, that if carefully guided and protected, will yield wondrous results.

II. The Evolution from Monocultures to Polycultures

Money has represented a monocultural paradigm for the last 5000+ years. Single system models for finance, for commerce, for trade and for government have given western civilization a sense of relative stability, often at the expense of cultural and sociopolitical diversity.

The next move in our democracy is in fact a highly intentional evolution, a push towards a polycultural system, or set of systems. The requirement, and interestingly, the result, will be the development of radically different kinds of commitment and civic participation than what we see and experience today. And this is where ‘we’ come in.

The Cartesian, zero sum game worldview has no further merit at a time when what is needed most is sustenance, equitability, diversity and ecological balance. To be perfectly clear about an underlying driver, greed is not good; as well, success and competition don’t have to be driven by greed. Yet, the pursuit of power — in the traditional western sense of it — is almost always an act of greed.

Greed has irrefutably been shown to corrode democratic systems, often demonizing the people and the players who provide economies with sound alternatives. Alternatives are what polyculture requires. Alternatives make democracies pliable, as well as resilient.

Many people struggle to maintain their livelihoods because they don’t have access to opportunities, and more specifically, because they don’t have access to resources — financial, natural, human, intellectual and creative. When people have this kind of access, then they can choose to participate in society in ways that are commensurate with their capacities to learn, their evolving identities, as well as what they see as important to themselves, their families, their friends, as well as the people with whom they work.

These dynamics make for a healthier and more balanced society, to which elements such as racism, sexism, xenophobia, terrorism and extreme nationalism fade away. These elements — which sadly pervade our media and corresponding cultural narratives — comprise, at least in part, what some know to be the Hegelian Dialectic (perceived problem, manufactured reaction, temporary solution). The dialectic has shaped public and geopolitical discourse for far too long. Even worse, ‘we the people’ are caught up in the correlations between social, commercial and political ills, not the causes of them.

It is no great mystery why we have a war machine, and why people suffer despite the fact that there is plenty of land and resources to take care of them. Yet, the ‘why part’ is immaterial comparative to viable alternatives. In other words, when people don’t merely have to survive, they can create possibilities.

The point is to give people the tools to make or create different choices.

III. Seven Critical Areas of Societal Impact

Over roughly 25 years, we have amassed a diverse body of experiences creating grassroots social programs, building and helping finance companies, developing cutting-edge software, consulting to private and publicly held companies from startups to those with billion dollar plus valuations, designing educational and criminal justice reform efforts, and working as part of great teams reimagining the possibilities for media and public policy development.

This set of experiences, while not perfectly laid out and intentional at the time, has shown us a very nice blueprint of the institutional and community-based areas that must be evolved as a thriving, multi-faceted ecosystem in the effort to restore democracy.

We break this blueprint down into the following Seven Areas:

- corporate innovation — building capacities to create economic alternatives that benefit people + planet

- startup development — building companies that solve real economic & ecological problems

- market ecosystems — building alliances that allow companies and organizations to cooperate and compete over value creation

- media reform — developing solutions that elevate thinking & coordinate action beyond op-eds and biased outlets

- educational reform — developing solutions that incite critical discourse & foster creative literacies

- social reform — working amid very challenging socioeconomic conditions to develop alternatives for leadership in poor or disadvantaged communities

- policy reform — developing frameworks that align coordinated action with visions that are equitable between civic and commercial domains

We want to emphasize at this point that we do not present this list as a neat and tidied up Cartesian body of solutions. Instead, the opportunity — and necessity — is to see each discreet element as interwoven, with each area carefully interacting with each other in service to the entire ecosystem.

The beautiful thing is that we do not have to ‘improve’ each space. Instead, all we have to do is recognize what is killing the potential, face up to it, and then build the capability to move on.

Here is where we start to face up to reality:

In corporate innovation spaces we’ve seen that people are attracted to ‘new’ ideas, but are almost always unwilling (or simply unable) to challenge the fundamental nature of presiding business and economic models. Polity, naturally, is also a culprit in the interpersonal development of stakeholders inside and outside of organizations. We have seen this in nearly every kind of company we have worked with, from green, to social impact, to big-time market extraction players.

In startup development spaces we’ve seen that ingenuity exists everywhere, yet leadership is typically weak and the purpose for entrepreneurship is all too often shallow and misguided. What we have learned from all our experience in the startup space is as simple as it is revelatory: Self-mastery as an organizational mandate for leadership development has to be implemented right out of the gate — despite the almost universal practice of focusing only on product, product, product.

With market ecosystems we’ve seen that collaboration is seriously trumped by competition, even though ‘building a bigger pie’ benefits more people. We have built market ecosystems in the Holistics, Materials, Energy and Media spaces; many folks — despite strong intentions and even serious commitments — really struggle to collaborate because their cultural training goes against collaboration. The game, beneath the level of anyone’s awareness, quickly devolves into an ‘all for one, and all for me’ approach.

In media spaces we’ve seen that journalists, ad people and technology folks are mostly stuck in their ways, holding onto broken models that don’t actually enable market growth, or provide more jobs for creative people. In our experience here, fear is the big driver. Folks are terrified of the new, and/or simply cannot understand how market realities and possibilities can be directed to support the creative possibilities of their field. They also suffer from the fact they lack specific training in the art of collaboration, and without such training, collaboration eludes them.

In educational spaces we’ve seen that bureaucratic thinking, fear and self-preservation destroy creative opportunities at the cost of young people’s futures. The big culprit here — predominantly learned from two multi-year reform engagements at the University level as well as large-scale learning software initiatives — is the massive stratification in centers of education between students, teachers, administrators and boards. Everyone sets up their little ivory towers and puts all energy into hoarding the small amount of provisions they see available to them, thus chasing off all the abundance and imagination resident in the ecosystem itself.

Most decidedly, over and over again, we have seen how, at the top, the boards of directors tasked with overseeing the leadership and innovation mandates are highly incapable. University board members rarely achieve their status of board members by being big risk-takers and innovators. In reality, we have seen the opposite almost universally true. They have played it safe in service of becoming deeply respected members of the status quo, and as a consequence, have learned to value risk mitigation over the expansion of one’s moral imagination.

In social working spaces we’ve seen that young people don’t care about ‘big ideas’ — they want to be enrolled in programs and opportunities that they can actually adopt for the long term. Moving the needle from theory to practice here can be extremely difficult, mostly because folks typically are not trained to build theories with disciplined logic, nor are they attuned to apply this logic to historical contexts, and then test scenarios borne out of these theories against reality.

With policy spaces we’ve seen that the same stakeholders sit at the table, time and time again, and that the conversation is circular. This is so obvious as to be laughable. Check out the think tanks, policy boards, and policy reform organizations; look at the experience of the most senior players in those spaces. It is rare indeed to look at such lists and see anything but the ‘elite’ institutions, universities and companies represented in full force.

Now, of course, there are plenty of exceptions in every domain, and to every rule within those domains. What we are describing — along with the assessments therein — are predominant patterns we’ve seen over considerable amounts of exposure and deep interaction that at once inhibit evolutionary growth, and provide the most opportunity going forward.

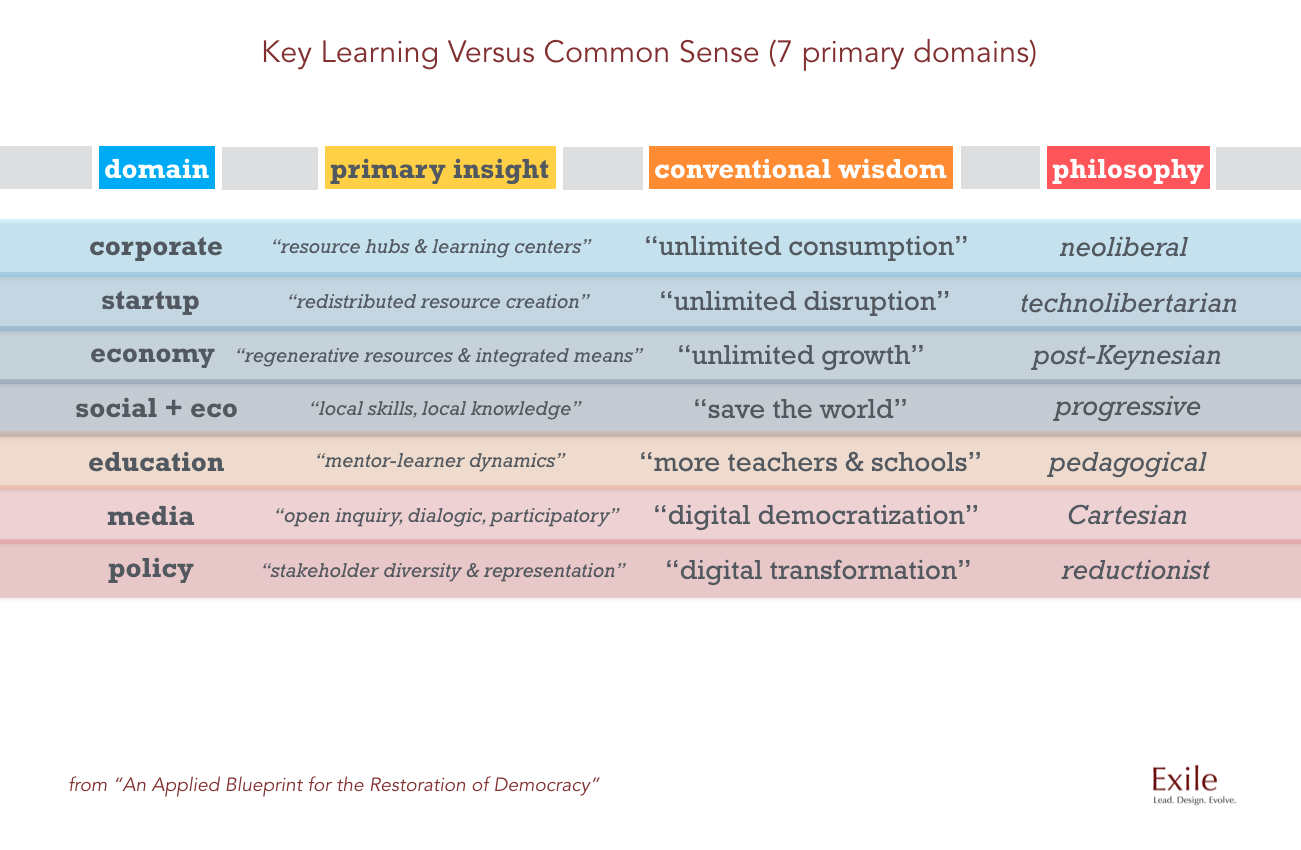

That said, it is apt to contrast what we’ve seen with conventional wisdom. Here is a simple summation of our key learning compared to the memes and narratives dominating the business, market, cultural and sociopolitical landscapes.

Keep in mind that conventional wisdom isn’t ‘wrong’ per se, it’s just that it doesn’t typically ground itself in commitments of action that actually challenge the inherent belief systems. Further, the cognitive and creative distances found within these domains can be wickedly elusive so as to not even allow individuals to see past their own immunity to change, or some version of exceptionalism. In some cases, it brings on dangerous forms of entitlement.

It is useful, at this point, to lay out one example of how all (or most) of these spaces get woven into the creation of an ecosystem that supports and encourages polycultural, democratic reform and civic engagement on multiple societal levels. We will share a few more examples at the end of this writing on projects currently being built, but for now, this is one that is very relevant.

This example encompasses nearly a decade of work from the early 1990s to early 2000s on the west coast of the U.S. imagining, testing and building a new ecosystem — locally and nationally — to engage, support and empower young people, families and communities affected by violence.

Beginning in the mid 80s, urban violence in the United States took on a new element with the introduction of crack cocaine: Youth violence was exploding on a scale that was unprecedented. Systematically, the institutional response measured up, with rare exception, to little more than a catastrophic failure.

Into this environment a small group of us — educators, judges, surgeons, activists, poets, actors, case workers, probation and police officers, prison leaders — came together under the mandate of creating a set of interventions that would actually work on a transformative scale. We were given the space to experiment, to prototype, to take risks, and to use our combined knowledge to create experiences for all the stakeholders in the ecosystem — high risk youth and their families, gang members, and of course, all those in service to helping and serving — that had a root in the expansion of what is called moral imagination.

We were committed to giving these young people and their families a set of experiences that showed them the difference between power and the illusion of power. This core learning was the soil from which everyone then grew a set of skills and practices on which they could build lives outside of the gravitational pull of violence.

The essence of our work — and the many practitioners around the country we worked with, folks like Michael Meade, Carl Upchurch and Jeffrey Canada — was grounded in the principles of ecosystemic design. We trained everyone in core leadership and self-mastery skills. We influenced policy, not by manipulating it, but by providing interpretive frameworks. We built holistic programming grounded in the cultivation of solidarity and strategic alliances that cut across previously unconnected groups of stakeholders in the system. We rooted all our designs in local conditions and we took seriously the mandate that at the core, if we did not create real economic solutions, all of our good work would literally collapse.

Our work exponentially raised not merely the national and community awareness around violence and its impact, but stimulated a body of coherent actions that shaped decision-making, legislation, program development and made educational interventions systemic and holistic. We created a platform for civic engagement and empowerment at multiple levels of society and across institutional domains that was then, and still is today, unprecedented.

IV. Creating New Mental Models + Emergent Forms of Training

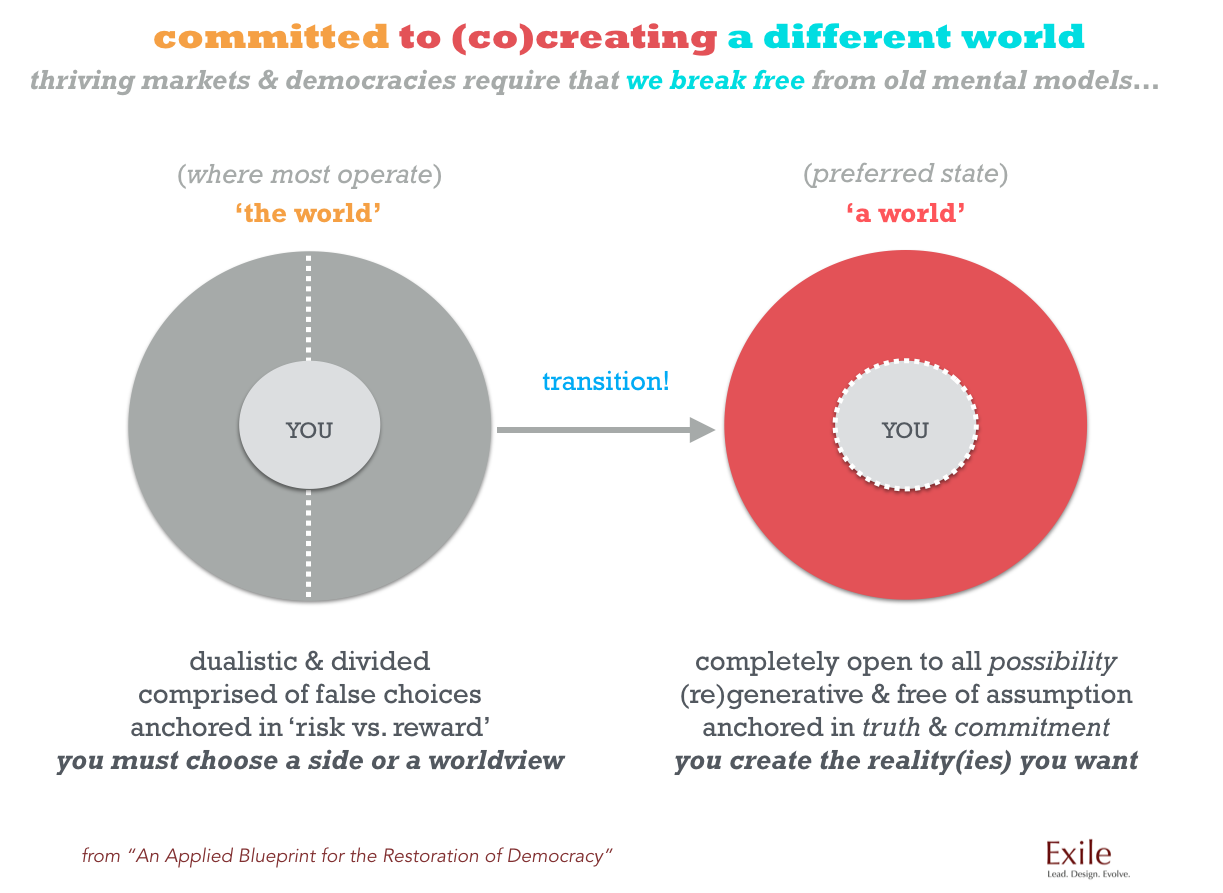

Societal, economic and cultural influence have made it such that people have a very difficult time not only breaking down their own mental models, but once they’ve engaged in developing new ideas, they do not have the strength or the endurance to carry them out and sustain the efforts.

This is one of the fundamental challenges we face in any form of a democracy: Getting to the bottom of one’s belief system, challenging the inner status quo, and liberating oneself from incoherent ways of seeing the world.

This will never happen — contrary to the way a liberal democracy understands the world — from simple awareness, accumulated knowledge and the acquisition of facts. Instead, active participation, experimentation, risk-taking and sacrifice (skin in the game) is the requirement. One must move from being a detached observer never really putting ideas and uncertainties in play, to a person deeply involved in the form of commitments and actions in one’s circumstances.

Therefore, it is critical that we merge civic and commercial interests in ways that incent people to act through levels of participation — participation in positive outcomes, mutual benefits and learning opportunities. And instead of placing the focus mostly on national interests, we place the focus on local interests that contribute to a national and/or a global awareness. The differences, as we’ll explore here, are significant.

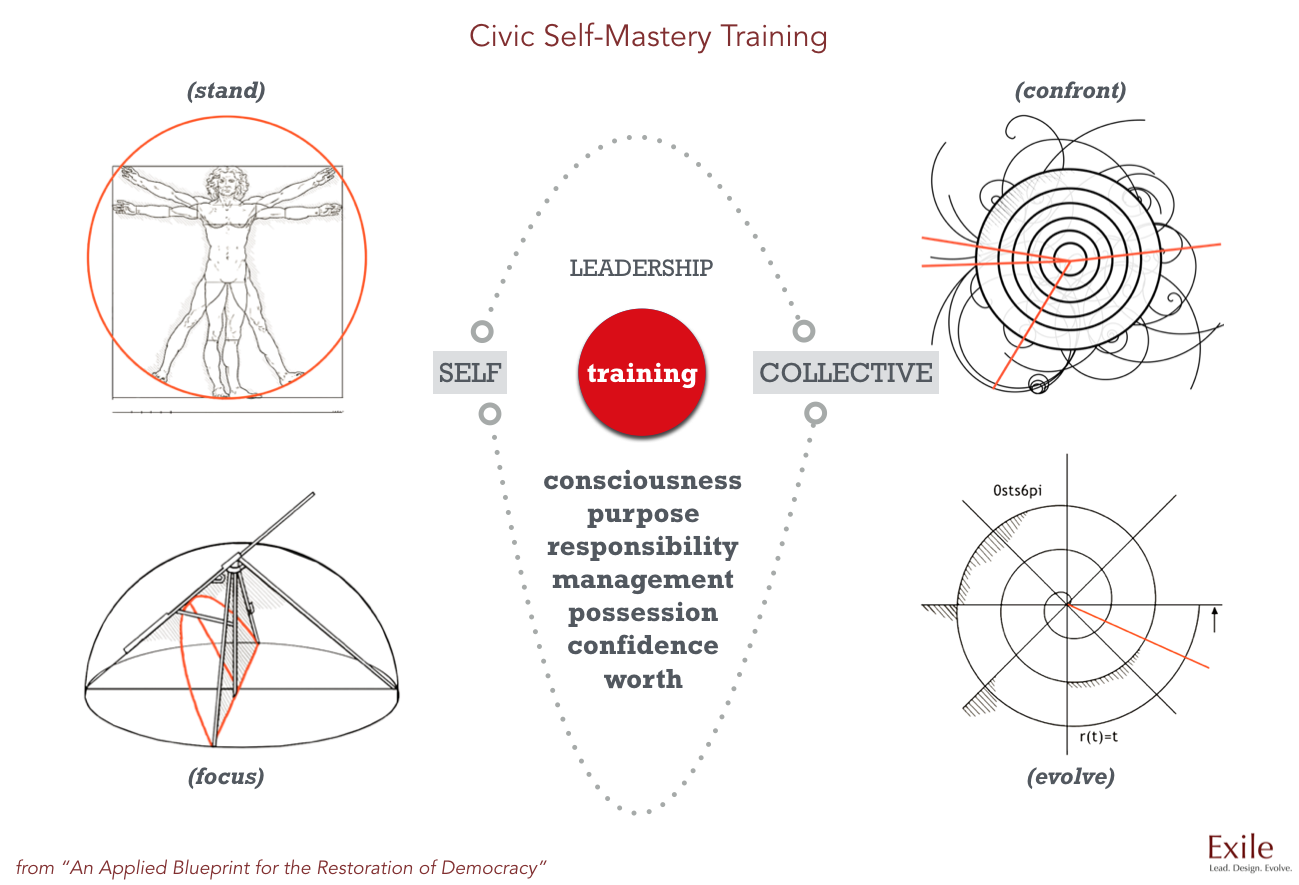

So the first thing we must talk about when we speak of participation is training — a fundamental requirement absent in the liberal worldview.

For the liberal, everyone is entitled to their perspective, opinion and point of view. In fact, it is the job of government to protect the right to every possible perspective, no matter how incoherent and maladaptive. For the conservative, the only people entitled to that perspective are those aligned with the conservative narrative. What unites the liberal and conservative, at the core, is that the speaker is never required to earn the right to speak through the acquisition of actual skill and applied knowledge.

In a civic democracy, participants earn the right to speak by training; to see reality coherently, to build health into the body, to understand that the world works systemically and to privilege local, applied and tested knowledge over abstract theoretical knowledge. In a civic democracy, self-mastery is prized above all other skills and certifications. And this self-mastery, by definition, encompasses the four domains of cognitive, physical, emotional and imaginative or incorporeal (what some might consider ‘spiritual’) skill acquisition.

One important thing to note about the type of training we offer is that it builds up the nervous system of the individual. In countless situations, we’ve witnessed how people participating in leadership, innovation or policy initiatives or even simple brainstorming exercises exhibit deep and profound neurophysiological reactions to new ideas. The ‘no’ switch that people carry around comes out, often subconsciously, when they are presented with ideas or concepts that depart from their worldviews. We have discovered over time and lots of practice that overturning this tendency to say ‘no’ is the most critical element in creating and adopting alternatives to the current neoliberal models.

Digging deeper, the self-mastery training has at its center the cultivation of purpose, responsibility and a special form of confidence borne of an expanded capacity for awareness. Citizens in a civic democracy are given viable, concrete ways to uproot their incoherent belief systems and to let go of their private judgments. They are given the tools to be in a constant state of evolution and committed action. And let us be absolutely clear, we are not describing a utopic, ideal state. Every society trains its people from the time they are born to shape and be shaped by their world in explicit and intentional ways. Nothing, despite appearances, is accidental from the standpoint of societal programming.

We are simply reaffirming the obvious: A liberal democracy trains its citizens to prize their opinions, allegiances, personal beliefs and worldviews as a highest order value. Laws and regulations are designed to ensure that all of these views are protected. A civic democracy takes for granted the maladaptive nature of such a foundational design… Because it has to.

When relatively few have earned the right to speak through committed participation and disciplined training the result is deceptively simple: We find ourselves immersed in an incoherent public sphere, with disempowered citizens and communities, and a pervasive mood of apathy, resignation and anger.

So, we can train to become adaptive to what actually exists in reality, as well as possibilities beyond what we currently see.

When people train for self-mastery they build muscle. They expand their awareness. They become more open and less judgmental. They generate health in their bodies and communities. They understand the distinction between power and the illusion of power as well as between speech that is true and speech that is manipulative and false. Laws, policies and regulations will never give these skills to anybody. However, self-possessed citizens will always create laws, policies and regulations that support human potential and the greater good.

V. The Underpinnings of a Civic Engagement Model

All of the aforementioned has led to us seeing the framework for a different model for democracy — what we are calling a civic engagement model.

In its essence, the civic engagement moment privileges truths, conclusions and solutions that are all generated in the act of doing, testing, failing, prototyping, refining and exploring. All solutions are achieved through concise and coordinated action, in real, physical spaces and collaborative environments. All solutions grow out of local conditions by local actors.

Our current liberal democracy, on the other hand, prizes reflection, objective distance, specialization and the expert from a think tank, a research position or a politician geographically removed from civic or commercial activity who usually has little to no practical wisdom around local conditions and challenges.

A great example of this cognitive distance is represented in various permutations of globalization. Globalization can be a ‘good’ thing or ‘bad’ thing depending on where you sit within the socioeconomic landscape, yet it isn’t really a binary issue, nor is it a black-and-white debate. Notice how policies do not present ‘plus and’ scenarios for globalization.

As one primary example, the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) reflects a short-sighted emphasis on trade and economic growth, favoring corporations over communities, and radically undermining possibilities to reinvent labor or working capacities through new skills development, the enhancement and multimodal protection of intellectual property rights, or the bolstering of redistributive production protocols. In other words, there is nothing innovative about it, and that’s precisely what policies should be doing in the 21st century — providing guidelines for disruptive and/or emergent innovation.

Many geopolitical agendas sit behind these policies, most of them opaque, complex and quite difficult to discern on any reasonable level. But that isn’t the point. The point is that if we want to reestablish and uphold our civic and commercial freedoms, then we need to make serious investments in the outcomes — investments in the form of time, energy, as well as creative, financial and intellectual capital.

VI. Historical Precedents and Background Practices for a Civic Engagement Model

Emerging first in ancient Greece in the form of the polis and later in the Italian Renaissance, and even later in phenomena such as Westphalia, the civic engagement model of democracy has a set of background practices that look very different from the current liberal democracy model(s). These background practices produce a different world that supports and privileges tools and skills that, in totality, are very different from the liberal model.

- The first and perhaps most important distinction between the two models is that a civic democracy begins with the certainty that democracy is the joining together of all to promote the diverse goods of all. In a liberal democracy, this is obfuscated since polycultural traits are difficult to cultivate and civic engagement is virtually absent in any sort of meaningful way. As a result, monocultures are supported — like a two-party system, large corporate hegemony (Facebook, Amazon, Google, Monsanto, etc.), the radicalization of outsider views, and the tendency towards ideology over applied practice;

- A civic engagement model values solutions generated in action over solutions generated in detached reflection;

- A civic engagement model values the constant creation and discovery of regenerative assets (natural and intellectual resources, in particular), along with the ongoing development of polycultural elements over monocultural precepts in the form of collaborative designs, ecosystemic approaches and commercial/commons hybrids;

- A civic engagement model values the primary importance of human training — to act, communicate, participate, engage, and dialogue in a way that contends with opposition, conflict and diverse viewpoints in a generative way as opposed to a binary, argumentative way;

- A civic engagement model values collaboration AND competition; we see the interpolation of the two as the primary litmus for creating necessary tensions leading to diverse forms of value that are durable and those which can be sustained;

- A civic engagement model supports ecosystemic principles whereby diverse — even competing — stakeholders come together to achieve a shared purpose using engagement and participation;

- Civic engagement is a linking of talking and acting, of trying on whole new bodies of experiences and traditions that make problems look different. Of looking at practices that previously we may have ignored. We do more than just hear about other ways of seeing things; we try them out, using our imaginations and higher sensibilities to test them against reality.

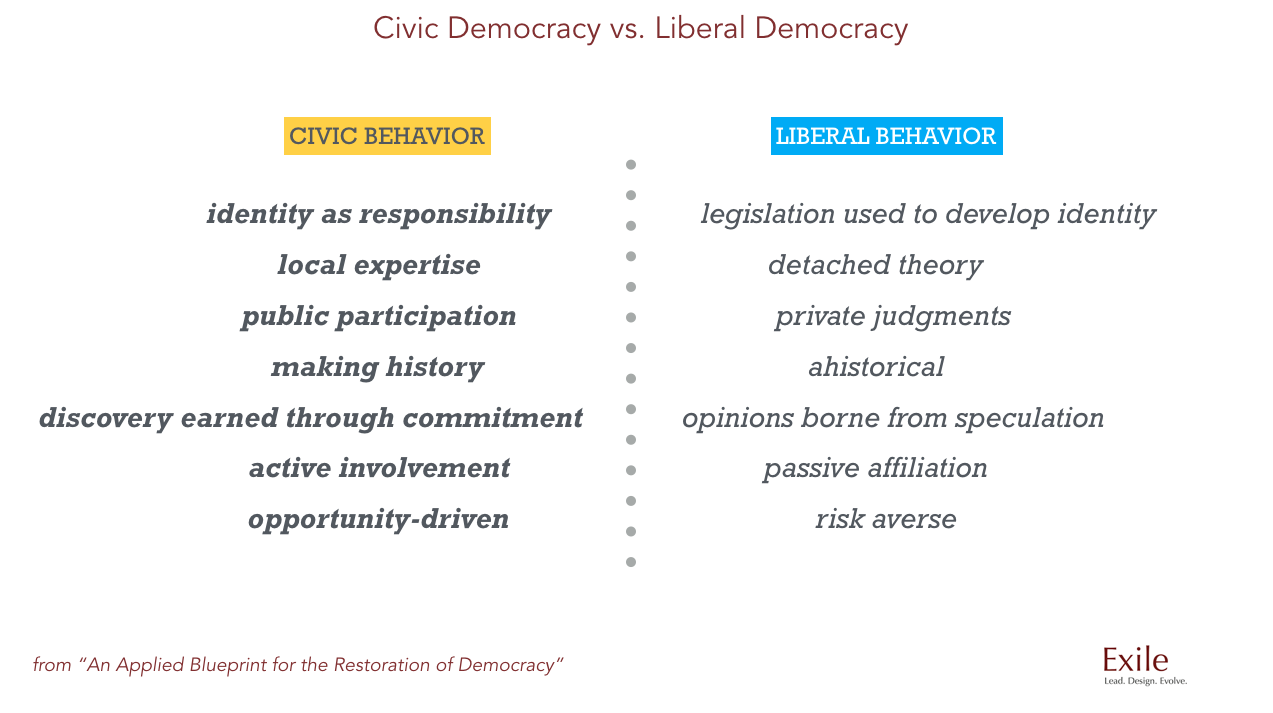

VII. The Fundamental Distinctions Between Liberal & Civic Democracy

The foundational difference between civic and liberal models is that in the civic model, the development of an identity is responsible for laws and regulations, whereas liberals see legislative and regulatory victories as the ground for the development of an identity.

In other words, in the civic model people act, evolve, put skin in the game and understand local conditions in service to change. New laws and regulations flow out of their actions; they are the precedents set by action. In the liberal model, distant officials and so-called experts put laws and regulations in place in order to ensure justice and balance; they are designed to curb certain behaviors and encourage desired outcomes. This is an almost invisible distinction that has massively destructive consequences.

Liberalism promotes widespread resignation and apathy by setting up an expectation that the course of one’s life is ultimately determined in private judgments. In this context, apathy, fear, hope, anxiety and distrust dominate because the conclusions derived in this context are not conclusions one is ready to follow. These are conclusions, truths that are culled from a certain dispassionate reflection — the weighing and sifting of ideas and potential consequences. There is no commitment behind, within or alongside this kind of reflection.

In a civic democracy, people participate in producing history that establishes higher precedents for living, working and coexisting. In a liberal democracy, people are ahistorical. People create a mood of possibility and commitment.

In the liberal democracy of today, instead of participating in the making of history, people participate in the public sphere, which is prized above all other spheres and is fundamentally ahistorical. In the public space politicians, talk show hosts, experts and the general public interact in a way that requires little commitment and no skin in the game, and only presents “rational” views.

Almost without exception, these commentators and experts intentionally detach themselves from the local practices — the context and tacit understanding of a situation — from which all specific issues grow. Thus the conclusions that emanate from this abstraction produce abstract conclusions that will never enlist committed action. The result is that the public sphere gives the impression that everyone has the authority to speak, when the reality is — as basic commonsense tells us — that most do not. And nobody is empowered to take meaningful and coherent action because nothing shared can ever really be applied to one’s life and local circumstances.

In essence, the modern public sphere is separate from presiding power. Presiding power — the kind that currently dominates cultural, economic and political domains — does not listen to the public sphere. As a result, the public sphere undermines the accumulation of practical expertise.

Without a grounding in particular problems, and without the expertise gained from taking risks, the public sphere is reduced to callers on talk shows, and ‘experts’ across a variety of media channels. Every amateur has an opinion that feeds into other amateur opinions. The more serious talk show participants become heroes of the public sphere, the more they resemble folks like Thomas Friedman, who have a view on every issue but do not have to actually take a genuine stand, take substantial risks, and put their money where their mouths are. They, like most in this society, base their actions off a set of abstract, almost invisible principles, instead of learned experience. Thus they are incapable of acting in a way that matches the specificity of each new situation.

So, to reiterate:

For the public sphere to matter, to create genuine participation, it would have to connect to precisely what it resists, which is real human power, (bi)partisanship, risk-taking and the ability to handle local issues with grace and clarity.

VIII. A Policy Framework for Primary Logistics

We cannot offer a static model for how policies can be developed, managed and mitigated, but we can suggest a framework that reestablishes a foundation for substantive change. Because we are not politicos of any sort, this is a fairly simple offering, which therefore contains its own power and relevance. And, we are evolving this framework to set up greater pathways for coordinated action through the various projects and ventures on which we are collaborating.

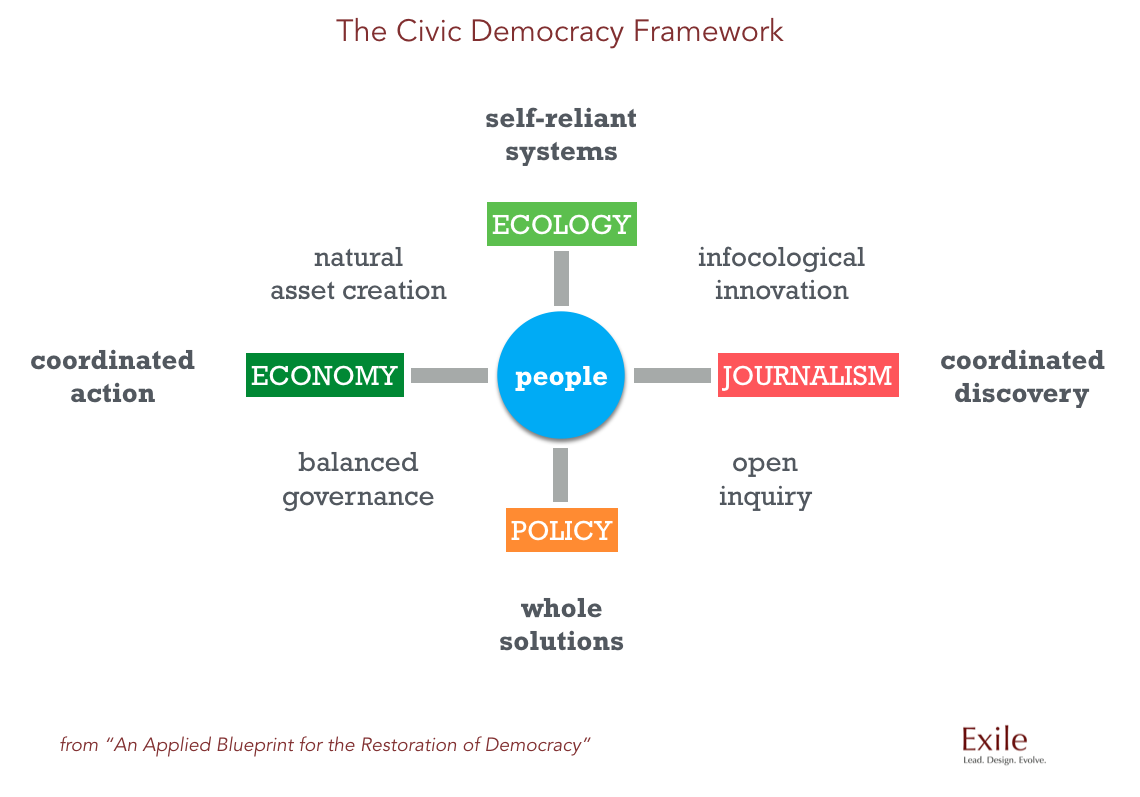

Starting with people, we can see that a human-centered design develops pathways that yield swift and highly effective ecological, economic, journalistic and policy-oriented results. At the intersections, we find the creation of new assets (natural resources and human innovations), governance that is both self-informed and collectively responsible, new forms of open inquiry (new questions, variant explorations), and innovations that improve our infocologies (the ways information takes shape and spreads), specifically in the media and educational domains.

What we see as the primary operators in this construct are self-reliant systems in the form of ecologies that can sustain themselves, as well as those which regenerate resources and consistently improve upon local conditions; coordinated discoveries that fuel interest and investments in all that we don’t know that we don’t know (the unknown unknowns); whole solutions to systemic challenges that are mostly proactive rather than reactive; and coordinated actions that are powerful, decisive, transparent and which reflexively bridge knowledge gaps between the public and private sectors.

It is worth noting that technology is an amazing catalyst in all of this. But make no mistake about it: An atomic, polycultural and irreducable social design — specific to the development of local communities and variations of them — is what critically makes the civic engagement engine work. Imagine every city, every community, every rural center, every town hall replete with its own customized version of a civic engagement model, based on ecological variants, predominant socioeconomic needs, deeply embedded journalistic practices, and policies that actually create opportunity for anyone who chooses to participate.

If technology in many unique ways enhances and accelerates the associative experiences and learning, then great. There are plenty of open source tools and independent platforms available, and many others emerging. In truth, civic engagement will never rely on Facebook pages, Google searches, or Twitter feeds for human interaction and community-centric creativity. Those capacities and emerging literacies exist in the minds, imaginations and hearts of people. Literacies of the imagination, as we like to call them, can only be fostered through deepened interactions in physical spaces and within places where nature can bring human beings back to their true essence.

IX. More Real-World Examples of Coordinated Action

Societal, economic, geopolitical and environmental pressures abound. As we have seen in many instances over the years, the typical human response is to contract under such pressure, rather than expand through it. This is why the training we have described is so vitally important — only sound minds, healthy bodies and attuned powers of spirit and imagination can take on the challenges of a world in great transition.

We have witnessed firsthand the deleterious effects of not training and not expanding the capabilities for change and adaptation: From progressive movements quickly losing energy and intellectual puissance, to misguided campaigns to help indigenous communities that result in mere calamity, to liberal efforts which threw large sums of money at problems without reframing them, or even considering their origins.

Alas, civic engagement is the quintessential form of distributive leadership. Distributive leadership embodies all the attributes of real participation in policy development, and makes implicit a self-responsibility to express learning as the means for evolving the checks and balances of a democracy, no matter what socioeconomic conditions exist, and no matter how complex the sociocultural dynamics may be.

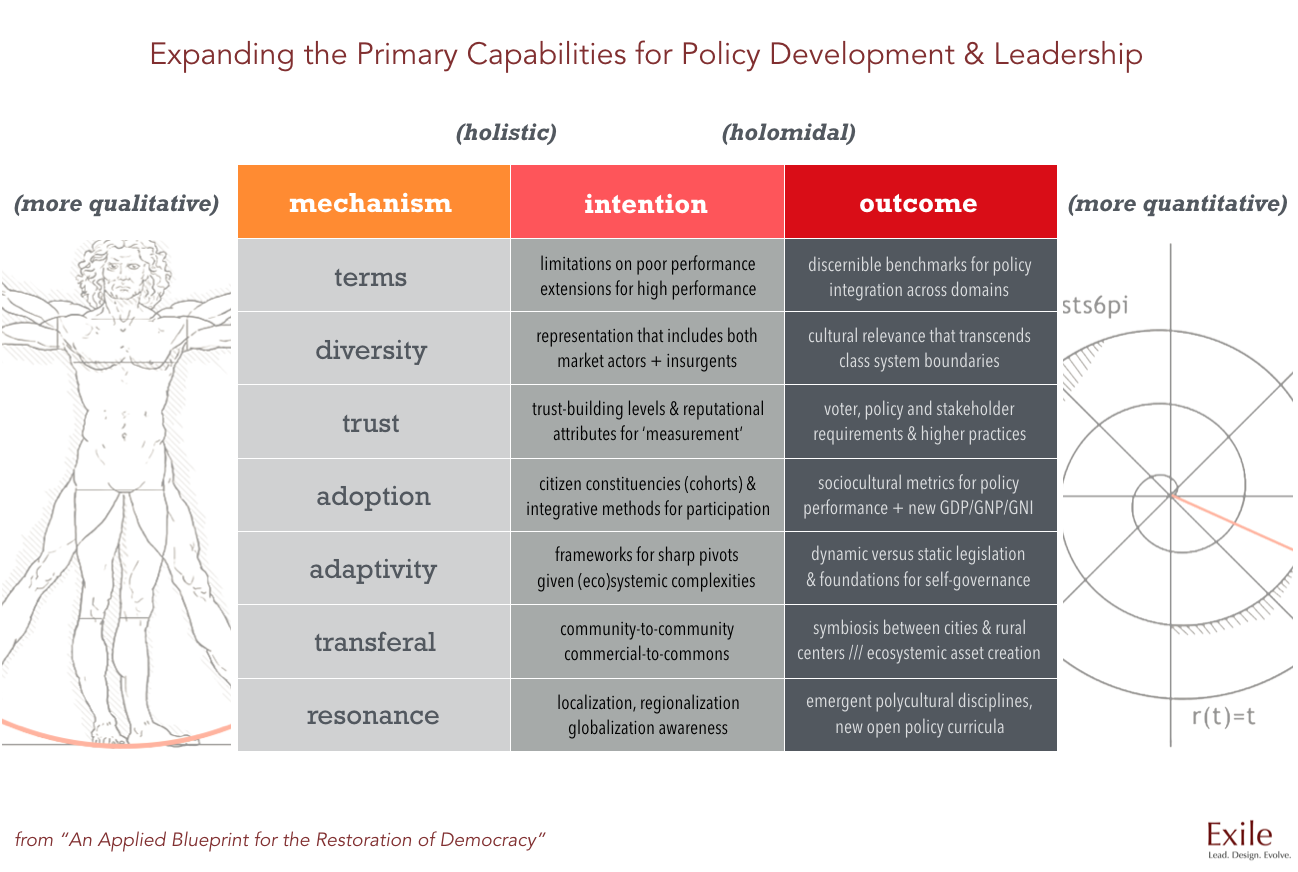

Here we can see how expanding our primary capabilities through pressure creates a harmony between mechanistic political drivers, intentionality and discernible outcomes.

We mentioned atop this piece that ‘fixing’ the current system is futile. To be more specific about that point, what we see happening in this transitional approach is accosting and improving upon certain elements in the current system for the (co)creation of a new one.

So to briefly summarize, things like term limits, voting reform and policy thresholds would find new life within localized contingencies, which in turn would affect how the system works at the national or federal level. An example of this is how the states-rights movement in America is forcing the hand of legislators on Capitol Hill. It’s a slower, more painful process no doubt (and not well documented across mainstream media channels), but an effort that at the very least reveals how we can evolve political discourse from the ‘bottom up’.

One initiative worth mentioning that comprises all the mechanics of terms, diversity, trust, adoption, adaptivity, transferal and resonance is a large alternative energy project we are co-designing and for which we are raising funds in North America, with significant implications worldwide.

The project is the vision of several market players in regions profoundly (negatively) affected by fossil fuel production and consumption, who see a new opportunity in a thriving market ecosystem with a new kind of alternative energy infrastructure — replete with upleveled democratic processes — as the linchpin for sustained business and socioeconomic growth. We are developing a core energy product that is revolutionary and one that will irrevocably change every supply chain on the planet.

Yet, what we know to be most critical are the ‘fringe efforts’; specifically, how we are integrating economic innovations with indigenous communities (First Nations coalitions) — developing customized programs and solutions with them that provide better housing, new types of schools and learning foundations (representing local, tribal customs and values), better agricultural practices, better energy practices, and better policy practices with ‘outside’ groups, among many other outcomes. We will also provide Commons and hybrid versions of the intellectual property that is developed such that these communities can create their own market vehicles, and share the results with other communities, not to mention provide government agencies with critical data to inform future policy development.

We must emphasize that these community efforts are incredibly important in the redesign of the market ecosystem, and reflect the true nature of civic engagement: designing with the communities, not designing for them. As mentioned throughout this writing, local knowledge and local actors are the necessary participants in a civic democracy.

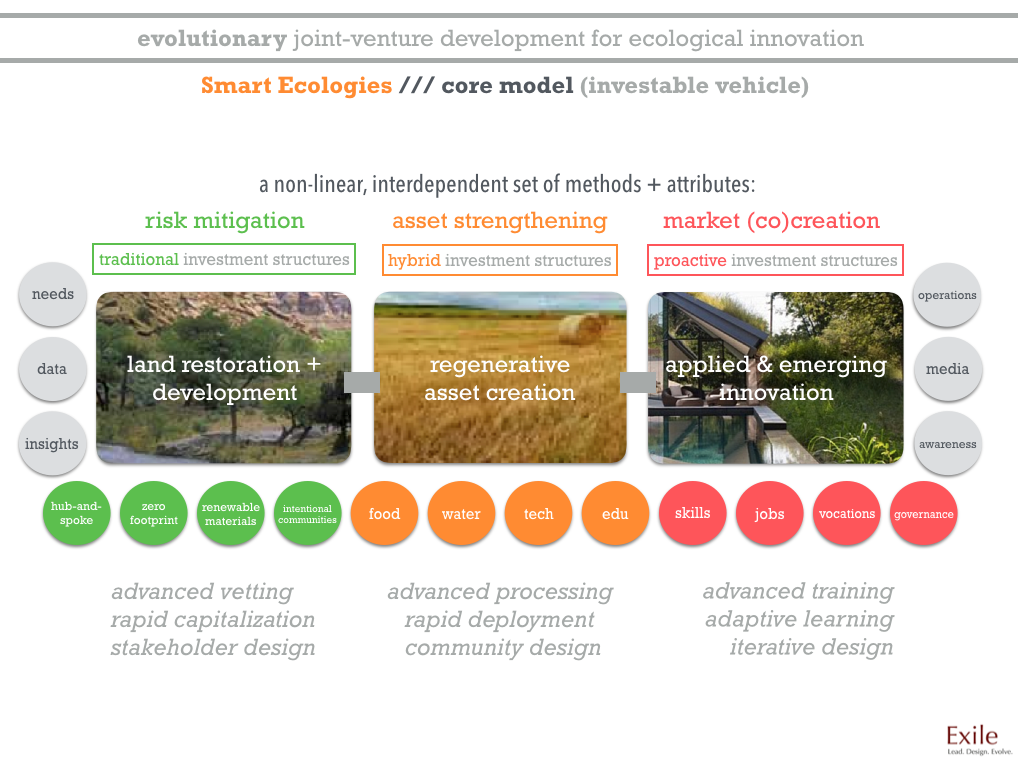

Our Smart Ecologies platform is the ‘wrapper’ for the work we are doing currently in select parts of the world. This platform focuses on several key elements tied directly to civic engagement:

- creating new, regenerative assets & asset classes (resource pools)

- enabling the development of new, adaptive vocational skills

- giving entrepreneurs an array of options to capitalize & iterate their ideas

- giving corporate & institutional stakeholders new opportunities to innovate at sustained levels of ‘growth’ & ‘scale’

- offering companies & co-operatives of various profile types alternative finance & governance models

- creating restorative & adaptive infrastructures (food, water, energy, media, education, etc.)

- helping people develop sustained relationships with their inner power & higher purpose

We are also in development on a new journalistic and media platform that is based upon open inquiry, and incites people to connect through coordinated action around specific local needs. The platform will provide alternatives for journalists and publishers to monetize their impact, free from ad models and fixed algorithms that commodify the quality of information, as well as the processes of due diligence that actually make what we read and understand critically resonant.

We will continue to co-design and implement self-mastery programs inside of institutions and corporations around the world, until this kind of training is more pervasive and no longer requires a direct hand in its proliferation.

Within institutional and corporate domains, we are also in the beginning stages of advancing what we call economic design. What this means is that companies are now tasked with the responsibility of creating assets they may not own outright in order to build market ecosystems and remain relevant as ‘brands’. These assets can be technologies (apps), utilities (energy solutions) or other informational and production offerings (partner supply chain improvements). It also means that they must help create solutions for the very environments in which they operate, and not just through endowments, non-profit entities or sustainability teams that are in reality separate from company operations.

We are currently in talks with several groups on the policy development front. Our main thrust here is to integrate emergent design principles into the mix along with deep training practices and a diversity of unique stakeholder perspectives.

We will, of course, share more as we implement and grow these efforts.

X. An Open Conclusion

We wrote this piece for two primary reasons.

The first: As a vehicle to help ourselves make sense of our own circumstances. Reality, at this moment in history, is more than a little confounding. The rigor required to bring our insights into some manner of coherence helps us to see more clearly, while we continue to do the applied work on the ground and in the trenches, so to speak.

The second was to create a bat-signal of sorts. We know there are people out in the underexposed areas of the planet actively engaged in the important work of stewarding in a new blueprint for society that is decidedly and radically supportive of human beings, local communities and ecological sanity. We see our applied blueprint for the restoration of democracy as an axiomatic initial step around which much good can be built.

Our call-to-action is designed to be both a challenge and an invitation. We aim to challenge the prevalent commonsense change strategies (create a think tank, build an institute, host a conference, protest a wrong, enact corporate sustainability policies, fight for justice, etc.); they do not scale and they never will. In that vein, we would love to see an entire generation of progressive actors free themselves from their tired and traditional approaches to change. We would also, of course, love to see the permanent breakdown of the absurd boundary between the ‘right’ and the ‘left’.

To all of the experienced, well-resourced doers out there: We invite you to share your challenges and get messy playing in our world for a bit. Our promise is that it will be a lot more fun than pulling boulders up the hill within the liberal democratic framework, and it will unleash new elements of imagination and commitment for you as well as for others in your networks.

The seduction, at this moment in history, is to fall for one of two polarities. The first is the consoling illusion that with a bit of tinkering here or there society will correct itself — the incremental strategy. The second is a confused, and deeply emotional, contracted reaction to the goings-on in our world that results in a dizzying mix of anger, resignation, apathy and despair — the “everyone outside of my comrade circle is stupid” strategy.

Instead, we are proposing a third alternative. Let’s collectively demonstrate the courage that facing up to reality requires: This experiment in democracy demands our disciplined participation and stewardship. Nobody is stupid, nothing is inevitable, and everything made of human hand and ideas is forever open to a redesign.

It is time to accept, and bring to life in the present moment, our inheritance as active participants in history.

We welcome your commitment and participation.

RELATED PIECES:

(an incredibly deft analysis of the Deep State — our current governmental reality — written by 28-year congressional veteran, Mike Lofgren…)

(an article on the Deep State through the lens of the current Trump administration, written by our colleague and partner in INSURGE Intelligence, Dr. Nafeez Ahmed…)

(great perspective from 1997 on the ‘democratic moment’, and of particular note, the realities of capitalism’s impact on society + policy formation…)

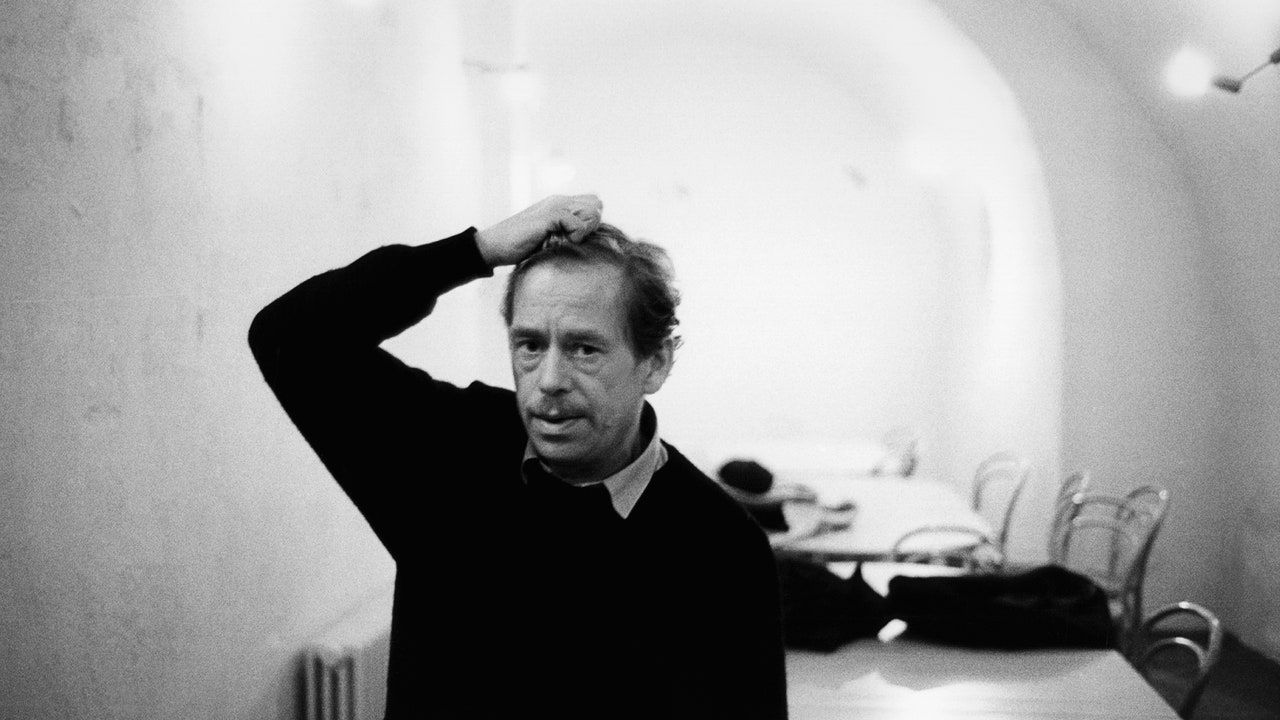

(an article on Václav Havel’s approach to active dissidence…)

(an article on Universal Basic Income which pulls in the concepts of civic participation…)

(Mondragon — one of best examples of ‘good capitalism’ and integrated democratic processes anywhere in the world…)

Postscript: We will be following up with a piece on defense and military strategy, and how those elements can be woven seamlessly into a civic engagement model.